Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

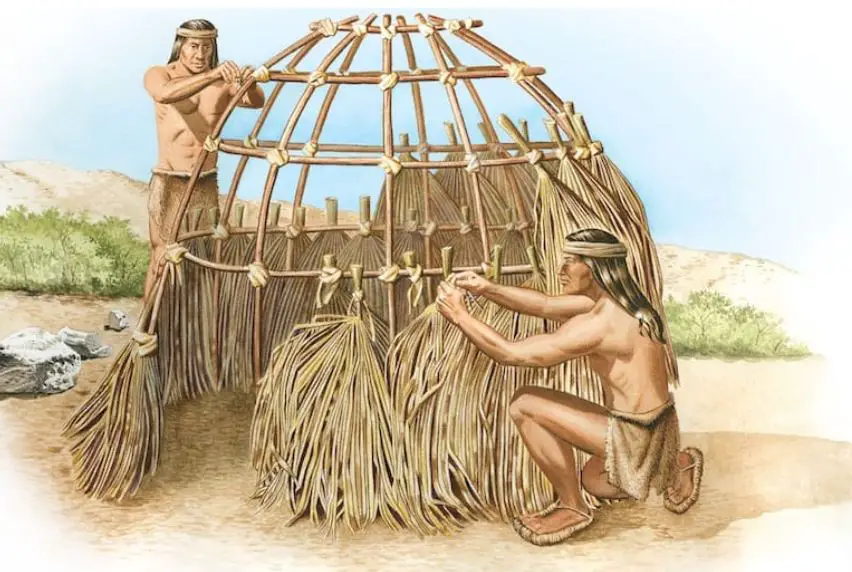

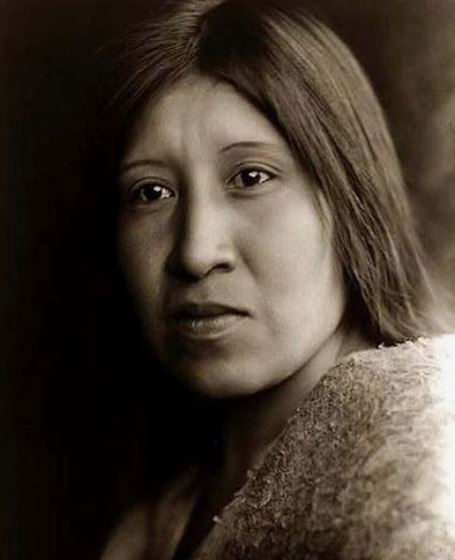

In a remote canyon on the fringes of Spain’s empire in the New World, a child was born. This notable birth happened in the early 1780s around the time the Spanish founded El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula, known today simply as Los Angeles. The child was part of a mountain band of Cahuilla people who lived in what is now called San Timoteo Canyon about 15 miles southeast of the modern-day city center of San Bernardino, California. The boy’s name in the Cahuilla language was Cooswootna, which loosely translates into English as, “He who is quick to anger.” He would be known to the Spanish, and later to the Mexicans and Americans as Juan Antonio. Legend has it that Juan Antonio’s mother made a 25-mile trek to a sacred mountain to give birth to him. This mountain, known today as Mount San Jacinto, was known to the natives as I a Kitch, or “Smooth Cliffs,” in English. This mountain was home to a powerful spirit known to many southern California peoples as the Dakush, Taqwus or Tahquitz. The following is a description of this supernatural being from the website of the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians:

In a remote canyon on the fringes of Spain’s empire in the New World, a child was born. This notable birth happened in the early 1780s around the time the Spanish founded El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula, known today simply as Los Angeles. The child was part of a mountain band of Cahuilla people who lived in what is now called San Timoteo Canyon about 15 miles southeast of the modern-day city center of San Bernardino, California. The boy’s name in the Cahuilla language was Cooswootna, which loosely translates into English as, “He who is quick to anger.” He would be known to the Spanish, and later to the Mexicans and Americans as Juan Antonio. Legend has it that Juan Antonio’s mother made a 25-mile trek to a sacred mountain to give birth to him. This mountain, known today as Mount San Jacinto, was known to the natives as I a Kitch, or “Smooth Cliffs,” in English. This mountain was home to a powerful spirit known to many southern California peoples as the Dakush, Taqwus or Tahquitz. The following is a description of this supernatural being from the website of the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians:

