Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In a lecture before the American Geographical Society in January of 1873, a bearded French-American by the name of Augustus Le Plongeon outlined his plans for an expedition to the Yucatán. The title of the lecture was “Vestiges of Antiquity: On the Coincidences between the Monuments of Ancient America and Those of Assyria and Egypt.” Le Plongeon, who had 8 years’ experience in Peru studying ancient monuments there, wanted to expand his study to Mexico and build on the work of Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, a French abbot who spent many years in Mexico as a missionary and studied its ancient past. Abbot de Bourbourg had theories connecting the Old World to the New via Plato’s lost continent of Atlantis and even suggested that the ancient civilizations in Mexico pre-date those of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Le Plongeon was to employ the latest technology to previously unexplored ruins of Mexico, specifically the Maya area, including new photography techniques and plaster casting. He raised the required money and arrived in the Yucatán with his new wife Alice in the summer of 1873.

In a lecture before the American Geographical Society in January of 1873, a bearded French-American by the name of Augustus Le Plongeon outlined his plans for an expedition to the Yucatán. The title of the lecture was “Vestiges of Antiquity: On the Coincidences between the Monuments of Ancient America and Those of Assyria and Egypt.” Le Plongeon, who had 8 years’ experience in Peru studying ancient monuments there, wanted to expand his study to Mexico and build on the work of Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, a French abbot who spent many years in Mexico as a missionary and studied its ancient past. Abbot de Bourbourg had theories connecting the Old World to the New via Plato’s lost continent of Atlantis and even suggested that the ancient civilizations in Mexico pre-date those of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Le Plongeon was to employ the latest technology to previously unexplored ruins of Mexico, specifically the Maya area, including new photography techniques and plaster casting. He raised the required money and arrived in the Yucatán with his new wife Alice in the summer of 1873.

Le Plongeon had somewhat of a blank slate to work with. Archaeology as a science was in its infancy and there were many theories – ranging from the well-thought-out to the bizarre – to explain the magnificent, extensive, and mostly unexcavated ruins found in the Mexican jungles. Since the early part of the 19th Century, Americans had looked south to those ruins and speculated about the history of their own part of North America. Many Americans at the time had a historical inferiority complex of sorts; as a young nation they wanted so desperately to be on par with the Old World and to have a sense of connection to a meaningful ancient past. As early as the 1820s Americans had theories connecting ancient Mexico to the ancient civilizations of the Old World and through proximity, the United States itself thus had a glorious ancient past. Modern-day archaeologists would say that the connection between, say, upstate New York and the world of the ancient Maya would be extremely tenuous or utterly nonexistent. The blank slate afforded to the various theorists, amateur antiquarians and low-grade religious leaders of the 19th Century gave them a wonderful world to explore and an empty vessel to fill with whatever suited their whims and agendas.

The story of the lost continent of Mu and its connection to ancient Mexico begins with a love affair. In 1871 while Augustus Le Plongeon was in London to study ancient Mesoamerican manuscripts at the British Museum, he met Alice Dixon. Alice, who was 25 years younger than Le Plongeon, was the daughter of famous British photographer Henry Dixon, who is known for his pioneering work in advanced photographic methods, including the panchromatic technique. Alice was her father’s assistant in his London studio and knew everything there was to know about photography. While her knowledge of photography interested Le Plongeon, his knowledge of ancient cultures interested Alice. After working closely together, Augustus Le Plongeon asked Alice Dixon to marry him and then they were off to the Yucatán before making a stop in New York.

The story of the lost continent of Mu and its connection to ancient Mexico begins with a love affair. In 1871 while Augustus Le Plongeon was in London to study ancient Mesoamerican manuscripts at the British Museum, he met Alice Dixon. Alice, who was 25 years younger than Le Plongeon, was the daughter of famous British photographer Henry Dixon, who is known for his pioneering work in advanced photographic methods, including the panchromatic technique. Alice was her father’s assistant in his London studio and knew everything there was to know about photography. While her knowledge of photography interested Le Plongeon, his knowledge of ancient cultures interested Alice. After working closely together, Augustus Le Plongeon asked Alice Dixon to marry him and then they were off to the Yucatán before making a stop in New York.

