Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1534. The scraggly band of what remained of the crew from the Spanish ship Concepción entered Mexico City asking to meet with Hernán Cortés, the famous conquistador who had become ennobled by the Spanish king and had been granted complete authority of New Spain. Cortés met with the men immediately. Almost immediately, a member of the crew opened up a small cloth bag and poured out its contents: black pearls as big as grapes. The crew had many stories to tell, starting with the departure of the Concepción from the port of Manzanillo on November 30 of 1533.

The year was 1534. The scraggly band of what remained of the crew from the Spanish ship Concepción entered Mexico City asking to meet with Hernán Cortés, the famous conquistador who had become ennobled by the Spanish king and had been granted complete authority of New Spain. Cortés met with the men immediately. Almost immediately, a member of the crew opened up a small cloth bag and poured out its contents: black pearls as big as grapes. The crew had many stories to tell, starting with the departure of the Concepción from the port of Manzanillo on November 30 of 1533.

Cortés had dispatched the ship, under command of Diego de Becerra, to head up the Pacific coast of modern-day Mexico to look for a group of ships sent north the previous year. The previous year’s expedition, which was declared lost, was looking for two rumored pieces of geography. One was the Strait of Anián, the western Pacific outlet of the Northwest Passage that would connect the Atlantic with the Pacific. The other was the fabled Island of California, a rich land ruled by black women first talked about in the 1510 book Las sergas de Esplandián – “The Adventures of Esplandián” – by Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo, a romance novelist popular in Spain. While plying the waters of the Gulf of California – also known as the Sea of Cortez – the pilot of the Concepción, Fortún Ximénez, took over the ship,  killed the captain, and landed near present day La Paz, Baja California. Ximénez is credited as being the first European to ever land on the Baja Peninsula and he named it California because he was certain he had made it to the fabled island in the Montalvo book. His time there was short lived. While trying to subjugate the Indians, Ximénez was killed, and the remaining crew decided to return to Mexico City.

killed the captain, and landed near present day La Paz, Baja California. Ximénez is credited as being the first European to ever land on the Baja Peninsula and he named it California because he was certain he had made it to the fabled island in the Montalvo book. His time there was short lived. While trying to subjugate the Indians, Ximénez was killed, and the remaining crew decided to return to Mexico City.

Perhaps partly influenced by the romance novels of Montalvo but more curious about the large black pearls before him, the powerful Cortés decided to lead an expedition to the fabled Island of California himself, and to do there what he knew how to do best: conquer the kingdom of the black queen, subjugate her people and extract the riches in the name of the Crown. Cortés’ expedition never found the Amazon Queen Calafia’s Kingdom of California, and besides starting a few pearl fisheries at the tip of the peninsula, the aging conquistador found little of commercial value in Baja. He named what he still thought was an island Santa Cruz. Interest in the region declined thereafter and it became a remote colonial backwater of the Spanish Empire.

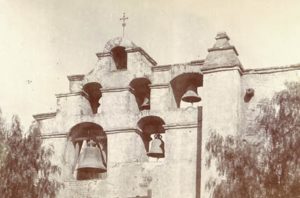

The first post-Cortés attempt to colonize Baja was made almost 150 years later in 1683. The Spanish government sent a group of 200 men to settle an area near Cortés’ failed pearl fisheries at La Paz on the southern tip of the peninsula. The settlement could not resist the attacks of the natives and was abandoned. Europeans would return permanently near the end of the next decade. In October of 1697 Jesuit priest Juan María de Salvatierra established the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó and the settlement became the administrative center of the territory known as Las Californias. In the beginning, because of the harsh desert climate and inhospitable terrain of most of the peninsula, the early years required help from across the Gulf of California. Over the course of the next 70 years the Jesuits established 17 missions and several sub-missions called visitas up and down the Peninsula of Baja California which all eventually became self-sustaining. The central authority in Mexico City was very far away and for seven decades the Jesuits were left to their own devices, effectively ruling the region as a separate Jesuit political entity.

The first post-Cortés attempt to colonize Baja was made almost 150 years later in 1683. The Spanish government sent a group of 200 men to settle an area near Cortés’ failed pearl fisheries at La Paz on the southern tip of the peninsula. The settlement could not resist the attacks of the natives and was abandoned. Europeans would return permanently near the end of the next decade. In October of 1697 Jesuit priest Juan María de Salvatierra established the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó and the settlement became the administrative center of the territory known as Las Californias. In the beginning, because of the harsh desert climate and inhospitable terrain of most of the peninsula, the early years required help from across the Gulf of California. Over the course of the next 70 years the Jesuits established 17 missions and several sub-missions called visitas up and down the Peninsula of Baja California which all eventually became self-sustaining. The central authority in Mexico City was very far away and for seven decades the Jesuits were left to their own devices, effectively ruling the region as a separate Jesuit political entity.