“Tahquitz was the first shaman created by Mukat, the creator of all things. Tahquitz had much power, and in the beginning, he used his power for the good of all people. Tahquitz became the guardian spirit of all shamans and he gave them power to do good. But over time, Tahquitz began to use his power for selfish reasons. He began to use his power to harm the Cahuilla People. The people became angry, and they banished Tahquitz to this canyon that now bears his name. He made his home high in the San Jacinto Mountains in a secret cave below the towering rock known today as Tahquitz Peak. It is said that his spirit still lives in this canyon. He can sometimes be seen as a large green fireball streaking across the night sky. The strange rumblings heard deep within the San Jacinto Mountains, the shaking of the ground, and the crashing of boulders are all attributed to Tahquitz as he stomps about the canyon.”

This legend tied to Juan Antonio’s place of birth may have influenced how the young warrior was perceived by others and even how he perceived himself. Little is known about Juan Antonio’s early years other than he was very skilled with a bow and arrow. His band of Cahuilla people in San Timoteo Canyon was seemingly cut off from the rest of the world and even had limited interaction with other Cahuilla bands in the surrounding area. That was, until 1806 when Juan Antonio was about 22 or 23 years old and already seen as a leader of his people.

Starting in 1806, Spanish officials began exploring the interior of what was then known as Alta California in search of new sites on which to build missions and presidios. The mission system in California had been established just 37 years before; the first one built in 1769 was Misión San Diego de Alcalá, located just 4 miles from where I am now recording this episode of Mexico Unexplained. In the few decades of the fragile mission system on the fringes of Spain’s empire, the Catholic fathers and their military supporters faced constant hostility from the native tribes of the mountains and deserts of the vast, unexplored interior. Groups of Cahuilla, Shoshone and others would regularly raid the small Spanish settlements and ranchos located closer to the coast to steal horses and to take captives. The Spanish garrisons at the presidios were often overwhelmed and outnumbered. By the early 1800s the Spanish saw the need for a buffer zone between the already-established coastal settlements and the seemingly unfriendly interior. In 1806 an expedition led by Father José María Zalvidéa pushed into the territory of Juan Antonio’s people, exploring the San Bernardino Valley and making it all the way to the Mohave River. Meanwhile up north, Spanish clerics plied the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys, sometimes without military escorts, looking for suitable places to establish forts and missions.

Starting in 1806, Spanish officials began exploring the interior of what was then known as Alta California in search of new sites on which to build missions and presidios. The mission system in California had been established just 37 years before; the first one built in 1769 was Misión San Diego de Alcalá, located just 4 miles from where I am now recording this episode of Mexico Unexplained. In the few decades of the fragile mission system on the fringes of Spain’s empire, the Catholic fathers and their military supporters faced constant hostility from the native tribes of the mountains and deserts of the vast, unexplored interior. Groups of Cahuilla, Shoshone and others would regularly raid the small Spanish settlements and ranchos located closer to the coast to steal horses and to take captives. The Spanish garrisons at the presidios were often overwhelmed and outnumbered. By the early 1800s the Spanish saw the need for a buffer zone between the already-established coastal settlements and the seemingly unfriendly interior. In 1806 an expedition led by Father José María Zalvidéa pushed into the territory of Juan Antonio’s people, exploring the San Bernardino Valley and making it all the way to the Mohave River. Meanwhile up north, Spanish clerics plied the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys, sometimes without military escorts, looking for suitable places to establish forts and missions.

