Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1751. In a far-flung desert corner of New Spain, a Jesuit by the name of Ferdinand Konščak stared up at a massive wall painted with large human figures and animals. The young Jesuit was far from home. Born in a small town in the Kingdom of Croatia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Konščak was educated in a variety of places and was well-versed in many subjects. The bright young Father Ferdinand was assigned to Baja California in 1732. Adept at learning languages, he quickly picked up the various dialects of the Cochimí people, the original inhabitants of the area. Another one of the Croatian father’s interests was cartography. Konščak’s knowledge of local languages and his interest in mapping made him the perfect person to lead the expedition to explore and chart the interior of Baja California, which was so remote and ignored by the outside world that it was still considered an island at the start of Konščak’s explorations. While crossing the peninsula overland the natives took him to a series of caves in the Sierra de San Francisco located almost in the geographical center of Baja. Konščak noted in his diaries his own amazement at the quantity and size of the figures on the walls of the various overhangs, shallow caves and rock shelters he explored. Over the course of a few weeks he had seen thousands of paintings, some that were 10-12 feet off the surface of the ground. When he asked his Cochimí guides who painted these fabulous murals and how they were able to be painted at such heights, they simply told him that he was staring at the work of giants. The idea of a lost race of giants also appears in a 1789 work by Francisco Javier Clavigero titled Historia de la Antigua o Baja California, or in English, History of Old or Lower California. The author has a section on the ancient rock art and states that the pictures on the walls are of

The year was 1751. In a far-flung desert corner of New Spain, a Jesuit by the name of Ferdinand Konščak stared up at a massive wall painted with large human figures and animals. The young Jesuit was far from home. Born in a small town in the Kingdom of Croatia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Konščak was educated in a variety of places and was well-versed in many subjects. The bright young Father Ferdinand was assigned to Baja California in 1732. Adept at learning languages, he quickly picked up the various dialects of the Cochimí people, the original inhabitants of the area. Another one of the Croatian father’s interests was cartography. Konščak’s knowledge of local languages and his interest in mapping made him the perfect person to lead the expedition to explore and chart the interior of Baja California, which was so remote and ignored by the outside world that it was still considered an island at the start of Konščak’s explorations. While crossing the peninsula overland the natives took him to a series of caves in the Sierra de San Francisco located almost in the geographical center of Baja. Konščak noted in his diaries his own amazement at the quantity and size of the figures on the walls of the various overhangs, shallow caves and rock shelters he explored. Over the course of a few weeks he had seen thousands of paintings, some that were 10-12 feet off the surface of the ground. When he asked his Cochimí guides who painted these fabulous murals and how they were able to be painted at such heights, they simply told him that he was staring at the work of giants. The idea of a lost race of giants also appears in a 1789 work by Francisco Javier Clavigero titled Historia de la Antigua o Baja California, or in English, History of Old or Lower California. The author has a section on the ancient rock art and states that the pictures on the walls are of

“men and women, and the different species of animals. These paintings, although crude, show the objects distinctly. The colors that served for them are clearly seen to have been made from the mineral earths which are found in the region of the volcano of Las Virgenes. The missionaries most admired the fact that those colors should have remained permanent in the stone through many centuries without being damaged by either air or water. Not feeling those pictures and dress to belong to the savage and brutalized nations which inhabited California when the Spanish arrived there, they doubtless belong to another ancient nation, although we cannot say which it was. The Californians unanimously affirm that it was a nation of giants who came from the north.

“men and women, and the different species of animals. These paintings, although crude, show the objects distinctly. The colors that served for them are clearly seen to have been made from the mineral earths which are found in the region of the volcano of Las Virgenes. The missionaries most admired the fact that those colors should have remained permanent in the stone through many centuries without being damaged by either air or water. Not feeling those pictures and dress to belong to the savage and brutalized nations which inhabited California when the Spanish arrived there, they doubtless belong to another ancient nation, although we cannot say which it was. The Californians unanimously affirm that it was a nation of giants who came from the north.

Although the California Indians have been asked the meanings of the paintings, rays, and characters they could not offer any satisfactory explanation. The most that has been found out is that [the paintings] are of their ancestors and that those of today are completely ignorant of the meaning.”

