Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the 2008 movie “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” the film’s namesake finds out that an old colleague of his named “Ox” Oxley discovered a crystal skull in Peru before he was abducted by the Soviets. Dr. Jones then travels to Peru and by using clues left by Oxley, he finds the crystal skull in the grave of Francisco de Orellana, the Spanish conquistador who explored the Amazon in the 1540s. Indiana Jones gets captured by the Russians and is taken to a camp in the jungle. While there, a villainous Soviet agent played by Cate Blanchett tells him that she believes the crystal skulls to be alien in origin and that they are from the mythical city of Akator. So, they all set out for Akator and after several mishaps and avoiding the usual pitfalls and dangers found in these movies, they arrive at this lost city. They soon reach a circular chamber where they see 13 crystal bodies of aliens with one missing a skull. The female Soviet agent places the crystal skull on the headless body and then all the skeletons combine into a real alien. An interdimensional portal appears, the legendary city of Akator gets destroyed and Indiana Jones survives to teach more classes at Marshall College and to appear in a final move 15 years later. And what does this have to do with ancient Mexico? Well, many elements of the Indiana Jones movie come from real life and from real world legends. On this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will explore the official narratives, the rumors and the counter-narratives associated with these mysterious ancient Aztec crystal skulls.

In the 2008 movie “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” the film’s namesake finds out that an old colleague of his named “Ox” Oxley discovered a crystal skull in Peru before he was abducted by the Soviets. Dr. Jones then travels to Peru and by using clues left by Oxley, he finds the crystal skull in the grave of Francisco de Orellana, the Spanish conquistador who explored the Amazon in the 1540s. Indiana Jones gets captured by the Russians and is taken to a camp in the jungle. While there, a villainous Soviet agent played by Cate Blanchett tells him that she believes the crystal skulls to be alien in origin and that they are from the mythical city of Akator. So, they all set out for Akator and after several mishaps and avoiding the usual pitfalls and dangers found in these movies, they arrive at this lost city. They soon reach a circular chamber where they see 13 crystal bodies of aliens with one missing a skull. The female Soviet agent places the crystal skull on the headless body and then all the skeletons combine into a real alien. An interdimensional portal appears, the legendary city of Akator gets destroyed and Indiana Jones survives to teach more classes at Marshall College and to appear in a final move 15 years later. And what does this have to do with ancient Mexico? Well, many elements of the Indiana Jones movie come from real life and from real world legends. On this episode of Mexico Unexplained, we will explore the official narratives, the rumors and the counter-narratives associated with these mysterious ancient Aztec crystal skulls.

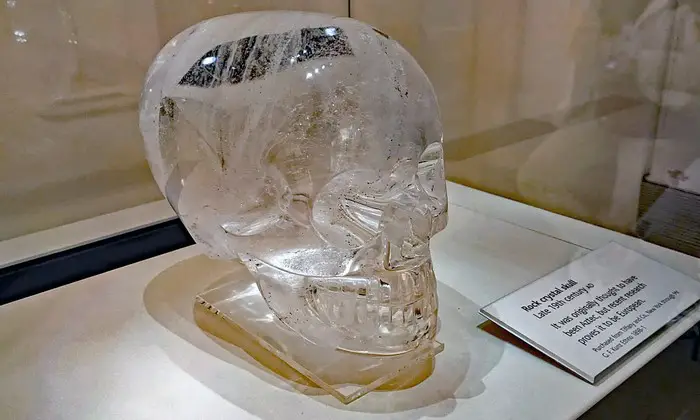

Crystal skulls have been finding themselves into private collections and museum exhibits since the late 1800s when interest in ancient Mexican artifacts began. Some scholars have been claiming that the majority of them – or even all of them – are expertly crafted fakes, but serious research into these strange, handcrafted pieces only began in the early 1990s. In 1992 a crystal skull the size of a football helmet was sent anonymously to the Smithsonian Institution along with a note explaining that it was Aztec and was originally part of the private collection of long-time Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz which was purchased in 1960. Smithsonian employees were intrigued by this random donation which would later carry a Smithsonian catalog designation A562841-0. As this curious piece arrived anonymously and with little more than a short note along with it, researchers at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History had to start from scratch with their investigation into this Aztec crystal skull. They first checked the Smithsonian’s collection to see if any similar artifacts existed in their vast inventory. They were surprised to find that the Institution already had a crystal skull artifact that came to it as part of a much larger collection of ancient Mexican art objects acquired in the late 1800s. This skull, measuring only 2 inches tall, was accompanied by a catalog card dating to the 1950s. On the card was an analysis done by an expert geologist named William Foshag who was an expert in ancient Mesoamerican carved stones. The catalog card declared “definitely a fake” and included a brief explanation on how the skull was fashioned by using modern – i.e., late 19th Century – tools and techniques. As already mentioned, the small crystal skull was part of a larger collection, and accompanying that collection was paperwork that went beyond mere catalog cards. In those documents Smithsonian researchers found a letter dating to the year 1886 describing how a man named Eugène Boban once tried to sell a fake Aztec crystal skull to the National Museum in Mexico. Those researching the skulls then decided to pursue Boban as a possible lead to unravel the mystery of all the supposed ancient Mexican crystal skulls found scattered throughout the world. Who was Eugène Boban and what exactly was his connection to this mystery?

