Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

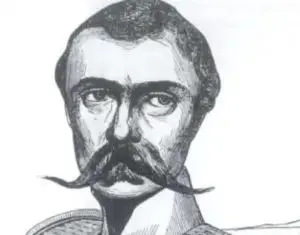

In the small town of Guerrero in the Mexican state of Nuevo León, a rather unassuming man issued a proclamation. He was tired of the controlling central authority in Mexico City headed by dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna and claimed that his family’s vast land holdings in the northern part of the country had been taken over by Mexican centralists, who, like Santa Anna, had no respect for the 1824 Constitution of Mexico which guaranteed states’ rights and more local autonomy in a more federalist system. The man making the proclamation was Antonio Canales Rosillo and the date was November 3, 1838. Little did he know that the simple declaration, which roused the independent-minded people who heard it, would lead Canales to play an important role in a new national experiment named in honor of the river flowing less than 20 miles from that speech. In 13 months’ time, Canales would be the commander-in-chief and one of the founding fathers of the new Republic of the Rio Grande, or in Spanish, La República del Río Grande, carrying the bold red, white and black flag emblazoned with three stars which stood for three breakaway states: Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

In the small town of Guerrero in the Mexican state of Nuevo León, a rather unassuming man issued a proclamation. He was tired of the controlling central authority in Mexico City headed by dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna and claimed that his family’s vast land holdings in the northern part of the country had been taken over by Mexican centralists, who, like Santa Anna, had no respect for the 1824 Constitution of Mexico which guaranteed states’ rights and more local autonomy in a more federalist system. The man making the proclamation was Antonio Canales Rosillo and the date was November 3, 1838. Little did he know that the simple declaration, which roused the independent-minded people who heard it, would lead Canales to play an important role in a new national experiment named in honor of the river flowing less than 20 miles from that speech. In 13 months’ time, Canales would be the commander-in-chief and one of the founding fathers of the new Republic of the Rio Grande, or in Spanish, La República del Río Grande, carrying the bold red, white and black flag emblazoned with three stars which stood for three breakaway states: Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas.

Historian Milton Lindheim in his 1964 book The Republic of the Rio Grande: Texans in Mexico, 1839-40, the author writes this about commander-in-chief Antonio Canales. He was, “lawyer by profession, a rebel leader by preference, had prowled the borderlands from Boca Chica westward, strewing seditious doctrines. He was a strange, erratic person: not handsome, but strong of body, passions, and mind; adventurous and skilled in horsemanship; cowing weaker men and yielding to stronger; entrancing the masses with glib talk, apparent recklessness, and masterly propaganda.” Like many people on the fringes of empires, or those who were born and bred in areas devoid of formalized central political control, Canales and his compatriots just wanted to be left alone to live independent lives. His messages against Santa Anna’s highly centralized government found many  sympathetic ears in the remote north of Mexico and people were further energized by the success of rebel province of Texas in its attempts to break away from Mexico City. While Canales was good at stirring up the feelings of discontent, he knew that something needed to be formalized if the people in his region would ever be like Texas. Two months after his proclamation, in January of 1839, Antonio Canales called for a convention at the building of the Justice of the Peace in Laredo to figure out how to organize against the central powers in Mexico City. The Mexican federalist constitution of 1824 was recognized at this convention and Canales volunteered to raise an army to help defend the 1824 constitution against the centralists and to ensure autonomy of the northern areas of Mexico. The Laredo convention of January 1839 did not go so far as to declare the independence of a new nation, but did lay the foundations for one. Canales got busy immediately and had no trouble finding new recruits for his new army: Mexican cowboys, Indian warriors and an assortment of Anglo and Mexican Texans made up the new federalist fighting force. Beyond political concerns, all men participating in the new army would receive $22.00 a month pay and any share of any loot. Commander-in-Chief Canales, who had abhorred all central authority, even that of the Catholic Church, had intended to use the property from churches and convents to pay what he promised the soldiers. Canales, seasoned in battle during the Apache Wars of his early adulthood, was no stranger to war and his troops looked up to him as an excellent officer. By the fall of 1839 he had amassed a large force and it was ready for its first battle against the Mexican centralists.