What is now a geographical region consisting of a peninsula which is home to two Mexican States – Baja California and Baja California Sur – has always been a backwater. Indeed, Baja California Sur, a seemingly perpetual territory of Mexico only became a state in October of 1974, the last state to be admitted to the Mexican union. Outsiders avoided Baja for most of the peninsula’s history. For thousands of years Baja was populated by the Cochimí and Guachimí peoples who lived a hunter-gatherer existence. The first Europeans arrived in the 1530s and named the peninsula for an island ruled by a black Amazon queen named Califas in the 1510 fantasy book published in Spain called The Adventures of Esplandián. The famous conquistador Hernán Cortés, a decade and a half after subjugating the Aztecs, led an expedition to the southern coast of the peninsula. No real attempts to colonize the region were made for about 150 more years. The colonial Spanish government in Mexico City sent a group of 200 men to settle an area near present-day La Paz on the southern tip of the peninsula. The settlement could not resist the attacks of the natives and was eventually abandoned. Europeans would return permanently near the end of the next decade. In October of 1697 Jesuit priest Juan María de Salvatierra established the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó and the settlement became the administrative center of the territory known as Las Californias. The central authority in Mexico City was very far away and for seven decades the Jesuits were left to their own devices, effectively ruling the entirety of Baja as a separate Jesuit political entity. The region remained sparsely populated for centuries and with very few visitors. Since the time of Konščak in the mid-1700s very little interest was shown in the amazing wall murals the Croatian had discovered, that is, until the 1950s. During this decade the word got out to the rest of the world that these amazing works of art existed and adventurers and explorers, mostly from the US state of California to the north, took an interest in the rock paintings.

What is now a geographical region consisting of a peninsula which is home to two Mexican States – Baja California and Baja California Sur – has always been a backwater. Indeed, Baja California Sur, a seemingly perpetual territory of Mexico only became a state in October of 1974, the last state to be admitted to the Mexican union. Outsiders avoided Baja for most of the peninsula’s history. For thousands of years Baja was populated by the Cochimí and Guachimí peoples who lived a hunter-gatherer existence. The first Europeans arrived in the 1530s and named the peninsula for an island ruled by a black Amazon queen named Califas in the 1510 fantasy book published in Spain called The Adventures of Esplandián. The famous conquistador Hernán Cortés, a decade and a half after subjugating the Aztecs, led an expedition to the southern coast of the peninsula. No real attempts to colonize the region were made for about 150 more years. The colonial Spanish government in Mexico City sent a group of 200 men to settle an area near present-day La Paz on the southern tip of the peninsula. The settlement could not resist the attacks of the natives and was eventually abandoned. Europeans would return permanently near the end of the next decade. In October of 1697 Jesuit priest Juan María de Salvatierra established the Mission of Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó and the settlement became the administrative center of the territory known as Las Californias. The central authority in Mexico City was very far away and for seven decades the Jesuits were left to their own devices, effectively ruling the entirety of Baja as a separate Jesuit political entity. The region remained sparsely populated for centuries and with very few visitors. Since the time of Konščak in the mid-1700s very little interest was shown in the amazing wall murals the Croatian had discovered, that is, until the 1950s. During this decade the word got out to the rest of the world that these amazing works of art existed and adventurers and explorers, mostly from the US state of California to the north, took an interest in the rock paintings.

