Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the valleys of central Mexico, where ancient pyramids reach for the sky and weathered stone warriors stand eternal guard, lies the enigma of the Toltecs. This long-vanished civilization, flourishing over a millennium ago, has left behind ruins that whisper of grandeur but reveal little of the inner world of this long-gone people. Archaeologists sift through the dust of Tula, piecing together fragments of a society renowned for its artistry, warfare, and influence on later empires like the Aztecs. Yet, beyond these tangible remnants, the Toltecs remain a mystery to people of the modern age. They left behind no written records, no deciphered texts, just vague echoes in myths and glyphs. It’s this very obscurity that has made the Toltecs ripe for reinvention. Since the 1960s, a vibrant movement has emerged, cloaking itself in the mantle of “Toltec spirituality.” Workshops, books, and retreats promise access to ancient wisdom: techniques for personal mastery, dream control, and harmonious living drawn from supposed modern-day Toltec shamans. Proponents describe the Toltecs not as historical figures but as enlightened beings, “artists of the spirit” who mastered reality itself. This philosophy has captivated millions, blending seamlessly into the broader New Age tapestry of self-help and mysticism. But beneath the allure lies a troubling question: Is this genuine heritage, or a modern fabrication filling the voids of history with fantasy? In this exploration, we’ll delve into the phenomenon of fake Toltec spirituality, tracing its roots, key architects, and the criticisms it faces, all while honoring the real mysteries of Mexico’s past.

In the valleys of central Mexico, where ancient pyramids reach for the sky and weathered stone warriors stand eternal guard, lies the enigma of the Toltecs. This long-vanished civilization, flourishing over a millennium ago, has left behind ruins that whisper of grandeur but reveal little of the inner world of this long-gone people. Archaeologists sift through the dust of Tula, piecing together fragments of a society renowned for its artistry, warfare, and influence on later empires like the Aztecs. Yet, beyond these tangible remnants, the Toltecs remain a mystery to people of the modern age. They left behind no written records, no deciphered texts, just vague echoes in myths and glyphs. It’s this very obscurity that has made the Toltecs ripe for reinvention. Since the 1960s, a vibrant movement has emerged, cloaking itself in the mantle of “Toltec spirituality.” Workshops, books, and retreats promise access to ancient wisdom: techniques for personal mastery, dream control, and harmonious living drawn from supposed modern-day Toltec shamans. Proponents describe the Toltecs not as historical figures but as enlightened beings, “artists of the spirit” who mastered reality itself. This philosophy has captivated millions, blending seamlessly into the broader New Age tapestry of self-help and mysticism. But beneath the allure lies a troubling question: Is this genuine heritage, or a modern fabrication filling the voids of history with fantasy? In this exploration, we’ll delve into the phenomenon of fake Toltec spirituality, tracing its roots, key architects, and the criticisms it faces, all while honoring the real mysteries of Mexico’s past.

To understand the modern myth, we must first ground ourselves in what little we know of the actual Toltecs. Emerging around 900 AD in the wake of Teotihuacan’s collapse, the Toltecs established their capital at Tula, a site northwest of modern Mexico City. Spanning a little under 7 square miles, Tula was a hub of innovation, boasting monumental architecture like the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl, adorned with feathered serpent motifs, and the iconic Atlantean figures, the easily recognizable 13-foot-tall massive stone warriors supporting temple roofs. These structures suggest a society skilled in metallurgy, pottery, and urban planning, with trade networks extending to the Maya in the south and perhaps even what is now known as the American Southwest. The Toltecs’ legacy endured through the Aztecs, who arrived centuries later and idolized them as precursors. In Aztec lore, the Toltecs were “tolteca,” meaning “artisans” or “builders,” credited with inventing crafts, calendars, and even the ball game. Myths portrayed Tula as a paradise of jade and gold, ruled by wise kings like Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, a semi-divine figure who blended human and  god. But these stories were Aztec inventions, romanticizing the Toltecs to legitimize their own empire. Archaeologists confirm Tula’s prosperity but note its decline around 1150 AD, likely due to drought, invasion, or internal strife; evidenced by burned palaces and scattered remains. Crucially, no direct Toltec writings survive. Unlike the Maya with their hieroglyphs or the Aztecs with pictographic codices, the Toltecs left only symbolic art: stone carvings of eagles devouring hearts, jaguar knights, and ritual scenes. Interpretations of these images vary. Were these depictions of warfare, religion, or cosmology? Scholars like Alfredo López Austin argue the Toltecs shared Mesoamerican beliefs in a cyclical universe, blood sacrifice, and deities like Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl, but without texts, it’s all just speculation. This historical vacuum—a blank slate of ruins and legends—has proven irresistible to those seeking so-called “lost knowledge.” In the absence of facts, imagination thrives, paving the way for the New Age reinterpretation.

