Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The year was 1831. Irish-Born Juan Galindo, not yet 30 years old, was traveling along the jungle-lined Usumacinta River. When he got to a severe bend in the river, he noticed hills covered in vegetation and crumbled building stones. His indigenous scouts told him that the place was once the home of a famous ancestor called Bol Menché, but no one knew the name of this lost city. Galindo explored the ruins. As a naturalized citizen of the young Republic of Central America and the military ruler of the Petén region of what is now Guatemala, Galindo took extensive notes on any and all ruins he encountered during his various trips throughout his administrative area. The ruins in the bend of the river located today in the Mexican state of Chiapas were later named Yaxchilán by 20th Century archaeologists, which means “Green Stones” in a local Maya dialect. After the Maya writing system was deciphered to a great extent beginning in the 1950s, the emblem glyph of the site was understood to be read as Siyaj Chan, or “Sky Born” in English. The “Sky Born” city was said to be the capital of a small kingdom called Pa’ Chan, or “Broken Sky.” Juan Galindo wrote about this city now known as Yaxchilán in several articles and letters, with one of his articles published in the London Literary Gazette. In the early 1830s there were many wild theories around about the origins of the people who built the mysterious cities that lay in ruin in the jungles of Mexico and Central America. Through his observations of Maya art – carvings, murals, pottery decorations, etc. – the young military ruler was the first to conclude that the ancestors of the people currently living in the area were the ones who built these once-great cities. This was obvious to him because the current population looked identical to those depicted in the ancient artwork. Galindo would have many more ruined sites to explore and many more theories to ponder as the Republic of Central America granted him one million acres of land in what is now northern Guatemala and Belize. He had a tenuous hold over this claim, though, because some of the land grant overlapped with territorial claims of British Honduras, and the Central American Republic would only let Galindo keep the land if he could settle it and pacify the hostile Lacandon Maya. Juan Galindo went to England to try to iron out his land dispute with the British, but that went nowhere, and he had no clear title to a big chunk of his million acres. He returned to Central America and resumed his role as a military leader, eventually dying in 1840 during a civil war in the republic. Galindo left behind many written observations about the various ruins he surveyed, including the first written accounts of Yaxchilán mentioned earlier. As he was a keen observer of the human form represented in Maya art, he was the first to make note of the seemingly powerful female figures in the many carvings throughout Yaxchilán. Today we know these ancient Maya queens as Lady Pacal, Lady Xoc and Lady Evening-Star.

The year was 1831. Irish-Born Juan Galindo, not yet 30 years old, was traveling along the jungle-lined Usumacinta River. When he got to a severe bend in the river, he noticed hills covered in vegetation and crumbled building stones. His indigenous scouts told him that the place was once the home of a famous ancestor called Bol Menché, but no one knew the name of this lost city. Galindo explored the ruins. As a naturalized citizen of the young Republic of Central America and the military ruler of the Petén region of what is now Guatemala, Galindo took extensive notes on any and all ruins he encountered during his various trips throughout his administrative area. The ruins in the bend of the river located today in the Mexican state of Chiapas were later named Yaxchilán by 20th Century archaeologists, which means “Green Stones” in a local Maya dialect. After the Maya writing system was deciphered to a great extent beginning in the 1950s, the emblem glyph of the site was understood to be read as Siyaj Chan, or “Sky Born” in English. The “Sky Born” city was said to be the capital of a small kingdom called Pa’ Chan, or “Broken Sky.” Juan Galindo wrote about this city now known as Yaxchilán in several articles and letters, with one of his articles published in the London Literary Gazette. In the early 1830s there were many wild theories around about the origins of the people who built the mysterious cities that lay in ruin in the jungles of Mexico and Central America. Through his observations of Maya art – carvings, murals, pottery decorations, etc. – the young military ruler was the first to conclude that the ancestors of the people currently living in the area were the ones who built these once-great cities. This was obvious to him because the current population looked identical to those depicted in the ancient artwork. Galindo would have many more ruined sites to explore and many more theories to ponder as the Republic of Central America granted him one million acres of land in what is now northern Guatemala and Belize. He had a tenuous hold over this claim, though, because some of the land grant overlapped with territorial claims of British Honduras, and the Central American Republic would only let Galindo keep the land if he could settle it and pacify the hostile Lacandon Maya. Juan Galindo went to England to try to iron out his land dispute with the British, but that went nowhere, and he had no clear title to a big chunk of his million acres. He returned to Central America and resumed his role as a military leader, eventually dying in 1840 during a civil war in the republic. Galindo left behind many written observations about the various ruins he surveyed, including the first written accounts of Yaxchilán mentioned earlier. As he was a keen observer of the human form represented in Maya art, he was the first to make note of the seemingly powerful female figures in the many carvings throughout Yaxchilán. Today we know these ancient Maya queens as Lady Pacal, Lady Xoc and Lady Evening-Star.

