Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

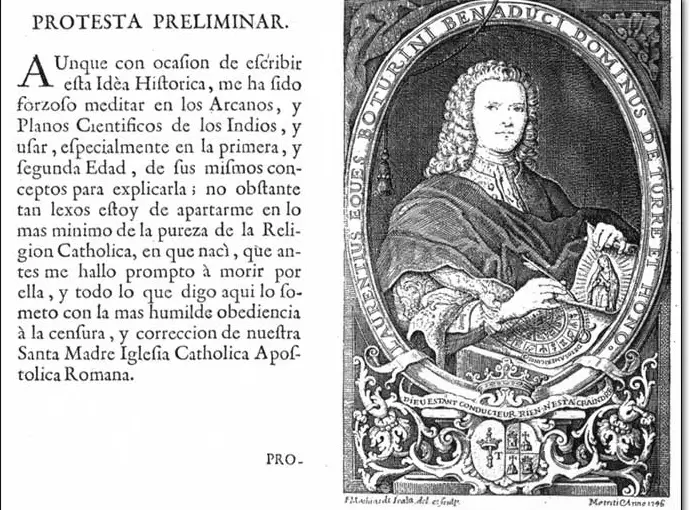

Our story of this mysterious indigenous map – now known as the Mapa Tlotzin – begins in Europe in the 1730s. Knight of the Holy Roman Empire and son of a minor Italian noble from Lombardy, Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci had to flee Vienna when the Austrians declared war on Spain. Boturini fled to England then to Portugal before ending up in Madrid. While in the Spanish capital the Italian met the Countess of Santibáñez who was the daughter of Teresa Francisca Nieto de Silva y Cisneros, a deceased Spanish noblewoman who had three titles: Marchioness of Tenebrón, Viscountess of Ilucán and Countess of Moctezuma. This last title indicated that the Countess of Santibáñez’ mother was a descendent of Aztec Emperor Montezuma the Second, whose successors had been ennobled by the king of Spain almost two centuries before Boturini arrived in Madrid. The Countess of Santibáñez, as a descendent of Emperor Montezuma through her mother, was due a lifetime pension from the treasury of New Spain in Mexico City that had ceased to arrive. The countess tasked Lorenzo Boturini with going to Mexico City to retrieve from the treasury what was rightfully due her as an heir of the Aztec emperors. Boturini arrived in New Spain in 1736.

Our story of this mysterious indigenous map – now known as the Mapa Tlotzin – begins in Europe in the 1730s. Knight of the Holy Roman Empire and son of a minor Italian noble from Lombardy, Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci had to flee Vienna when the Austrians declared war on Spain. Boturini fled to England then to Portugal before ending up in Madrid. While in the Spanish capital the Italian met the Countess of Santibáñez who was the daughter of Teresa Francisca Nieto de Silva y Cisneros, a deceased Spanish noblewoman who had three titles: Marchioness of Tenebrón, Viscountess of Ilucán and Countess of Moctezuma. This last title indicated that the Countess of Santibáñez’ mother was a descendent of Aztec Emperor Montezuma the Second, whose successors had been ennobled by the king of Spain almost two centuries before Boturini arrived in Madrid. The Countess of Santibáñez, as a descendent of Emperor Montezuma through her mother, was due a lifetime pension from the treasury of New Spain in Mexico City that had ceased to arrive. The countess tasked Lorenzo Boturini with going to Mexico City to retrieve from the treasury what was rightfully due her as an heir of the Aztec emperors. Boturini arrived in New Spain in 1736.

