Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

When I was a tour guide in Mexico almost 20 years ago, one of my tour participants happened to be the highest-ranking Freemason in his state. On Day 3, after the tour was over for the afternoon, I decided to take a walk around the neighborhood surrounding our hotel. Out on a walk also was this high-ranking Freemason and his wife. I joined up with them and within minutes we found ourselves in front of the Grand Lodge of Western Mexico located in downtown Guadalajara. My tour participant knocked on the door, showed identification, and the guy opening the door let all 3 of us in. I was not a Mason but was given free rein to explore the place. We eventually made it to the upper level to a room with a checkered floor whose entrance was guarded by two pillars topped with polished blue orbs that looked like globes. Lining the walls were rows of chairs. At the far end of the room there appeared to be an altar with burgundy-colored curtains behind it. To me, the setting made me think that a wizard with a pointy top hat would come out from behind the curtains at any moment. This room was some sort of inner sanctum that I knew I probably was not allowed to be in but was only there because of who I was with. This strange room was not the most curious part of the lodge for me. In the entrance of the lodge was a main room with busts of major political figures from Mexico’s history: Juarez, Father Hidalgo, Morelos and more. I was really interested in why Hidalgo was in this hallowed room of heroes because he was a Catholic priest, and I knew the Church was not so fond of the Masons. I voiced my wonder out loud. The wife of the high-ranking American Mason responded to me:

When I was a tour guide in Mexico almost 20 years ago, one of my tour participants happened to be the highest-ranking Freemason in his state. On Day 3, after the tour was over for the afternoon, I decided to take a walk around the neighborhood surrounding our hotel. Out on a walk also was this high-ranking Freemason and his wife. I joined up with them and within minutes we found ourselves in front of the Grand Lodge of Western Mexico located in downtown Guadalajara. My tour participant knocked on the door, showed identification, and the guy opening the door let all 3 of us in. I was not a Mason but was given free rein to explore the place. We eventually made it to the upper level to a room with a checkered floor whose entrance was guarded by two pillars topped with polished blue orbs that looked like globes. Lining the walls were rows of chairs. At the far end of the room there appeared to be an altar with burgundy-colored curtains behind it. To me, the setting made me think that a wizard with a pointy top hat would come out from behind the curtains at any moment. This room was some sort of inner sanctum that I knew I probably was not allowed to be in but was only there because of who I was with. This strange room was not the most curious part of the lodge for me. In the entrance of the lodge was a main room with busts of major political figures from Mexico’s history: Juarez, Father Hidalgo, Morelos and more. I was really interested in why Hidalgo was in this hallowed room of heroes because he was a Catholic priest, and I knew the Church was not so fond of the Masons. I voiced my wonder out loud. The wife of the high-ranking American Mason responded to me:

“They were all masons. This country was founded by them. Father Hidalgo was secretly a mason even though the church was against the whole movement. The masons were all about creating new power structures and in Mexico they were all about breaking away from Spain.”

I found this all rather interesting and vowed one day to look into this further. And now here we have Mexico Unexplained Episode number 409.

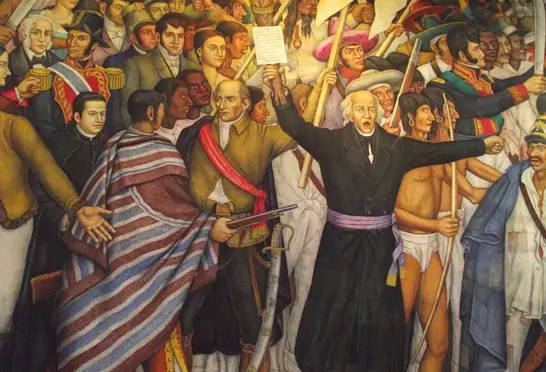

The story of Mexico’s independence from Spain, culminating in 1821, is often told as a tale of heroic priests, oppressed masses, and a crumbling colonial empire. Figures like Miguel Hidalgo, with his fiery Cry of Dolores in 1810, and Agustín de Iturbide, who sealed the deal with the Plan of Iguala, dominate the narrative. Yet beneath this surface lies a shadowy thread that some historians and enthusiasts whisper about: the influence of secret societies such as Freemasonry. Could this mysterious fraternal order, with its Enlightenment ideals and clandestine networks, have played a pivotal role in sparking and shaping Mexico’s break from Spain in the late 1700s and early 1800s? We will delve into the evidence, the speculation, and the historical context to uncover whether Freemasons were hidden architects of Mexican independence.