Unlike Aztec civilization, which was intact when the Spanish arrived, Classic Maya civilization, known for its magnificent art and architecture, mysteriously ended centuries before Europeans arrived in the New World. Fortunately, the ancient Maya had very sophisticated writing and calendar systems which, when combined with beautiful illustrations, tell the tales of kings and queens and exotic happenings from a time long ago. For a detailed exploration of the Maya writing system, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 16: https://mexicounexplained.com//writing-ancient-maya-history-words/ With the decipherment of Maya writing scholars have been able to piece together elaborate histories of this complex jungle society. With most Maya glyphs interpreted, researchers have a clearer picture of the lives of the rulers of these ancient kingdoms. Carved on monuments throughout their cities, Maya rulers celebrated their victories over other city-states and described important milestones or events in their reigns, to further legitimize their rule in the eyes of their subjects. The archaeological site of Yaxchilán is especially rich in dynastic history with inscriptions going back to the city’s founding in the year 359 AD under King Yopaat B’alam I and going unbroken to the reign of a king known to scholars as K’inich Tatb’u Skull III. K’inich Tatb’u Skull III was the 17th and last king of Yaxchilán. The last inscription with his name on it at the site dates to 812 AD.

Among the long line of kings at Yaxchilán we see some of the most powerful female rulers the Maya world had ever seen. While various consorts of kings and other female relatives merit passing mention on the city’s monuments, the first one of notable prominence is known as Lady Pacal. This woman is not related to nor should she be confused with Lord Pacal or Pacal the Great from the city of Palenque. The word pacal means “shield” in the local Maya dialect. So, in English, this queen would have been known as “Lady Shield.” Apparently, she was from a very wealthy and powerful local family. Modern people would say that Lady Pacal also had, “good genes.” The noble queen died in the year 705 AD after reaching her 98th birthday. She would pass these good genes on to her son, King Shield-Jaguar who would live to his mid-90s ruling Yaxchilán for over 60 years. The long life of Lady Pacal could not have been without enormous influence on the city’s politics. In perhaps one of her biggest political moves, Lady Pacal ensured that one of her female relatives, perhaps a younger sister or cousin, married her son, Shield-Jaguar, the heir to the throne. This influential Maya woman’s name was Lady Xoc.

Among the long line of kings at Yaxchilán we see some of the most powerful female rulers the Maya world had ever seen. While various consorts of kings and other female relatives merit passing mention on the city’s monuments, the first one of notable prominence is known as Lady Pacal. This woman is not related to nor should she be confused with Lord Pacal or Pacal the Great from the city of Palenque. The word pacal means “shield” in the local Maya dialect. So, in English, this queen would have been known as “Lady Shield.” Apparently, she was from a very wealthy and powerful local family. Modern people would say that Lady Pacal also had, “good genes.” The noble queen died in the year 705 AD after reaching her 98th birthday. She would pass these good genes on to her son, King Shield-Jaguar who would live to his mid-90s ruling Yaxchilán for over 60 years. The long life of Lady Pacal could not have been without enormous influence on the city’s politics. In perhaps one of her biggest political moves, Lady Pacal ensured that one of her female relatives, perhaps a younger sister or cousin, married her son, Shield-Jaguar, the heir to the throne. This influential Maya woman’s name was Lady Xoc.