sympathetic ears in the remote north of Mexico and people were further energized by the success of rebel province of Texas in its attempts to break away from Mexico City. While Canales was good at stirring up the feelings of discontent, he knew that something needed to be formalized if the people in his region would ever be like Texas. Two months after his proclamation, in January of 1839, Antonio Canales called for a convention at the building of the Justice of the Peace in Laredo to figure out how to organize against the central powers in Mexico City. The Mexican federalist constitution of 1824 was recognized at this convention and Canales volunteered to raise an army to help defend the 1824 constitution against the centralists and to ensure autonomy of the northern areas of Mexico. The Laredo convention of January 1839 did not go so far as to declare the independence of a new nation, but did lay the foundations for one. Canales got busy immediately and had no trouble finding new recruits for his new army: Mexican cowboys, Indian warriors and an assortment of Anglo and Mexican Texans made up the new federalist fighting force. Beyond political concerns, all men participating in the new army would receive $22.00 a month pay and any share of any loot. Commander-in-Chief Canales, who had abhorred all central authority, even that of the Catholic Church, had intended to use the property from churches and convents to pay what he promised the soldiers. Canales, seasoned in battle during the Apache Wars of his early adulthood, was no stranger to war and his troops looked up to him as an excellent officer. By the fall of 1839 he had amassed a large force and it was ready for its first battle against the Mexican centralists.

On October 3, 1839, exactly 11 months after his proclamation in Guerrero that started it all, Canales and his men laid siege to the centralist stronghold at Estancia de Mier, located on what is now the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. During the battle, the Mexican centralists were holed up in a hacienda and eventually surrendered to two Anglo-Texans who had led the charge, Reuben Ross and Samuel Jordan, two men who had been recruited to the cause by Canales while he was drumming up support among Texans and enlisting men in San Antonio. Known in history as The Battle of Mier, the showdown at the hacienda eventually led to a surrender and prisoners of war quickly converted into federalists. Canales’ force thus gained 60 new men and 4 heavy cannons. After this battle, Canales, who was then being called “General Canales,” was seen as a hero in the North and as a result of his victory at Estancia de Mier, money, material support and fresh recruits poured in.

Canales’ next move was a tactical error. Instead of using his momentum to propel himself to further victories, Canales camped out at Estancia de Mier for 40 days. Many of his men were eager to fight and when Canales gave no indication that he would be moving after a few weeks, 50 Texans deserted him and went back across the Rio Grande to Texas. In the middle of November of 1839, Antonio Canales decided to attack the town of Matamoros where a garrison loyal to Santa Anna and the centralists had dug themselves in. It took weeks for him to get there with his army and when he arrived he found that he was outmanned and outgunned. Instead of risking certain defeat, Canales decided to march on Monterrey as he had heard that centralist General Mariano Arista did not have the same numbers as the force at Matamoros and perhaps it would be easy to capture the city of Monterrey. General Arista proved to be a formidable foe and defended Monterrey better than Canales anticipated. On the night of December 27, 1839, Arista sent spies into the Canales camp and successfully bribed 160 of the federalists to switch sides and abandon the camp. In the morning, when he had found a big chunk of his fighting force gone, Canales decided to cross the Rio Grande in retreat. Many more people deserted him, especially the Anglo Texans who grew to see Canales as an inept military leader.

Canales’ next move was a tactical error. Instead of using his momentum to propel himself to further victories, Canales camped out at Estancia de Mier for 40 days. Many of his men were eager to fight and when Canales gave no indication that he would be moving after a few weeks, 50 Texans deserted him and went back across the Rio Grande to Texas. In the middle of November of 1839, Antonio Canales decided to attack the town of Matamoros where a garrison loyal to Santa Anna and the centralists had dug themselves in. It took weeks for him to get there with his army and when he arrived he found that he was outmanned and outgunned. Instead of risking certain defeat, Canales decided to march on Monterrey as he had heard that centralist General Mariano Arista did not have the same numbers as the force at Matamoros and perhaps it would be easy to capture the city of Monterrey. General Arista proved to be a formidable foe and defended Monterrey better than Canales anticipated. On the night of December 27, 1839, Arista sent spies into the Canales camp and successfully bribed 160 of the federalists to switch sides and abandon the camp. In the morning, when he had found a big chunk of his fighting force gone, Canales decided to cross the Rio Grande in retreat. Many more people deserted him, especially the Anglo Texans who grew to see Canales as an inept military leader.