Crystal skulls have been finding themselves into private collections and museum exhibits since the late 1800s when interest in ancient Mexican artifacts began. Some scholars have been claiming that the majority of them – or even all of them – are expertly crafted fakes, but serious research into these strange, handcrafted pieces only began in the early 1990s. In 1992 a crystal skull the size of a football helmet was sent anonymously to the Smithsonian Institution along with a note explaining that it was Aztec and was originally part of the private collection of long-time Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz which was purchased in 1960. Smithsonian employees were intrigued by this random donation which would later carry a Smithsonian catalog designation A562841-0. As this curious piece arrived anonymously and with little more than a short note along with it, researchers at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History had to start from scratch with their investigation into this Aztec crystal skull. They first checked the Smithsonian’s collection to see if any similar artifacts existed in their vast inventory. They were surprised to find that the Institution already had a crystal skull artifact that came to it as part of a much larger collection of ancient Mexican art objects acquired in the late 1800s. This skull, measuring only 2 inches tall, was accompanied by a catalog card dating to the 1950s. On the card was an analysis done by an expert geologist named William Foshag who was an expert in ancient Mesoamerican carved stones. The catalog card declared “definitely a fake” and included a brief explanation on how the skull was fashioned by using modern – i.e., late 19th Century – tools and techniques. As already mentioned, the small crystal skull was part of a larger collection, and accompanying that collection was paperwork that went beyond mere catalog cards. In those documents Smithsonian researchers found a letter dating to the year 1886 describing how a man named Eugène Boban once tried to sell a fake Aztec crystal skull to the National Museum in Mexico. Those researching the skulls then decided to pursue Boban as a possible lead to unravel the mystery of all the supposed ancient Mexican crystal skulls found scattered throughout the world. Who was Eugène Boban and what exactly was his connection to this mystery?

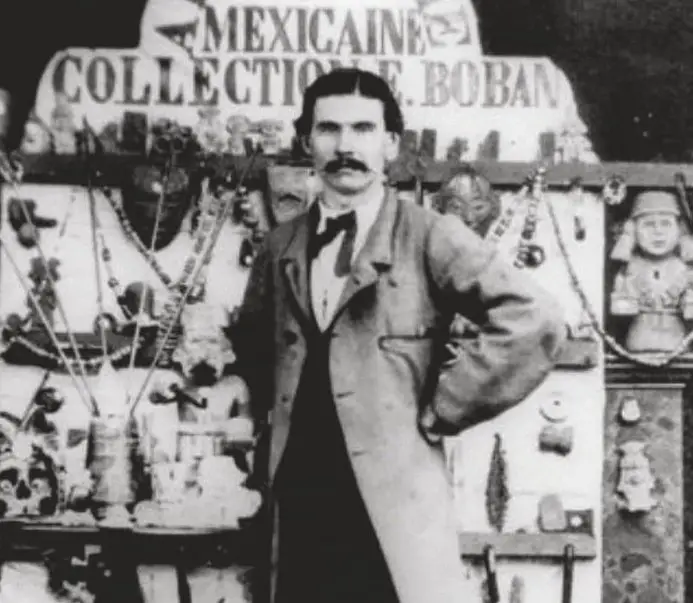

Eugène Boban was born in France in 1834. From a young age he was interested in the newly emerging science of archaeology and in studying relics of ancient civilizations. In 1857, at the age of 23, he was sent to Mexico by the French Emperor Napoleon III to collect Mexican art and artifacts to later be displayed at the International Exposition in Paris in 1867. Boban learned Spanish and Nahuatl and traveled throughout Mexico gathering material on behalf of the French emperor. When the politics changed in Mexico and the conservative elites of the country invited a European monarch to rule over them, Eugène Boban became the official court archaeologist of the newly installed Mexican Emperor Maximilian. At the same time Boban was a member of the French Scientific Commission in Mexico. This man had many connections in antiquarian circles in both Mexico and Europe and was very familiar with Mexico’s many archaeological sites and private artifact collections. Boban’s expertise on all things ancient Mexico earned him a solid reputation among museum curators and serious collectors of Mesoamerican artifacts. Critics of Boban claimed that he used this blind faith others had in him to traffic in fakes, as there were very few people in the United States or Europe in the late 1800s – from serious antiquarians to seasoned museum curators – who had experience with the artifacts of the ancient cultures coming out of Mexico. In 1870 Eugène Boban opened a shop in Paris specializing in ancient objects and 16 years later moved his business to New York City. From his two business locations, he sold a handful of Aztec crystal skulls to collectors and museums. Many of the crystal skulls known to exist can be traced directly to Eugène Boban.

