Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date is February 21, 1978. In Mexico City, workers for the state-run electric company, Comisión Federal de Electricidad, were digging in a residential area near the Metropolitan Cathedral known as “La Isla de los Perros,” or “The Island of the Dogs,” in English. The area was named because whenever Mexico City experienced torrential rains and flooding, street dogs would congregate in the area. A few meters down the electric company workers hit a massive disk-shaped stone slab measuring almost 11 feet in diameter and almost one foot thick. On the surface of this stone was carved the image of a decapitated and dismembered woman. As is customary in the Aztec artistic tradition for representations of deities, the woman has what archaeologists call “monster faces” on her joints. On her cheeks were carved representations of bells and from this, archaeologists knew exactly who she was. The goddess Coyolxauqui’s name in English translates to “Bells Her Cheeks.” Everything made sense because the image fit the story of the goddess Coyolxauqui as told by the Aztecs who the Spanish encountered as a living, breathing civilization.

The date is February 21, 1978. In Mexico City, workers for the state-run electric company, Comisión Federal de Electricidad, were digging in a residential area near the Metropolitan Cathedral known as “La Isla de los Perros,” or “The Island of the Dogs,” in English. The area was named because whenever Mexico City experienced torrential rains and flooding, street dogs would congregate in the area. A few meters down the electric company workers hit a massive disk-shaped stone slab measuring almost 11 feet in diameter and almost one foot thick. On the surface of this stone was carved the image of a decapitated and dismembered woman. As is customary in the Aztec artistic tradition for representations of deities, the woman has what archaeologists call “monster faces” on her joints. On her cheeks were carved representations of bells and from this, archaeologists knew exactly who she was. The goddess Coyolxauqui’s name in English translates to “Bells Her Cheeks.” Everything made sense because the image fit the story of the goddess Coyolxauqui as told by the Aztecs who the Spanish encountered as a living, breathing civilization.

According to Aztec myth one day Coyolxauqui’s mother, the goddess Coatlicue, or “Skirt of Snakes” in English, one of the main deities of ancient central Mexico, was sweeping on top of Snake Mountain. Out of the sky a ball of feathers fell into Coatlicue’s apron, and caused her to become pregnant. Coatlicue’s daughter, Coyolxauqui, the subject of the disk-like slab uncovered in Mexico City, became angry that someone would defile her mother and cause a pregnancy. She rallied her 400 brothers and stormed Snake Mountain to put her mother to death in a sort of honor killing. Immediately before the attack, Huitzilopotchli, the Aztec god of war and heavenly protector of the Aztec Empire, sprang from Coatlicue, fully armed, to defend his mother. Huitzilopotchtli defeated Coyolxauqui and her army and took her body, chopped it up and threw it down off Snake Mountain. The war god was not without compassion for his mother, though, knowing she would grieve for the loss of her daughter, Coyolxauqui. So, Huitzilopotchli took Coyolxauqui’s head and tossed it up to the sky where it became the moon, and Coatlicue would never be far from her daughter.

According to Aztec myth one day Coyolxauqui’s mother, the goddess Coatlicue, or “Skirt of Snakes” in English, one of the main deities of ancient central Mexico, was sweeping on top of Snake Mountain. Out of the sky a ball of feathers fell into Coatlicue’s apron, and caused her to become pregnant. Coatlicue’s daughter, Coyolxauqui, the subject of the disk-like slab uncovered in Mexico City, became angry that someone would defile her mother and cause a pregnancy. She rallied her 400 brothers and stormed Snake Mountain to put her mother to death in a sort of honor killing. Immediately before the attack, Huitzilopotchli, the Aztec god of war and heavenly protector of the Aztec Empire, sprang from Coatlicue, fully armed, to defend his mother. Huitzilopotchtli defeated Coyolxauqui and her army and took her body, chopped it up and threw it down off Snake Mountain. The war god was not without compassion for his mother, though, knowing she would grieve for the loss of her daughter, Coyolxauqui. So, Huitzilopotchli took Coyolxauqui’s head and tossed it up to the sky where it became the moon, and Coatlicue would never be far from her daughter.

