Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

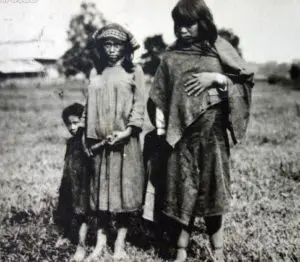

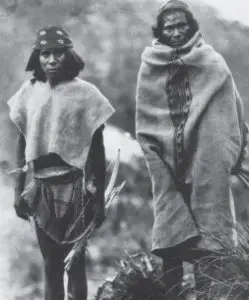

How many years have the Tarahumara people have lived in what is now the Mexican state of Chihuahua? No one knows for sure. When the Spanish arrived in the late 1500s to the southern part of their homeland, the Tarahumara lived in small farming villages in the mountains and the lowlands. Some researchers believe these people migrated south as refugees from the collapsing Mogollon Culture which flourished from about 200 AD to around 1400 AD in what is now the northern part of the Mexican state of Chihuahua and the southern parts of the US states of Arizona and New Mexico. When the Spanish encountered the Tarahumara, these people told the Europeans that they called themselves the Rarámuri. Today the word Rarámuri is used by indigenous purists and by a newly sensitive Mexican government to describe the Tarahumara, although in the Tarahumara language the name rarámuri literally means “men.” In their language the word “woman” is mukí and “women” are called omugí or igómale. So those wishing to be more inclusive and “decolonizing” and use the term Rarámuri are only describing half the population of these people. As is standard throughout Mexico Unexplained, the commonly known term to English-speakers is used, and in this case that would be a simple “Tarahumara.”

How many years have the Tarahumara people have lived in what is now the Mexican state of Chihuahua? No one knows for sure. When the Spanish arrived in the late 1500s to the southern part of their homeland, the Tarahumara lived in small farming villages in the mountains and the lowlands. Some researchers believe these people migrated south as refugees from the collapsing Mogollon Culture which flourished from about 200 AD to around 1400 AD in what is now the northern part of the Mexican state of Chihuahua and the southern parts of the US states of Arizona and New Mexico. When the Spanish encountered the Tarahumara, these people told the Europeans that they called themselves the Rarámuri. Today the word Rarámuri is used by indigenous purists and by a newly sensitive Mexican government to describe the Tarahumara, although in the Tarahumara language the name rarámuri literally means “men.” In their language the word “woman” is mukí and “women” are called omugí or igómale. So those wishing to be more inclusive and “decolonizing” and use the term Rarámuri are only describing half the population of these people. As is standard throughout Mexico Unexplained, the commonly known term to English-speakers is used, and in this case that would be a simple “Tarahumara.”

The Tarahumara first made contact with the Spanish sometime in the late 1500s. Probably some unknown explorer or fortune-hunter came upon a peaceful Tarahumara village somewhere in southern Chihuahua. The missionaries arrived in Tarahumara territory along with Spanish miners in the early 1600s. The first formal mission called San Pablo was founded by a Jesuit named Juan Fontes in 1607 near the modern town of Mariano Balleza, Chihuahua near the state border with Durango. The mission was abandoned 9 years later in the year 1616 after it suffered severe attacks from the Tepehuan people. By the year 1640 the Jesuits were back with military support and founded several missions in what is now southern Chihuahua. Initially, the Tarahumara were either indifferent or somewhat welcoming to the newcomers. Some researchers believe that they were either seeking the food and shelter the missions offered and possibly wanted protection from the Chichimeca and other warlike neighbors. Some believe that those Tarahumara who entered the mission system willfully did so to escape slave-raiding Spaniards who would come to their villages and steal people to work in the mines. Some anthropologists also believe that the  Tarahumara who willfully went to the missions were ready for something new as they saw their old world and belief systems crumble around them. From the early days, the Spanish, and soon the Tarahumara themselves, identified two types of Tarahumara, the bautizados, literally, “the baptized,” who had embraced the mission system and Christianity, ultimately; and the gentiles, those Tarahumara who chose to continue to live a traditional existence away from even the remotest contact with the Europeans. In 1648 a Tarahumara rebellion instigated by traditional mountain-dwelling Tarahumara sought to drive the Jesuits out of all Tarahumara lands. The last straw was the sacking and burning of the Mission of San Francisco de Borja located about 45 miles southwest of the modern state capital city of Chihuahua. The Jesuits returned to the area with a larger military contingent in the early 1670s and baptized thousands of Tarahumara over the course of a few short years. There were some skirmishes between the Spanish and Tarahumara between 1696 and 1698, but by 1700 most of Tarahumara territory had been evangelized and there were no more organized and open hostile acts. During this time there were still some Tarahumara who held on to their traditional beliefs in the mountains far away from the reach of the Spanish Empire.

