Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

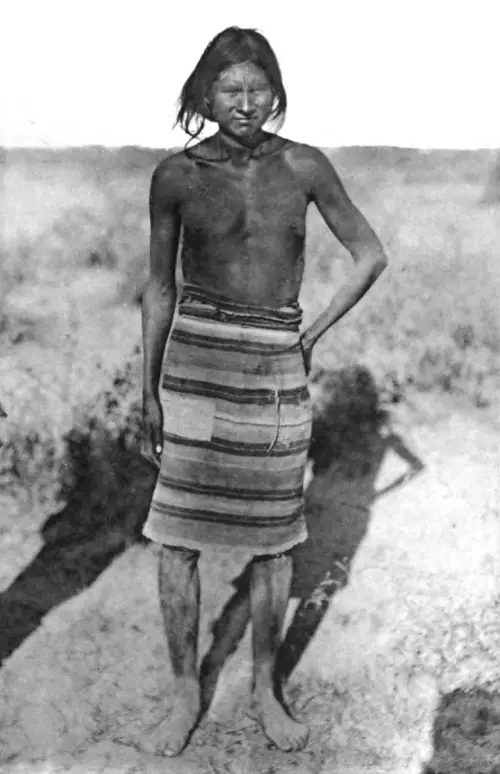

In his grand transcontinental journey, Spanish explorer Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca skirted one of the most inhospitable deserts in the whole world in what is now northwestern Mexico in the present-day Mexican state of Sonora. It was a rather warm day in April 1536, less than 20 years after Cortés had conquered the Aztecs. The Cabeza de Vaca expedition encountered a group of nomadic people, barely clothed, wearing necklaces of pearls and rattlesnake tails. The small indigenous band followed alongside the Spanish party, keeping a good distance, and although seemingly curious, they made no formal contact. In his diary Cabeza de Vaca wrote:

In his grand transcontinental journey, Spanish explorer Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca skirted one of the most inhospitable deserts in the whole world in what is now northwestern Mexico in the present-day Mexican state of Sonora. It was a rather warm day in April 1536, less than 20 years after Cortés had conquered the Aztecs. The Cabeza de Vaca expedition encountered a group of nomadic people, barely clothed, wearing necklaces of pearls and rattlesnake tails. The small indigenous band followed alongside the Spanish party, keeping a good distance, and although seemingly curious, they made no formal contact. In his diary Cabeza de Vaca wrote:

“On the coast there is no maize: the inhabitants eat the powder of rush and of straw, and fish that is caught in the sea from rafts, not having canoes. With grass and straw, the women cover their nudity. They are a timid and dejected people.”

This was the first European description of the Seris, a people who still live on the coastal deserts of the Sea of Cortez, one of the last indigenous groups to assimilate into broader Mexican society. Today, they number about two thousand with most Seris still living in their ancestral homeland and several hundred still speaking their native language, called cmiique iitom. Their language puzzles linguists and is considered a language isolate in that it has no related languages that exist anywhere on earth. The Seris call themselves the Comcaac and the name “Seri” is believed to be a name given to this group by the neighboring Yaqui people. “Seri” may mean “people of the desert,” in an extinct Yaqui dialect, but this is not certain. Some researchers also believe that the name comes from the language of Opata people who lived northeast of Seri territory. The Seris are not related to other neighboring indigenous groups.

Outsiders had very little interest in Seri territory which they considered to be too harsh and not viable to develop or exploit. Missionaries arrived in the 1690s and were met with hostility. Early Spanish interlopers, who arrived in Seriland even before the missionaries, described a warlike people unwelcoming of foreigners. In one account of early Seri warriors, a Spanish explorer wrote in letters back to Europe that although the Seri fighter had a club, sticks and bow and arrow at his disposal, the Seri’s weapon of choice was his own body. Many outsiders were ambushed and jumped with warriors choking their victims and biting them. According to this explorer, he had, “greater fear of the throttling hands and rending teeth of the savage warriors than of all their artificial weapons combined.” The neighboring Yaqui and Opata tribes minimized their contact with the Seris because of this viciously unique way of fighting. The Seris’ intense hand-to-hand combat likely fueled unfounded tales of cannibalism that kept away curious foreigners for centuries, although stories of gold on Tiburón Island brought a few intrigued fortune hunters from other parts of Mexico and even the United States in later years. In most cases, those bitten by the gold bug did not make it out of Seri territory alive, succumbing to the elements or meeting their demise at the hands of the less-than-welcoming Seris. According to the Seri creation story there were once 12 bands of Seris originating from 12 sisters. These 12 bands once roamed the entire length of the northeastern shores of the Sea of Cortez in the modern Mexican state of Sonora with part of one band living across the sea in the eastern coast of Baja. In more recent times anthropologists  have identified 6 distinct groups which eventually blended into the one single group we see today. The Seris now live in two municipalities on the mainland, Punta Chueca and El Desemboque, and seasonal encampments on the islands of Tiburón, also called Tahejoc, and San Esteban, also called Cofteecol. The Mexican government granted Tiburón Island to the Seris to be held in trust by the tribe and it is now part of an ecological zone administered by the Seri people. It contains many sacred sites including a series of caves. The Seris believe that the island was the first piece of land to exist on earth. When the world was covered in water, a gigantic sea turtle flapped mud on his back and this became Tiburón Island. For another interesting legend about this place, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 145 titled “The White Giants of Tiburón Island.” https://mexicounexplained.com//the-white-giants-of-tiburon-island/