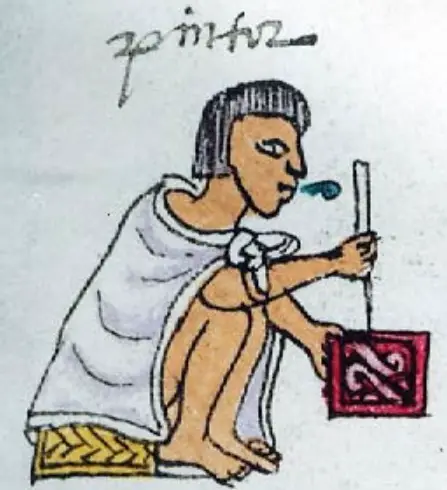

The initial task of securing an inheritance for the countess turned into an 8-year stay in New Spain for the Italian Boturini. While in Mexico he fell in love with the country’s history and cultures, even learning to speak Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire still very much in everyday use during colonial times. Boturini’s fascination with Mexican history led him to acquire many interesting manuscripts and paintings, some of them dating back to before the Spanish Conquest. In Boturini’s collection were many documents produced by the hands of tlacuilos, or indigenous scribes, from the collection of Juan de Alva Ixtlilxochitl. Alva Ixtlilxochitl was a direct descendent of the rulers of the ancient Kingdom of Texcoco, and he died a few decades before Boturini’s arrival in Mexico. Many of these documents came from the fabled Library of Texcoco, a repository of codices, maps, scrolls, illustrations, and other documents at the royal palace of Texcoco that may have numbered into the thousands. For more information about the central Mexican Kingdom of Texcoco, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 133 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/ Part of the Texcoco collection of Juan de Alva Ixtlilxochitl that came into Boturini’s possession was a curious map painted on a narrow strip of deer hide. This map would later be known as the Mapa Tlotzin and would end up in the National Library of France in Paris, where it remains to this day.

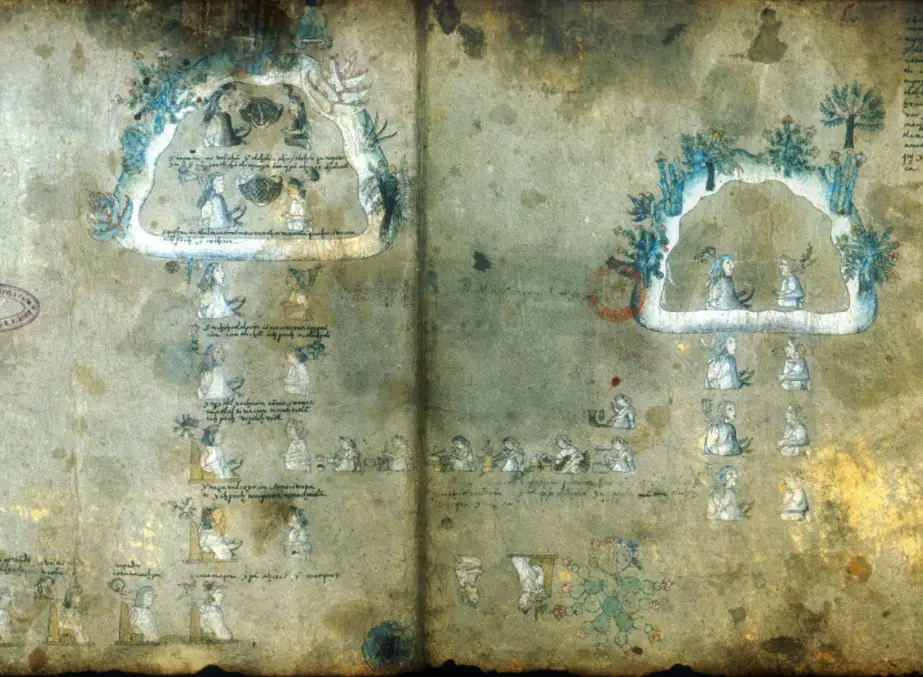

The Mapa Tlotzin is part map and part illustrated historical document. The creator or creators used a great deal of color when making this, much of which is still vibrant centuries later. For a brief overview and description of the piece, we can turn to a special edition of Arqueología Mexicana referencing ancient Mexican codices. The authors say this about the mapa:

“The story begins on the left margin with the first cave, which has a bat with open wings in the upper part and whose head was on the head of the characters who are inside it, and which gives its name to the place. : Zinacanóztoc (‘The Cave of the Bat’ in Nahuatl). Inside there appears a seated couple, in profile, and in the middle of it a small basket with a baby. This cave, like four others, has various plants on its edges that range from small and leafy trees to magueys, prickly pears and (other) cacti. Four Chichimec characters appear in the lower part of the cave, walking, in profile and facing to the right. Each one of them has their name written according to the indigenous pictographic writing, which allows us to read the names of two women: Malinalxóchitl and Cuauhcíhuatl, and two men: Amacuil and Tlotzin (the founder of the Texcoco dynasty), the latter with a bow and arrow. Evidently, the tlacuilo thus indicated the Chichimeca origin of each one. The women carry a basket slung over their shoulders; in one of them the head of a snake is visible and in the other, what appears to be the head of a rabbit.

“The story begins on the left margin with the first cave, which has a bat with open wings in the upper part and whose head was on the head of the characters who are inside it, and which gives its name to the place. : Zinacanóztoc (‘The Cave of the Bat’ in Nahuatl). Inside there appears a seated couple, in profile, and in the middle of it a small basket with a baby. This cave, like four others, has various plants on its edges that range from small and leafy trees to magueys, prickly pears and (other) cacti. Four Chichimec characters appear in the lower part of the cave, walking, in profile and facing to the right. Each one of them has their name written according to the indigenous pictographic writing, which allows us to read the names of two women: Malinalxóchitl and Cuauhcíhuatl, and two men: Amacuil and Tlotzin (the founder of the Texcoco dynasty), the latter with a bow and arrow. Evidently, the tlacuilo thus indicated the Chichimeca origin of each one. The women carry a basket slung over their shoulders; in one of them the head of a snake is visible and in the other, what appears to be the head of a rabbit.

