Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was September 12, 1997. Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo stood alongside Ireland’s ambassador to Mexico, Sean O’Huighinn, in a small plaza in the southwestern Mexico City. In a speech full of emotion, President Zedillo said:

The date was September 12, 1997. Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo stood alongside Ireland’s ambassador to Mexico, Sean O’Huighinn, in a small plaza in the southwestern Mexico City. In a speech full of emotion, President Zedillo said:

“One hundred and fifty years ago, here in San Ángel, members of the St. Patrick’s Battalion were executed for following their consciences. They were martyred for adhering to the highest ideals, and today we honor their memory. In the name of the people of Mexico, I salute today the people of Ireland and express my eternal gratitude. While we honor the memory of the Irish who gave their lives for Mexico and for human dignity, we also honor our own commitment to cherish their ideals, and to always defend the values for which they occupy a place of honor in our history.”

A person at this ceremony at San Jacinto Plaza then read a list of names. Among those names was John Patrick Riley, an Irish-born American who served in the US Army but deserted in 1846 right before the onset of the Mexican War. Riley was born Sean Patrick O’Riley in Clifden, County Galway, Ireland in either 1817 or 1818. He was a soldier in the British Army before emigrating to Canada at the beginning of the Irish Potato Famine in 1845. Later that year he arrived in Michigan and enlisted in the US Army. He served in Company K of the 5th US Infantry Regiment and was stationed in Texas. Together with fellow Irish-born soldier Patrick Dalton, Riley deserted the US Army and crossed the Rio Grande at Matamoros.

Riley and Dalton were not the only US military men of Irish roots to flee the United States and cross the border into Mexico. There were many reasons for Irish desertion at this time. The newly arrived Irish immigrants who immediately enlisted in the US Army for mostly economic reasons, escaping poverty at home, were often mistreated by native-born Americans who looked down on them. The fact that the vast majority of these new Irish recruits were Catholic also played a role as they were forced to attend Protestant church services in the military. Likewise, many of these new immigrants were not used to the harsh discipline of army life, as many had been small farmers back in their homeland. Deserters often made the overland trip to Mexico and a freer life in a Catholic country that didn’t mind having them.

When war with Mexico began, Riley and other deserters found themselves in what should have been considered enemy territory. In the early days of the war, Mexican government propaganda was already targeting American soldiers who had become disillusioned with the US military by offering anyone who would defect enlistment bonuses, good pay and promises of officer positions and land grants after the war. In early May of 1846, during the Siege of Fort Texas, Riley and a company of 48 Irish expatriates manned the Mexican artillery. They fought valiantly, but the victory went to the Americans and the Mexicans regrouped. Soon after, Mexican General Pedro de Ampudia gave John Riley the rank of Lieutenant and gave him the task of organizing the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, or in Spanish, El Batallón de San Patricio. Over the course of a few months, the San Patricios grew to almost 200 men and included various other foreigners, among them Germans, Swiss, Poles, Italians, Canadians, English and even a few escaped slaves from the American South. Very few of the battalion’s members were actual US citizens, although there were some native-born American deserters who could not tolerate serving under General Zachary Taylor. The military unit remained overwhelmingly Irish, however, and earned the nickname from Mexicans “Los Colorados,” or “The Reddish Ones” due to the preponderance of ruddy complexions and red hair among the men.

When war with Mexico began, Riley and other deserters found themselves in what should have been considered enemy territory. In the early days of the war, Mexican government propaganda was already targeting American soldiers who had become disillusioned with the US military by offering anyone who would defect enlistment bonuses, good pay and promises of officer positions and land grants after the war. In early May of 1846, during the Siege of Fort Texas, Riley and a company of 48 Irish expatriates manned the Mexican artillery. They fought valiantly, but the victory went to the Americans and the Mexicans regrouped. Soon after, Mexican General Pedro de Ampudia gave John Riley the rank of Lieutenant and gave him the task of organizing the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, or in Spanish, El Batallón de San Patricio. Over the course of a few months, the San Patricios grew to almost 200 men and included various other foreigners, among them Germans, Swiss, Poles, Italians, Canadians, English and even a few escaped slaves from the American South. Very few of the battalion’s members were actual US citizens, although there were some native-born American deserters who could not tolerate serving under General Zachary Taylor. The military unit remained overwhelmingly Irish, however, and earned the nickname from Mexicans “Los Colorados,” or “The Reddish Ones” due to the preponderance of ruddy complexions and red hair among the men.