The story of Lady Xoc, Queen of Yaxchilán, is illustrated on what is known on Structure 23 in the heart of the civic-ceremonial center of the city. A series of carved lintels, or supports above building entrances, demonstrate to the world Lady Xoc’s importance in this powerful jungle kingdom. She is shown in several scenes engaging in ritualistic and ceremonial practices at this building. The depiction of a female as the principal participant in ritual is extremely rare to see in ancient Maya art, and this is why researchers believe that Lady Xoc was one of the most important female nobles in the Maya world. The carvings on Building 23 of this famous queen were most likely highly political in nature. Lady Xoc was King Shield-Jaguar’s first wife, but not the mother of his successor. The queen did not bear him any sons, or at least none who survived to rule the kingdom. The marriage to Lady Xoc did solidify Shield-Jaguar’s place on the throne, however, because she came from the most influential family at Yaxchilán. In their book A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya, Maya scholars Linda Schele and David Freidel theorized that even though Lady Xoc would not bear the king a son to succeed him, King Shield-Jaguar wanted to show publicly that Lady Xoc was still important, so as to appease her powerful family. It must have worked, because even though Shield-Jaguar had other wives, including one who would bear him an heir, his rule lasted over 60 years and his reign was uncontested.

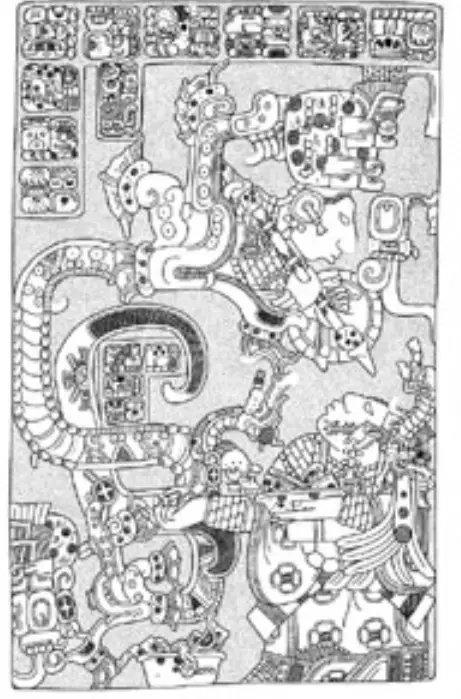

The carved lintels depicting Lady Xoc are some of the most spectacular examples of ancient Maya carvings yet known. On Lintel 24 King Shield-Jaguar holds a flaming torch above Lady Xoc as she performs the important ritual of bloodletting by pulling a rope laced with stingray spines through a hole in her tongue. This carving has a date marking its dedication: October 28, 709. Another lintel shows Lady Xoc holding the king’s helmet and shield, helping Shield-Jaguar prepare for an important battle. The carving known as Lintel 25 is perhaps the most curious and the most beautiful. It shows Lady Xoc calling forth the Vision Serpent which is rising from a bowl. The queen is shown looking at the serpent, and in its mouth emerges the first king of Yaxchilán, Yopaat B’alam. Researchers believe that this king is Lady Xoc’s ancestor and this is one of the reasons why she is engaging in a ritual reserved almost exclusively for noble Maya men. Maya historians also believe that Building 23, the site of these elaborate carvings, was the personal property of Lady Xoc, as indicated by the structure’s inscriptions. In the ancient Maya world, the main buildings of the civic-ceremonial centers such as Building 23 were said to belong to the gods and not to individual people. For some reason, this important building in the very center of Yaxchilán was the personal property of the queen which was unheard of in the Maya world. Researchers are at a loss to understand why, but it surely indicates this woman’s important role in the kingdom’s history.

The carved lintels depicting Lady Xoc are some of the most spectacular examples of ancient Maya carvings yet known. On Lintel 24 King Shield-Jaguar holds a flaming torch above Lady Xoc as she performs the important ritual of bloodletting by pulling a rope laced with stingray spines through a hole in her tongue. This carving has a date marking its dedication: October 28, 709. Another lintel shows Lady Xoc holding the king’s helmet and shield, helping Shield-Jaguar prepare for an important battle. The carving known as Lintel 25 is perhaps the most curious and the most beautiful. It shows Lady Xoc calling forth the Vision Serpent which is rising from a bowl. The queen is shown looking at the serpent, and in its mouth emerges the first king of Yaxchilán, Yopaat B’alam. Researchers believe that this king is Lady Xoc’s ancestor and this is one of the reasons why she is engaging in a ritual reserved almost exclusively for noble Maya men. Maya historians also believe that Building 23, the site of these elaborate carvings, was the personal property of Lady Xoc, as indicated by the structure’s inscriptions. In the ancient Maya world, the main buildings of the civic-ceremonial centers such as Building 23 were said to belong to the gods and not to individual people. For some reason, this important building in the very center of Yaxchilán was the personal property of the queen which was unheard of in the Maya world. Researchers are at a loss to understand why, but it surely indicates this woman’s important role in the kingdom’s history.