Tarahumara who willfully went to the missions were ready for something new as they saw their old world and belief systems crumble around them. From the early days, the Spanish, and soon the Tarahumara themselves, identified two types of Tarahumara, the bautizados, literally, “the baptized,” who had embraced the mission system and Christianity, ultimately; and the gentiles, those Tarahumara who chose to continue to live a traditional existence away from even the remotest contact with the Europeans. In 1648 a Tarahumara rebellion instigated by traditional mountain-dwelling Tarahumara sought to drive the Jesuits out of all Tarahumara lands. The last straw was the sacking and burning of the Mission of San Francisco de Borja located about 45 miles southwest of the modern state capital city of Chihuahua. The Jesuits returned to the area with a larger military contingent in the early 1670s and baptized thousands of Tarahumara over the course of a few short years. There were some skirmishes between the Spanish and Tarahumara between 1696 and 1698, but by 1700 most of Tarahumara territory had been evangelized and there were no more organized and open hostile acts. During this time there were still some Tarahumara who held on to their traditional beliefs in the mountains far away from the reach of the Spanish Empire.

In 1767 a momentous event occurred that would shape the religious and spiritual life of the Tarahumara for centuries to come. The king of Spain expelled the Jesuit Order from all Spanish territories, including New Spain. While some missions in Tarahumara lands were turned over to the Franciscans and some secular Catholic priests took over some smaller parishes, the Jesuits left a hole in the spiritual life of the Tarahumara that was not easily filled. A rigid control over all aspects of religion was gone and some Tarahumara communities were left with no priest or anyone available to conduct Catholic rituals and administer the sacraments. There was still much of the traditional Tarahumara religion remaining, and in the period of time that strict Catholic control was lacking – some 130 years – the Tarahumara religion experienced a kind of syncretism, a unique blending of the old religion and the new. Although the Catholic Church and now Protestant denominations have long since reestablished themselves among the Tarahumara, there is still much in the modern belief system of these people that is a beautiful mix of different faiths.

In the Tarahumara religion there exists three prime supernatural forces. God the Father is called Riosi, which in pre-Hispanic times was Onoruame, or “The Great Father.” He is often associated with the sun. God has a wife called Lyeruame which is associated with the Virgin Mary and the moon. God and his wife live in Heaven with their male children called sukrito, which is a corruption of the Spanish word “Jesucristo.” Their female children are called the santi, which comes from the Latin word meaning, “saints.” The children of God and his wife are personified in the traditional saint iconography of the Catholic Church and are prayed to much like any good Catholic would to the Catholic saints. The Tarahumara counterpart to the Devil is called Riablo, but this entity is not exactly the same being as was introduced by the Spanish. In some stories the Riablo is God’s brother and in many instances, he works with God to dish out punishments to people on earth exhibiting bad behavior. Riablo can be kept at bay by offering small sacrifices to him. To the faithful, Riablo can be changed into an entity for good if he is appeased properly.

In the Tarahumara religion there exists three prime supernatural forces. God the Father is called Riosi, which in pre-Hispanic times was Onoruame, or “The Great Father.” He is often associated with the sun. God has a wife called Lyeruame which is associated with the Virgin Mary and the moon. God and his wife live in Heaven with their male children called sukrito, which is a corruption of the Spanish word “Jesucristo.” Their female children are called the santi, which comes from the Latin word meaning, “saints.” The children of God and his wife are personified in the traditional saint iconography of the Catholic Church and are prayed to much like any good Catholic would to the Catholic saints. The Tarahumara counterpart to the Devil is called Riablo, but this entity is not exactly the same being as was introduced by the Spanish. In some stories the Riablo is God’s brother and in many instances, he works with God to dish out punishments to people on earth exhibiting bad behavior. Riablo can be kept at bay by offering small sacrifices to him. To the faithful, Riablo can be changed into an entity for good if he is appeased properly.

In the beginning, according to the Tarahumara God and his wife lived in the sky as the sun and moon. They clothed themselves in palm fronds and very little light reached the earth save for the bright light of the Evening Star. The Evening Star was originally a louse that used to live in the sun’s head. When God’s wife noticed how brightly the Evening Star was shining, she ate it and thus plunged the earth into a period of semi-darkness. The people living on the earth built three tall crosses out of redwood, soaked them in the corn alcohol called batari and set them on fire. These three crosses are used in many modern-day Tarahumara ceremonies and are seen at the altars in many Tarahumara churches. The three blazing crosses burned away the palm leaves hiding the sun and moon. This so angered Riosi – God the Father – that he flooded the world, saving only one Tarahumara boy and one girl, and giving them three seeds of both corn and squash so they could grow their own food. The girl and boy created a family and grew much food, and the world became abundant again.