Eugène Boban was born in France in 1834. From a young age he was interested in the newly emerging science of archaeology and in studying relics of ancient civilizations. In 1857, at the age of 23, he was sent to Mexico by the French Emperor Napoleon III to collect Mexican art and artifacts to later be displayed at the International Exposition in Paris in 1867. Boban learned Spanish and Nahuatl and traveled throughout Mexico gathering material on behalf of the French emperor. When the politics changed in Mexico and the conservative elites of the country invited a European monarch to rule over them, Eugène Boban became the official court archaeologist of the newly installed Mexican Emperor Maximilian. At the same time Boban was a member of the French Scientific Commission in Mexico. This man had many connections in antiquarian circles in both Mexico and Europe and was very familiar with Mexico’s many archaeological sites and private artifact collections. Boban’s expertise on all things ancient Mexico earned him a solid reputation among museum curators and serious collectors of Mesoamerican artifacts. Critics of Boban claimed that he used this blind faith others had in him to traffic in fakes, as there were very few people in the United States or Europe in the late 1800s – from serious antiquarians to seasoned museum curators – who had experience with the artifacts of the ancient cultures coming out of Mexico. In 1870 Eugène Boban opened a shop in Paris specializing in ancient objects and 16 years later moved his business to New York City. From his two business locations, he sold a handful of Aztec crystal skulls to collectors and museums. Many of the crystal skulls known to exist can be traced directly to Eugène Boban.

Just like in the Indiana Jones movie, there are supposedly 13 crystal skulls that exist that were manufactured somewhere in ancient Mesoamerica. According to modern-day New Age lore, when the skulls are in one place, a cosmic shift will occur, or an interdimensional portal will open. Does this modern-day take have any basis in the belief systems of ancient Mexican cultures? The answer to this is “no,” or at least any beliefs that may have existed are not yet known. When they encountered the Aztecs as a living, breathing civilization, the Spanish noted that the human skull played important roles in Aztec religion and in their art and iconography. There is no mention in any Spanish chronicle of skulls made of crystal, and there is no pre-hispanic codex or other form of documentation that mentions crystal skulls. It seems that the whole idea of 13 skulls coming together is a relatively new belief and is not based on anything historic. Besides the football-helmet-sized skull mailed to the Smithsonian in 1992 and its little brother that was already in the Smithsonian’s collection for almost 100 years, there are 3 other famous ancient Mesoamerican crystal skulls that have been examined and studied thoroughly.

The first of these is the crystal skull in the British Museum. This one has a traceable provenance to a point. The museum acquired it in 1897, and documentation states that it was bought from Tiffany and Company which had purchased it at auction. The previous owner was George H. Sisson, an American businessman who started the Mexican Land and Colonization Company along with British backers. For more information about this man and his company please see Mexico Unexplained Episode #282 https://youtu.be/gYZpFstNVoE With many interests and financial stakes in Mexico, Sisson was taken by Mexico’s ancient past and owned a collection of ancient artifacts from that country. Ironically, Sisson did not buy that skull that currently sits in the British Museum directly from a Mexican in Mexico, he purchased it from none other than Eugène Boban. An article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in 2008 explained results of tests taken on the British Museum crystal skull. Researchers believe that the skull was fashioned from quartz crystal originally sourced from Brazil and by using electron microscopy and x-ray crystallography, they were able to determine that the makers of the skull used a harsh abrasive such as diamond or corundum to polish it, while the skull itself was shaped by metal rotary tools common in jewelry making in the late 1800s. Further research suggested that Boban contracted out the making of the skulls to a workshop in Germany.