When the Le Plongeons arrived in Mérida, the capital of the Yucatán, the region was embroiled in the Caste War, the decades-long struggle of the indigenous Maya against the central government in Mexico City and the local non-indigenous landowners. For background on the conflict, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode Number 70 titled “The Mayan Cult of the Talking Cross.” The new American arrivals were unique among previous foreign archaeologists in the region because they took the time to learn the local Yucatec Maya language and became well versed in the politics and contemporary culture of the region. Their unique, almost holistic approach to their archaeological project opened doors for them and made their stay in the Yucatán go more smoothly. Both Augustus and Alice were accepted by the rebel group, the Santa Cruz Maya, which had control over most of the eastern Yucatán and thus the major ruined sites, and the two archaeologists moved freely in rebel-occupied territory. The focus of the Le Plongeons’ research and exploration would be at Chichén Itzá, which is now one of the most visited archaeological sites in all of Mexico, with its impressive structures such as its main pyramid, the Temple of Kukulkán. In the mid-1870s, at the time of Augustus and Alice’s arrival, the city was completely covered in jungle.

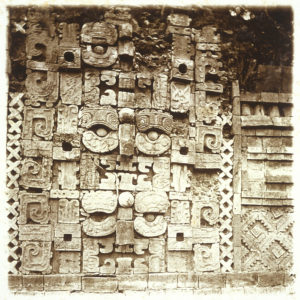

From the time he first set foot in Chichén Itzá, Augustus Le Plongeon sought to prove diffusion theories and to make the case that Maya civilization was not only old but it was the oldest on earth and the mother of many other world civilizations. Le Plongeon’s interpretation of what he saw and found at Chichén Itzá has been called by some authors as “inventive.” He had that “blank slate” previously mentioned, and could fill it with whatever he wanted, sometimes bending the physical archaeological record accordingly. One of Le Plongeon’s first “inventive” interpretation of what he saw at Chichén Itzá had to do with a Maya rope design he saw as part of a temple’s frontal carvings. He declared that the Maya had an ancient telegraph system that spanned the globe and connected it to other civilizations and colonies it had throughout the world. One of the biggest licenses he took with what he was uncovering was when he discovered a series of wall carvings on El Castillo, also now known as the Temple of Kukulcán. Not only did Le Plongeon claim that one of the portraits of the warriors on the temple looked like him, he claimed that he was the reincarnation of that warrior, and that he had actually lived at Chichén Itzá in its heyday as one of its rulers. He communicated his beliefs, or assertions, to the Maya crew working with him and they believed him. He did have a strange knack for finding important artifacts, everyone would agree, and so maybe, some thought, there was truth to what he was saying. He and his wife Alice would pioneer a new pseudoscientific field while in Mexico, that of “psychic archaeology.” They came upon major artifacts, they claimed, by using a unique blend of supposed psychic abilities, intuition, and channeling spirits to help them with their finds. In London, Alice Le Plongeon had been very involved in seances, mesmerism and studying the occult. As they wrote about their finds and published them in newspapers and magazines in America, the work of the Le Plongeons gained the attention of then-New-York-based Russian mystic and occultist Madame Helena Blavatsky. Blavatsy took some of the Le Plongeon Mexican research and incorporated it into her new theosophical movement. In her public writings Blavatsky hailed Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon as pioneers in, as she put it, “metaphysical archaeology.” While being celebrated among the mystical circles in New York and London, the Le Plongeons had less and less support from mainstream academic and antiquarian publications and institutions. While they seemed to have a special skill for finding impressive artifacts, the Le Plongeons were the first to do major excavations at sites such as Chichén Itzá and Uxmal, and because of this there were plenty of things for them to find at every turn. Both Augustus and Alice kept up the mystical and occult angle and continued crafting their tenuous pre-history of the New World in spite of serious objections and doubts of those taking a more mainstream view of antiquity.

