Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date is October 16th 2016. A teenage boy wearing headphones helps his grandmother off a bus. She tells him to put away the headphones out of respect as they walk toward the magnificent Piazza San Pietro – Saint Peter’s Square – in the heart of Rome, in the very heart of the Catholic world. The two had traveled far from their small town in Michoacán, Mexico, to witness the canonization of a 14-year old boy named José Sánchez del Río who had been martyred in their home country at the hands of the federales in 1928. The Mexican grandmother is dressed in black and wears on her head the lace mantilla made of finely woven cactus fibers that her own grandmother had given her. She approaches St. Peter’s with awe. For a woman who had never flown on a plane before and had never left her home state in Mexico, the event would be one of the highlights of her life. Among the 80,000 people in the square this sunny day, besides the pope and all his cardinals, is Argentine president Mauricio Macri and many pilgrims, like our Mexican nana, who had traveled thousands of miles for the outdoor canonization ceremonies.

The date is October 16th 2016. A teenage boy wearing headphones helps his grandmother off a bus. She tells him to put away the headphones out of respect as they walk toward the magnificent Piazza San Pietro – Saint Peter’s Square – in the heart of Rome, in the very heart of the Catholic world. The two had traveled far from their small town in Michoacán, Mexico, to witness the canonization of a 14-year old boy named José Sánchez del Río who had been martyred in their home country at the hands of the federales in 1928. The Mexican grandmother is dressed in black and wears on her head the lace mantilla made of finely woven cactus fibers that her own grandmother had given her. She approaches St. Peter’s with awe. For a woman who had never flown on a plane before and had never left her home state in Mexico, the event would be one of the highlights of her life. Among the 80,000 people in the square this sunny day, besides the pope and all his cardinals, is Argentine president Mauricio Macri and many pilgrims, like our Mexican nana, who had traveled thousands of miles for the outdoor canonization ceremonies.  Hanging on the front of the Basilica are the banners bearing the likenesses of the 6 other people to be granted sainthood along with Mexico’s newest saint, among them an 18th Century French nun and Argentina’s “guacho priest” who ministered to the poor and eventually died of leprosy.

Hanging on the front of the Basilica are the banners bearing the likenesses of the 6 other people to be granted sainthood along with Mexico’s newest saint, among them an 18th Century French nun and Argentina’s “guacho priest” who ministered to the poor and eventually died of leprosy.

To understand the boy saint’s life and death, we have to examine the times in which he was alive. José Sánchez del Río lived during a dark and often unexamined period in Mexican history. As a young boy from a deeply religious family, little José found himself in the middle of the Cristero War also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada, a brutal internal conflict that lasted between 1926 and 1929 and pitted rural Catholic lay people and clergymen against the forces of the anti-Catholic, anti-clerical central government in Mexico City headed by President Plutarco Calles. Calles sought to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the new Constitution of 1917 produced by the Mexican Revolution and enacted legislation to reduce the power of the Church. This so-called Calles Law was seen as a continuation of the long struggle of Church versus State that dated back to La  Reforma of the mid-19th Century. Under this law restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacán. By 1927 all priests were prohibited from celebrating the mass and ordered confined to their residences or to relocate to urban areas. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many, defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. Curiously, two groups from the United States involved themselves in this war. The Knights of Columbus, a service arm of the Catholic Church, donated money to the Cristero movement. When the first donation of the Knights was announced, another group of Americans calling themselves knights – the Ku Klux Klan – offered President Calles $10,000 to fight against the Cristeros. By 1928, Dwight Whitney Morrow, the US Ambassador to Mexico at the time became involved and eventually helped broker a truce between government forces and the Cristeros. In the end, approximately a quarter million people on both sides died in the fighting.

Reforma of the mid-19th Century. Under this law restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacán. By 1927 all priests were prohibited from celebrating the mass and ordered confined to their residences or to relocate to urban areas. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many, defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. Curiously, two groups from the United States involved themselves in this war. The Knights of Columbus, a service arm of the Catholic Church, donated money to the Cristero movement. When the first donation of the Knights was announced, another group of Americans calling themselves knights – the Ku Klux Klan – offered President Calles $10,000 to fight against the Cristeros. By 1928, Dwight Whitney Morrow, the US Ambassador to Mexico at the time became involved and eventually helped broker a truce between government forces and the Cristeros. In the end, approximately a quarter million people on both sides died in the fighting.

