Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Get the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/olmecs-we-were-first?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=581

Get the show’s official t-shirt here: https://teespring.com/olmecs-we-were-first?tsmac=store&tsmic=mexico-unexplained&pid=2&cid=581

The year was 1869. In a rather obscure publication printed by the Mexican Society of Geography and Statistics, there appeared a short notice written by a man named José Melgar. It was accompanied by an engraving of what is now known as Monument A at Tres Zapotes. Melgar wrote:

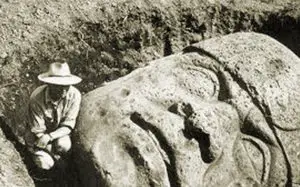

“In 1862, I was in the region of San Andres Tuxtla, a town in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. During my excursions, I learned that a Colossal Head had been unearthed a few years before, in the following manner. Some one-and-a-half leagues from a sugar-cane hacienda, on the western slopes of the Sierra of San Martín, a laborer of the hacienda, while cutting the forest for his field, discovered on the surface of the ground what looked like the bottom of a great iron kettle turned upside down. He notified the owner of the hacienda, who ordered its excavation. And in the place of the kettle was discovered the abovementioned head. It was left in the excavation as one would not think to move it, being of granite and measuring two yards in height with corresponding proportions… On my arrival at the hacienda, I asked the owner of the property where the head was discovered, to take me to look at it. We went, and I was struck with surprise: as a work of art, it is without exaggeration a magnificent sculpture…what astonished me was the Ethiopic type represented. I reflected that there had undoubtedly been Negroes in this country, and that this had been in the first epoch of the world.”

At the time of Melgar’s writings, most of Mexico’s ancient past was still shrouded in mystery. The writing system of the Maya was a century from being deciphered. Many of the major ruins that are familiar today were not even known of or explored thoroughly. The scientific method as applied to archaeology, which was not even a formally recognized discipline, was far from being used. Lost cities in the jungle and rumors of vanished civilizations fueled much speculation about the origins of ancient Mesoamerican peoples. At any given time during the 19th Century, the ancient Mexicans were said to have been ancient Assyrians, prehistoric travelers from India, a lost tribe of Israel, shipwrecked Romans, and, as Melgar, speculated, black Africans. The features on that first Olmec head found in 1858 would puzzle investigators for quite some time. It had a flat and wide nose, full lips and eyes without the characteristic fold found in Native Americans. As the science of archaeology developed and more of these heads were discovered, a clearer view of what would later be called the Olmec Civilization would come about.

At the time of Melgar’s writings, most of Mexico’s ancient past was still shrouded in mystery. The writing system of the Maya was a century from being deciphered. Many of the major ruins that are familiar today were not even known of or explored thoroughly. The scientific method as applied to archaeology, which was not even a formally recognized discipline, was far from being used. Lost cities in the jungle and rumors of vanished civilizations fueled much speculation about the origins of ancient Mesoamerican peoples. At any given time during the 19th Century, the ancient Mexicans were said to have been ancient Assyrians, prehistoric travelers from India, a lost tribe of Israel, shipwrecked Romans, and, as Melgar, speculated, black Africans. The features on that first Olmec head found in 1858 would puzzle investigators for quite some time. It had a flat and wide nose, full lips and eyes without the characteristic fold found in Native Americans. As the science of archaeology developed and more of these heads were discovered, a clearer view of what would later be called the Olmec Civilization would come about.

Melgar’s head would not be known outside of Mexico until 1905 when German archaeologist Eduard Seler and his wife visited it and European newspapers picked up the story. It would be the only colossal Olmec stone head known until the 1925 discovery of the archaeological site of La Venta in the modern Mexican state of Tabasco by a Danish-born archaeologist Frans Blom and his American expedition partner Oliver La Farge from Tulane University. The two did not realize that they had stumbled upon a lost city built by the members of Mexico’s oldest civilization, the Olmecs, and described La Venta as a Maya site.

The term “Olmec” had been around since the 16th Century but was not frequently used and it was not employed the way it is today, to denote “the mother of Mesoamerican civilizations” that existed in the Mexican jungles from around 1200 BC to 400 BC. The term “Olmec” loosely translates to “the rubber people” or “people who live in the land of rubber.” By the 1930s the term began to be used when describing the pre-Maya people of the tropical lowlands who built large civic-ceremonial centers and left behind thousands of intricate artifacts. Matthew Stirling, of the Smithsonian Institution discovered a dated inscription at the site of Tres Zapotes in 1939 that put the city’s heyday centuries before the Classic Maya civilization. By the middle of the 20th Century a more solid picture began to emerge of what is known today as the Olmec civilization centered around three major sites on Mexico’s Gulf Coast: Tres Zapotes, La Venta and San Lorenzo.