From the time he first set foot in Chichén Itzá, Augustus Le Plongeon sought to prove diffusion theories and to make the case that Maya civilization was not only old but it was the oldest on earth and the mother of many other world civilizations. Le Plongeon’s interpretation of what he saw and found at Chichén Itzá has been called by some authors as “inventive.” He had that “blank slate” previously mentioned, and could fill it with whatever he wanted, sometimes bending the physical archaeological record accordingly. One of Le Plongeon’s first “inventive” interpretation of what he saw at Chichén Itzá had to do with a Maya rope design he saw as part of a temple’s frontal carvings. He declared that the Maya had an ancient telegraph system that spanned the globe and connected it to other civilizations and colonies it had throughout the world. One of the biggest licenses he took with what he was uncovering was when he discovered a series of wall carvings on El Castillo, also now known as the Temple of Kukulcán. Not only did Le Plongeon claim that one of the portraits of the warriors on the temple looked like him, he claimed that he was the reincarnation of that warrior, and that he had actually lived at Chichén Itzá in its heyday as one of its rulers. He communicated his beliefs, or assertions, to the Maya crew working with him and they believed him. He did have a strange knack for finding important artifacts, everyone would agree, and so maybe, some thought, there was truth to what he was saying. He and his wife Alice would pioneer a new pseudoscientific field while in Mexico, that of “psychic archaeology.” They came upon major artifacts, they claimed, by using a unique blend of supposed psychic abilities, intuition, and channeling spirits to help them with their finds. In London, Alice Le Plongeon had been very involved in seances, mesmerism and studying the occult. As they wrote about their finds and published them in newspapers and magazines in America, the work of the Le Plongeons gained the attention of then-New-York-based Russian mystic and occultist Madame Helena Blavatsky. Blavatsy took some of the Le Plongeon Mexican research and incorporated it into her new theosophical movement. In her public writings Blavatsky hailed Augustus and Alice Le Plongeon as pioneers in, as she put it, “metaphysical archaeology.” While being celebrated among the mystical circles in New York and London, the Le Plongeons had less and less support from mainstream academic and antiquarian publications and institutions. While they seemed to have a special skill for finding impressive artifacts, the Le Plongeons were the first to do major excavations at sites such as Chichén Itzá and Uxmal, and because of this there were plenty of things for them to find at every turn. Both Augustus and Alice kept up the mystical and occult angle and continued crafting their tenuous pre-history of the New World in spite of serious objections and doubts of those taking a more mainstream view of antiquity.

A big turning point in the research of the Le Plongeons occurred when Augustus found, by psychic means, of course, a large reclining stone figure, 7 meters underground, which he called a Chac Mool, a name meaning “red or great jaguar paw” in Yucatec Maya. He immediately declared that Chac Mool had been a ruler of Chichén Itzá and he had seen this ruler depicted throughout the ruins on stone carvings and in murals. Le Plongeon tried to spirit the statue out of Mexico to get it to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in the United States but was thwarted by government officials who apprehended the Chac Mool and took it to Mexico City. There, it was exhibited as one of the most important finds of the century and part of the Mexican patrimony that would never leave the country. Although Le Plongeon’s plans were snuffed out, he continued to weave the ancient story of this mythical ruler Chac Mool who was also known as Prince Coh. Chac Mool was the brother of Prince Aac, the evil lord of Uxmal. Prince Aac defeated Chac Mool in mortal combat and Chac Mool’s widow came to rule the kingdom as Queen Móo. The territory of Chichén Itzá and its surroundings became known as the Kingdom of Móo. Queen Móo was then forced to marry her evil brother-in-law Prince Aac, at which point she fled to Egypt where she was revered as the goddess Isis. She also brought with her a complex civilization with its origins in Mexico. One of Queen Móo’s last acts in the Americas, Le Plongeon explained, was to commission a stone carving dedicated to her husband in the form of the Chac Mool statue. With a further elaboration of the ancient Maya/ancient Egypt connection came an even more fantastic claim regarding Queen Móo. She had returned to the Yucatán 115 generations later reincarnated as none other than Alice Le Plongeon. While accepted by people such as the members of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society, very few serious scholars took the work of the Le Plongeons seriously after the Queen Móo-Isis-Alice connection. This didn’t stop the Le Plongeons and their discoveries and their interpretations kept coming.