Much has been written about the flag of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion. It has been described in several ways by several sources leading some scholars to believe there were a few different versions of the flag. A US soldier described it thus: “They had a beautiful green silk banner that waved over their heads; on it glittered a silver cross and a golden harp, embroidered by the hands of the fair nuns of San Luis Potosí.” John Riley himself mentioned the flag in correspondence back home. He wrote: “In all my letter, I forgot to tell you under what banner we fought so bravely. It was that glorious emblem of native rights, that being the banner which should have floated over our native soil many years ago, it was St. Patrick, the Harp of Erin, the Shamrock upon a green field.” Another account stated that the flag displayed an Irish harp along with the Mexican coat of arms. Underneath the Arms of Mexico there was a scroll reading, “Freedom for the Mexican Republic.” Underneath the harp was the motto in Gaelic “Erin go Brágh,” Ireland forever. On the other side of the flag Saint Patrick was depicted holding a pastoral staff and standing on a serpent. The Patricios may have used different flags for their infantry and artillery units, and another flag may have been used after they were reorganized in the later days of the Mexican War.

Much has been written about the flag of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion. It has been described in several ways by several sources leading some scholars to believe there were a few different versions of the flag. A US soldier described it thus: “They had a beautiful green silk banner that waved over their heads; on it glittered a silver cross and a golden harp, embroidered by the hands of the fair nuns of San Luis Potosí.” John Riley himself mentioned the flag in correspondence back home. He wrote: “In all my letter, I forgot to tell you under what banner we fought so bravely. It was that glorious emblem of native rights, that being the banner which should have floated over our native soil many years ago, it was St. Patrick, the Harp of Erin, the Shamrock upon a green field.” Another account stated that the flag displayed an Irish harp along with the Mexican coat of arms. Underneath the Arms of Mexico there was a scroll reading, “Freedom for the Mexican Republic.” Underneath the harp was the motto in Gaelic “Erin go Brágh,” Ireland forever. On the other side of the flag Saint Patrick was depicted holding a pastoral staff and standing on a serpent. The Patricios may have used different flags for their infantry and artillery units, and another flag may have been used after they were reorganized in the later days of the Mexican War.

The first major military engagement of the San Patricios occurred during the Battle of Monterrey on September 21, 1846. As part of the Mexican Army of the North, the Saint Patrick’s Battalion fought against what would later be called the American Army of Occupation comprised of United States Regulars, volunteers and Texas Rangers under the command of General Zachary Taylor. Although the Patricios pushed back the Americans three times, driving them out of the heart of the city of Monterrey, ultimately the Mexican commanders decided to retreat and abandon the city. The Mexicans regrouped and gathered more forces, later to be joined by hundreds of soldiers out of Mexico City under the command of Antonio López de Santa Anna.

The Irish battalion’s next major engagement was at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican state of Coahuila on February 23, 1847. In intense fighting throughout the day the San Patricios would lose a full one third of their members. The Mexicans lost the battle and retreated to San Luis Potosí. In his battle report for Buena Vista, General Francisco Mejia described the battalion’s conduct as “worthy of the most consummate praise because the men fought with daring bravery.” Several of the Patricios were awarded the War Cross by the government of Mexico and after the battle many were given promotions in rank.

A few weeks after the Mexican defeat at the Battle of Monterrey the focus of the war shifted from the northern frontier areas to the Mexican Gulf Coast. General Winfield Scott landed in Veracruz with 9,000 US troops so the Saint Patrick’s Battalion was sent to the town of Jalapa in the state of Veracruz. Although part of the 8,700-man Mexican force, the Patricios along with the rest of the forces under the command of Santa Anna were outflanked by General Scott and wound up losing the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847. The Mexicans suffered 1,000 casualties to the Americans’ mere 63 and over 3,000 Mexican soldiers were captured. Among them were members of the Patricios.

In June of 1847 General Santa Anna reorganized parts of the Mexican army and created a foreign legion. The Saint Patrick’s Battalion was transferred from the artillery branch to the infantry and merged into this newly formed Mexican Foreign Legion. The Patricios then became known as the First and Second Militia Infantry Companies of Saint Patrick. Colonel Francisco Moreno was made commander, with Captain John Riley in charge of the First Company and Captain Santiago O’Leary of the Second Company. The companies were more commonly referred to as “The Foreign Legion of Saint Patrick.”