As an aside, the discovery of the gigantic round stone of Coyolxuaqui found near the Metropolitan Cathedral in Mexico City in 1978 actually led to a more important discovery. Through further excavation around the discovery site, archaeologists realized that they had finally found the Templo Mayor, or main pyramid complex of the civic-ceremonial center of the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. The whereabouts of the templo’s location had been the topic of speculation of centuries, but with the 1978 discovery of the moon goddess’ stone, the location was confirmed. The stone, appropriately, was found at the base of the pyramid. The myth of Snake Mountain would be reenacted at the pyramid by the Aztecs during the festival of Panquetzalitztli, when dismembered bodies of sacrificial victims would be hurled down the stairs of the pyramid, eventually landing on Coyolxauqui’s stone. The moon goddess thus became the receiver of blood sacrifices and played an important role in the Aztec ritual calendar.

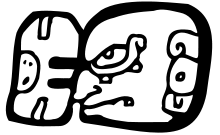

Very few sources exist of other moon deities in Ancient Mexico as the Aztecs were the major complex society in control of central Mexico at the time of the arrival of the Spanish and garnered the most scholarly attention from the Catholic clergy which sought to document and learn as much as they could from the Indians. The complex civilization of the Maya had collapsed about 6 centuries before the Spanish arrival and those Maya remaining in the heartland of the ancient civilization still had some of the old beliefs documented by the occasional conquistador, friar or priest. One of the first Europeans to explore the eastern Yucatán Peninsula, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, arrived ashore in March of 1517 with over 100 disgruntled settlers from Cuba. Hernández de Córdoba noted that on the island of Cozumel – known by the Maya as Kùutsmil – there was a shrine to the Maya moon goddess Ix-Chel. A priest would sit inside of a statue and give oracles to the women who would travel there to ask for blessings and advice regarding marriage and childbirth. Ix-Chel was usually represented as having a snake on her head and a skirt decorated in a crossbones pattern. Often times she was depicted as having claws for hands and feet. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba also noticed that the small island north of Cozumel served as some sort of secondary pilgrimage site for the moon goddess and he found it littered in small statues and figurines, and other representations of Ix-Chel. The name Hernández de Córdoba gave to that small island to this day still bears the name he gave it: Isla Mujeres, or in English, The Island of Women. In the local Maya dialect, Ix-Chel literally meant, “Lady Rainbow,” and in addition to being the moon goddess, she had other aspects and functions. In the book written by the Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English The List of Things in the Yucatán, the moon goddess Ix-Chel was associated with medicine, and according to de Landa in the month the Maya called Zip the Maya celebrated the feast of Ihcil Ix-Chel which honored physicians and shamans and included rituals involving divination stones and medicine bundles. De Landa also mentions that during what is called the “Ritual of the Bacabs,” the moon goddess is also referred to “grandmother.” In another Spanish source, the 16th Century historian and Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas relates a story of Ix-Chel and her husband Itzamna created the heaven and the earth, and together had 13 sons.

Very few sources exist of other moon deities in Ancient Mexico as the Aztecs were the major complex society in control of central Mexico at the time of the arrival of the Spanish and garnered the most scholarly attention from the Catholic clergy which sought to document and learn as much as they could from the Indians. The complex civilization of the Maya had collapsed about 6 centuries before the Spanish arrival and those Maya remaining in the heartland of the ancient civilization still had some of the old beliefs documented by the occasional conquistador, friar or priest. One of the first Europeans to explore the eastern Yucatán Peninsula, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, arrived ashore in March of 1517 with over 100 disgruntled settlers from Cuba. Hernández de Córdoba noted that on the island of Cozumel – known by the Maya as Kùutsmil – there was a shrine to the Maya moon goddess Ix-Chel. A priest would sit inside of a statue and give oracles to the women who would travel there to ask for blessings and advice regarding marriage and childbirth. Ix-Chel was usually represented as having a snake on her head and a skirt decorated in a crossbones pattern. Often times she was depicted as having claws for hands and feet. Francisco Hernández de Córdoba also noticed that the small island north of Cozumel served as some sort of secondary pilgrimage site for the moon goddess and he found it littered in small statues and figurines, and other representations of Ix-Chel. The name Hernández de Córdoba gave to that small island to this day still bears the name he gave it: Isla Mujeres, or in English, The Island of Women. In the local Maya dialect, Ix-Chel literally meant, “Lady Rainbow,” and in addition to being the moon goddess, she had other aspects and functions. In the book written by the Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa called Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, or in English The List of Things in the Yucatán, the moon goddess Ix-Chel was associated with medicine, and according to de Landa in the month the Maya called Zip the Maya celebrated the feast of Ihcil Ix-Chel which honored physicians and shamans and included rituals involving divination stones and medicine bundles. De Landa also mentions that during what is called the “Ritual of the Bacabs,” the moon goddess is also referred to “grandmother.” In another Spanish source, the 16th Century historian and Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas relates a story of Ix-Chel and her husband Itzamna created the heaven and the earth, and together had 13 sons.