On January 17, 1840 a new convention was held at Rancho de Oreveña just outside of Laredo. Many members of the northern Mexican families of influence were there along with others who were interested in creating a new nation out of the Mexican states of Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas. At that time, the territories of the Mexican states of Coahuila and Tamaulipas had spanned the Rio Grande and bordered with the Republic of Texas at the Nueces River. Because the Rio Grande ran through the territory of this new political entity, the country would be called The Republic of the Rio Grande. There were no representatives from the official governments of the three breakaway states at the convention and the new country was not immediately recognized by anyone other than the people at the convention and some sympathetic Mexican citizens. The convention  participants knew that they had to formalize things as quickly as they could, so they immediately named to the position of President of the Republic of the Rio Grande a man named Jesús Cárdenas, a lawyer and former low-level politician from the state of Tamaulipas whose nickname was El Tecolote, or “The Owl,” because of his enormous eyeglasses. The Secretary of State of the new republic was José Carbajal, a Tejano born in San Antonio who, as a teenage boy, was mentored by Stephen F. Austin – the so-called “Father of Texas” – and even spent some of his early adulthood in Kentucky and Virginia converting to Protestantism in the process. In addition to President and Secretary of State, the new republic had three councilors representing each of the breakaway states. There was a role for Antonio Canales to play in the new country as well. He was made Secretary of War and was given the title Commander-in-Chief of the Rio Grande military. Ten days after the convention at the ranch outside of Laredo everything was formalized at the town of Guerrero with official oath swearing and an inauguration ceremony. The motto of the Republic of the Rio Grande would be “Dios, Libertad y Convención,” in English, “God, Liberty, and Convention.” In addition to the red, white and black flag with the three stars, the new nation also had an official newspaper, Correo del Rio Bravo del Norte. It seemed like the young republic was off to a great start, but with all new countries formed out of breakaway territories, there were many battles to be fought to insure the country’s survival.

participants knew that they had to formalize things as quickly as they could, so they immediately named to the position of President of the Republic of the Rio Grande a man named Jesús Cárdenas, a lawyer and former low-level politician from the state of Tamaulipas whose nickname was El Tecolote, or “The Owl,” because of his enormous eyeglasses. The Secretary of State of the new republic was José Carbajal, a Tejano born in San Antonio who, as a teenage boy, was mentored by Stephen F. Austin – the so-called “Father of Texas” – and even spent some of his early adulthood in Kentucky and Virginia converting to Protestantism in the process. In addition to President and Secretary of State, the new republic had three councilors representing each of the breakaway states. There was a role for Antonio Canales to play in the new country as well. He was made Secretary of War and was given the title Commander-in-Chief of the Rio Grande military. Ten days after the convention at the ranch outside of Laredo everything was formalized at the town of Guerrero with official oath swearing and an inauguration ceremony. The motto of the Republic of the Rio Grande would be “Dios, Libertad y Convención,” in English, “God, Liberty, and Convention.” In addition to the red, white and black flag with the three stars, the new nation also had an official newspaper, Correo del Rio Bravo del Norte. It seemed like the young republic was off to a great start, but with all new countries formed out of breakaway territories, there were many battles to be fought to insure the country’s survival.

The new nation’s president Jesús Cárdenas, in a letter to Antonio Navarro of San Antonio, admitted that victory and survival rested, not on home-grown efforts, but “upon the support which we ought to expect to receive from the Government of Texas.” The political elites in the relatively young Republic of Texas had watched this all unfold with more than a mild dose of curiosity. In 1840 the president of Texas was Mirabeau B. Lamar. In the early days of the Rio Grande Republic, Commander-in-Chief Antonio Canales met with Lamar in San Antonio to discuss official support for their cause. The President of Texas balked. Lamar unofficially encouraged Texan support of the new Republic of the Rio Grande and quietly urged Texans to aid the new country with money, arms and through volunteering, either in the military or in some other way. Lamar saw Texas as being caught between a rock and a hard place with regard to formal recognition of the new republic. On one hand he thought it helpful to have a buffer state in between Texas and Mexico just in case Mexico decided to invade Texas again to try to take it back. On the other hand President Lamar knew that if Texas formally recognized the Republic of the Rio Grande, the Mexican government would be angered and would never fully recognize Texas’ independence from Mexico. Texas took a “sit back and wait” attitude to see what would ultimately become of the new nation on its western border.

