Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Less than an hour’s drive from downtown Hermosillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Sonora, there exists a very important and relatively unknown archaeological site. About 40 miles south of the bustling city on Highway 15 past the Pemex station before the small town of Las Avispas, a small dirt road takes the traveler to another time and place. Looming before the visitor is the small mountain range named the Sierra Libre, or “Free Mountains,” so called by the Spanish because it was once home to escaped indigenous slaves and other fleeing renegades in early colonial times. This small mountainous area seems a little out of place rising above the inhospitable desert which stretches out flat in all directions. The Sierra Libre is indeed a very unique place. Within those mountains are deep canyons and springs, tall trees that provide endless shade, and a very temperate climate with a feel to it that is so unlike the surrounding wasteland. Within its passes and canyons even the temperature is cooler and more humid than in the hot Sonoran Desert which completely encircles this distinctive massif. The indigenous peoples of northern Mexico knew how special the Sierra Libre was. In fact, this place may have been known to people who lived as far away as the modern US state of Arizona. For thousands of years many different peoples enjoyed these mountains and saw them as sacred. Well into the 21st Century, researchers are only beginning to understand the importance of the archaeological zone now called “La Pintada” by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History or INAH. INAH became the custodian of the most archaeologically significant part of the Sierra around La Pintada Canyon in the early 2000s after the Mexican government bought over 30 hectares of land from the municipality of Hermosillo. Although the area was briefly studied in the 1960s and ‘70s, the purchase of the land and its immediate fencing off represented the beginning of formal, intensive research.

Less than an hour’s drive from downtown Hermosillo, the capital of the Mexican state of Sonora, there exists a very important and relatively unknown archaeological site. About 40 miles south of the bustling city on Highway 15 past the Pemex station before the small town of Las Avispas, a small dirt road takes the traveler to another time and place. Looming before the visitor is the small mountain range named the Sierra Libre, or “Free Mountains,” so called by the Spanish because it was once home to escaped indigenous slaves and other fleeing renegades in early colonial times. This small mountainous area seems a little out of place rising above the inhospitable desert which stretches out flat in all directions. The Sierra Libre is indeed a very unique place. Within those mountains are deep canyons and springs, tall trees that provide endless shade, and a very temperate climate with a feel to it that is so unlike the surrounding wasteland. Within its passes and canyons even the temperature is cooler and more humid than in the hot Sonoran Desert which completely encircles this distinctive massif. The indigenous peoples of northern Mexico knew how special the Sierra Libre was. In fact, this place may have been known to people who lived as far away as the modern US state of Arizona. For thousands of years many different peoples enjoyed these mountains and saw them as sacred. Well into the 21st Century, researchers are only beginning to understand the importance of the archaeological zone now called “La Pintada” by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History or INAH. INAH became the custodian of the most archaeologically significant part of the Sierra around La Pintada Canyon in the early 2000s after the Mexican government bought over 30 hectares of land from the municipality of Hermosillo. Although the area was briefly studied in the 1960s and ‘70s, the purchase of the land and its immediate fencing off represented the beginning of formal, intensive research.

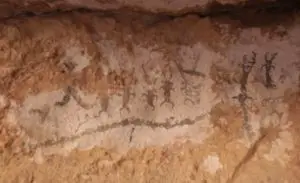

The site of La Pintada contains two components: The magnificent rock art decorating the many canyon and cave walls, and the ancient camp sites found in caves and open areas. Unlike many of the more famous or glamorous Aztec or Maya sites, La Pintada contains no structures, no buildings of any kind. This does not mean the site is insignificant. It does seem to explain, though, why La Pintada has been ignored for so long by serious researchers and the Mexican government. The ancient camp sites found here provide a treasure-trove of information about how the ancient people of northwestern Mexico lived, however. Archaeologists have been piecing together the story of this place without having gigantic monuments full of inscriptions to tell the tale of what happened here long ago. Researchers have been busy classifying ceramics, stone tools, grinding artifacts and worked seashells, along with floral and faunal remains found at the site. The rock art found throughout the cliffsides, canyons and cave walls number to over 2,500 distinct, catalogued images. The paintings are of what the ancient indigenous people saw around them in their natural environment, specifically, animals such as birds, deer and reptiles. There are curious repeating geometric patterns throughout La Pintada that some have likened to being part of an ancient alphabet, but the official explanation for these designs from the National Institute of Anthropology and History is that there is no official explanation for them. A curious hourglass-looking symbol, comprised of two framed triangles has been seen in other parts of Mexico and appears at La Pintada, but no one knows its meaning. As with most other rock art sites throughout Mexico and in other parts of the world, many of the images at La Pintada have been painted over older designs or have been retouched or enhanced by later unknown prehistoric artists. Researchers have recognized over 400 different style or design types, that cut across large swaths of time and possible ethnic groups.