have identified 6 distinct groups which eventually blended into the one single group we see today. The Seris now live in two municipalities on the mainland, Punta Chueca and El Desemboque, and seasonal encampments on the islands of Tiburón, also called Tahejoc, and San Esteban, also called Cofteecol. The Mexican government granted Tiburón Island to the Seris to be held in trust by the tribe and it is now part of an ecological zone administered by the Seri people. It contains many sacred sites including a series of caves. The Seris believe that the island was the first piece of land to exist on earth. When the world was covered in water, a gigantic sea turtle flapped mud on his back and this became Tiburón Island. For another interesting legend about this place, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 145 titled “The White Giants of Tiburón Island.” https://mexicounexplained.com//the-white-giants-of-tiburon-island/

The sea turtle that features prominently in the beliefs of the Seris was once their primary source of food. Before the arrival of the Spanish and even for centuries after, the Seris lived a hunter-gatherer existence relying on the sea for most of their food. The sea turtle, various types of fish and mollusks and even pelicans formed the bulk of the Seri diet. They augmented this with plants from the desert, including cactus fruit and seeds from mesquite or ironwood trees. The Seri would grind up the tree seeds and form a kind of gruel or mush with water. Later they would make a type of flatbread from this seed dough, fried in animal fat like the typical Indian frybread served at every modern-day North American powwow. The Seris have long since made an alcoholic drink out of the fruit of the pitahaya cactus, and still drink this special beverage during festivals and family celebrations. Since the early 20th Century overfishing in the Sea of Cortez has depleting many of the marine resources the Seris have relied on throughout their history. These people, who were once completely reliant on the abundance of Nature to provide for them have since adopted the standard Mexican diet which has brought a variety of health issues to the community, including obesity and related conditions such as diabetes. Tribal elders claim that drinking cactus juice can cure diabetes, but this has not been evaluated by Mexican health officials or anyone else.

Because the territory of the Seris is considered harsh by outsiders and has also been seen as having little economic value, these people were almost completely left alone until the last few decades of the 1800s. With most of their ancestral culture still intact, the Seris attracted attention of anthropologists, specifically from France and the United States, who were interested in studying one of the last untouched indigenous societies in Mexico. Researchers found a matriarchal culture with bloodlines recognized through female heads of families, although authority in most matters was vested in men. Women raised children, tended to the home, gathered materials from the desert, and made baskets, while men were responsible for fishing and what little game hunting could be had inland. Linguists at the beginning of the 20th Century also rushed to the area to study the unique Seri language, compiling grammars and vocabulary lists before it was too late. Books and articles written about the Seris from this time got the attention of the national government in faraway Mexico City. In the 1920s and 1930s the Mexican government sent educators and health professionals to try to force the Seris to integrate into the broader Mexican mestizo society. Until that time the Seris had roamed up and down the coast and into the desert making temporary encampments to follow seasonal resources. The Mexican government wanted all the Seri people settled, so they had them live in two primary towns. They also set up tribal councils and a local government structure that was altogether alien to this previously autonomous and self-sustaining people. While the Seri children learned Spanish in school, the Seri language remained strong. Because of the various outside influences and many rapid disruptions to the Seri way of life, by the early 1930s there were only a few hundred Seris left. For a time, many believed that the whole tribe would only last as an intact people for one or two more generations. In the end, the Seris proved the doubters wrong, as their population adapted to the encroaching modern world and rebounded, carrying their culture with them well into the future.

Because the territory of the Seris is considered harsh by outsiders and has also been seen as having little economic value, these people were almost completely left alone until the last few decades of the 1800s. With most of their ancestral culture still intact, the Seris attracted attention of anthropologists, specifically from France and the United States, who were interested in studying one of the last untouched indigenous societies in Mexico. Researchers found a matriarchal culture with bloodlines recognized through female heads of families, although authority in most matters was vested in men. Women raised children, tended to the home, gathered materials from the desert, and made baskets, while men were responsible for fishing and what little game hunting could be had inland. Linguists at the beginning of the 20th Century also rushed to the area to study the unique Seri language, compiling grammars and vocabulary lists before it was too late. Books and articles written about the Seris from this time got the attention of the national government in faraway Mexico City. In the 1920s and 1930s the Mexican government sent educators and health professionals to try to force the Seris to integrate into the broader Mexican mestizo society. Until that time the Seris had roamed up and down the coast and into the desert making temporary encampments to follow seasonal resources. The Mexican government wanted all the Seri people settled, so they had them live in two primary towns. They also set up tribal councils and a local government structure that was altogether alien to this previously autonomous and self-sustaining people. While the Seri children learned Spanish in school, the Seri language remained strong. Because of the various outside influences and many rapid disruptions to the Seri way of life, by the early 1930s there were only a few hundred Seris left. For a time, many believed that the whole tribe would only last as an intact people for one or two more generations. In the end, the Seris proved the doubters wrong, as their population adapted to the encroaching modern world and rebounded, carrying their culture with them well into the future.

