Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

She is known by many names, La Malinche, Doña Marina, Malinalli, Malintzin and disparagingly as La Chingada. Although many of the details of her life have been lost or embellished over time, history casts her alternatively in the role of savior, villain, lover, betrayer, evangelist, helper, and the mother of a new race. So, who exactly was Doña Marina and what role did she play in the history of Mexico?

She is known by many names, La Malinche, Doña Marina, Malinalli, Malintzin and disparagingly as La Chingada. Although many of the details of her life have been lost or embellished over time, history casts her alternatively in the role of savior, villain, lover, betrayer, evangelist, helper, and the mother of a new race. So, who exactly was Doña Marina and what role did she play in the history of Mexico?

The woman later known by her Spanish name Doña Marina was born sometime at the end of the 15th Century or the beginning of the 16th Century. Her given name was Malinalli, and she was named for the 12th day of the ancient Mesoamerican calendar. According to firsthand accounts published by Bernal Diaz, one of the Spanish conquistadors who arrived with Cortez and who knew Marina, she was from a minor noble family in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in south-central Mexico. Marina was most likely not a native speaker of Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire, but knew it fluently because it was the lingua franca of the region and known by many non-Aztec groups who were either subjugated by the Aztec Empire or who interacted with the Aztecs through trade. Most of what we know about Marina’s early life comes from Diaz’s written accounts, recorded almost 40 years after the Conquest in a book titled La historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva España. In English, this translates to “The true history of the conquest of New Spain.” When Marina was a young girl her father, who was the Cacique of Paynala, died and her mother remarried. With her new husband Marina’s mother  had a son. The mother wanted her son to inherit the family’s status and wealth and had a plan to send Marina away. When she was in her early teens, Marina’s mother sold her to traders in the market city of Xicalango and told everyone that Marina had died. In Xicalango Marina was sold off to a Maya lord who ruled Potonchán, a small kingdom located in the present Mexican state of Tabasco. When Marina was brought to Potonchán she served in the household of the noble lord, and after a short time she became fluent in the local Chontal Maya language. Up until that point, Marina was fluent in at least 3 languages: the native language of her town of birth, the Aztec language Nahuatl, and Chontal Maya.

had a son. The mother wanted her son to inherit the family’s status and wealth and had a plan to send Marina away. When she was in her early teens, Marina’s mother sold her to traders in the market city of Xicalango and told everyone that Marina had died. In Xicalango Marina was sold off to a Maya lord who ruled Potonchán, a small kingdom located in the present Mexican state of Tabasco. When Marina was brought to Potonchán she served in the household of the noble lord, and after a short time she became fluent in the local Chontal Maya language. Up until that point, Marina was fluent in at least 3 languages: the native language of her town of birth, the Aztec language Nahuatl, and Chontal Maya.

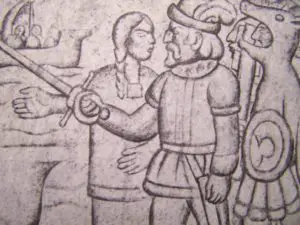

While Marina served in the house of the Chontal Maya ruler, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés was taking part in the conquest of the island of Cuba. While Cortés served the Spanish king in Cuba he heard stories of a mythical land to the west and about a mighty empire whose capital stood on an island in the middle of a lake. Cortés was determined to locate this city and take over the empire and in 1518 he left Cuba with over 500 ambitious Spaniards to undertake this grand scheme. His expedition landed on Mexico’s gulf coast and the Spaniards made contact with the local Maya-speaking people. In the course of the expedition’s journey down the coast, to their surprise Cortés and his men encountered a 30-year-old Spanish priest named Jeronimo de Aguilar who had been shipwrecked on the Mexican coast in 1511 and had lived among the Maya ever since. As a consequence of living among the coastal Maya for almost 7 years, Aguilar knew their language and proved invaluable to Cortés because he could translate for the expedition, at least in that region. Cortés used Aguilar to help form alliances and make deals with the locals. It was soon after meeting up with Aguilar that Doña Marina came back into the picture. In March of 1518, the Spanish arrived in the Maya kingdom of Potonchan where Marina served in the royal court. The Maya decided to fight the Spanish and lost. As part of their reparations the Maya gave the Spanish food, turquoise, jade objects and 20 young women, and Marina was among the group. The women were baptized by the two priests on the expedition and this is when Malinalli became Doña Marina. Marina was then given to one of Cortés’ friends Alonso Hernández Portocarrero.