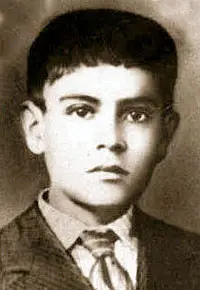

José Sánchez del Río was born on March 28th 1913 in the town of Sahuayo, Michoacán, in the central part of Mexico near Lake Chapala. His parents were Macario Sánchez Sánchez and María del Río Arteaga. Little José had two older brothers who had joined the Cristero movement. After witnessing the execution of a local Cristero leader whom he admired, the 13-year-old José was determined to join up with the Cristeros to fight for his faith. He asked permission of his parents and they reluctantly agreed. José left town with a childhood friend, Trinidad Flores, and in the mountains they met up with a band of Cristero fighters. The men thought the boys too young to fight and told them they could be a part of their group but only serve a supporting role. José and Trinidad wanted to take up arms against the enemy, so they left the group and found another band under the leadership of General Luís Guizar which took them in and trained them to fight.

José Sánchez del Río was born on March 28th 1913 in the town of Sahuayo, Michoacán, in the central part of Mexico near Lake Chapala. His parents were Macario Sánchez Sánchez and María del Río Arteaga. Little José had two older brothers who had joined the Cristero movement. After witnessing the execution of a local Cristero leader whom he admired, the 13-year-old José was determined to join up with the Cristeros to fight for his faith. He asked permission of his parents and they reluctantly agreed. José left town with a childhood friend, Trinidad Flores, and in the mountains they met up with a band of Cristero fighters. The men thought the boys too young to fight and told them they could be a part of their group but only serve a supporting role. José and Trinidad wanted to take up arms against the enemy, so they left the group and found another band under the leadership of General Luís Guizar which took them in and trained them to fight.

The boy was soon battle-tested, but his military service would not last long. In early February of 1928, the Cristeros ambushed the federales, somewhere between the towns of Cotija and Jiquilpan. The government troops opened fire with machine guns and a bullet hit General Guizar’s horse. With the enemy fast approaching, little José gave the general his own horse and told him that he was more important. The general rode off encouraging him to run but the boy stayed and fought and was soon captured. Many of the surviving Cristeros from that battle were offered deals to surrender or were executed on

the spot. José and another boy of his same age named Lorenzo, were given the opportunity to fight for the anti-Catholic side. The future boy saint told the officers that he was only captured because he ran out of ammunition, but he vowed to keep up the resistance. His friend Lorenzo stood by him and they were both taken to a prison in Cotija.

While in prison, José was allowed to write to his parents. The letter he wrote to his mother dated February 6, 1928 survives. It reads:

My dear mother:

I was made a prisoner in battle today. I think I will die soon, but I do not care, mother. Resign yourself to the will of God. I will die happy because I die on the side of our God. Do not worry about my death, which would mortify me. Tell my brothers to follow the example that their youngest brother leaves them, and do the will of God. Have courage and send me your blessing along with my father’s.

Send my regards to everyone one last time and finally receive the heart of your son who loves you so much and who wanted to see you before dying.

— José

The day after he wrote the letter José was transferred to the Catholic church in the town of Sahuayo where he was baptized. The government had transformed the church into an annex of their local military headquarters. The altar and pews were destroyed and used for firewood, the main body of the church was used to house military supplies and as a stockade of sorts for all types of animals. José’s town church, which was once a beautiful place of worship, had turned into a defiled and vandalized skeleton of its former self.

The day after he wrote the letter José was transferred to the Catholic church in the town of Sahuayo where he was baptized. The government had transformed the church into an annex of their local military headquarters. The altar and pews were destroyed and used for firewood, the main body of the church was used to house military supplies and as a stockade of sorts for all types of animals. José’s town church, which was once a beautiful place of worship, had turned into a defiled and vandalized skeleton of its former self.

News of the boy’s imprisonment spread throughout the town and attempts were made to obtain his release. The soldiers would not relent. The mayor of Sahuayo, Rafael Picazo, just so happened to be José’s godfather. Picazo was a federal sympathizer and firmly against the Cristero movement. He visited his godson in the makeshift prison at the former church and offered him a deal: he would let José go either if he would renounce his allegiance to the rebels, attend military school and then become an officer in the Mexican Army, or if he would agree to live in exile in the United States. The boy looked at Picazo and yelled:

“ I’d rather die first! I will not go with those monkeys! Never with those persecutors of the Church! If you let me go, tomorrow I will return to the Cristeros.” He ended his diatribe with the usual Cristero mantra: “Viva Cristo Rey! Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe!” which, in English means, “Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!”