By 1810 the situation for the Spanish in southern California became dire. In central Mexico the Spanish military was dealing with the beginnings of the Mexican War of Independence and the Spanish Crown refused to shunt resources to protect the few hundred of their subjects on the northern frontier. The settlers of California were forced to fend for themselves. In November of 1810, some 800 indigenous warriors, mostly Mohaves from the Colorado River area traveled hundreds of miles, gaining numbers from other tribes along the way, and threatened to annihilate the missions of San Gabriel and San Fernando and promised to burn the small pueblo of Los Angeles to the ground. Along the way, this group of 800 pillaged and destroyed the small ranchos that struggled to exist in the interior. Meanwhile, Spanish troops from the faraway presidios of Santa Barbara and San Diego were sent to confront the 800 natives and to protect whatever property they could in the area this large group was set to move through. The Spanish were somewhat successful in driving back this mass of indigenous resistors, but fractions of this group kept coming back in small raiding parties. History is not clear whether Juan Antonio participated in these raids or whether he was part of the Mohave-led group of 800. Spanish records at the time tell the tale of the seemingly fruitless European defense of southern California. In the expedition against the 800, for example, Spanish documents in Mexico City archives show that some 3,000 stolen sheep were recovered by the military. Also in these archives, we see as an example the service record of Corporal José Pico, from the famous California Pico family, that he led 14 expeditions against hostile natives adjacent to Mission San Gabriel in the year 1810 alone. By 1811, the head of the California mission system, Father Estevan Tapis reported this to his superiors in Mexico City:

“No place in the direction of the Colorado River suitable for founding a mission having been discovered, and such a foundation being impossible without a strong garrison, it would be expedient to enlarge the guard at San Gabriel.”

The Spanish did not expand their military resources at vulnerable San Gabriel. It seemed that the indigenous resistance was working, at least temporarily, and the mountain Cahuilla led by Juan Antonio would be left in peace to live as they had for thousands of years. Then a new nation came on the scene, a country called Mexico, which had different designs on the northern territories that Spain had neglected and mismanaged. Juan Antonio saw the world around him begin to change, and in the wisdom of his years he knew he had to change his strategy if his people were to survive.

The Spanish did not expand their military resources at vulnerable San Gabriel. It seemed that the indigenous resistance was working, at least temporarily, and the mountain Cahuilla led by Juan Antonio would be left in peace to live as they had for thousands of years. Then a new nation came on the scene, a country called Mexico, which had different designs on the northern territories that Spain had neglected and mismanaged. Juan Antonio saw the world around him begin to change, and in the wisdom of his years he knew he had to change his strategy if his people were to survive.

As the new government of Mexico encouraged settlement of Alta California, the region saw an influx of not only mestizo people from other parts of Mexico, but increasing numbers of settlers from European countries and the United States. Newcomers from other countries were promised land and Mexican citizenship. The natives in the desert and mountain areas were still considered safe, though, because the new settlers were not interested in those areas. The indigenous people did see what was going on, however, and the raiding and threats of raids continued, although to a lesser degree. An unwritten détente, or cessation of hostilities, occurred in the early years of Mexican independence. During this time Juan Antonio and members of his band often worked for the larger Mexican landowners of the area when the situations called for them to do so. The Cahuilla leader saw the importance of maintaining peace in this rapidly changing world.

By 1829 another major event occurred that would change the lives of the desert and mountain peoples of Mexican California. A man named Antonio Armijo from Santa Fé, in the Mexican province of Nuevo México, planned a bold thousand-mile journey of commerce to link New Mexico with California in an overland trade route. With 60 mounted men and a caravan of pack animals, Armijo’s expedition left the town of Abiquiú, New Mexico on November 7, 1829, and made the journey to the San Gabriel Mission in 86 days, arriving on January 31, 1830. He returned by the same way in 56 days, leaving on March 1 and arriving on April 25, 1830. This route would later be called the Old Spanish Trail. Armijo kept detailed notes along his arduous journey and compiled them into a report to help future travelers make the trek from New Mexico to California. Armijo submitted his report to the Mexican governor of New Mexico José Antonio Cháves, and the Mexican government published his report on June 19, 1830. These trade caravans would bring more people through Cahuilla territory and more resentment from the desert and mountain natives. Hostile Indian activity was on the upswing again as more and more traders crossed the mountains and deserts exchanging woven goods and American-made products from Santa Fé for horses, mules and luxury goods from the Orient available in Los Angeles. Although subject to indigenous attacks, subsequent caravans were better armed and over time the natives didn’t have a chance against them or the increasing settler population surrounding them.