god. But these stories were Aztec inventions, romanticizing the Toltecs to legitimize their own empire. Archaeologists confirm Tula’s prosperity but note its decline around 1150 AD, likely due to drought, invasion, or internal strife; evidenced by burned palaces and scattered remains. Crucially, no direct Toltec writings survive. Unlike the Maya with their hieroglyphs or the Aztecs with pictographic codices, the Toltecs left only symbolic art: stone carvings of eagles devouring hearts, jaguar knights, and ritual scenes. Interpretations of these images vary. Were these depictions of warfare, religion, or cosmology? Scholars like Alfredo López Austin argue the Toltecs shared Mesoamerican beliefs in a cyclical universe, blood sacrifice, and deities like Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl, but without texts, it’s all just speculation. This historical vacuum—a blank slate of ruins and legends—has proven irresistible to those seeking so-called “lost knowledge.” In the absence of facts, imagination thrives, paving the way for the New Age reinterpretation.

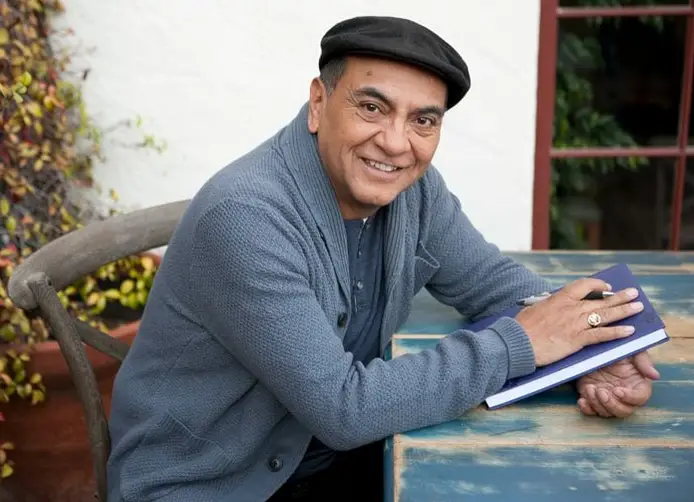

The 1960s saw a cultural earthquake in the West: the rise of the counterculture, psychedelics, and a hunger for alternative spiritualities. As disillusioned seekers turned from organized religion, they looked eastward to yoga and Zen, or southward to indigenous traditions. Mexico, with its rich pre-Columbian heritage, became a focal point. Enter Carlos Castaneda, the enigmatic Peruvian anthropologist whose books are credited with igniting the Toltec revival. Castaneda’s 1968 debut, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, chronicled the author’s alleged apprenticeship under a Yaqui shaman in Sonora. Describing hallucinogenic journeys with peyote and datura, the book blended ethnography with adventure, selling over 28 million copies worldwide. But Castaneda soon pivoted to “Toltec” themes, claiming his mentor, Don Juan Matus, was heir to an ancient lineage of Toltec “warriors” and “seers.” In later works like Journey to Ixtlan written in 1972 and his 1974 book Tales of Power, he outlined a philosophy of “seeing”—perceiving reality beyond illusions—and “stalking,” a metaphorical hunt for personal power. By the 1990s, Castaneda formalized this into “Tensegrity,” a system of movements and poses purportedly derived from 25 generations of Toltec shamans. Workshops promised participants could “recapitulate” past lives, control dreams, and achieve “impeccability.” His inner circle, dubbed “the witches,” included mostly White North American women who adopted new identities and lived in seclusion, fueling rumors of a cult. Castaneda’s influence extended beyond books; he inspired films, music, and a generation of spiritual tourists flocking to Mexico for “authentic” Toltec experiences. Yet, even as his empire grew, cracks appeared. Investigations revealed inconsistencies: Don Juan’s whereabouts didn’t  match Yaqui territories, rituals were borrowed from varying sources, timelines defied logic, Yaquis were not related to the ancient Toltec civilization, and modern Toltec “shamans” were really mestizo Mexicans with no connection to modern or ancient tribal cultures. Critics like Richard de Mille accused Castaneda of fabrication, labeling his work “anthropofiction.” After his 1998 death, scandals erupted: disappearances among followers, allegations of abuse, and admissions that much was invented. Despite this, Castaneda’s Toltec myth persisted, morphing into a self-help staple. Enter Don Miguel Ruiz, a more palatable successor. A Mexican surgeon turned author, Ruiz burst onto the scene with The Four Agreements which debuted in 1997. This slim volume distilled “Toltec wisdom” into four principles: Be impeccable with your word; Don’t take anything personally; Don’t make assumptions; Always do your best. Marketed as ancient shamanic knowledge from his indigenous grandmother, the book resonated in Oprah-endorsed circles, selling over 10 million copies and spawning sequels, apps, and seminars. Ruiz portrayed Toltecs as “masters of self,” artists who shaped reality through intent, free from “domestication” by society. His teachings emphasized love, forgiveness, and dream mastery which echoed Castaneda but seemed softer and more accessible. Followers could attend retreats in the ruined city of Teotihuacan, blending Toltec lore with pyramid energy work. Ruiz’s son, Don Jose Ruiz, continued the legacy with books like The Fifth Agreement, which expanded the family’s supposed Toltec-based brand. This movement didn’t stop at books. Online platforms buzz with “Toltec shamans” offering virtual sessions: guided meditations to “reclaim your power,” oracle cards inspired by Tula glyphs, and even “Toltec astrology” tying personal growth to Mesoamerican calendars. Organizations like the Toltec Center of Creative Relationships promote community-building through these principles, while apps deliver daily affirmations. What began as countercultural exploration has become a lucrative industry, with retreats costing thousands and books generating millions.

