Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

The date was November 11, 791 AD. The place was the Maya city of Ak’e also known as Usiij Witz, which translates to “Vulture Hill,” in English. The ruler of this influential place, a strong middle-aged man named Chaan-muan, gathered together well-dressed nobles from his client cities and other allied city-states to dedicate a grand building. The building stood on top of a t-shaped platform and measured sixteen meters long, four meters deep, and seven meters tall. This new building contained three rooms and during the dedication ceremony the doorways of the rooms were covered by ceremonial curtains. With great pomp and ceremony, lord Chaan-muan gave the word for the removal of the curtains so that his guests could see what was inside the rooms. Undoubtedly, the nobles present gasped at what they saw. The morning light fell on magnificent paintings with sparkling blues and vibrant reds, frescoes so intricate their caliber had never been seen before in the Maya world. At the dedication ceremony, alongside the king of Usiij Witz was his first wife, a beautiful princess named Lady Rabbit from the more powerful and wealthier Pa’Chan Kingdom to the north. Pa’Chan, which loosely translates into English as, “Broken Sky,” or “Sky Torn Apart,” had had an uneasy relationship with Usiij Witz for many centuries, sometimes an ally and sometimes subjugating it. The ebb and flow of peace and war seemed to be at an ebb on that November day. Their wonder aside, the nobles present contemplated the paintings which cemented in their minds the hierarchy of power. With their three sons attending the building dedication, Chaan-muan and Lady Rabbit felt their family had a secure future as rulers of this realm. Their reign had been marked by great prosperity and increasing abundance. To all present, this golden age would last forever. No one at the ceremony could have predicted that in a span of a few more decades, less than two generations, the jungle would start to reclaim the city as the Classic Maya civilization would face complete and utter collapse.

The date was November 11, 791 AD. The place was the Maya city of Ak’e also known as Usiij Witz, which translates to “Vulture Hill,” in English. The ruler of this influential place, a strong middle-aged man named Chaan-muan, gathered together well-dressed nobles from his client cities and other allied city-states to dedicate a grand building. The building stood on top of a t-shaped platform and measured sixteen meters long, four meters deep, and seven meters tall. This new building contained three rooms and during the dedication ceremony the doorways of the rooms were covered by ceremonial curtains. With great pomp and ceremony, lord Chaan-muan gave the word for the removal of the curtains so that his guests could see what was inside the rooms. Undoubtedly, the nobles present gasped at what they saw. The morning light fell on magnificent paintings with sparkling blues and vibrant reds, frescoes so intricate their caliber had never been seen before in the Maya world. At the dedication ceremony, alongside the king of Usiij Witz was his first wife, a beautiful princess named Lady Rabbit from the more powerful and wealthier Pa’Chan Kingdom to the north. Pa’Chan, which loosely translates into English as, “Broken Sky,” or “Sky Torn Apart,” had had an uneasy relationship with Usiij Witz for many centuries, sometimes an ally and sometimes subjugating it. The ebb and flow of peace and war seemed to be at an ebb on that November day. Their wonder aside, the nobles present contemplated the paintings which cemented in their minds the hierarchy of power. With their three sons attending the building dedication, Chaan-muan and Lady Rabbit felt their family had a secure future as rulers of this realm. Their reign had been marked by great prosperity and increasing abundance. To all present, this golden age would last forever. No one at the ceremony could have predicted that in a span of a few more decades, less than two generations, the jungle would start to reclaim the city as the Classic Maya civilization would face complete and utter collapse.