A big turning point in the research of the Le Plongeons occurred when Augustus found, by psychic means, of course, a large reclining stone figure, 7 meters underground, which he called a Chac Mool, a name meaning “red or great jaguar paw” in Yucatec Maya. He immediately declared that Chac Mool had been a ruler of Chichén Itzá and he had seen this ruler depicted throughout the ruins on stone carvings and in murals. Le Plongeon tried to spirit the statue out of Mexico to get it to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in the United States but was thwarted by government officials who apprehended the Chac Mool and took it to Mexico City. There, it was exhibited as one of the most important finds of the century and part of the Mexican patrimony that would never leave the country. Although Le Plongeon’s plans were snuffed out, he continued to weave the ancient story of this mythical ruler Chac Mool who was also known as Prince Coh. Chac Mool was the brother of Prince Aac, the evil lord of Uxmal. Prince Aac defeated Chac Mool in mortal combat and Chac Mool’s widow came to rule the kingdom as Queen Móo. The territory of Chichén Itzá and its surroundings became known as the Kingdom of Móo. Queen Móo was then forced to marry her evil brother-in-law Prince Aac, at which point she fled to Egypt where she was revered as the goddess Isis. She also brought with her a complex civilization with its origins in Mexico. One of Queen Móo’s last acts in the Americas, Le Plongeon explained, was to commission a stone carving dedicated to her husband in the form of the Chac Mool statue. With a further elaboration of the ancient Maya/ancient Egypt connection came an even more fantastic claim regarding Queen Móo. She had returned to the Yucatán 115 generations later reincarnated as none other than Alice Le Plongeon. While accepted by people such as the members of Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society, very few serious scholars took the work of the Le Plongeons seriously after the Queen Móo-Isis-Alice connection. This didn’t stop the Le Plongeons and their discoveries and their interpretations kept coming.

In addition to claiming the connection to Egypt through Isis, Augustus Le Plongeon claimed to have discovered stone tablets in Chichén Itzá showing details of ancient Maya rites of Freemasonry. As a high-ranking Freemason himself, Le Plongeon was eager to point out masonic signs and symbols in the ruins throughout the Yucatán. He claimed that the triangular arches, numbers of temple steps and carved figures seeming to wear “masonic aprons” indicated that the ancient Mexicans had knowledge of Freemasonry’s Sacred Mysteries and that these masonic rites and mysteries originated in the New World, not the old. It was Queen Móo as Isis who transferred this arcane knowledge to Egypt. This assertion was a point of pride for Augustus Le Plongeon, because it seemed to give more legitimacy to American freemason lodges. America could thus shed some of its inferiority complex if it could claim such ancient roots to Freemasonry, which was very popular in the United States at the end of the 19th Century.

By the time Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon returned to the United States in 1880, their finds and stories had been published far and wide and received either severe criticism or high praise. Their photographs and plaster castings along with detailed notes to accompany them are still regarded to this day as important pieces of documentation of the ancient Mexican archaeological record. The various stories and fabricated histories were thoroughly dismissed by scholars, although they did get some traction with the public. After returning to America Augustus Le Plongeon published 3 books about the Kingdom of Móo, the Mexican “mother civilization” and its connection to other ancient cultures. The first, in 1880, was called Vestiges of the Mayas, or, Facts Tending to Prove That Communications and Intimate Relations Must Have Existed, in Very Remote Times, between the Inhabitants of Mayab and Those of Asia and Africa. His second book, with another very long title, was printed in 1886 and titled Sacred Mysteries among the Mayas and the Quichés 11,500 Years Ago: Their Relation to the Sacred Mysteries of Egypt, Greece, Chaldea, and India; or Free Masonry in Times Anterior to the Temple of Solomon. His last book, published with his own resources in 1896, was titled Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx.