The term “Olmec” had been around since the 16th Century but was not frequently used and it was not employed the way it is today, to denote “the mother of Mesoamerican civilizations” that existed in the Mexican jungles from around 1200 BC to 400 BC. The term “Olmec” loosely translates to “the rubber people” or “people who live in the land of rubber.” By the 1930s the term began to be used when describing the pre-Maya people of the tropical lowlands who built large civic-ceremonial centers and left behind thousands of intricate artifacts. Matthew Stirling, of the Smithsonian Institution discovered a dated inscription at the site of Tres Zapotes in 1939 that put the city’s heyday centuries before the Classic Maya civilization. By the middle of the 20th Century a more solid picture began to emerge of what is known today as the Olmec civilization centered around three major sites on Mexico’s Gulf Coast: Tres Zapotes, La Venta and San Lorenzo.

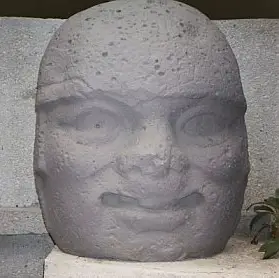

The huge disembodied stone heads are perhaps the most famous hallmarks of the Olmec. There are 17 known Olmec colossal stone heads, the last one discovered in 1994. 10 were uncovered at the site of San Lorenzo, 4 at La Venta, 2 at Tres Zapotes, and one at the small archaeological site of La Cobata in the state of Veracruz. Outside these 17 heads there has been discovered in Takalik Abaj, Guatemala, an altar stone that may have been carved out of a former Olmec head. Possible fragments of colossal heads have been found at San Lorenzo and a much smaller site called San Fernando in the state of Tabasco. Made of basalt, each head measures approximately 5 to 11 feet tall and weighs between 6 to 50 tons. Facial features are similar among the heads: Big lips, rounded cheeks and broad noses. Each head also wears what looks like a helmet or headdress. While each Olmec head is stylistically similar, each piece is unique, almost with a specific personality, which leads researchers to believe that these sculptures were made to represent real rulers. Facial expressions of these heads generally tend to be stern-looking or expressionless. However, the head known  as La Venta Monument 2, with its bunched cheeks and upturned lips, is clearly smiling at the viewer. This is in stark contrast to the first head discovered by Melgar in the 1850s which has an expression of displeasure, almost a frown. A case can also be made that these heads represented rulers because of the sheer amount of resources it took to make them. Quarry people, laborers to move the stones, artists and other assorted workers took a lot of coordination and control, and archaeologists theorize that the monumental sculptures would only have been possible in a highly stratified “top-down” society. Besides, the differences in the appearances of the heads suggest unique individuals and not standard representations of the gods. With no oral history or written records about these heads it is difficult to determine why they were made or how old they actually are. Scholars generally date them to the height of Olmec civilization which was about 900 BC. Some heads are dated by association, by making assumptions about what is found around them. This is often tricky, as many of the heads clearly have been moved from their original locations, possibly several times. As it is impossible to date carved stone, researchers may never be able to determine exact dates of these heads.

as La Venta Monument 2, with its bunched cheeks and upturned lips, is clearly smiling at the viewer. This is in stark contrast to the first head discovered by Melgar in the 1850s which has an expression of displeasure, almost a frown. A case can also be made that these heads represented rulers because of the sheer amount of resources it took to make them. Quarry people, laborers to move the stones, artists and other assorted workers took a lot of coordination and control, and archaeologists theorize that the monumental sculptures would only have been possible in a highly stratified “top-down” society. Besides, the differences in the appearances of the heads suggest unique individuals and not standard representations of the gods. With no oral history or written records about these heads it is difficult to determine why they were made or how old they actually are. Scholars generally date them to the height of Olmec civilization which was about 900 BC. Some heads are dated by association, by making assumptions about what is found around them. This is often tricky, as many of the heads clearly have been moved from their original locations, possibly several times. As it is impossible to date carved stone, researchers may never be able to determine exact dates of these heads.

As mentioned earlier, the stone heads were fashioned from basalt. Researchers have determined that the stones used in all 17 known Olmec heads come from one source: the Sierra de los Tuxtlas in the state of Veracruz. On the southern slopes of the mountains to this day are large boulders made out of what is called Cerro Cintepec basalt which ranges from a light to dark gray color. Those boulders that were seen as “head-shaped” were probably selected for transport off the mountain. Some of these boulders took a journey of almost 100 miles to reach the final destinations of the workshops in the major Olmec urban centers. As the Olmecs had no beasts of burden or no practical use of the wheel, one can only imagine how these gigantic boulders were moved across hills, swamps and waterways. Basalt workshops have been discovered at San Lorenzo where the colossal boulders were most likely transformed into the heads of kings. As the Olmecs had no metal tools, the huge heads were fashioned by the use of stone tools; stone on stone. Sand-like abrasives were found in these workshops, leading archaeologists to believe that in the final stages of sculpting, the heads were smoothed out and finely finished. It must have taken months to make just one head, if not longer, and that does not include transport which may have added additional months to the project.