The first of these is the crystal skull in the British Museum. This one has a traceable provenance to a point. The museum acquired it in 1897, and documentation states that it was bought from Tiffany and Company which had purchased it at auction. The previous owner was George H. Sisson, an American businessman who started the Mexican Land and Colonization Company along with British backers. For more information about this man and his company please see Mexico Unexplained Episode #282 https://youtu.be/gYZpFstNVoE With many interests and financial stakes in Mexico, Sisson was taken by Mexico’s ancient past and owned a collection of ancient artifacts from that country. Ironically, Sisson did not buy that skull that currently sits in the British Museum directly from a Mexican in Mexico, he purchased it from none other than Eugène Boban. An article published in the Journal of Archaeological Science in 2008 explained results of tests taken on the British Museum crystal skull. Researchers believe that the skull was fashioned from quartz crystal originally sourced from Brazil and by using electron microscopy and x-ray crystallography, they were able to determine that the makers of the skull used a harsh abrasive such as diamond or corundum to polish it, while the skull itself was shaped by metal rotary tools common in jewelry making in the late 1800s. Further research suggested that Boban contracted out the making of the skulls to a workshop in Germany.

In that same Journal of Archaeological Science article just mentioned, the authors presented research on the huge skull mailed to the Smithsonian in 1992. It, too, was worked with metal tools but with a different, more recently invented abrasive: silicon carbide. Although this abrasive was around in the 1890s, its widespread use only came about a few decades into the 20th Century. Researchers concluded that the skull was probably made after 1950 and had no connection to the French antiquarian Eugène Boban. At the Smithsonian this Aztec crystal skull is on display and the National Museum of Natural History boldly asserts that the skull is a modern fake.

Another famous ancient Mexican crystal skull is known as the Paris Skull and is being held in a collection of the Quai Branley Museum in Paris, an institution specializing in indigenous art from outside of Europe. This skull has a Eugène Boban connection. The French antiquities dealer sold this skull, and two others, to French collector Alphonse Pinart. In 2007 The Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums in France tested this skull using quartz hydration dating and scanning electron microscopy. Their conclusion was that the Paris Skull was either made in the late 1700s or sometime in the 1800s.

Perhaps the most famous of the ancient Mexican crystal skulls is known as the Mitchell-Hedges Skull and is attributed to the Maya civilization, not the Aztec. It was supposedly found in 1924 by a little girl in the Mayan ruins of Lubantuum in what was then called British Honduras, now Belize. The little girl was Anna Mitchell-Hedges, the daughter of English adventurer and travel writer Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges. This skull had been the subject of much interest and the topic of many documentaries, books, and magazine articles. The family rarely showed the skull to the public and refused to subject it to scientific testing or other scholarly examinations of any kind. It was only when Anna Mitchell-Hedges died in 2007 that the skull was tested for the first time. What researchers found was consistent with the others: the supposed ancient artifact was fashioned using modern methods and tools. Additionally, it was later discovered that Mitchell-Hedges bought the skull at Sotheby’s in 1943 for 400 pounds and the whole story of the little girl finding the skull among the ruins of a Mayan lost city was all a lie.

Perhaps the most famous of the ancient Mexican crystal skulls is known as the Mitchell-Hedges Skull and is attributed to the Maya civilization, not the Aztec. It was supposedly found in 1924 by a little girl in the Mayan ruins of Lubantuum in what was then called British Honduras, now Belize. The little girl was Anna Mitchell-Hedges, the daughter of English adventurer and travel writer Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges. This skull had been the subject of much interest and the topic of many documentaries, books, and magazine articles. The family rarely showed the skull to the public and refused to subject it to scientific testing or other scholarly examinations of any kind. It was only when Anna Mitchell-Hedges died in 2007 that the skull was tested for the first time. What researchers found was consistent with the others: the supposed ancient artifact was fashioned using modern methods and tools. Additionally, it was later discovered that Mitchell-Hedges bought the skull at Sotheby’s in 1943 for 400 pounds and the whole story of the little girl finding the skull among the ruins of a Mayan lost city was all a lie.

While most mainstream scientists and researchers have dismissed all the crystal skulls as fakes and hoaxes, there are counter arguments challenging the scientific folks. Some claim that the skulls are not fakes but were “touched up” with modern tools which were used to polish them as part of the restoration process. Others claim that the ancients themselves possessed the sophisticated techniques to make the skulls, but this technology has been lost. There are still others who speculate that the skulls only ended up in ancient Mexico after the destruction of Atlantis and that artists on the lost continent are the real makers of these mysterious crystal creations. With more skulls yet to be discovered and/or tested, the scientific community might be in for a surprise if just one of them proves not to be a fake. Until that time, we can only wonder.

REFERENCES

Morton, Chris and Ceri Louise Thomas. The Mystery of the Crystal Skulls: Unlocking the Secrets of the Past, Present and Future. Rochester, VT: Bear and Co., 2002. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3OGWKrG

Walsh, Jane MacLaren. “Legend of the Crystal Skulls.” In Archaeology, 61 (3), 36-41, May/June 2008.