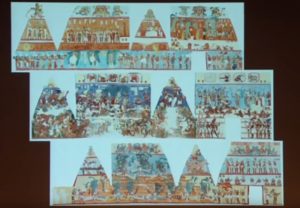

One thousand one hundred fifty-five years later, in the year 1946, American adventurer and photographer Giles Healey became the first non-Maya to see these magnificent murals, led to the site by a local Lancandon Maya whose people had been going to the ruins to pray for generations. Instead of Ak’e or Usiij Witz, the local people called the lost city Bonampak. Its larger and wealthier neighbor to the north, the original home of Bonampak’s beautiful foreign princess and the capital of the Kingdom of the Sky Torn Apart, was known as Yaxchilán. The names Bonampak and Yaxchilán are still in use today and are considered major archaeological sites in the modern Mexican state of Chiapas. Giles Healey marveled at what he saw in what would later be known as the Temple of the Murals: Floor to ceiling paintings across three rooms depicting lively scenes done in a refined style. He had rediscovered some of the best examples of ancient panting in the New World, a veritable Sistine Chapel of the ancient Maya. Like the Sistine Chapel, the paintings covering the walls were done in a fresco style. The paint was not applied directly to the wall but to a wet plaster spread on the surface of the wall. Although well over 11 centuries old, calcification from water seepage into the monument had preserved much of the colors and intricate details of the scenes on the walls. Healey noticed the blues in the painting sparkled when exposed to direct light, the paints having been mixed with azurite imported from copper mines in what is now the southern part of the American state of Arizona. The magnificent works took great skill, care and expense. After years of searching the tropical jungles of Mexico and Central America, Giles Healey had made his “great discovery.” He immediately took photographs and because of the poor lighting inside the building, Healey also hired local artists to create reproductions of the murals on the spot. It’s a good thing he did this. When Healey first entered the Temple of the Murals the surfaces of walls were damp from the centuries of water seeping into the structure. With the protective jungle cleared away from the Bonampak ruins, the paintings became vulnerable to the heat and subject to the dryness of the tropical dry season. The calcified surfaces began to dry out, turn white and deteriorate. In the 1950s, the copyists hired to painstakingly reproduce the murals had an idea to keep the paintings moist and to cut through the calcification. They applied kerosene to the walls. While some of them smoked while working, it was no wonder the greatest examples of ancient painting in the Americas did not meet their end in a massive blaze. By 1960, Mexican archaeologists took over control of Bonampak and began their own restoration of the murals under the direction of art historian and archaeologist Manuel de Castillo Negrete. Instead of using kerosene to moisten and clean the paintings, they used water. Unfortunately, the water came from a local swamp and as a result, living organisms from the swamp began to grow on the walls. By the early 1980s a team of Mexican and international art restorers began a comprehensive cleaning and restoration of the murals. Although the thorough cleaning brought back some of the vibrant colors and lively images, there was some loss. Using the restored walls, Giles Healey’s early photographs and drawings of the first copyists, a team led by Professor Mary Miller of Yale University has put together the most detailed and descriptive reproduction of the Bonampak murals in her work titled The Bonampak Documentation Project.

One thousand one hundred fifty-five years later, in the year 1946, American adventurer and photographer Giles Healey became the first non-Maya to see these magnificent murals, led to the site by a local Lancandon Maya whose people had been going to the ruins to pray for generations. Instead of Ak’e or Usiij Witz, the local people called the lost city Bonampak. Its larger and wealthier neighbor to the north, the original home of Bonampak’s beautiful foreign princess and the capital of the Kingdom of the Sky Torn Apart, was known as Yaxchilán. The names Bonampak and Yaxchilán are still in use today and are considered major archaeological sites in the modern Mexican state of Chiapas. Giles Healey marveled at what he saw in what would later be known as the Temple of the Murals: Floor to ceiling paintings across three rooms depicting lively scenes done in a refined style. He had rediscovered some of the best examples of ancient panting in the New World, a veritable Sistine Chapel of the ancient Maya. Like the Sistine Chapel, the paintings covering the walls were done in a fresco style. The paint was not applied directly to the wall but to a wet plaster spread on the surface of the wall. Although well over 11 centuries old, calcification from water seepage into the monument had preserved much of the colors and intricate details of the scenes on the walls. Healey noticed the blues in the painting sparkled when exposed to direct light, the paints having been mixed with azurite imported from copper mines in what is now the southern part of the American state of Arizona. The magnificent works took great skill, care and expense. After years of searching the tropical jungles of Mexico and Central America, Giles Healey had made his “great discovery.” He immediately took photographs and because of the poor lighting inside the building, Healey also hired local artists to create reproductions of the murals on the spot. It’s a good thing he did this. When Healey first entered the Temple of the Murals the surfaces of walls were damp from the centuries of water seeping into the structure. With the protective jungle cleared away from the Bonampak ruins, the paintings became vulnerable to the heat and subject to the dryness of the tropical dry season. The calcified surfaces began to dry out, turn white and deteriorate. In the 1950s, the copyists hired to painstakingly reproduce the murals had an idea to keep the paintings moist and to cut through the calcification. They applied kerosene to the walls. While some of them smoked while working, it was no wonder the greatest examples of ancient painting in the Americas did not meet their end in a massive blaze. By 1960, Mexican archaeologists took over control of Bonampak and began their own restoration of the murals under the direction of art historian and archaeologist Manuel de Castillo Negrete. Instead of using kerosene to moisten and clean the paintings, they used water. Unfortunately, the water came from a local swamp and as a result, living organisms from the swamp began to grow on the walls. By the early 1980s a team of Mexican and international art restorers began a comprehensive cleaning and restoration of the murals. Although the thorough cleaning brought back some of the vibrant colors and lively images, there was some loss. Using the restored walls, Giles Healey’s early photographs and drawings of the first copyists, a team led by Professor Mary Miller of Yale University has put together the most detailed and descriptive reproduction of the Bonampak murals in her work titled The Bonampak Documentation Project.