As mentioned earlier, the stone heads were fashioned from basalt. Researchers have determined that the stones used in all 17 known Olmec heads come from one source: the Sierra de los Tuxtlas in the state of Veracruz. On the southern slopes of the mountains to this day are large boulders made out of what is called Cerro Cintepec basalt which ranges from a light to dark gray color. Those boulders that were seen as “head-shaped” were probably selected for transport off the mountain. Some of these boulders took a journey of almost 100 miles to reach the final destinations of the workshops in the major Olmec urban centers. As the Olmecs had no beasts of burden or no practical use of the wheel, one can only imagine how these gigantic boulders were moved across hills, swamps and waterways. Basalt workshops have been discovered at San Lorenzo where the colossal boulders were most likely transformed into the heads of kings. As the Olmecs had no metal tools, the huge heads were fashioned by the use of stone tools; stone on stone. Sand-like abrasives were found in these workshops, leading archaeologists to believe that in the final stages of sculpting, the heads were smoothed out and finely finished. It must have taken months to make just one head, if not longer, and that does not include transport which may have added additional months to the project.

Outside of mainstream archaeology there exists a separate field of scholarship devoted to the Olmec heads which concentrates on the “out of Africa” theory of the origins of Olmec civilization. Much of the traditional archaeological literature refers to the sculptures as having “Negroid” features. The discoverer of the first Olmec head, José Melgar, described it as having “Ethiopic” features and assumed that a black civilization once visited ancient Mexico. Melgar’s initial impressions are often cited by the African ancestry revisionists. In Clyde Winter’s book, Atlantis in Mexico, and Ivan van Sertima’s, They Came before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America, the authors make the case for an ancient African civilization that  had a kingdom in Mexico a few thousand years ago. Not only do the authors refer to the colossal stone heads and other artwork, they refer to claims of African skeletons being found at some Olmec sites. The evidence of the skeletons has been suppressed, many alternative researchers claim, much like evidence for giants or extraterrestrials has been suppressed. Besides rumors of skeletons and the Olmec heads having “negroid” features, there is very little to this “out of Africa” theory, which gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s during a huge wave of alternative theories about ancient Mexico. The fact that the modern-day Natives of the Tabasco and Veracruz areas still have the same features as those found on the colossal stone heads and lack any African DNA is of little consolation to a researcher inclined to think a certain way. Until more tangible evidence comes to the surface of African contact, most archaeologists are content to call the Olmecs “The Mother Civilization of Ancient Mexico” and see them as something uniquely and altogether Mexican.

had a kingdom in Mexico a few thousand years ago. Not only do the authors refer to the colossal stone heads and other artwork, they refer to claims of African skeletons being found at some Olmec sites. The evidence of the skeletons has been suppressed, many alternative researchers claim, much like evidence for giants or extraterrestrials has been suppressed. Besides rumors of skeletons and the Olmec heads having “negroid” features, there is very little to this “out of Africa” theory, which gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s during a huge wave of alternative theories about ancient Mexico. The fact that the modern-day Natives of the Tabasco and Veracruz areas still have the same features as those found on the colossal stone heads and lack any African DNA is of little consolation to a researcher inclined to think a certain way. Until more tangible evidence comes to the surface of African contact, most archaeologists are content to call the Olmecs “The Mother Civilization of Ancient Mexico” and see them as something uniquely and altogether Mexican.

A colossal Olmec stone head even made it into American popular culture. On August 11, 1991, during the second season of the animated television series The Simpsons, a show aired in which Bart saves Mr. Burns’ life with a blood transfusion. As a token of his appreciation, Mr. Burns gives Bart a huge stone head which he calls, Xtapolapocetl (Pronounced ‘Ex-tapo-lapo-kettle’), “The Olmec god of war.” The family doesn’t like the Olmec head, even though Bart thinks it’s cool, and it ends up in the Simpsons’ basement. The Olmec head would appear in the background in 17 other episodes, in the Simpsons movie and in a video game called, “The Simpsons: Tapped Out.” Just like the real Olmec heads, the Simpsons’ version moves around a lot and it eventually ends up in their yard sale. No one buys it as it appears in later shows. In future episodes we may yet see a colossal Olmec stone head in the basement of America’s favorite cartoon family. Until then, archaeologists anxiously await the discovery of the next real one in the jungles of Mexico.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

America’s First Civilization: Discovering the Olmecs by Michael D. Coe We are an Amazon affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3fHAXxG

Mesoamerica: The Evolution of a Civilization by William T. Sanders and Barbara J. Price. We are an Amazon affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3bieK64

Atlantis in Mexico by Clyde Winters. We are an Amazon affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/362iMyB

They Came Before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient America by Ivan van Sertima We are an Amazon affiliate. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2xUpI3X