As mentioned earlier, the new nation’s independence from Mexico had to be earned. The first major battle of the forces of the new republic under Canales occurred at Santa Rita de Morelos in late March of 1840. On the Mexican side was Canales’ former foe from Monterrey, General Mariano Arista. Arista had eighteen hundred men, Canales had barely four hundred. One of Canales’ commanders, a man named Antonio Zapata, was captured, tortured and executed after refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to Mexico. The defeat at Santa Rita was a major blow to the new nation’s army and caused Canales to retreat back to the town of San Fernando where he ultimately engaged with Mexican General Arista again and was heartily defeated, losing almost 250 men. With the 150 men remaining, Canales retreated again, crossed the Rio Grande and headed for Texas where he would regroup. At this time, the administrative branch of the government of the Republic of the Rio Grande had moved out of Laredo and operated “in exile” in Victoria, Texas.

As mentioned earlier, the new nation’s independence from Mexico had to be earned. The first major battle of the forces of the new republic under Canales occurred at Santa Rita de Morelos in late March of 1840. On the Mexican side was Canales’ former foe from Monterrey, General Mariano Arista. Arista had eighteen hundred men, Canales had barely four hundred. One of Canales’ commanders, a man named Antonio Zapata, was captured, tortured and executed after refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to Mexico. The defeat at Santa Rita was a major blow to the new nation’s army and caused Canales to retreat back to the town of San Fernando where he ultimately engaged with Mexican General Arista again and was heartily defeated, losing almost 250 men. With the 150 men remaining, Canales retreated again, crossed the Rio Grande and headed for Texas where he would regroup. At this time, the administrative branch of the government of the Republic of the Rio Grande had moved out of Laredo and operated “in exile” in Victoria, Texas.

While in Texas, Canales met up again with Colonel Samuel Jordan who had fought with him in October of the previous year at Estancia de Mier. In the town of San Patricio, Jordan assembled a contingent of nearly 800 men, almost half of them Anglo Texans and about 10% of them Native Americans. Emboldened and refreshed, the new army of the Republic of the Rio Grande crossed its namesake river and had several small victories. Canales and Jordan were able to recapture Laredo and Guerrero and sacked Ciudad Victoria, installing military administrators in every town they wrested from the Mexicans. After the sacking of Ciudad Victoria, Canales set his sights on Saltillo where a Mexican general by the name of Montoya had quartered his troops. In the famous Battle of Saltillo on October 25th 1840, the Mexican troops surrounded Colonel Jordan who was holed up in a hacienda with his men, mostly Anglo Texans. During the daylong siege of the hacienda, the Mexicans lost almost 400 men while the Republic of the Rio Grande lost only 5. The forces under Canales and Jordan retreated once again in defeat. Jordan would return to Texas and in June the next year would commit suicide.

After the defeat at Saltillo, Commander-in-Chief Antonio Canales saw the handwriting on the wall. In November of 1840, Canales entered into secret negotiations with his recurring adversary, General Mariano Arista, for his surrender and to accept a commission in Santa Anna’s army as an officer. Days after Canales’ surrender, President Cárdenas and all of the other officials of the new nation surrendered to the Mexican authorities at Laredo. In exchange for an oath of allegiance to Mexico, clemency was granted to all participants in what was seen as a mere rebel movement and no property was confiscated or reparations paid under the conditions of the surrender. It was all over rather quickly and cleanly. Within the span of a mere 11 months, the fledgling Republic of the Rio Grande was born, lived and died.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

The Republic of the Rio Grande: Texans in Mexico, 1839-40 by Milton Lindheim