While Lady Xoc would not produce an heir to the Yaxchilán throne, Lady Evening-Star would. The marriage of King Shield-Jaguar to Lady Evening-Star was an international affair. She was a princess, the daughter of the king of Calakmul, a Maya city-state located over 100 miles to the northeast of Yaxchilán. The marriage not only brought peace between the rival kingdoms of Yaxchilán and Calakmul, it produced the male heir that King Shield-Jaguar needed. Lady Evening-Star was in her early 20s and the Yaxchilán king was 61 years old when future king Bird-Jaguar the Great was born. The queen kept close to her family and her own brother would rule the kingdom of Calakmul. With the death of King Shield-Jaguar in his mid-90s, the son of Lady Evening-Star was assumed to accede to the throne of Yaxchilán, but the history written on the stones shows the transition of power was difficult. For almost 10 years Yaxchilán had either no king or several pretenders to the throne trying to take power. Some theorize that the city was a subject state of a neighboring kingdom during this power vacuum, and other theories have Lady Evening-Star ruling as a kind of regent, holding the throne for her son. One can only imagine the politics involved here or what position the queen was in as a foreigner at Yaxchilán with few allies. The fact that Lady Evening-Star was a princess from a foreign bloodline may have caused the old nobility of Yaxchilán to question her son’s right to rule. In the end, Lady Evening-Star would never be a dowager queen as she would die a few months before her son became king. The nature of her death is unknown, but she died at the age of 47 in the year 751. Her son King Bird-Jaguar would rule Yaxchilán from the years 752 to 758 a time of great prosperity for the city with many monumental building projects completed during this time. Within a generation, though, the building would stop and like so many other Maya city-states Yaxchilán would collapse and fade into obscurity. What’s left is not just the crumbling buildings in the jungle but bits and pieces of the fascinating stories of the people who lived there. Many stories are yet to be told.

While Lady Xoc would not produce an heir to the Yaxchilán throne, Lady Evening-Star would. The marriage of King Shield-Jaguar to Lady Evening-Star was an international affair. She was a princess, the daughter of the king of Calakmul, a Maya city-state located over 100 miles to the northeast of Yaxchilán. The marriage not only brought peace between the rival kingdoms of Yaxchilán and Calakmul, it produced the male heir that King Shield-Jaguar needed. Lady Evening-Star was in her early 20s and the Yaxchilán king was 61 years old when future king Bird-Jaguar the Great was born. The queen kept close to her family and her own brother would rule the kingdom of Calakmul. With the death of King Shield-Jaguar in his mid-90s, the son of Lady Evening-Star was assumed to accede to the throne of Yaxchilán, but the history written on the stones shows the transition of power was difficult. For almost 10 years Yaxchilán had either no king or several pretenders to the throne trying to take power. Some theorize that the city was a subject state of a neighboring kingdom during this power vacuum, and other theories have Lady Evening-Star ruling as a kind of regent, holding the throne for her son. One can only imagine the politics involved here or what position the queen was in as a foreigner at Yaxchilán with few allies. The fact that Lady Evening-Star was a princess from a foreign bloodline may have caused the old nobility of Yaxchilán to question her son’s right to rule. In the end, Lady Evening-Star would never be a dowager queen as she would die a few months before her son became king. The nature of her death is unknown, but she died at the age of 47 in the year 751. Her son King Bird-Jaguar would rule Yaxchilán from the years 752 to 758 a time of great prosperity for the city with many monumental building projects completed during this time. Within a generation, though, the building would stop and like so many other Maya city-states Yaxchilán would collapse and fade into obscurity. What’s left is not just the crumbling buildings in the jungle but bits and pieces of the fascinating stories of the people who lived there. Many stories are yet to be told.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael D. The Maya. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015. We are Amazon affiliates. You can purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3cB2lMF

Schele, Linda and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 1992. We are Amazon affiliates. You can purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3j3IM25