The batari alcohol poured on the crosses in the previous story caused much conflict between the Tarahumara and their Spanish overlords. A fermented drink made from sprouted corn, the Spanish called this intoxicating substance tesgüino. As batari only has a shelf life of 24 hours before it goes bad, once it is made, it must be consumed. The drink is associated with community religious festivals and with smaller ceremonies. One anthropologist noted that the Tarahumara may spend up to 100 days per year preparing and consuming batari. Villages often deal with the aftereffects of group batari consumption for days. It’s no wonder why the early church fathers saw batari as evil and tried to have it banned. They were utterly unsuccessful. The Tarahumara also use peyote in religious ceremonial activities, but it is not as widespread as batari. Any crimes or minor indiscretions committed by Tarahumara while under the influence of batari or peyote are immediately forgiven.

To connect with the spirit world the Tarahumara have two types of religious practitioners that still exist in the modern world: The oorúame and the sukurúame. Oorúame could loosely be translated as “shaman,” or someone who practices benevolent magic. Sukurúame means something like “sorcerer,” or someone who conducts rituals and ceremonies with evil intent. These are not specific roles or positions in Tarahumara society for religious practitioners. A man thought of as oorúame could fulfill the role of sukurúame and vice versa. The Tarahumara shamans are traditionally charged with leading public ceremonies but are also responsible for more private, one-on-one curing or healing rituals. So, in a sense, they are also village medicine men.

To connect with the spirit world the Tarahumara have two types of religious practitioners that still exist in the modern world: The oorúame and the sukurúame. Oorúame could loosely be translated as “shaman,” or someone who practices benevolent magic. Sukurúame means something like “sorcerer,” or someone who conducts rituals and ceremonies with evil intent. These are not specific roles or positions in Tarahumara society for religious practitioners. A man thought of as oorúame could fulfill the role of sukurúame and vice versa. The Tarahumara shamans are traditionally charged with leading public ceremonies but are also responsible for more private, one-on-one curing or healing rituals. So, in a sense, they are also village medicine men.

Song and dance are important parts of the civic and religious lives of the Tarahumara. In her article titled: “Religion and Ritual Among the Tarahumara of Northern Mexico,” author Olivia Arrieta has this to say about music and dancing among the Tarahumara:

“Dancing and chanting are part of every ritual, but are especially important in the traditional yumari and tutuburi. Yumari dancers are accompanied by flute and drum music and are under the direction of the oorúame. Tutuburi dances are performed in a special circular dance area in front of a native altar and led by a saweame chanting and using a ceremonial rattle. The male dancers in the Yumari move in a single line to the left of the saweame, a few steps from the altar. Female dancers including women and girls participate with males in the Tutuburi dance only, moving across the dance pavilion in the opposite direction of the males.”

Song and dance occur in abundance on the important Tarahumara feast days that correspond to the Catholic calendar: December 12th, the saint’s day for the Virgin of Guadalupe; Christmas Eve on December 24th; Three King’s Day or the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6th; and the semana santa or Holy Week proceeding Easter. Like many other indigenous groups of northern Mexico – including the Yaqui and the Mayó – Easter Week celebrations are the most important on the ritual calendar. During the semana santa, Tarahumara settlements invest much energy and resources into putting on elaborate pageants, parades and religious ceremonies. The chief themes of the Easter ceremonies center around community unification and ensuring agricultural abundance, with many aspects of these ceremonies dating well into pre-Hispanic times. Pleasing God and making sure every Tarahumara is included and accounted for are paramount. Like some of their indigenous neighbors, the Tarahumara do a deer dance during the Easter festivities. Older men paint their bodies in elaborate patterns, don headdresses of turkey feathers and wear deer hoof rattles around their waists, along with cocoon rattles on their feathered ankles. A traditional Catholic mass and procession always accompany these uniquely Tarahumara celebrations, and church officials, whether Protestant or Catholic rarely frown upon these festivities in modern times. Throughout history the Tarahumara have maintained a kind of happy medium with their spirituality, incorporating those symbols and practices of the Spanish colonizers that best fit their needs. The unique and beautiful way in which the Tarahumaras interact with their universe will surely continue for many years to come.

REFERENCES