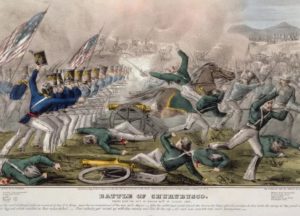

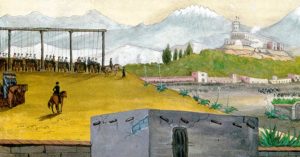

Four months after the Battle of Cerro Gordo, the Patricios made their last stand at the Battle of Churubusco just outside of Mexico City. Churubusco was the site of a thick-walled monastery that was built by the Spanish atop the ruins of an Aztec temple dedicated to the Mesoamerican war god Huitzilopochtli. Again, the Patricios fought gallantly and fiercely, but they ultimately lost, and so did Mexico. After the battle, 85 Patricios were captured by the Americans and 72 were tried as US Army deserters in a series of courts-martial. During these trials there were no lawyers present, no defenses given, and no transcripts were made at the proceedings. Those not convicted of desertion during war time were given 50 lashes and subject to hot iron brands to the face in the form of the letter “D” for “deserter.” John Riley suffered this fate as he deserted the US Army before the Mexican War began. Those who deserted after the war started suffered the ultimate fate. 50 members of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion were officially executed by the US Army by hanging, which was the largest mass execution in the history of the United States. The hangings took place on three days and in three different places. 16 were executed on September 10, 1847 at San Ángel, the site of Mexican President Zedillo’s speech 150 years later. The town of Mixoac was the site of 4 executions the following day. By order of General Winfield Scott, the remaining 30 were executed in full view of Chapultepec Castle. While on the gallows waiting to be hanged, the Patricios witnessed the final moments of the Battle of Chapultepec Hill. According to General Scott’s wishes, at the precise

Four months after the Battle of Cerro Gordo, the Patricios made their last stand at the Battle of Churubusco just outside of Mexico City. Churubusco was the site of a thick-walled monastery that was built by the Spanish atop the ruins of an Aztec temple dedicated to the Mesoamerican war god Huitzilopochtli. Again, the Patricios fought gallantly and fiercely, but they ultimately lost, and so did Mexico. After the battle, 85 Patricios were captured by the Americans and 72 were tried as US Army deserters in a series of courts-martial. During these trials there were no lawyers present, no defenses given, and no transcripts were made at the proceedings. Those not convicted of desertion during war time were given 50 lashes and subject to hot iron brands to the face in the form of the letter “D” for “deserter.” John Riley suffered this fate as he deserted the US Army before the Mexican War began. Those who deserted after the war started suffered the ultimate fate. 50 members of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion were officially executed by the US Army by hanging, which was the largest mass execution in the history of the United States. The hangings took place on three days and in three different places. 16 were executed on September 10, 1847 at San Ángel, the site of Mexican President Zedillo’s speech 150 years later. The town of Mixoac was the site of 4 executions the following day. By order of General Winfield Scott, the remaining 30 were executed in full view of Chapultepec Castle. While on the gallows waiting to be hanged, the Patricios witnessed the final moments of the Battle of Chapultepec Hill. According to General Scott’s wishes, at the precise  moment that the American flag was hoisted over the castle, the men were executed, including Francis O’Connor who had had both legs amputated the day before. The cruel and sadistic nature of this spectacle made newspaper headlines around the world. In an official statement, the Mexican government described the hangings as “a cruel death of horrible torments, improper in a civilized age, and ironic for a people who aspire to the title of illustrious and humane.” The execution of the Patricios would haunt General Winfield Scott 5 years later when it was brought up during his run for the American Presidency in 1852. Historians believe that the executions cost him the Irish vote and he fell out of favor with others who were sympathetic to what happened that day at Chapultepec.

moment that the American flag was hoisted over the castle, the men were executed, including Francis O’Connor who had had both legs amputated the day before. The cruel and sadistic nature of this spectacle made newspaper headlines around the world. In an official statement, the Mexican government described the hangings as “a cruel death of horrible torments, improper in a civilized age, and ironic for a people who aspire to the title of illustrious and humane.” The execution of the Patricios would haunt General Winfield Scott 5 years later when it was brought up during his run for the American Presidency in 1852. Historians believe that the executions cost him the Irish vote and he fell out of favor with others who were sympathetic to what happened that day at Chapultepec.

Many members of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion escaped capture. After the war ended the unit dissolved and its members went their separate ways. Some returned to Ireland or to other parts of Europe, but many decided to stay to make a go of it in the land they fought for. Mexico made good on its land grant promises and some former Patricios became farmers or hacienda owners, married, raised families and contributed to the patchwork quilt of mestizaje that is Mexico. There are no records of any Patricios returning to the United States. Although not well known in the US the men of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion are honored as beloved heroes by the countries of Mexico and Ireland. In the birthplace of John Riley, the town of Clifden, every September 12th they proudly fly the Mexican flag. The bravery and sacrifice of the San Patricios will never be forgotten.

REFERENCES

Fogarty, James. “The St. Patricio Battalion: The Irish Soldiers of Mexico,” In, Society for Irish Latin American Studies, September 2005.

Miller, Robert Ryal. Shamrock and Sword, The Saint Patrick’s Battalion in the US—Mexican War. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989. We are Amazon affiliates. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3bLoaKL