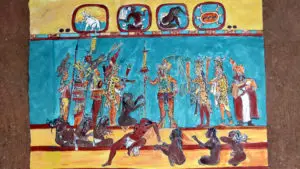

So, what do we see in the murals? As mentioned previously, the murals exist in three separate rooms but are part of a flowing narrative depicting actual events. According to most scholars, Room Number One shows the line of succession and King Chaan-muan establishing his son’s right to rule. The panels show many dignitaries dressed in elaborate regalia while musicians fill the room with the music of celebration. Among the dignitaries are the 8 sajals, or the regional governors of Bonampak’s territories. The musicians blow trumpets, bang drums, and shake rattles and filled turtle shells. The central figure attending to the nobles is the king and below him are three dancing young men, identified as his sons: Chooj, Bird Balam and Aj Balam. Chooj is in the center and is King Chaan-muan’s heir. It is unknown historically whether he assumed the throne. Three curiosities exist in Room One worth noting. There is a scene of a lone figure presenting a baby to the nobility. At first researchers thought this baby was the representation of King Chaan-muan’s heir, but then someone noticed the baby has a painted face and is wearing specific clothing, indicating that the baby is a girl. No one is looking at the baby, as if no one is interested in her. Could she be a future queen or a mother of a ruler? Perhaps she was a daughter of the king and Lady Rabbit who passed away before adulthood? A second curious thing in Room One is the use of quotation marks in one of the murals. That is the only example of quotes in pre-Columbian art. It is as if the viewer is supposed to recite what is written in the frescoes upon seeing the scene. The last curious element of the paintings is what archaeologists call Human Figure Number 71, a man holding a long cigarette in his mouth. He stands the way bored smokers stand today, with slightly hunched posture as if leaning, with one arm holding the cigarette and the other arm draped lazily across his torso. His expression is one of calm, boredom or disinterest.

So, what do we see in the murals? As mentioned previously, the murals exist in three separate rooms but are part of a flowing narrative depicting actual events. According to most scholars, Room Number One shows the line of succession and King Chaan-muan establishing his son’s right to rule. The panels show many dignitaries dressed in elaborate regalia while musicians fill the room with the music of celebration. Among the dignitaries are the 8 sajals, or the regional governors of Bonampak’s territories. The musicians blow trumpets, bang drums, and shake rattles and filled turtle shells. The central figure attending to the nobles is the king and below him are three dancing young men, identified as his sons: Chooj, Bird Balam and Aj Balam. Chooj is in the center and is King Chaan-muan’s heir. It is unknown historically whether he assumed the throne. Three curiosities exist in Room One worth noting. There is a scene of a lone figure presenting a baby to the nobility. At first researchers thought this baby was the representation of King Chaan-muan’s heir, but then someone noticed the baby has a painted face and is wearing specific clothing, indicating that the baby is a girl. No one is looking at the baby, as if no one is interested in her. Could she be a future queen or a mother of a ruler? Perhaps she was a daughter of the king and Lady Rabbit who passed away before adulthood? A second curious thing in Room One is the use of quotation marks in one of the murals. That is the only example of quotes in pre-Columbian art. It is as if the viewer is supposed to recite what is written in the frescoes upon seeing the scene. The last curious element of the paintings is what archaeologists call Human Figure Number 71, a man holding a long cigarette in his mouth. He stands the way bored smokers stand today, with slightly hunched posture as if leaning, with one arm holding the cigarette and the other arm draped lazily across his torso. His expression is one of calm, boredom or disinterest.

Room Two contains some very impressive murals, including one of the greatest battle scenes ever depicted in Mesoamerican art. With 139 human figures represented, there is a lot of activity on these walls. The rulers of Bonampak are clear victors in this battle with a proud King Chaan-muan decked out in full jaguar regalia dominating the scene. The losers of the battle have been taken captive and are in various states of punishment, despair and agony. When a viewer enters Room Two, he or she must sit on a bench to view the murals on the north wall. On that bench the ancient Maya artists painted more captives, and thus invite the viewers themselves to participate in the scene of humiliation of the vanquished. Researchers are quick to caution that these scenes are depictions of a Bonampak victory painted by the winning side and may include some propagandized elements and deliberate exaggerations.

Room Three depicts several scenes of the victory celebrations held for the battle shown in Room Two. The three figures from Room One, the three sons of the king, appear here dressed in elaborate costumes of quetzal feathers, including tall headdresses and wings. A curious panel in this room includes a procession of masked musicians who are carrying a dwarf. Another panel shows the beautiful noblewomen of Bonampak, dressed in white and piercing their tongues in auto-sacrifice. A large man attends to the women. A group of 10 lords dressed in white engage in conversation on the north wall. Are they congratulating each other for their victory in battle? Below them, in the bottom register, a group of lively musicians point their instruments to the sky in a very celebratory way. The room is alive with festivities.