The story of Mexico’s independence from Spain, culminating in 1821, is often told as a tale of heroic priests, oppressed masses, and a crumbling colonial empire. Figures like Miguel Hidalgo, with his fiery Cry of Dolores in 1810, and Agustín de Iturbide, who sealed the deal with the Plan of Iguala, dominate the narrative. Yet beneath this surface lies a shadowy thread that some historians and enthusiasts whisper about: the influence of secret societies such as Freemasonry. Could this mysterious fraternal order, with its Enlightenment ideals and clandestine networks, have played a pivotal role in sparking and shaping Mexico’s break from Spain in the late 1700s and early 1800s? We will delve into the evidence, the speculation, and the historical context to uncover whether Freemasons were hidden architects of Mexican independence.

To understand Freemasonry’s potential role in Mexico, we must first step back to its broader context in the 18th century. Freemasonry emerged in Europe as a fraternal organization blending medieval guild traditions with Enlightenment philosophy. By the late 1700s, it had evolved into a network of lodges promoting ideals of liberty, equality, and reason—ideas that often clashed with the absolutist monarchies and rigid religious hierarchies of the time. In Spain, Freemasonry took root under the Bourbon dynasty, particularly during the reign of Charles the Third who ruled from 1759 to 1788. Charles was a monarch known for his reformist yet authoritarian streak. In 1767, a Grand Lodge of Spain was established, led by the Count of Aranda, Charles the Third’s prime minister, and included many prominent nobles and officials. This was no mere social club; it was a space where Enlightenment ideas fermented, often in opposition to the Catholic Church’s dominance.

Spain’s colonial empire, including New Spain, was not immune to these currents. The Bourbon Reforms of the 18th century aimed to centralize control and extract more wealth from the colonies, alienating the creole elite, the American-born Spaniards who chafed under the privileges of the peninsulares who were the Spain-born subjects of New Spain. At the same time, the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish territories in 1767, ordered by Charles the Third, stirred resentment among colonists who saw the Jesuits as cultural and intellectual allies. This act, perceived as an attack on local autonomy, created fertile ground for subversive ideas. Freemasonry, with its emphasis on rational governance and individual rights, offered a framework for dissent—one that could operate in secret, beyond the reach of colonial authorities and the Inquisition.

Spain’s colonial empire, including New Spain, was not immune to these currents. The Bourbon Reforms of the 18th century aimed to centralize control and extract more wealth from the colonies, alienating the creole elite, the American-born Spaniards who chafed under the privileges of the peninsulares who were the Spain-born subjects of New Spain. At the same time, the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish territories in 1767, ordered by Charles the Third, stirred resentment among colonists who saw the Jesuits as cultural and intellectual allies. This act, perceived as an attack on local autonomy, created fertile ground for subversive ideas. Freemasonry, with its emphasis on rational governance and individual rights, offered a framework for dissent—one that could operate in secret, beyond the reach of colonial authorities and the Inquisition.

Evidence of Freemasonry in colonial Mexico during the late 18th century is sparse and often circumstantial, largely because the Spanish Crown and the Catholic Church viewed it with deep suspicion. The Inquisition, still active in Mexico, branded Freemasonry as heretical and seditious, forcing any lodges to operate clandestinely. Yet the ideas of the Enlightenment, carried by books, travelers, and returning students, seeped into the colony. The Creoles, educated and ambitious, were particularly receptive. They resented their second-class status and saw in Freemasonry a vision of a society where merit, not birth, determined power.

Speculation about early Masonic activity in Mexico often points to the port cities of Veracruz and Campeche, gateways for foreign influence. In 1816, the York Rite Grand Lodge of Louisiana reportedly chartered a lodge called Amigos Reunidos Number 8 in Veracruz, followed by Reunida La Virtud Number 9 in Campeche in 1817. These lodges, if they existed, leave little trace in official records, suggesting they either dissolved quickly or operated in utmost secrecy. However, their timing—on the eve of Mexico’s independence struggle—raises intriguing questions. Were these outposts of American Freemasonry planting seeds of rebellion in a colony already simmering with discontent?