It was during the 1830s when Juan Antonio made an alliance with Antonio Maria Lugo, former Los Angeles mayor and one of the city’s richest land barons. The mountain Cahuilla were not raiders and did not want to be associated with those who were violent and fighting what seemed to be a protracted losing battle. Juan Antonio encouraged other tribes to stop raiding and try to coexist peacefully in this ever-changing world. He had great conflict with the native leader Walkara who lived hundreds of miles away in the Great Basin in what is now Nevada and Utah. Walkara would organize raiding parties of hundreds of Ute, Paiute and Shoshone and would descend upon the Mexican settlements of California. Juan Antonio managed to convince many of Walkara’s followers to lay down their arms. As the Cahuilla people were the closest natives with homelands near the growing Mexican settlements, they had more to lose from the violent actions of other natives who lived hundreds of miles away and far from the Mexican centers of power. Juan Antonio was caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place. While he sympathized with the indigenous resistance, he knew that he had to interact peacefully with the Mexicans if his people were to survive. Walkara’s raids were such disasters for the Mexicans of California that Antonio Lugo encouraged and paid for settlements to be populated by people from New Mexico to act as a buffer between his lands and possible future raids. The main settlement of New Mexicans was called Politana, and it was abandoned within a year. After its abandonment in the early 1840s, Antonio Lugo gave the town and the surrounding area to Juan Antonio and the mountain Cahuilla.

Juan Antonio and his band fought on the Mexican side during the Mexican American War because of his loyalty to the Lugo family. During one notable battle, Lugo and his men joined Juan Antonio and some 50 of his Cahuilla fighters to ambush a band of Luiseño Indians that had killed 11 Mexican troopers in a surprise attack. After the fighting, Lugo handed the Luiseño captives over to Juan Antonio, who promptly killed all of them.

The Mexicans lost the war and Juan Antonio found he had to navigate new waters if he wanted his people and their allies to survive under US domination. In 1851, the American press was associating Juan Antonio with another Cahuilla leader named Antonio Garra who was hostile to the Americans and continued the long practice of raiding and pillaging. Rumors floating around southern California at the time said that Juan Antonio and Antonio Garra planned on killing every white person from Santa Barbara to San Diego. Seeing how bad this was for peaceful coexistence with the Americans, Juan Antonio called for a face-to-face meeting with Antonio Garra to try to convince his fellow Cahuilla leader to cease hostilities. When Garra rode into Juan Antonio’s camp, he was captured. Garra’s son took out a knife and lunged at Juan Antonio, cutting his arm and side. Garra was detained, handed over to US authorities and subsequently convicted and shot.

The Mexicans lost the war and Juan Antonio found he had to navigate new waters if he wanted his people and their allies to survive under US domination. In 1851, the American press was associating Juan Antonio with another Cahuilla leader named Antonio Garra who was hostile to the Americans and continued the long practice of raiding and pillaging. Rumors floating around southern California at the time said that Juan Antonio and Antonio Garra planned on killing every white person from Santa Barbara to San Diego. Seeing how bad this was for peaceful coexistence with the Americans, Juan Antonio called for a face-to-face meeting with Antonio Garra to try to convince his fellow Cahuilla leader to cease hostilities. When Garra rode into Juan Antonio’s camp, he was captured. Garra’s son took out a knife and lunged at Juan Antonio, cutting his arm and side. Garra was detained, handed over to US authorities and subsequently convicted and shot.

In the early 1850s, the Lugos sold their properties in what is now San Bernardino to Mormon settlers and Juan Antonio’s services were no longer required. He and members of his band quietly removed themselves from modern society and returned to San Timoteo Canyon to live out their lives peacefully in the traditional land of their ancestors. The outside world left them alone. In 1863, then over 80 years old, Juan Antonio died alone from smallpox, leaving behind a complicated legacy spanning 2 centuries and 3 countries.

For more episodes about indigenous resistance in northern Mexico and the southwestern US, please click below:

The Comanche: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-comanche-wars-1821-1870/

The Apache: https://mexicounexplained.com/apache-wars-with-mexico/

REFERENCES

Beattie, George William. “San Bernardino Valley before the Americans Came.” California Historical Society Quarterly 12, no. 2 (1933): 111–24.

Rasmussen, Cecilia. “Indian Chief was Tough Friend, Foe.” Los Angeles Times. 11 April 1999.