By the time Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon returned to the United States in 1880, their finds and stories had been published far and wide and received either severe criticism or high praise. Their photographs and plaster castings along with detailed notes to accompany them are still regarded to this day as important pieces of documentation of the ancient Mexican archaeological record. The various stories and fabricated histories were thoroughly dismissed by scholars, although they did get some traction with the public. After returning to America Augustus Le Plongeon published 3 books about the Kingdom of Móo, the Mexican “mother civilization” and its connection to other ancient cultures. The first, in 1880, was called Vestiges of the Mayas, or, Facts Tending to Prove That Communications and Intimate Relations Must Have Existed, in Very Remote Times, between the Inhabitants of Mayab and Those of Asia and Africa. His second book, with another very long title, was printed in 1886 and titled Sacred Mysteries among the Mayas and the Quichés 11,500 Years Ago: Their Relation to the Sacred Mysteries of Egypt, Greece, Chaldea, and India; or Free Masonry in Times Anterior to the Temple of Solomon. His last book, published with his own resources in 1896, was titled Queen Móo and the Egyptian Sphinx.

In Le Plongeon’s later works he tied Queen Móo’s kingdom to the lost continent of Atlantis. Were the Kingdom of Móo and the pre-Egyptian super civilization one in the same? We would see the “histories” of ancient Mexico created by Augustus Le Plongeon develop into something altogether different after his papers and notes were passed to a man named James Churchward by the recently widowed Alice Le Plongeon in 1911. Churchward “repackaged” the histories and elaborated on them in three books released in 1926, 1931 and 1936 respectively. These books were titled The Lost Continent of Mu, The Children of Mu, and The Cosmic Forces of Mu. In Churchward’s works the kingdom of Queen Móo had not only morphed into its own continent but it moved out of Mexico and to somewhere in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Maps today show this supposed lost continent and even artifacts to go along with it, but few today realize that the stories of the Pacific Ocean’s own lost continent began with a lone archaeologist and his wife toiling away in the jungles of 19th Century Mexico. Like so many things in the paranormal and fringe research communities, the Lost Continent of Mu snowballed, took some interesting turns and took on a life of its own. Whether or not the original story is based on a real intuitive or “psychic” reconstruction of history or is just a bunch of mumbo jumbo is up to the investigator to decide.

REFERENCES

Evans, R. Tripp. Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination 1820-1915. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

5 thoughts on “The Lost Continent of Mu & the Mexican Mother Civilization”

We wholly and completely misunderstand Earth and human history because of geology’s “no worldwide flood” paradigm, which is about 200 years old. Adam Sedgwick is mostly responsible for the belief as he had set about Europe in the early 1800s in search of flood remnants. He could not find them. Thus, no flood. In his 1831 address to the Geo Soc of London, he recanted his belief in a worldwide flood – big news because he was not only the society’s president, but he was also a Cambridge prof and an ordained minister in the Church of England. The belief persists to the present and affects modern thought. Unfortunately, his conclusion was incorrect. From the evidence, the conclusion should have been: presently exposed landscapes were never submerged in a common flood. This is an indisputably true statement, but it is vastly different from the claim that there was never a worldwide flood. Sedgwick mistakenly passed judgment onlandscapes that he could not observe – there’s quite a bit of water out there, no?! (BTW – the history of the prevailing “no flood, ever” paradigm is unknown to nearly all PhDs in geology.) But now Google Maps/Earth allow us to see into the depths, and we observe submerged river drainage systems beneath more than 2 miles of water…. The introduction of such a vast amount of water would be memorable, no? (Explains flood stories in cultures from around the planet.) Must have been introduced quickly so as to preserve the drainages. How? When? All explained in various posts here: https://theworldwideflood.com

there are a lot of evidence on the flood, but in my research, the Velkovsky-material AND the logical ETexplanations on this from the “Erra-ET-team”- brings much of this into a logical light.

http://galactic.to/rune/Sem_Vel2.html

http://galactic.to/rune/destroyercometorigin.htm

A related follow-on: a discussion of Atlantis and its fate can be found here https://theworldwideflood.com/2018/01/10/expedition-atlantis/

Interesting! I was always enchanted with Chac Mool. I climbed the pyramid in Chichen Itza to see it at the top and take a picture. It was long before the “selfie” days, and I was alone at the top of the pyramid, so the picture is only Chac Mool…and does not include me. Then had to figure out how to climb down! Not an easy task! No one in my group knew where I was…left alone at the top with Chac Mool! Great memories!

Sweet! Thanks for stopping by and commenting.