Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

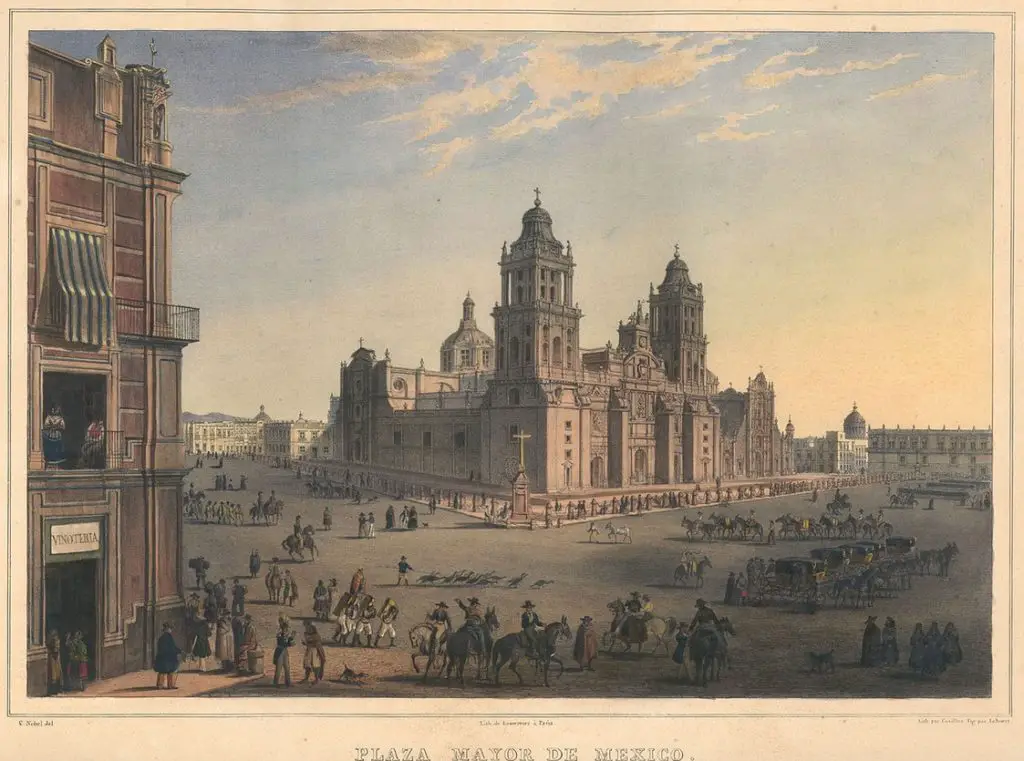

It was a hot day in colonial Mexico City. The date was August 3, 1566. Citizens of the capital of New Spain turned out by the hundreds to bear witness to an important execution of two members of one of the New World’s wealthiest families. Brothers Gil Ávila González and Alonso Ávila Alvarado rode on muleback from the royal prison to the Plaza Mayor to meet their fate. The were the sons of Gil González de Benavides, one of the Spanish soldiers who accompanied conquistador Hernán Cortés on his march to the Aztec capital of Tenonchtitlán in 1519 which was 47 years before this event. As a member of the original group of conquerors, the father of the Ávila brothers was rewarded greatly by the king of Spain who granted him land, the rights to indigenous labor and a hefty payout from the royal treasury. The brothers grew up in great wealth as their father’s empire expanded until he became one of the wealthiest men in the Western Hemisphere. The father’s wealth could not save the two young men who were to face their executioner on that hot summer day in 1566. The older Ávila brother was dressed plainly and cut a grim figure. This was in stark contrast to his younger brother, who was considered one of the handsomest young men in New Spain and dressed accordingly. Official documents record that the younger Ávila brother was wearing satin hose from the Orient and fancy doublets to match. His main garment was lined with panther skins. On his head he wore an elegant cap finished off in gold and colorful feathers. Around his neck he wore a chain, locket and rosary, all made of shiny gold. Several priests raised their voices over the boos and cheers of the crowd, asking the brothers to make their final confession before their heads were to rest on the chopping block. The brothers declined and the execution was swift. The heads of the Ávila brothers were placed on wooden pikes in the middle of the Plaza Mayor for all to see and to serve as a warning to those who would question royal authority. These executions were part of a years-long investigation into a possible plot to kick out the Spanish from New Spain and make Mexico independent some 250+ years before Spain would officially grant Mexico its independence in 1821. Who were involved in this alleged plot? What were some of the reasons behind it?