Room Three depicts several scenes of the victory celebrations held for the battle shown in Room Two. The three figures from Room One, the three sons of the king, appear here dressed in elaborate costumes of quetzal feathers, including tall headdresses and wings. A curious panel in this room includes a procession of masked musicians who are carrying a dwarf. Another panel shows the beautiful noblewomen of Bonampak, dressed in white and piercing their tongues in auto-sacrifice. A large man attends to the women. A group of 10 lords dressed in white engage in conversation on the north wall. Are they congratulating each other for their victory in battle? Below them, in the bottom register, a group of lively musicians point their instruments to the sky in a very celebratory way. The room is alive with festivities.

The Bonampak murals continue to have an impact on scholarly thought and the popular imagination and have even fueled some fringe theories. When Giles Healey first introduced the outside world to the paintings, they received mixed reactions from archaeologists. Prominent Maya scholars dismissed the engaging battle scene of Room Two because it didn’t go along with the popular view of the ancient Maya at the time. Before this discovery and others depicting warfare among Maya cities, many scholars believed the Maya to be a peaceful people who concerned themselves with chronicling time, observing the heavens and creating beautiful works of art. Sylvanus Morley, one of the principle Maya researchers at the time of the Bonampak murals discovery explained the battle scene in Room Two as a mere raid for slaves that happened rarely between Maya cities. In his book The Ancient Maya, published in 1946, Morley states, “These suggestions of Maya turmoil do not, however, negate the picture of a surprising homogeneity and comparative tranquility in the central Maya area during Classic times.” Now that scholars have deciphered most of the Mayan written language, we know that the Maya world was in constant conflict. As the populations of the cities grew and competition for resources increased, there was increased conflict. Regarding fringe theories, there are certain groups who look to the Bonampak murals as evidence of ancient Mexican contact with Africa. Those who subscribe to this theory note the various skin colors of the people on the walls of the Temple of the Murals. These supposed researchers are not using original source material to formulate their theories but are looking at subsequent artist reinterpretations of the murals. Going back to the original paintings, various degrees of color fading exist,  even after careful restoration. The fact that darker skin colors appear in the work of copyists does not mean that the people depicted on the walls at Bonampak were Africans. The facial structures and dress indicated depictions of indigenous Native Americans painted by Native Americans. No DNA extracted from bones at burials or any cultural artifacts found at the site indicate any ties to Africa at all. Another alternative theory surrounding these murals has to do with the problem of illumination. The rooms with their high vaulted ceilings had no windows or access to light other than what was coming through the doorways. No torches were used while the masters were at work creating these magnificent paintings. So, how did the artists work with such limited light? Some believe that electric or battery-operated lamps provided all the light that the artists needed to work around the clock. Archaeologists believe that artists only worked for an hour or two a day when direct sunlight came through the doors of each room. No evidence of electric or battery-operated lamps have ever been found in the Maya archaeological record, nor have these mysterious lamps ever been depicted in the abundant Maya art that still exists today.

even after careful restoration. The fact that darker skin colors appear in the work of copyists does not mean that the people depicted on the walls at Bonampak were Africans. The facial structures and dress indicated depictions of indigenous Native Americans painted by Native Americans. No DNA extracted from bones at burials or any cultural artifacts found at the site indicate any ties to Africa at all. Another alternative theory surrounding these murals has to do with the problem of illumination. The rooms with their high vaulted ceilings had no windows or access to light other than what was coming through the doorways. No torches were used while the masters were at work creating these magnificent paintings. So, how did the artists work with such limited light? Some believe that electric or battery-operated lamps provided all the light that the artists needed to work around the clock. Archaeologists believe that artists only worked for an hour or two a day when direct sunlight came through the doors of each room. No evidence of electric or battery-operated lamps have ever been found in the Maya archaeological record, nor have these mysterious lamps ever been depicted in the abundant Maya art that still exists today.

The murals at Bonampak are a true wonder of the ancient world representing the apex of Maya art and culture. These paintings, it seems, were the last artistic gasps of a people before their civilization collapsed. No one knows the fates of the famous people depicted on the walls or why exactly everything ended. For now, the Classic Maya collapse remains one of the enduring mysteries of Mexico.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael D. The Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1966. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2Z8KCo9

Morley, Sylvanus. The Ancient Maya. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1946. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2EOCvp1

Weaver, Muriel Porter. The Aztecs, the Maya and their Predecessors. New York: Academic Press, 191. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2EOiH5c