The rumors of wealth in this faraway place started up again during the time of the Jesuits. Because the Jesuits controlled nearly every aspect of life in Baja, no outsider was permitted to verify the extent of the Jesuits’ wealth. Stories began to circulate about secret gold and silver mines that went back to pre-Hispanic times. Some say that even some of the gold from the Aztec Empire came from this region of Mexico. By the 1700s Russian and English fur traders and whalers had been harboring in the coves of Baja and trading with the missions. For basic foodstuffs such as beef, fresh vegetables and fruits, the Jesuits obtained items from the rich cargoes of the ships, including gold coin. In addition to regular commercial vessels, Baja’s quiet waters and secluded bays saw pirate ships. The English and Dutch buccaneers traded pirate booty for the essentials, thus increasing the wealth of the Jesuits. People outside the region began questioning whether or not the main reason for the Jesuits being in Baja was not to save souls but to get rich.

The rumors of wealth in this faraway place started up again during the time of the Jesuits. Because the Jesuits controlled nearly every aspect of life in Baja, no outsider was permitted to verify the extent of the Jesuits’ wealth. Stories began to circulate about secret gold and silver mines that went back to pre-Hispanic times. Some say that even some of the gold from the Aztec Empire came from this region of Mexico. By the 1700s Russian and English fur traders and whalers had been harboring in the coves of Baja and trading with the missions. For basic foodstuffs such as beef, fresh vegetables and fruits, the Jesuits obtained items from the rich cargoes of the ships, including gold coin. In addition to regular commercial vessels, Baja’s quiet waters and secluded bays saw pirate ships. The English and Dutch buccaneers traded pirate booty for the essentials, thus increasing the wealth of the Jesuits. People outside the region began questioning whether or not the main reason for the Jesuits being in Baja was not to save souls but to get rich.

A validation to the rumors happened sometime in the late 1750s. A ship whose cargo holds were full of gold, silver, precious stones, pearls and coral landed in the port of Cadiz, Spain. The cargo had come from the Jesuits of Baja and was delivered to a Venetian merchant. Word reached the royal court in Spain and later a representative of King Charles the Third, a man named José de Gálvez who was not a fan of the Jesuit Order, went to the missions of Baja to investigate. Coffers were empty and his conclusion was that the Jesuit fathers were living a meager existence in a very harsh land.

Gálvez didn’t find any evidence of extreme wealth because a confidential communication was sent from Rome to the mission at Loreto to warn the fathers of the coming examination by royal authorities. The fathers did their best to hide what they could and destroyed certain records that would incriminate them. After the royal visit, the Jesuits also must have felt their days were numbered in New Spain. They prepared themselves accordingly.

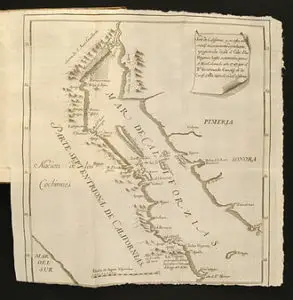

Ferdinand Konščak was a young Jesuit who was born in a small town in Croatia which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was educated in a variety of places and was well-versed in many subjects. The bright young Father Ferdinand was assigned to Baja California in 1732. He became the head of Mission San Ignacio in 1748 and the chief inspector of all the missions in 1758. Konščak’s many abilities included linguistics and cartography, and he conducted 3 expeditions to explore Baja in the years 1746, 1751 and 1753. He was able to communicate with all Indian groups on the peninsula and he was the first European to explore certain regions of Baja. Konščak proved once and for all that Baja California was not an island. His maps were so detailed and his knowledge of the region so complete that legends say that when word came from Rome of the impending expulsion of the Jesuits, he was in charge of the construction of the secret Mission of Santa Isabel in order to hide the order’s massive accumulation of wealth.