Their outfits are made from animal skin. In the case of men, there is a crown of hay surrounding the head; they are warriors and specialized hunters. These characters are interspersed with elements of flora and fauna of unusual size, such as two deer, a rabbit and a snake, a reflection of indigenous symbolism and worldview. The second cave shelters six seated characters. Three of them are on the left, two men, Amácuil and Tlotzin, and a woman, Icpaxóchitl. Facing them are Malinalxóchitl, Nopaltzin and Cuauhcíhuatl. A tree in the upper left part provides the place name: Quauhyácac ( which means in Nahuatl, ‘At the Top of the Trees’). Under the gloss of this cave there is a drawing in black ink that completely breaks with the style of the rest of the document. It is, perhaps, of a dead character on a decorated base that was added at some unrecorded time in the original codex.”

What this elaborate painting is showing is an often-repeated theme on very early codices in central Mexico. The Mapa Tlotzin tells the tales of migration and the foundation of dynasties or noble houses from humble or more uncivilized Chichimeca roots, in a sort of ancient “rags to riches” fashion. The people emerging from the caves in this painted document illustrate genealogies of specific indigenous royal lines. In this case, the mapa emphasizes the dominance of the Kingdom of Texcoco in the Basin of Mexico Region. While no researcher can positively tell why this document was made or for whom, we in the 21st Century can deduce that the Mapa Tlotzin was probably produced to legitimize the position of the ruling elite at the time by showing their mythical historical origins. This piece was most likely created for the noble family itself, as there is a direct link to the noble family of Texcoco through Juan de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, who possessed the map in historical times. As it has some post-Conquest rulers of Texcoco painted on its surface, some researchers theorize that the Mapa Tlotzin may have been presented to Spanish authorities well after its creation date to indicate the noble lineage of those who survived the Conquest. It was quite common in New Spain that this sort of documentation – called by some researchers as “paintings” or “maps” – formed parts of litigation files, used by colonial legal authorities to determine land rights, taxation status or other ancestral privileges associated with the descendants of ancient indigenous royal families. The Mapa Tlotzin thus serves to highlight the vitality and importance of native societies and their elites well into the colonial period.

What this elaborate painting is showing is an often-repeated theme on very early codices in central Mexico. The Mapa Tlotzin tells the tales of migration and the foundation of dynasties or noble houses from humble or more uncivilized Chichimeca roots, in a sort of ancient “rags to riches” fashion. The people emerging from the caves in this painted document illustrate genealogies of specific indigenous royal lines. In this case, the mapa emphasizes the dominance of the Kingdom of Texcoco in the Basin of Mexico Region. While no researcher can positively tell why this document was made or for whom, we in the 21st Century can deduce that the Mapa Tlotzin was probably produced to legitimize the position of the ruling elite at the time by showing their mythical historical origins. This piece was most likely created for the noble family itself, as there is a direct link to the noble family of Texcoco through Juan de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, who possessed the map in historical times. As it has some post-Conquest rulers of Texcoco painted on its surface, some researchers theorize that the Mapa Tlotzin may have been presented to Spanish authorities well after its creation date to indicate the noble lineage of those who survived the Conquest. It was quite common in New Spain that this sort of documentation – called by some researchers as “paintings” or “maps” – formed parts of litigation files, used by colonial legal authorities to determine land rights, taxation status or other ancestral privileges associated with the descendants of ancient indigenous royal families. The Mapa Tlotzin thus serves to highlight the vitality and importance of native societies and their elites well into the colonial period.

Researchers have a difficult time dating the Mapa Tlotzin as there are layers of paint and it seems as if the document was a work in progress spanning possibly decades. As one researcher put it, the document, “seems to deny the Spanish presence.” It was thought to have been created in about 1550, a few decades after the Conquest but some art historians say that the Mapa Tlotzin is purely pre-Hispanic based on its layout and execution. The document relies heavily on pre-Conquest indigenous imagery and its narrative style closely matches with what experts call the “Texcoco School” of manuscript painting which flourished in the Kingdom of Texcoco in the late 1400s and early 1500s. As there are layers of paint on this unique deerskin creation, some researchers believe that this map may date as far back as the 1490s to a few decades before Europeans arrived in Mexico.