The site of La Pintada contains two components: The magnificent rock art decorating the many canyon and cave walls, and the ancient camp sites found in caves and open areas. Unlike many of the more famous or glamorous Aztec or Maya sites, La Pintada contains no structures, no buildings of any kind. This does not mean the site is insignificant. It does seem to explain, though, why La Pintada has been ignored for so long by serious researchers and the Mexican government. The ancient camp sites found here provide a treasure-trove of information about how the ancient people of northwestern Mexico lived, however. Archaeologists have been piecing together the story of this place without having gigantic monuments full of inscriptions to tell the tale of what happened here long ago. Researchers have been busy classifying ceramics, stone tools, grinding artifacts and worked seashells, along with floral and faunal remains found at the site. The rock art found throughout the cliffsides, canyons and cave walls number to over 2,500 distinct, catalogued images. The paintings are of what the ancient indigenous people saw around them in their natural environment, specifically, animals such as birds, deer and reptiles. There are curious repeating geometric patterns throughout La Pintada that some have likened to being part of an ancient alphabet, but the official explanation for these designs from the National Institute of Anthropology and History is that there is no official explanation for them. A curious hourglass-looking symbol, comprised of two framed triangles has been seen in other parts of Mexico and appears at La Pintada, but no one knows its meaning. As with most other rock art sites throughout Mexico and in other parts of the world, many of the images at La Pintada have been painted over older designs or have been retouched or enhanced by later unknown prehistoric artists. Researchers have recognized over 400 different style or design types, that cut across large swaths of time and possible ethnic groups.

After the government fenced off the site, researchers and volunteers got to work documenting, cataloging and cleaning up. As an oasis in the middle of the desert so close to a major metropolitan area, La Pintada has seen thousands of visitors unchecked in just the past few decades. People would travel from Hermosillo to escape the heat in the cool ponds and hidden waterways of the Sierra Libre. Families often would make a day of it, go swimming and have cookouts. Graffiti artists and others who wished to make their marks at La Pintada also defaced some of the rock art, including some of the most interesting and elaborate panels. Given the amount of modern graffiti on the sides of the canyons and cave walls, the temptation to contribute must have been great for some individuals when encountering such concentrations of rock art, perhaps even in ancient times. In one canyon, someone in the late 1990s took a bucket of green paint and splashed it on the wall, thus obscuring dozens of ancient images. Formal cleaning and restoration efforts began at La Pintada in 2007 under the direction of Sandra Cruz who works for the National Coordination for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, a division of INAH. Over a period of 10 years, Cruz and her team cleaned and restored the many decorated surfaces at La Pintada inch by inch, sometimes hanging from scaffolding built to a height of 25 feet and in temperatures well above 90 degrees. Restorers used medical, dental and painter’s instruments as tools. In most cleaning attempts, first, the restorers hydrate the rock and then apply the paste that will reconstitute the silica networks that compose it to keep it firm, without cracks and without the danger of exfoliations. Then, cleaning solutions are applied slowly, and the type of solution used depends on many different factors. The various surfaces on which the art appears, combined with the age of the art and materials used by the ancient artists – on top of the accessibility issues – made the cleaning and restoration project a daunting, laborious task. In an interview with the Mexican press, Cruz stated:

After the government fenced off the site, researchers and volunteers got to work documenting, cataloging and cleaning up. As an oasis in the middle of the desert so close to a major metropolitan area, La Pintada has seen thousands of visitors unchecked in just the past few decades. People would travel from Hermosillo to escape the heat in the cool ponds and hidden waterways of the Sierra Libre. Families often would make a day of it, go swimming and have cookouts. Graffiti artists and others who wished to make their marks at La Pintada also defaced some of the rock art, including some of the most interesting and elaborate panels. Given the amount of modern graffiti on the sides of the canyons and cave walls, the temptation to contribute must have been great for some individuals when encountering such concentrations of rock art, perhaps even in ancient times. In one canyon, someone in the late 1990s took a bucket of green paint and splashed it on the wall, thus obscuring dozens of ancient images. Formal cleaning and restoration efforts began at La Pintada in 2007 under the direction of Sandra Cruz who works for the National Coordination for the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, a division of INAH. Over a period of 10 years, Cruz and her team cleaned and restored the many decorated surfaces at La Pintada inch by inch, sometimes hanging from scaffolding built to a height of 25 feet and in temperatures well above 90 degrees. Restorers used medical, dental and painter’s instruments as tools. In most cleaning attempts, first, the restorers hydrate the rock and then apply the paste that will reconstitute the silica networks that compose it to keep it firm, without cracks and without the danger of exfoliations. Then, cleaning solutions are applied slowly, and the type of solution used depends on many different factors. The various surfaces on which the art appears, combined with the age of the art and materials used by the ancient artists – on top of the accessibility issues – made the cleaning and restoration project a daunting, laborious task. In an interview with the Mexican press, Cruz stated:

“The complexity in the alteration of the rock and the difficult access to the main panel of the site have made La Pintada one of the greatest challenges I have ever faced.”

So, who was responsible for this magnificent rock art? Who spent time at the temporary encampments? There were many different peoples living throughout the deserts of Sonora in the times before the arrival of the Spanish. Researchers date the earliest artifacts at La Pintada to around 700 AD. There is no concrete way to date the rock paintings, but some researchers theorize that they may go back thousands of years. Archaeologists do not categorize La Pintada as being a part of Mesoamerica, that area of central and southern Mexico that was home to the grand and complex civilizations that so many people associate with the country’s prehistory. It’s too far north and there is very little evidence directly linking it with those cultures to the south. Researchers classify the zone as being a part of Aridoamerica or Oasisamerica. The term Aridoamerica is used to describe an ecological region spanning northern Mexico and the Desert Southwest of the  United States, characterized by scarce rainfall but enough sustenance on the land for people to lead a robust nomadic existence. Oasisamerica overlaps this ecological region and is used to denote those areas of northern Mexico and the Desert Southwest of the United States where water was more reliable. In Oasisamerica people settled into villages and engaged in minimal subsistence agriculture. La Pintada had a stable water source but no permanent settlements, so it is seen as a combination of Arido- and Oasisameria. As mentioned before, the various art styles as seen on the canyon and cave walls indicate different peoples moved through this area. As the themes were similar, researchers conclude this must have been a holy and special place to those who knew about it. Some believe it was a mere stopover point, while others think that it was a sacred pilgrimage destination that drew people from as far away as the Gila River valley in the modern-day state of Arizona.

United States, characterized by scarce rainfall but enough sustenance on the land for people to lead a robust nomadic existence. Oasisamerica overlaps this ecological region and is used to denote those areas of northern Mexico and the Desert Southwest of the United States where water was more reliable. In Oasisamerica people settled into villages and engaged in minimal subsistence agriculture. La Pintada had a stable water source but no permanent settlements, so it is seen as a combination of Arido- and Oasisameria. As mentioned before, the various art styles as seen on the canyon and cave walls indicate different peoples moved through this area. As the themes were similar, researchers conclude this must have been a holy and special place to those who knew about it. Some believe it was a mere stopover point, while others think that it was a sacred pilgrimage destination that drew people from as far away as the Gila River valley in the modern-day state of Arizona.