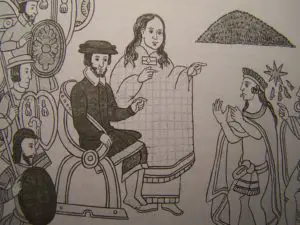

Marina showed her worth once the Spanish left the territories of the Maya-speaking people. Emperor Montezuma the Second, having heard of the arrival of the strangers from the east, sent emissaries to try to reason with Cortés and to at least find out his intentions. The emissaries met up with the Spanish Expedition on the fringes of the Aztec empire in a town where Cortés set up an encampment. The emissaries only spoke Nahuatl, a native language that Father Aguilar was unfamiliar with. Cortés was discouraged because Aguilar was of no use and there was no way for them to communicate. During the initial meeting with the Aztecs and amid the frustration, according to the firsthand accounts of Bernal Diaz, this is when Marina stepped in, and answered the questions of the emissaries and pointed to Cortés. Cortés was surprised that Marina knew Nahuatl and he devised a way to communicate with the Aztecs: Cortés would communicate in Spanish to Father Aguilar, Father Aguilar would speak to Marina in Chontal Maya, and Marina would speak to the Aztecs in their native language of Nahuatl. When the Aztecs would speak, the process would be reversed. This way, Cortés, through Marina, was able to communicate with many native groups on his march toward the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. Along the way they gathered intelligence from these groups and were thus better prepared to face Montezuma and the weight of his empire.

Marina showed her worth once the Spanish left the territories of the Maya-speaking people. Emperor Montezuma the Second, having heard of the arrival of the strangers from the east, sent emissaries to try to reason with Cortés and to at least find out his intentions. The emissaries met up with the Spanish Expedition on the fringes of the Aztec empire in a town where Cortés set up an encampment. The emissaries only spoke Nahuatl, a native language that Father Aguilar was unfamiliar with. Cortés was discouraged because Aguilar was of no use and there was no way for them to communicate. During the initial meeting with the Aztecs and amid the frustration, according to the firsthand accounts of Bernal Diaz, this is when Marina stepped in, and answered the questions of the emissaries and pointed to Cortés. Cortés was surprised that Marina knew Nahuatl and he devised a way to communicate with the Aztecs: Cortés would communicate in Spanish to Father Aguilar, Father Aguilar would speak to Marina in Chontal Maya, and Marina would speak to the Aztecs in their native language of Nahuatl. When the Aztecs would speak, the process would be reversed. This way, Cortés, through Marina, was able to communicate with many native groups on his march toward the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. Along the way they gathered intelligence from these groups and were thus better prepared to face Montezuma and the weight of his empire.

In the fall of 1519 the Spanish arrived at the independent Kingdom of Tlaxcala, just east of the Aztec homeland. The Tlaxcalans had fiercely resisted Aztec incursions into their territories and were some of the few independent kingdoms in central Mexico that held out against the armies of Montezuma. They greeted the Spanish with suspicion but through Marina, Cortés made a deal with the Tlaxcalan king not only to spare his men but to join him on his march to the Aztec capital. To the Tlaxcalans, Cortés represented an opportunity to crush their enemies once and for all and to rid Mesoamerica of the Aztec hegemony. When the expedition left the Tlaxcalan kingdom they had thousands of more soldiers in their ranks. This was a turning point in the Conquest of Mexico. It is unclear what would have happened in this situation without the help of Marina, who, after being with the expedition for over a year and a half, had mastered Spanish and could translate directly the wishes of Cortés.

While in Tlaxcala, Marina acquired one of her other names, “Malintzin”, which may translate loosely to “noble captive,” a reference to Marina’s noble birth and the fact that she was given to the Spanish as tribute in a war. The Spanish on the expedition could not pronounce the Nahuatl Malintzin and called Marina “Malinche”, sometimes using the definite article in Spanish “la” in front of her name. This is why Doña Marina is often referred to as “La Malinche” or in English texts, “The Malinche.”

From Tlaxcala, the Spanish expedition moved to Cholula. Here again Marina’s role was pivotal. Cholula was part of the Aztec Empire and didn’t trust the Tlaxcalans Cortés was traveling with. Cortés told the Cholulans, however, that he was traveling to Tenochtitlan on an official state visit to see Emperor Montezuma and needed quarter in the town as a favor to their overlord. The Cholulans reluctantly agreed. While there, Marina made friends with local women and soon found out about a plot that the Cholulan army was planning to attack the Spanish unsuspectedly. Marina told Cortés and the Spanish quickly attacked the Cholulans, killing thousands and disabling their army. Their path to the Aztec capital was now clear.