So, how did this beautiful and important ancient document end up in Paris? We must return to the story of the Italian nobleman Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci who acquired the Mapa Tlotzin for his ever-growing collection of pre-Hispanic Mexican documents, paintings, and other antiquities. For the 1740s, Boturini had the largest such collection amassed by any European. In his 8 years in New Spain, while he wasn’t trying to secure the Countess de Santibáñez’s inheritance, the Italian also undertook a deep investigation into the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe. He planned on writing a book about the Mexican Virgin and also intended to crown the image with a gold crown. Boturini began a fundraising effort to obtain the money to buy that gold crown. These very public activities of a foreigner raised suspicions from the colonial government in Mexico City. Boturini was arrested and accused of entering New Spain on official business without a special license from the Council of the Indies and for introducing papal documents without a royal permit. The Viceroy of New Spain, Pedro Cebrián y Agustin, the 5th Count of Fuenclara, imprisoned Boturini and impounded his collection. After spending 8 months in jail, Boturini was sent to Spain, but his collection – including the Mapa Tlotzin – remained in the office of the secretary of the viceroyalty in Mexico City. There, the collection was neglected and over time was subject to pilferage by bureaucrats. In Spain, Boturini was absolved of all wrongdoing by the Council of the Indies. The Spanish king was taken by the case and was impressed by the Italian nobleman’s knowledge and interest in this prized overseas possession. The king then made Boturini the official royal chronicler of the Indies and ordered that his collection be returned to him. The collection never was never restored to Boturini, including the famous painted map from Texcoco. With a new viceroy in Mexico City, the Boturini Collection was given to a historian named Mariano Fernández who, upon his death, passed it to Mexican anthropologist and astronomer Antonio de León y Gama. When he died in 1802 the Boturini Collection passed to his heirs who broke it up and sold off different pieces to various collectors. By 1889 the Mapa Tlotzin ended up in the hands of Eugene Goupil, a Mexican of French descent. When Goupil died in 1896, his widow donated the mapa and other ancient Mexican works to the National Library of France in Paris. There has been a movement to repatriate these documents and paintings to Mexico, but the French are loath to let go of such a valuable and historically important piece as the Mapa Tlotzin.

So, how did this beautiful and important ancient document end up in Paris? We must return to the story of the Italian nobleman Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci who acquired the Mapa Tlotzin for his ever-growing collection of pre-Hispanic Mexican documents, paintings, and other antiquities. For the 1740s, Boturini had the largest such collection amassed by any European. In his 8 years in New Spain, while he wasn’t trying to secure the Countess de Santibáñez’s inheritance, the Italian also undertook a deep investigation into the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe. He planned on writing a book about the Mexican Virgin and also intended to crown the image with a gold crown. Boturini began a fundraising effort to obtain the money to buy that gold crown. These very public activities of a foreigner raised suspicions from the colonial government in Mexico City. Boturini was arrested and accused of entering New Spain on official business without a special license from the Council of the Indies and for introducing papal documents without a royal permit. The Viceroy of New Spain, Pedro Cebrián y Agustin, the 5th Count of Fuenclara, imprisoned Boturini and impounded his collection. After spending 8 months in jail, Boturini was sent to Spain, but his collection – including the Mapa Tlotzin – remained in the office of the secretary of the viceroyalty in Mexico City. There, the collection was neglected and over time was subject to pilferage by bureaucrats. In Spain, Boturini was absolved of all wrongdoing by the Council of the Indies. The Spanish king was taken by the case and was impressed by the Italian nobleman’s knowledge and interest in this prized overseas possession. The king then made Boturini the official royal chronicler of the Indies and ordered that his collection be returned to him. The collection never was never restored to Boturini, including the famous painted map from Texcoco. With a new viceroy in Mexico City, the Boturini Collection was given to a historian named Mariano Fernández who, upon his death, passed it to Mexican anthropologist and astronomer Antonio de León y Gama. When he died in 1802 the Boturini Collection passed to his heirs who broke it up and sold off different pieces to various collectors. By 1889 the Mapa Tlotzin ended up in the hands of Eugene Goupil, a Mexican of French descent. When Goupil died in 1896, his widow donated the mapa and other ancient Mexican works to the National Library of France in Paris. There has been a movement to repatriate these documents and paintings to Mexico, but the French are loath to let go of such a valuable and historically important piece as the Mapa Tlotzin.

REFERENCES

SPITLER, Susan. “THE ‘MAPA TLOTZIN’ : PRECONQUEST HISTORY IN COLONIAL TEXCOCO.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes 84, no. 2 (1998): 71–81.