As previously mentioned, the Spanish arrived to the Maya areas century after the civilization of the Classic Maya had collapsed. What we know of the moon goddess from the height of the complex ancient Maya civilization of interconnected and warring city-states comes from the remaining written and illustrated records interpreted by archaeologists and historians. These records may appear on monumental architecture or other public works, on pottery or other ceramics or in the few remaining Maya painted bark books called codices. In the Temple of the Warriors and the Temple of the Jaguars at Chichén Itzá the moon goddess is represented among many warriors, kings and captives as an old toothless matriarch. This is her Classic period form in illustrations. In writing she is often represented by a moon sign holding a rabbit. The goddess’ head functions as both the representation of the number one and the phonetic symbol pronounced “na.” In the ancient Maya world, na meant “noblewoman,” and so the head of the moon goddess usually preceded the written names of female elites. In some representations, the moon goddess is the drawing of an elaborately dressed woman sitting inside a crescent moon. In the Dresden Codex, an ancient Maya pictographic bark book, and known as the oldest book in the Americas, the moon goddess corresponds to what early Maya scholars first labeled “Goddess O.” In this codex the moon goddess is depicted as having a face of an old woman and the ears of a jaguar. This image is repeated in a few vases discovered at archaeological sites where the same “Goddess O” is shown as a physician, midwife and weaver. Some archaeologists and historians theorize that the ancient Maya moon goddess might have been much fiercer than previously thought and that her jaguar aspects – her ears and claws – combined with her gaping mouth, may suggest cannibalism. She is also thought to be connected to the maize god, the jaguar god of the underworld, the death god, and an aged god in the Dresden Codex known only as “God L.” The moon goddess of the ancient Maya has also been associated with several things connected with water,

As previously mentioned, the Spanish arrived to the Maya areas century after the civilization of the Classic Maya had collapsed. What we know of the moon goddess from the height of the complex ancient Maya civilization of interconnected and warring city-states comes from the remaining written and illustrated records interpreted by archaeologists and historians. These records may appear on monumental architecture or other public works, on pottery or other ceramics or in the few remaining Maya painted bark books called codices. In the Temple of the Warriors and the Temple of the Jaguars at Chichén Itzá the moon goddess is represented among many warriors, kings and captives as an old toothless matriarch. This is her Classic period form in illustrations. In writing she is often represented by a moon sign holding a rabbit. The goddess’ head functions as both the representation of the number one and the phonetic symbol pronounced “na.” In the ancient Maya world, na meant “noblewoman,” and so the head of the moon goddess usually preceded the written names of female elites. In some representations, the moon goddess is the drawing of an elaborately dressed woman sitting inside a crescent moon. In the Dresden Codex, an ancient Maya pictographic bark book, and known as the oldest book in the Americas, the moon goddess corresponds to what early Maya scholars first labeled “Goddess O.” In this codex the moon goddess is depicted as having a face of an old woman and the ears of a jaguar. This image is repeated in a few vases discovered at archaeological sites where the same “Goddess O” is shown as a physician, midwife and weaver. Some archaeologists and historians theorize that the ancient Maya moon goddess might have been much fiercer than previously thought and that her jaguar aspects – her ears and claws – combined with her gaping mouth, may suggest cannibalism. She is also thought to be connected to the maize god, the jaguar god of the underworld, the death god, and an aged god in the Dresden Codex known only as “God L.” The moon goddess of the ancient Maya has also been associated with several things connected with water,  including rainfall and wells. There are many aspects of the ancient lunar deity that are open to speculation or are just not known. She is often associated with a rabbit, for example, and it is unknown whether or not the rabbit is an animal companion of the goddess or may be symbolic of a “trickster” and serves to illustrate a characteristic of the goddess. Among the modern-day Maya of Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas, an elder brother of the sun who was also the son of the moon goddess was transformed into a rabbit after he allowed wild plants to grow in the sun’s cornfield. As punishment, in addition to being turned into a rabbit, the sun’s brother gave him to the moon goddess who threw him up into the sky where he attached himself to the moon. So, to some modern-day Maya instead of the “Man in the Moon,” there is a “Rabbit in the Moon,” put there by the moon goddess herself. As there were centuries “missing” between the Classic Maya writings and the conquest of the Maya lands by the Spanish, it is unclear how the moon goddess changed over time, or if the ancient goddess retained all of her same aspects or functions into the modern historical period. There are some elements of the Maya moon goddess, like the rabbit story that seem to have survived many centuries.