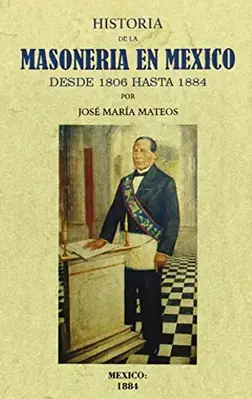

More tantalizing is the claim by José María Mateos, a 19th-century Mexican liberal politician, who in 1884 asserted that key independence leaders like Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, and Ignacio Allende were Freemasons. Mateos suggested they were initiated in a lodge called “Moral Architecture” – later known as Bolívar Number 73 – though he offered no documentary proof. Historians have debated this claim fiercely. Hidalgo, a Catholic priest, seems an unlikely candidate given the Church’s hostility to Freemasonry, yet his progressive ideas—abolishing slavery, redistributing land—echo outwardly professed Masonic principles of equality and justice. Morelos, another priest-turned-revolutionary, drafted the Sentimientos de la Nación in 1813, a document that blends republicanism with social reform, hinting at Enlightenment influences that could align with Masonic thought.

More tantalizing is the claim by José María Mateos, a 19th-century Mexican liberal politician, who in 1884 asserted that key independence leaders like Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, and Ignacio Allende were Freemasons. Mateos suggested they were initiated in a lodge called “Moral Architecture” – later known as Bolívar Number 73 – though he offered no documentary proof. Historians have debated this claim fiercely. Hidalgo, a Catholic priest, seems an unlikely candidate given the Church’s hostility to Freemasonry, yet his progressive ideas—abolishing slavery, redistributing land—echo outwardly professed Masonic principles of equality and justice. Morelos, another priest-turned-revolutionary, drafted the Sentimientos de la Nación in 1813, a document that blends republicanism with social reform, hinting at Enlightenment influences that could align with Masonic thought.

The turning point for Mexican independence came in 1808, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain, deposed King Ferdinand the Seventh, and installed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the throne. This crisis fractured Spanish authority, leaving New Spain in a power vacuum. Creoles initially sought autonomy within the empire, but when their hopes were dashed by the hardline Spain-born loyalists, rebellion became the only path. This moment of chaos was a golden opportunity for secret societies like Freemasonry to mobilize.

In Spain, the Napoleonic upheaval galvanized Freemasons, many of whom supported the liberal Constitution of 1812, enacted by the Cádiz Cortes. This document promised greater representation for the colonies, but its implementation faltered, further alienating the Creole class. In Mexico, the turmoil emboldened conspiracies, such as the 1808 plot led by Creole elites in Mexico City, which was swiftly crushed by colonial authorities. While no direct evidence ties this plot to Freemasonry, the participants’ demands for self-governance mirror Masonic ideals. The secrecy of such groups would have been a natural shield against the Inquisition’s prying eyes.

Hidalgo’s Cry of Dolores in 1810 marked the eruption of open revolt, but the movement’s intellectual roots may stretch back to these earlier, hidden networks. The priest’s call to arms was not just a spontaneous outburst; it built on years of Creole frustration and Enlightenment-inspired agitation. If Hidalgo was indeed a Mason, as Mateos claimed, his lodge could have been a crucible for planning and radicalization. Yet without records—likely destroyed or never kept due to the risks—the connection remains speculative.

The independence movement’s decisive phase came in 1821, when Agustín de Iturbide, a royalist general, switched sides and allied with insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero. Their Plan of Iguala promised independence, Catholicism, and equality between native-born and European-born Spaniards—three guarantees that won broad support. On August 24, 1821, the Treaty of Córdoba formalized Mexico’s break from Spain, and Iturbide soon crowned himself emperor. Intriguingly, there is stronger evidence of Iturbide’s Masonic ties. Documents suggest he was a member, possibly initiated during his military career, and his pragmatic, conservative vision of independence aligns with the York Rite Masonry that later dominated Mexico.

The Dominican friar Servando Teresa de Mier, the subject of Mexico Unexplained episode number 180, https://mexicounexplained.com/the-unpriestly-life-of-father-servando-teresa-de-mier/ who was another key figure in the independence struggle, is also widely accepted as a Freemason. A radical thinker exiled multiple times by Spanish authorities, Mier’s writings championed Mexican identity and sovereignty, often with a flair for Masonic symbolism. His influence on Iturbide and the broader movement underscores how Masonic networks could bridge ideological divides—uniting Mexican-born elites, military officers, and intellectuals in a common cause.