match Yaqui territories, rituals were borrowed from varying sources, timelines defied logic, Yaquis were not related to the ancient Toltec civilization, and modern Toltec “shamans” were really mestizo Mexicans with no connection to modern or ancient tribal cultures. Critics like Richard de Mille accused Castaneda of fabrication, labeling his work “anthropofiction.” After his 1998 death, scandals erupted: disappearances among followers, allegations of abuse, and admissions that much was invented. Despite this, Castaneda’s Toltec myth persisted, morphing into a self-help staple. Enter Don Miguel Ruiz, a more palatable successor. A Mexican surgeon turned author, Ruiz burst onto the scene with The Four Agreements which debuted in 1997. This slim volume distilled “Toltec wisdom” into four principles: Be impeccable with your word; Don’t take anything personally; Don’t make assumptions; Always do your best. Marketed as ancient shamanic knowledge from his indigenous grandmother, the book resonated in Oprah-endorsed circles, selling over 10 million copies and spawning sequels, apps, and seminars. Ruiz portrayed Toltecs as “masters of self,” artists who shaped reality through intent, free from “domestication” by society. His teachings emphasized love, forgiveness, and dream mastery which echoed Castaneda but seemed softer and more accessible. Followers could attend retreats in the ruined city of Teotihuacan, blending Toltec lore with pyramid energy work. Ruiz’s son, Don Jose Ruiz, continued the legacy with books like The Fifth Agreement, which expanded the family’s supposed Toltec-based brand. This movement didn’t stop at books. Online platforms buzz with “Toltec shamans” offering virtual sessions: guided meditations to “reclaim your power,” oracle cards inspired by Tula glyphs, and even “Toltec astrology” tying personal growth to Mesoamerican calendars. Organizations like the Toltec Center of Creative Relationships promote community-building through these principles, while apps deliver daily affirmations. What began as countercultural exploration has become a lucrative industry, with retreats costing thousands and books generating millions.

For all its appeal, Toltec spirituality faces sharp rebuke as a “fake” construct, a blend of cultural appropriation, pseudohistory, and profit-driven pseudoscience. At its core is the issue of authenticity: With no surviving Toltec texts, how can modern teachers claim direct descent? Indigenous scholars argue it’s impossible. The Toltecs weren’t a unified “spiritual” people but a warrior elite. Their rituals likely involved human sacrifice and conquest, far from the peaceful enlightenment peddled today. This reinvention exemplifies “plastic shamanism,” a term coined by Native activists for non-indigenous or loosely connected individuals commodifying sacred practices. Castaneda, a Peruvian immigrant to the U.S., had no verifiable ties to Yaqui or Toltec lineages; Ruiz, while Mexican, draws from a generalized “shamanic” heritage that critics say dilutes real Native traditions. Indigenous groups decry this as theft. Supposed Toltec shamans are stripping rituals of context and selling  them to affluent outsiders. Many of these outsiders are American or Western European liberals wishing to assuage their “White Guilt” by virtue signaling to their friends about how they were progressive enough to take part in and support indigenous spirituality. Broader New Age pitfalls amplify the problem. The movement’s emphasis on “personal reality” can foster a self-centered focus, where believers ignore systemic issues like poverty or colonialism in favor of “vibrational” fixes. These supposed Toltec teachings often promote “agreements” that sound empowering but risk victim-blaming: If life sucks, it’s because you assumed wrong. This ties into “spiritual bypass,” a psychological term for using mysticism to avoid doing real emotional work. Fraud allegations abound. Castaneda’s group was linked to exploitation, with followers signing over assets and enduring intense psychological control. Ruiz’s empire, while less controversial, faces accusations of being a repackaging or blend of several different philosophies including Stoicism, Buddhism, and even old Dale Carnegie motivational tapes, served up with a Toltec veneer for exotic appeal. Workshops promise transformation but deliver feel-good platitudes, leaving participants hooked on more courses or “coaching” sessions. Cultural erasure is another concern. By mythologizing Toltecs as universal sages, the movement overlooks Mexico’s living indigenous cultures. Real shamans in communities like the Huichol or Maya practice authentic age-old traditions tied to land and ancestors, not global self-help and individual empowerment. New Age tourism floods sacred sites, disrupting locals while profiting outsiders. Social media amplifies this: Hashtags like #ToltecWisdom flood Instagram with filtered pyramids and quotes, often from non-Mexican influencers with no cultural connection. Politically, Toltec spirituality intersects with fringe ideas. Some blend it with conspiracy theories—claiming Toltecs knew about aliens or Atlantis—or transhumanism,