For most of the time that La Pintada was visited and used in ancient times, researchers believe there was an overlap of cultures there, as represented in the archaeological record, although they are still trying to put together a clear story. Artifacts and art styles of the cultural “traditions” of the Trincheras, Huatabampo and Central Coast are evident at La Pintada. The Trincheras culture existed from about 750 AD to 1450 and is characterized by trenches dug at sites perhaps to serve as water catchments. The Trincheras had brown and red pottery decorated with purplish paint which was very similar to the Hohokam of the ancient Gila River valley to the north. The Trincheras tradition was found mostly in the northern part of Sonora. The Huatabampo tradition is characterized by a distinctive pottery style and flourished until about 1000 AD in the central part of Sonora. The Central Coast tradition lacked agriculture and was a completely nomadic culture. Central Coast artifacts found at La Pintada include remains of hunting implements such as spearheads. The Central Coast people stayed mainly near the shores of the Gulf of California and rarely made incursions deep into the interior. There have been a few artifacts found at La Pintada that are linked to the more complex cultures of the American Southwest such as the Anasazi, Hohokam and the Mogollon peoples as well as objects from the Casas Grandes culture that flourished in northern Chihuahua until about the year 1450. This does not necessarily mean that visitors from these faraway cultures made the trip to La Pintada, although that could have been possible. It’s important to note that La Pintada was not a trading outpost. However, people leaving behind these artifacts could have acquired them as part of their personal possessions through trade without being from those cultures. No artifacts from any of the larger Mesoamerican cultures – the Toltecs, Aztecs, or Maya, for example – have yet been found at this site. In later years, La Pintada and the Sierra Libre as a whole served as a refuge for various indigenous people fleeing encroaching outside civilization. Mayos, Opatas, Yaquis and other tribes considered “Chichimeca” hid out here. Even a band of Kickapoo took temporary refuge in the Sierra Libre in the 1800s after fleeing oppression in the United States.

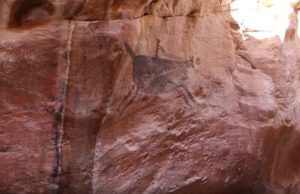

La Pintada was formally opened to the public in March of 2018 with restoration and recovery of the environment ongoing. On invitation of the Mexican government, a group of elders from the Seri tribe of coastal Sonora were invited to tour the newly opened site. The Seri were one of the last indigenous tribes to assimilate to modern Mexico and still live a somewhat isolated and traditional existence on the north central coast of the state. For more information on the Seri, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 209 https://mexicounexplained.com/seri-people-the-last-to-assimilate/ . On this visit to La Pintada one of the Seri elders cried when she saw the largest cave painting at the site, a small figure of a human riding on the back of a deer. The painting measures more than 3 feet across. The elder explained that this was a depiction of “The Powerful Boy” of Seri legend, a hero to the Seri people who was known for riding deer. The date of that specific painting is unknown, but the connection to ancient Seri tradition further reinforces the spiritual importance of La Pintada. As archaeologists are quick to admit, there is a lot more to learn here.

La Pintada was formally opened to the public in March of 2018 with restoration and recovery of the environment ongoing. On invitation of the Mexican government, a group of elders from the Seri tribe of coastal Sonora were invited to tour the newly opened site. The Seri were one of the last indigenous tribes to assimilate to modern Mexico and still live a somewhat isolated and traditional existence on the north central coast of the state. For more information on the Seri, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 209 https://mexicounexplained.com/seri-people-the-last-to-assimilate/ . On this visit to La Pintada one of the Seri elders cried when she saw the largest cave painting at the site, a small figure of a human riding on the back of a deer. The painting measures more than 3 feet across. The elder explained that this was a depiction of “The Powerful Boy” of Seri legend, a hero to the Seri people who was known for riding deer. The date of that specific painting is unknown, but the connection to ancient Seri tradition further reinforces the spiritual importance of La Pintada. As archaeologists are quick to admit, there is a lot more to learn here.

REFERENCES

INAH web site (in Spanish): https://www.inah.gob.mx/boletines/5248-se-cumplen-diez-anos-de-investigacion-arqueologica-y-restauracion-en-la-pintada-sonora