Picazo’s frustration with the boy increased as did pressure from the town for the boy’s release. The last straw happened on February 9th when José was allowed to leave his cell for a bathroom break. Disgusted at what his church had become, the boy broke the necks of all the fighting roosters that were roaming around his former place of worship. The prized fighting birds belonged to Mayor Picazo. When the man heard of what happened to his property, he issued the order for the execution of the young José Sánchez del Río.

The boy was scheduled to be shot at 8:30 on the night of February 10, 1928. José was allowed one final letter to his family, which he wrote, and one final meal, delivered to him by his Aunt Magdalena. In the dinner she smuggled in a small wafer of the Blessed Sacrament, so the future saint could have his final Holy Communion. When his aunt visited him José seemed calm and resigned to his fate. He told the tearful Magdalena, “We will see each other in Heaven soon.”

Before the execution, Picazo wanted the boy to suffer. He instructed the soldiers to lash the bottom of José’s feet, and they beat him repeatedly. With each beating, the boy cried out the Cristero cry, “Viva Cristo Rey!” Picazo wanted the boy to be killed quietly, away from the eyes of the townsfolk, so they made him walk with his bloodied feet to the cemetery at the end of Constitution Street – the boy’s own Via Dolorosa – where they gave him one last chance to deny his faith. The boy refused and was hit in the jaw with a rifle butt. Another soldier stabbed him repeatedly, and with each thrust of the knife, the boy professed his loyalty to Christ. Moments before his death, José drew a cross in the dirt and kissed it. His life finally ended when one of the soldiers shot him behind the ear. His body was thrown into a shallow grave and covered with dirt. The caretaker of the cemetery later contacted a local priest, Father Ignacio Sánchez, who exhumed the boy’s body, wrapped it in white sheets and prayed over him. Thus, the boy José Sánchez del Río became a Catholic martyr with the path to sainthood paved by Pope Benedict the Sixteenth who beatified him on his visit to Mexico on November 20th 2005. After a medical miracle was ascribed to the intercession of the Blessed José Sánchez del Río in 2015, Pope Francis declared him a saint on October 16th 2016, telling a congregation of thousands that little José would always be remembered for his fortitude, valor, hope and his holy audacity. A very sad story, it seems, has given Mexicans and other faithful people cause to reflect upon and celebrate the brief life of an extraordinary young boy.

Before the execution, Picazo wanted the boy to suffer. He instructed the soldiers to lash the bottom of José’s feet, and they beat him repeatedly. With each beating, the boy cried out the Cristero cry, “Viva Cristo Rey!” Picazo wanted the boy to be killed quietly, away from the eyes of the townsfolk, so they made him walk with his bloodied feet to the cemetery at the end of Constitution Street – the boy’s own Via Dolorosa – where they gave him one last chance to deny his faith. The boy refused and was hit in the jaw with a rifle butt. Another soldier stabbed him repeatedly, and with each thrust of the knife, the boy professed his loyalty to Christ. Moments before his death, José drew a cross in the dirt and kissed it. His life finally ended when one of the soldiers shot him behind the ear. His body was thrown into a shallow grave and covered with dirt. The caretaker of the cemetery later contacted a local priest, Father Ignacio Sánchez, who exhumed the boy’s body, wrapped it in white sheets and prayed over him. Thus, the boy José Sánchez del Río became a Catholic martyr with the path to sainthood paved by Pope Benedict the Sixteenth who beatified him on his visit to Mexico on November 20th 2005. After a medical miracle was ascribed to the intercession of the Blessed José Sánchez del Río in 2015, Pope Francis declared him a saint on October 16th 2016, telling a congregation of thousands that little José would always be remembered for his fortitude, valor, hope and his holy audacity. A very sad story, it seems, has given Mexicans and other faithful people cause to reflect upon and celebrate the brief life of an extraordinary young boy.

REFERENCES: Various Internet sources.

3 thoughts on “José Sánchez del Río, Mexico’s Boy Saint”

This information is very, very incorrect

How so?

DSeer98,

Do you have the correct version and if you do, please tell me where I can find it? Were you there or did the government at the time told you about it? Be more specific please!