them to affluent outsiders. Many of these outsiders are American or Western European liberals wishing to assuage their “White Guilt” by virtue signaling to their friends about how they were progressive enough to take part in and support indigenous spirituality. Broader New Age pitfalls amplify the problem. The movement’s emphasis on “personal reality” can foster a self-centered focus, where believers ignore systemic issues like poverty or colonialism in favor of “vibrational” fixes. These supposed Toltec teachings often promote “agreements” that sound empowering but risk victim-blaming: If life sucks, it’s because you assumed wrong. This ties into “spiritual bypass,” a psychological term for using mysticism to avoid doing real emotional work. Fraud allegations abound. Castaneda’s group was linked to exploitation, with followers signing over assets and enduring intense psychological control. Ruiz’s empire, while less controversial, faces accusations of being a repackaging or blend of several different philosophies including Stoicism, Buddhism, and even old Dale Carnegie motivational tapes, served up with a Toltec veneer for exotic appeal. Workshops promise transformation but deliver feel-good platitudes, leaving participants hooked on more courses or “coaching” sessions. Cultural erasure is another concern. By mythologizing Toltecs as universal sages, the movement overlooks Mexico’s living indigenous cultures. Real shamans in communities like the Huichol or Maya practice authentic age-old traditions tied to land and ancestors, not global self-help and individual empowerment. New Age tourism floods sacred sites, disrupting locals while profiting outsiders. Social media amplifies this: Hashtags like #ToltecWisdom flood Instagram with filtered pyramids and quotes, often from non-Mexican influencers with no cultural connection. Politically, Toltec spirituality intersects with fringe ideas. Some blend it with conspiracy theories—claiming Toltecs knew about aliens or Atlantis—or transhumanism,  where “dreaming” evolves into virtual-reality escapes. This can veer into far-right territory, romanticizing “warrior” archetypes in ways that echo so-called toxic masculinity. Yet, defenders argue value in the myth. Even if invented, these teachings help people navigate modern stress, fostering mindfulness and ethics. Ruiz fans credit the agreements with saving marriages while Castaneda readers find solace in “seeing” illusions. Is it harmful if it heals?

where “dreaming” evolves into virtual-reality escapes. This can veer into far-right territory, romanticizing “warrior” archetypes in ways that echo so-called toxic masculinity. Yet, defenders argue value in the myth. Even if invented, these teachings help people navigate modern stress, fostering mindfulness and ethics. Ruiz fans credit the agreements with saving marriages while Castaneda readers find solace in “seeing” illusions. Is it harmful if it heals?

As we sift through the ruins of fact and fiction, the Toltec phenomenon reveals deeper truths about human longing. In an era of uncertainty, the allure of ancient wisdom is potent, a spiritual ointment for souls adrift in technology and turmoil. Mexico’s pre-Columbian past, with its cosmic dramas and heroic figures, offers a canvas for projection. But this comes at a cost: diluting history, marginalizing indigenous voices, and perpetuating colonial patterns under spiritual guises. For those prone to wonder, the real Toltec mystery endures, not in made-up mantras, but in the stones of Tula and the unanswered questions of archaeology. Perhaps the greatest “Toltec wisdom” is humility: acknowledging what we don’t know, respecting the past without claiming it. As seekers, we might do well to explore with curiosity, not commodification. In the end, whether New Age invention or fragmented legacy, the quest for Toltec spirituality mirrors our era’s often desperate search for meaning. Let’s honor the ancients by seeking truth, not illusion, lest we become the myths we create.

REFERENCES