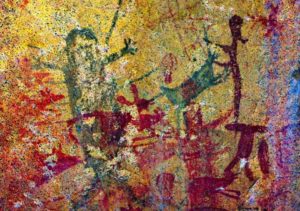

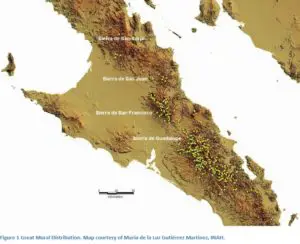

Being mostly sheltered in a desert climate and with little intrusive human traffic the beautiful rock murals are for the most part well-preserved. While outside the central area of the peninsula there are thousands of petroglyphs, those images that are “pecked away” at the rock, the central mountainous area of Baja is the only place where painted rock art exists in abundance. This central mountainous area includes the Guadalupe, San Francisco, San Juan and San Borja ranges. The most common figures painted by the ancient artists include human figures and deer. In addition to these common figures, a variety of other animals exist in the paintings: rabbits, birds, bighorn sheep, fish and snakes. Hunting is a big motif in the artwork. Often, humans are depicted throwing spears and animals are depicted with arrows or darts on them. Most of the figures are drawn in silhouette without any realistic details such as facial features or anatomical parts. Also, geometric patterns such as stripes or wavy lines exist inside the figures. The ancient artists used a palette of primarily red and black, although orange, pink, green and white also exist in the paintings, but to a lesser degree. The pigments were made mostly of minerals sourced locally. The red and reddish-brown color was made by grinding up hematite, an iron compound. The black was made from manganese dioxide. Other colors, which were not as common were made from local plants. Many painted mural sites have designs painted on top of designs, the most being 5 layers deep. Sometimes a rock art site with overpainting is located right next to a blank outcrop or overhang which could have been used but wasn’t. To researchers this phenomenon of painting over designs in certain places indicates two things: The location of these murals is special or even sacred, and many of these sites are very old. As to the age of this artwork, some of it has been dated by sampling organic materials in the pigments on the painted surfaces and by dating bones and charcoal found in the caves. Some of the oldest dates place the beginnings of the murals at around 7,500 years ago, making them the oldest such outdoor art in all the Americas. Archaeologists associate most of the rock art with the Comondú Complex, an archaeological pattern associated with the prehistoric Cochimí people of the central part of the Baja California Peninsula. The complex is known for its unique triangular and serrated projectile points, tubular stone pipes, square-knot netting, coiled basketry and habitation in the rock shelters and overhangs where the mural paintings still survive.

Being mostly sheltered in a desert climate and with little intrusive human traffic the beautiful rock murals are for the most part well-preserved. While outside the central area of the peninsula there are thousands of petroglyphs, those images that are “pecked away” at the rock, the central mountainous area of Baja is the only place where painted rock art exists in abundance. This central mountainous area includes the Guadalupe, San Francisco, San Juan and San Borja ranges. The most common figures painted by the ancient artists include human figures and deer. In addition to these common figures, a variety of other animals exist in the paintings: rabbits, birds, bighorn sheep, fish and snakes. Hunting is a big motif in the artwork. Often, humans are depicted throwing spears and animals are depicted with arrows or darts on them. Most of the figures are drawn in silhouette without any realistic details such as facial features or anatomical parts. Also, geometric patterns such as stripes or wavy lines exist inside the figures. The ancient artists used a palette of primarily red and black, although orange, pink, green and white also exist in the paintings, but to a lesser degree. The pigments were made mostly of minerals sourced locally. The red and reddish-brown color was made by grinding up hematite, an iron compound. The black was made from manganese dioxide. Other colors, which were not as common were made from local plants. Many painted mural sites have designs painted on top of designs, the most being 5 layers deep. Sometimes a rock art site with overpainting is located right next to a blank outcrop or overhang which could have been used but wasn’t. To researchers this phenomenon of painting over designs in certain places indicates two things: The location of these murals is special or even sacred, and many of these sites are very old. As to the age of this artwork, some of it has been dated by sampling organic materials in the pigments on the painted surfaces and by dating bones and charcoal found in the caves. Some of the oldest dates place the beginnings of the murals at around 7,500 years ago, making them the oldest such outdoor art in all the Americas. Archaeologists associate most of the rock art with the Comondú Complex, an archaeological pattern associated with the prehistoric Cochimí people of the central part of the Baja California Peninsula. The complex is known for its unique triangular and serrated projectile points, tubular stone pipes, square-knot netting, coiled basketry and habitation in the rock shelters and overhangs where the mural paintings still survive.