The Dominican friar Servando Teresa de Mier, the subject of Mexico Unexplained episode number 180, https://mexicounexplained.com/the-unpriestly-life-of-father-servando-teresa-de-mier/ who was another key figure in the independence struggle, is also widely accepted as a Freemason. A radical thinker exiled multiple times by Spanish authorities, Mier’s writings championed Mexican identity and sovereignty, often with a flair for Masonic symbolism. His influence on Iturbide and the broader movement underscores how Masonic networks could bridge ideological divides—uniting Mexican-born elites, military officers, and intellectuals in a common cause.

After independence, Freemasonry emerged from the shadows. Lodges multiplied, splitting into rival factions: the York Rite, favored by conservatives like Iturbide, and the Scottish Rite, embraced by liberals. This division shaped Mexico’s turbulent post-independence politics, suggesting that Masonic influence didn’t end with the Treaty of Córdoba but evolved into a new battleground.

So, how much of this Masonic narrative holds water? The hard evidence is thin. No lodge records definitively place Hidalgo, Morelos, or Allende in Masonic ranks before 1810. The Inquisition’s vigilance and the chaos of war likely erased any paper trail. Mateos’s claims, made decades later, could be retrospective mythmaking by a liberal eager to tie Mexico’s heroes to a prestigious global movement. Yet the circumstantial case is compelling. The timing of Masonic expansion in Spain and the Americas, the overlap of Enlightenment ideals with revolutionary rhetoric, and the documented Masonic affiliations of figures like Iturbide and Mier suggest a plausible influence.

Critics argue that Freemasonry’s role has been exaggerated. The Mexican independence movement was a broad coalition—peasants, priests, Creoles, and mestizos—driven by local grievances like taxation, racial inequality, and food shortages, not abstract lodge rituals. Hidalgo’s rebellion, for instance, spiraled into a populist uprising far beyond any elite conspiracy. Yet this doesn’t preclude a Masonic spark. Secret societies often act as catalysts, planting ideas that ignite larger flames. The American Revolution, with its well-documented Masonic ties – think George Washington and Benjamin Franklin – offers a parallel: a small cadre of lodge brothers shaped a movement that outgrew them.

If Freemasonry did help birth Mexican independence, its legacy is bittersweet. The new nation stumbled into instability, with Iturbide’s empire collapsing by 1823 and decades of coups and foreign interventions following. The York-Scottish Rite rivalry fueled political chaos, notably in the career of Antonio López de Santa Anna, a confirmed Scottish Rite Mason whose life was reportedly spared at San Jacinto in 1836 by Masonic signals—a story as dramatic as it is unproven. By the late 19th century, Freemasonry’s influence waned as Mexico grappled with modernization and revolution.

The Freemasonic angle offers a tantalizing mystery: a secret society whispering in the shadows of a nation’s birth. It’s not the whole story—Hidalgo’s faith, the ambition of native-born elites, and the people’s rage were just as vital—but it adds a layer of intrigue. Picture clandestine meetings in Veracruz, coded messages passed under the Inquisition’s nose, and a priest like Hidalgo torn between his cassock and a Masonic apron. Whether fact or folklore, it’s a thread that invites us to question the official tale and peer into the hidden corners of history. Over two centuries later, the question lingers: how much of Mexico’s freedom was forged in the lodges of the Enlightenment? The evidence may never fully surface, but the speculation alone keeps the story alive, a perfect enigma to keep us all in a state of wonder.

The Freemasonic angle offers a tantalizing mystery: a secret society whispering in the shadows of a nation’s birth. It’s not the whole story—Hidalgo’s faith, the ambition of native-born elites, and the people’s rage were just as vital—but it adds a layer of intrigue. Picture clandestine meetings in Veracruz, coded messages passed under the Inquisition’s nose, and a priest like Hidalgo torn between his cassock and a Masonic apron. Whether fact or folklore, it’s a thread that invites us to question the official tale and peer into the hidden corners of history. Over two centuries later, the question lingers: how much of Mexico’s freedom was forged in the lodges of the Enlightenment? The evidence may never fully surface, but the speculation alone keeps the story alive, a perfect enigma to keep us all in a state of wonder.

REFERENCES

Greenleaf, Richard E. “Is Freemasonry’s Role in Mexican History a Secret in Plain Sight?” Mexico News Daily, June 8, 2022.