From Tlaxcala, the Spanish expedition moved to Cholula. Here again Marina’s role was pivotal. Cholula was part of the Aztec Empire and didn’t trust the Tlaxcalans Cortés was traveling with. Cortés told the Cholulans, however, that he was traveling to Tenochtitlan on an official state visit to see Emperor Montezuma and needed quarter in the town as a favor to their overlord. The Cholulans reluctantly agreed. While there, Marina made friends with local women and soon found out about a plot that the Cholulan army was planning to attack the Spanish unsuspectedly. Marina told Cortés and the Spanish quickly attacked the Cholulans, killing thousands and disabling their army. Their path to the Aztec capital was now clear.

The initial arrival at the Aztec capital was peaceful. On November 8, 1519 Cortés, followed by thousands, marched on the causeway across Lake Texcoco connecting Tenochtitlan to the mainland. In the middle of the causeway, Cortés was met by Montezuma and his entourage. Gifts were exchanged and to were pleasantries, with Marina as the go-between. The emperor invited the Spanish to enter the city, the Tlaxcalan warriors and all other non-Spaniards – with the exception of Marina – were told to stay on the mainland. Marina would serve a vital role in the ensuing two weeks, during which time the Spanish were received as honored guests.

It’s important to note how Marina completely broke the standards of behavior of Mesoamerican women at the time. Women in the Aztec Empire were prohibited from speaking in public places, especially at public events. Anyone surrounding the Aztec Emperor was required to look away from him. Marina, however, boldly spoke directly to Montezuma on Cortés’ behalf and always conducted herself in a noble way, according to Spanish and native observers. All would agree that she had a powerful, commanding presence which served to enhance her physical beauty. At one point, now a devout Christian, Marina even spoke fearlessly to Montezuma about converting to Christianity, telling him that the gods he worshipped were evil. This was definitely a bold woman.

The weeks of talks and deal-making did not yield what Cortés wanted and he had Montezuma taken prisoner. It was Marina who informed the emperor that he was to be taken captive. For six months Montezuma was in custody, a prisoner in his own land. Many people who were dissatisfied with Montezuma’s rule were indifferent to his imprisonment. During that time, however, the relations between the Spanish and the Aztecs slowly deteriorated. When Cortés was away from the city and when he Aztecs were having a nighttime celebration to honor one of their main gods, Huitzilipochtli, Cortés lieutenant, Pedro de Alvarado, attacked the celebrants, mistaking the fiesta for the beginnings of an armed insurrection against Spanish rule. Hundreds of unarmed nobles were killed and soon after, when Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan, the Aztecs were furious and began their open rebellion against the Spaniards. Some accounts say that Montezuma was hauled out of captivity and stoned to death by his own people, other accounts say that Cortés had Montezuma killed.

Right after Montezuma’s death, on the night of June 30, 1520, the Spanish retreated and fled Tenochtitlan. Hundreds of Spaniards and possibly over a thousand Tlaxcalans were killed as a full force of Aztecs attacked the invaders on the causeway and on the mainland. The night in history is known in Spanish as “La noche triste,” “the sad night.” Marina survived the battles by hiding under a bridge. She regrouped with Cortés and his forces. Nearly a year later, and with more help from surrounding tribes, the Spanish re-entered Tenochtitlan and completely subdued the Aztec capital. Marina was there at the side of Cortés to translate for the formal surrender on August 13, 1521.

Right after Montezuma’s death, on the night of June 30, 1520, the Spanish retreated and fled Tenochtitlan. Hundreds of Spaniards and possibly over a thousand Tlaxcalans were killed as a full force of Aztecs attacked the invaders on the causeway and on the mainland. The night in history is known in Spanish as “La noche triste,” “the sad night.” Marina survived the battles by hiding under a bridge. She regrouped with Cortés and his forces. Nearly a year later, and with more help from surrounding tribes, the Spanish re-entered Tenochtitlan and completely subdued the Aztec capital. Marina was there at the side of Cortés to translate for the formal surrender on August 13, 1521.