For years everyone from casual adventurers to serious scientists have tried to interpret the meaning of the rock murals. Since early Spanish colonial times the indigenous people living in the area have not taken credit for these interesting works. They, instead, have passed them off as the work of distant ancestors or a race of giants. Because they have no claim to the paintings, local tribes have never been able to interpret their meanings. Serious study of the paintings only began in the 1950s. With the help of journalist Fernando Jordan, Mexican archaeologists Barbro Dahlgren and Javier Romero thoroughly described some of the most prominent rock painting sites in the early 1950s. A formal investigation by the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City soon followed. In the early 1960s American mystery writer and creator of Perry Mason, Erle Stanley Gardner mounted an expedition including the use of helicopters to access the more remote areas and published his findings in Life magazine in an article called “The Case of the Baja California Caves: A Legendary Treasure Left by a Long Lost Tribe” and in a book titled The Hidden Heart of Baja. While publicity and scholarly interest increased in the paintings no one was any closer to interpreting them. There are patterns and conventions recognized in the hundreds of known sites, but little meaning ascribed to the paintings. As mentioned before, hunting is seen as important. Many of the animals seem fat and sturdy. As is customary in other parts of the world, perhaps this has to do with hunting magic. Were ceremonies to ensure a good hunt performed at the base of these murals? One investigator from California named Henry Crosby postulated that perhaps what was depicted on the painting was not the most important aspect of these murals. Many were painted 10-20 feet up or over ledges that dropped a hundred feet, thus

For years everyone from casual adventurers to serious scientists have tried to interpret the meaning of the rock murals. Since early Spanish colonial times the indigenous people living in the area have not taken credit for these interesting works. They, instead, have passed them off as the work of distant ancestors or a race of giants. Because they have no claim to the paintings, local tribes have never been able to interpret their meanings. Serious study of the paintings only began in the 1950s. With the help of journalist Fernando Jordan, Mexican archaeologists Barbro Dahlgren and Javier Romero thoroughly described some of the most prominent rock painting sites in the early 1950s. A formal investigation by the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City soon followed. In the early 1960s American mystery writer and creator of Perry Mason, Erle Stanley Gardner mounted an expedition including the use of helicopters to access the more remote areas and published his findings in Life magazine in an article called “The Case of the Baja California Caves: A Legendary Treasure Left by a Long Lost Tribe” and in a book titled The Hidden Heart of Baja. While publicity and scholarly interest increased in the paintings no one was any closer to interpreting them. There are patterns and conventions recognized in the hundreds of known sites, but little meaning ascribed to the paintings. As mentioned before, hunting is seen as important. Many of the animals seem fat and sturdy. As is customary in other parts of the world, perhaps this has to do with hunting magic. Were ceremonies to ensure a good hunt performed at the base of these murals? One investigator from California named Henry Crosby postulated that perhaps what was depicted on the painting was not the most important aspect of these murals. Many were painted 10-20 feet up or over ledges that dropped a hundred feet, thus  necessitating a ladder or scaffolding technology. Maybe the difficulty of painting had meaning, but it is impossible to tell. Non-conventional theorists look to more otherworldly explanations to the paintings. Some have claimed that the beings in the murals are not humans but extraterrestrials. Some of the figures are life-sized, and the sheer size of the paintings, others believe, point to the old wisdom of the indigenous peoples of the area and what they have been alleging for centuries: that the paintings were made by a long-dead race of giants. All we have to interpret the beautiful art in the middle of the desert are theories and old legends. The wonderful rock paintings of Baja California thus may forever remain a wonderful enigma.

necessitating a ladder or scaffolding technology. Maybe the difficulty of painting had meaning, but it is impossible to tell. Non-conventional theorists look to more otherworldly explanations to the paintings. Some have claimed that the beings in the murals are not humans but extraterrestrials. Some of the figures are life-sized, and the sheer size of the paintings, others believe, point to the old wisdom of the indigenous peoples of the area and what they have been alleging for centuries: that the paintings were made by a long-dead race of giants. All we have to interpret the beautiful art in the middle of the desert are theories and old legends. The wonderful rock paintings of Baja California thus may forever remain a wonderful enigma.

REFERENCES

The Bradshaw Foundation

Crosby, Harry W. The Cave Paintings of Baja California: Discovering the Great Murals of an Unknown People. San Diego: Sunbelt Publications, 1975.

Ewing, Eve. “Calling Down the Rain: Great Mural Art of Baja California, Mexico”. American Indian Rock Art 38:101-128.

Gardner, Erle Stanley. The Hidden Heart of Baja. New York: Morrow, 1962.