Ferdinand Konščak was a young Jesuit who was born in a small town in Croatia which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was educated in a variety of places and was well-versed in many subjects. The bright young Father Ferdinand was assigned to Baja California in 1732. He became the head of Mission San Ignacio in 1748 and the chief inspector of all the missions in 1758. Konščak’s many abilities included linguistics and cartography, and he conducted 3 expeditions to explore Baja in the years 1746, 1751 and 1753. He was able to communicate with all Indian groups on the peninsula and he was the first European to explore certain regions of Baja. Konščak proved once and for all that Baja California was not an island. His maps were so detailed and his knowledge of the region so complete that legends say that when word came from Rome of the impending expulsion of the Jesuits, he was in charge of the construction of the secret Mission of Santa Isabel in order to hide the order’s massive accumulation of wealth.

Santa Isabel, it is said, arose in a desert box canyon, on the Gulf of California side of the San Pedro Martir Mountains about halfway down the peninsula. It was made on the site of a mission that started to be built a decade before but was abandoned. Construction continued in secret over a few years. 270 burros laden with gold, silver, pearls, jewels and other valuables supposedly arrived at the secret mission and the precious items were stored underground or in caves near Mission Santa Isabel. There is also a legend from across the Gulf in the State of Sonora called “El Maldición de Isabel”, or “Isabel’s Curse,” that tells of missionaries who gathered up their gold from the western part of Mexico and with the help of 50 Yaqui Indians had it loaded all onto ships that set sail for the eastern shores of Baja. When the ship landed, 2 priests supervised the unloading of the treasure and accompanied it as it was taken overland to its final destination, an adobe structure near a steep cliff on the side of a canyon. One of the supervising priests put a curse on the Indians, telling them that if the story got out and people came looking for the treasure, they would die. Could this legend from Sonora be talking about the same secret Jesuit mission called Santa Isabel?

The axe finally fell on February 2, 1768 when King Charles the Third of Spain issued the Order of Expulsion that closed down all Jesuit operations in the New World. The Jesuits were prepared and when the order came, they caused a landslide in the front of the small canyon in which the secret mission was located, thus sealing it off from the outside world. They planted cacti in the trail leading to the canyon and destroyed all documents relating to Santa Isabel. As most treasure stories go, the Jesuits vowed to return, but they never did, and generations passed with only vague stories and pieces of stories to go by.

The axe finally fell on February 2, 1768 when King Charles the Third of Spain issued the Order of Expulsion that closed down all Jesuit operations in the New World. The Jesuits were prepared and when the order came, they caused a landslide in the front of the small canyon in which the secret mission was located, thus sealing it off from the outside world. They planted cacti in the trail leading to the canyon and destroyed all documents relating to Santa Isabel. As most treasure stories go, the Jesuits vowed to return, but they never did, and generations passed with only vague stories and pieces of stories to go by.

Interest in the lost Mission of Santa Isabel was rekindled in the 20th Century. Many adventurers have scoured the inhospitable terrain of the Baja Peninsula with this bit of information or that bit of information, hunting for the Jesuit riches. A mapmaker named Venegas created a chart of Baja in 1757 which shows a few references to Santa Isabel  that have kept treasure-hunters hopeful. On the Venegas map there is a “Santa Isabel Water Hole” that is located near the coast about one third down the peninsula. The “Santa Isabel Mountains” are located near modern-day San Felipe. Some legends connected with the lost mission mention certain geographical markers and so far all of the clues have led to wild goose chases. Gold mining operations are in full force in parts of Baja to this day, so it is not implausible that the Indians and the Jesuits both had very productive mines a few hundred years ago. We are left with an open-ended story. Of the many expeditions to find the Lost Mission of Santa Isabel, not one has come up with anything. Has the treasure already been extracted secretly? Did the Jesuit Order return to recover its massive wealth? Or is this just another gold-fever-inspiring tall tale to make foolish people wander in a desert?

that have kept treasure-hunters hopeful. On the Venegas map there is a “Santa Isabel Water Hole” that is located near the coast about one third down the peninsula. The “Santa Isabel Mountains” are located near modern-day San Felipe. Some legends connected with the lost mission mention certain geographical markers and so far all of the clues have led to wild goose chases. Gold mining operations are in full force in parts of Baja to this day, so it is not implausible that the Indians and the Jesuits both had very productive mines a few hundred years ago. We are left with an open-ended story. Of the many expeditions to find the Lost Mission of Santa Isabel, not one has come up with anything. Has the treasure already been extracted secretly? Did the Jesuit Order return to recover its massive wealth? Or is this just another gold-fever-inspiring tall tale to make foolish people wander in a desert?

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography):

Baja Legends by Greg Niemann

Baja California, Land of Missions by David Kier

The Old Missions of Baja and Alta California 1697-1834 by Max Kurillo

Baja California by Ralph Hancock

There it is: Baja! by Mike McMahan