During the whole time of the expedition, Marina became closer to Cortés. Remember, Marina was “given” to the man named Portocarrero, but Cortés had sent him back to Spain half way through the expedition. After Portocarrero’s departure, Cortés took Marina as his mistress and they remained together for 4 years. After the fall of Tenochtitlan and after the new city of Mexico was built on its ruins, Marina lived with Cortés and gave birth to his first son, Martín, in May of 1522. Martín Cortés was the first publicly acknowledged person of mestizo, or mixed-race, heritage in Mexican history. This is the reason why Marina is sometimes referred to as “The Mother of Mexico.”

Marina took one last journey with Cortés to the Maya area of Honduras in 1524. Because Cortés had a legal wife in Cuba, Marina was free to marry, and on this 1524 trip she married a man named Juan Xaramillo de Salvatierra. On the journey to Honduras the expedition stopped at Marina’s birth town where she was able to visit family members. Instead of staying in this town she opted to continue the journey with the Spaniards to Central America. While there are no records of the rest of the life of Marina, there is a lot of speculation as to what happened to her. It is certain that after the Honduras expedition she never saw Cortés again because he returned to Spain soon after. There are various legends about the rest of her life, including that she died tragically of strangulation or that she died a very old woman. In any event, there are no records of her existence after the Honduras trip, save a brief mentioning of her still being alive in a text dated 1550 recently found in Spain.

Marina’s legacy lives on, mixing historical fact with myth, and full of pointed opinions as to her impact. Many people see her as a Judas figure, a traitor to the native peoples of Mesoamerica. There even exists a word in Spanish, malinchista, used to describe a disloyal or unfaithful person. Marina’s arrival in Tenochtitlan symbolizes the end of great indigenous civilizations of the Americas and she should never be forgiven for her betrayal. On the other hand, some see her as a liberator of the peoples who were living under the Aztec jackboot. With the Spanish arrival came the end of human sacrifice and the brutality of everyday life under the Aztecs. As a devout convert to Christianity, Marina is seen as an evangelist bringing a peaceful religion to a new people. Her closeness to Cortés is seen as a softening influence on the conquistador and many believe that with this influence the Conquest of Mexico was less brutal. As the mother of one of the first mixed-race children in the Americas Marina is seen as the mother of a new race, La Raza Cosmica, or the mestizo. Other modern interpretations see her as a scapegoat used to take the fall for whatever opinion one may have about the Conquest. It is generally agreed, though, that The Malinche was a woman caught in the middle, a person who used her intelligence and tact to the best of her ability when faced with difficult choices. We cannot know how she felt, as she left no written diary and no firsthand accounts of her exist outside of those brief passages written by Bernal Diaz. We can only guess what she was feeling as she saw the history of the New World unfold in front of her, a history that she played more than an active role in actually creating.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography):

The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico by Bernal Díaz del Castillo

Doña Marina, La Malinche by Ricardo Henren (in Spanish

Early Civilizations in the Americas: Biographies and Primary Sources by Sonia Benson

Conquest by Hugh Thomas

2 thoughts on “The Mysterious Doña Marina, the Most Important Woman in Mexican History”

The last paragraph of this article states that we cannot know how she felt. Actually, Bernal Diaz knew her well and gave us a pretty good idea of how she felt, when he related the encounter she had with her mother a couple of years after the conquest of the Aztecs. He states:

\”When Cortes was in the town of Coatzacoalcos he sent to summon to his presence all the Caciques of that province in order to make them a speech about our holy religion, and about their good treatment, and among the Caciques who assembled was the mother of Dona Marina and her half-brother, Lázaro.

Some time before this Dona Marina had told me that she belonged to that province and that she was the mistress of vassals, and Cortes also knew it well, as did Aguilar, the interpreter. In such a manner it was that mother, daughter and son came together, and it was easy enough to see that she was the daughter from the strong likeness she bore to her mother.

These relations were in great fear of Dona Marina, for they thought that she had sent for them to put them to death, and they were weeping.

When Dona Marina saw them in tears, she consoled them and told them to have no fear, that when they had given her over to the men from Xicalango, they knew not what they were doing, and she forgave them for doing it, and she gave them many jewels of gold, and raiment, and told them to return to their town, and said that God had been very gracious to her in freeing her from the worship of idols and making her a Christian, and letting her bear a son to her lord and master Cortes and in marrying her to such a gentleman as Juan Jaramillo, who was now her husband. That she would rather serve her husband and Cortes than anything else in the world, and would not exchange her place to be Cacica of all the provinces in New Spain.\”

Thanks for this!