including rainfall and wells. There are many aspects of the ancient lunar deity that are open to speculation or are just not known. She is often associated with a rabbit, for example, and it is unknown whether or not the rabbit is an animal companion of the goddess or may be symbolic of a “trickster” and serves to illustrate a characteristic of the goddess. Among the modern-day Maya of Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas, an elder brother of the sun who was also the son of the moon goddess was transformed into a rabbit after he allowed wild plants to grow in the sun’s cornfield. As punishment, in addition to being turned into a rabbit, the sun’s brother gave him to the moon goddess who threw him up into the sky where he attached himself to the moon. So, to some modern-day Maya instead of the “Man in the Moon,” there is a “Rabbit in the Moon,” put there by the moon goddess herself. As there were centuries “missing” between the Classic Maya writings and the conquest of the Maya lands by the Spanish, it is unclear how the moon goddess changed over time, or if the ancient goddess retained all of her same aspects or functions into the modern historical period. There are some elements of the Maya moon goddess, like the rabbit story that seem to have survived many centuries.

Some scholars argue that in certain regions of the Maya world the moon may have been seen as something altogether different or may have had other functions and symbolism associated with it. The 16th Century Maya chronicle called the Popol Vuh, tells the story of the Hero Twins, a pair of demi-gods with supernatural powers who made frequent visits to the Underworld. In one version of the story, the twins recovered the bodies of their uncle and father and put them up in the sky as the sun and the moon. In another version of the story the twins climbed out of the Underworld to the surface of the earth and then climbed into the sky to become the sun and the moon themselves. This story seems to conflict with the idea of a traditional goddess of the moon. Scholars explain that the Twin story may be a metaphor or fable existing outside of religion much like the idea of the mythical Mother Nature existing as a separate legend apart from the creator Christian God in Western European culture.

What of other ancient Mexican cultures besides the Aztecs and Maya? Did they also have moon goddesses? Little is known about the religion of the Toltecs who ruled over central Mexico before the Aztecs. Scholars know that the Toltecs were polytheistic and they gave importance to the plumed serpent deity, but there is some speculation as to whether or not that this deity represented a real person. Very little evidence exists to show a moon goddess, but there is very little information at all on the gods of the Toltecs as their civilization ended by the 12th Century and they left behind no written record. The predecessors of the Toltecs in ancient Mexico were the Teotihuacanos, who were culturally dominant around the time of Christ and the Olmecs before them who were active from 1500 BC to 400 BC. Very little is known about the religious beliefs of these peoples other than they were polytheistic. Archaeologists and other scholars have identified and labeled certain gods of the Olmecs as their images recur in various artistic expressions. Researchers who subscribe to what has been termed “The Continuity Hypothesis” believe that all of the cultures in ancient Mexico took elements from the previous cultures of the same area who had power before them, and thus a great continuity exists across thousands of years throughout the region. Perhaps the moon goddess and her rabbit companion go back several thousand years, but with no concrete written record or imperfect archaeological records, it is almost impossible to tell.

What of other ancient Mexican cultures besides the Aztecs and Maya? Did they also have moon goddesses? Little is known about the religion of the Toltecs who ruled over central Mexico before the Aztecs. Scholars know that the Toltecs were polytheistic and they gave importance to the plumed serpent deity, but there is some speculation as to whether or not that this deity represented a real person. Very little evidence exists to show a moon goddess, but there is very little information at all on the gods of the Toltecs as their civilization ended by the 12th Century and they left behind no written record. The predecessors of the Toltecs in ancient Mexico were the Teotihuacanos, who were culturally dominant around the time of Christ and the Olmecs before them who were active from 1500 BC to 400 BC. Very little is known about the religious beliefs of these peoples other than they were polytheistic. Archaeologists and other scholars have identified and labeled certain gods of the Olmecs as their images recur in various artistic expressions. Researchers who subscribe to what has been termed “The Continuity Hypothesis” believe that all of the cultures in ancient Mexico took elements from the previous cultures of the same area who had power before them, and thus a great continuity exists across thousands of years throughout the region. Perhaps the moon goddess and her rabbit companion go back several thousand years, but with no concrete written record or imperfect archaeological records, it is almost impossible to tell.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

The Maya by Michael D. Coe

A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya by Linda Schele and David Freidel

The Popol Vuh

The Aztecs, the Maya and their Predecessors by Muriel Porter Weaver