Besides the holidays on the Catholic calendar and some Mexican civic holidays observed by modern-day Seris, the most important celebration for the tribe revolves around the Seri new year. To anyone who has lived in the desert, the beginning of rainy season causes everyone to sigh a collective sigh of relief and is a reason for great rejoicing. The Seri people are no exception. In the Sonora Desert the monsoon season begins in early July, so the Seris celebrate their new year on July First. The festivities begin on June 30th and last for a few days. These festivities include music and dancing, ample food and plenty of jugs of the notorious Seri pitahaya cactus wine. The Seris build lean-to-like shade structures on the beach as reminders of their ancestral encampments. They also paint their faces in ceremony for good luck in the new year and to ward off evil spirits. Characteristic Seri face painting usually consists of a line drawn across the face under the eyes and below that line intricate geometrical patterns or blocks of various colors. Outsiders are welcome for the new year’s celebrations and tourists are encouraged to visit. During this time, many people in the Seri villages make a nice portion of their annual income from craft sales to tourists.

The craft industry was a must to fill in the gap of income lost from the dwindling supply of fish from the Sea of Cortez. The Seri people are known for their basket weaving and carvings of figurines made from desert ironwood. Basket weaving dates back to time immemorial. Legend has it that the first Seri basket maker was a man and when he was about to die, he taught his craft to a teenage girl, and ever since then the making of baskets has been the exclusive realm of women. Baskets are made from the bark of young desert trees that crafters strip and fashion into vessels of striking beauty. Some elaborate baskets may take months to create. While basket weaving has always been a part of Seri culture, ironwood carving has a definite modern starting date: the year 1963. Seri villager José Astorga had a quarrel with his wife one day and went wandering in the desert to clear his head. He rested underneath a large ironwood tree and somewhere in the twilight of dozing off, José heard a soft but strong male voice say this to him:

“Make good use of this tree. Make figures out of the wood of this tree. Sell the figures and support your family with the money you will earn.”

The voice, wherever it came from, came at a time when the local economy in Seriland was particularly depressed. José gathered some wood and took it home. He broke out a machete and started hacking away at the wood. Over the course of the next few days, he would fashion birds, turtles and other animals out of this incredibly hard wood. His daughter Aurora started to carve, too, and then other people in the village followed suit. Over time the carving and polishing processes have been perfected and the gathering of desert ironwood has become a common practice for the Seris, almost like a modern-day throwback to their not-so-distant hunter-gatherer past. Non-Seris in the area have since made knock-offs of the Seri carvings, but the income generated by this recently invented craft has made a world of difference to the Seris who have struggled economically ever since they were thrust into the modern world against their will.

The voice, wherever it came from, came at a time when the local economy in Seriland was particularly depressed. José gathered some wood and took it home. He broke out a machete and started hacking away at the wood. Over the course of the next few days, he would fashion birds, turtles and other animals out of this incredibly hard wood. His daughter Aurora started to carve, too, and then other people in the village followed suit. Over time the carving and polishing processes have been perfected and the gathering of desert ironwood has become a common practice for the Seris, almost like a modern-day throwback to their not-so-distant hunter-gatherer past. Non-Seris in the area have since made knock-offs of the Seri carvings, but the income generated by this recently invented craft has made a world of difference to the Seris who have struggled economically ever since they were thrust into the modern world against their will.

Today, schools in the two Seri towns teach in both the Spanish and Seri languages. The United Nations has proclaimed the Seri language “vulnerable” which means it still has children speaking the language, but not so much outside the home. Local leaders and the Mexican central government are confident that recent efforts to preserve Seri language and culture will allow one of the last indigenous groups faced with assimilation to continue their ancestral traditions for many generations to come.

REFERENCES

Coolidge, Dane and Mary Roberts. The Last of the Seris. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1939. We are an Amazon affiliate. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2QdpN7q

BUY DESERT IRONWOOD CARVINGS HERE AND HELP SUPPORT THIS PODCAST: https://www.ebay.com/str/suenosimports/Ironwood-Carvings/_i.html?_storecat=2340362010

One thought on “Seri People, The Last to Assimilate”

My wife and I spent a fair amount of time as a guest of Becky Moser at the Seri village at El Desemboque. Becky was a missionary. She spent most of life with the Seri teaching the Seri. Beck produced a Seri dictionary from Seri to Spanish and English . I last visited Becky in 1992. The Seri loved Becky dearly. The Seri are an amazing people. Raul was my guide and friend.