It was a hot day in colonial Mexico City. The date was August 3, 1566. Citizens of the capital of New Spain turned out by the hundreds to bear witness to an important execution of two members of one of the New World’s wealthiest families. Brothers Gil Ávila González and Alonso Ávila Alvarado rode on muleback from the royal prison to the Plaza Mayor to meet their fate. The were the sons of Gil González de Benavides, one of the Spanish soldiers who accompanied conquistador Hernán Cortés on his march to the Aztec capital of Tenonchtitlán in 1519 which was 47 years before this event. As a member of the original group of conquerors, the father of the Ávila brothers was rewarded greatly by the king of Spain who granted him land, the rights to indigenous labor and a hefty payout from the royal treasury. The brothers grew up in great wealth as their father’s empire expanded until he became one of the wealthiest men in the Western Hemisphere. The father’s wealth could not save the two young men who were to face their executioner on that hot summer day in 1566. The older Ávila brother was dressed plainly and cut a grim figure. This was in stark contrast to his younger brother, who was considered one of the handsomest young men in New Spain and dressed accordingly. Official documents record that the younger Ávila brother was wearing satin hose from the Orient and fancy doublets to match. His main garment was lined with panther skins. On his head he wore an elegant cap finished off in gold and colorful feathers. Around his neck he wore a chain, locket and rosary, all made of shiny gold. Several priests raised their voices over the boos and cheers of the crowd, asking the brothers to make their final confession before their heads were to rest on the chopping block. The brothers declined and the execution was swift. The heads of the Ávila brothers were placed on wooden pikes in the middle of the Plaza Mayor for all to see and to serve as a warning to those who would question royal authority. These executions were part of a years-long investigation into a possible plot to kick out the Spanish from New Spain and make Mexico independent some 250+ years before Spain would officially grant Mexico its independence in 1821. Who were involved in this alleged plot? What were some of the reasons behind it?

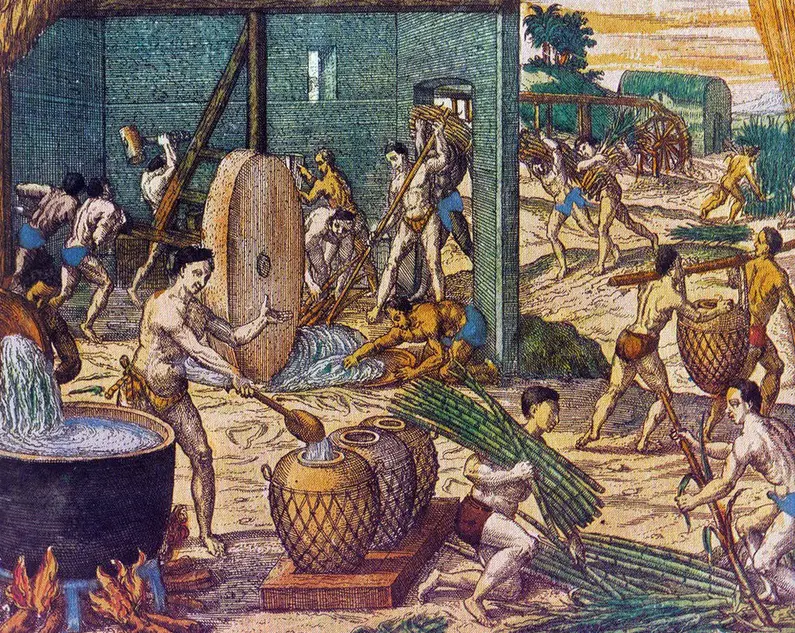

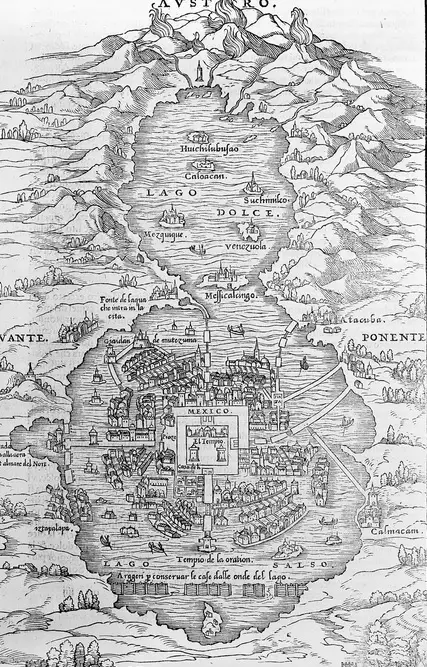

First, we need to define some terms and explain what life was like in Mexico in 1566. By the mid-1500s, New Spain had become a very prosperous colony of Spain. The second generation had come of age – the sons and daughters of the original conquistadors, settlers and colonizers – and made up the brand-new Mexico-born elite class of the colony. Many of these of the second generation were wealthy beyond measure, enjoying privileges and grand lifestyles not seen among the noble class back in Spain. In order to settle the new country, the king of Spain rewarded handsomely the conquerors and the first settlers and colonizers of the newly discovered lands. Many of the first Spaniards in the new land benefitted enormously from the encomienda system. The encomienda system had its origins in medieval Spain’s feudal system. In New Spain, the Spanish king or resident royal authority in the form of the viceroy, would grant large tracts of land to the encomendero which would include a portion of the labor of the indigenous people living on that land. For example, if a large tract of land given to a conquistador included 4 native villages within its boundaries, the grantee or encomendero would get a portion of whatever the labor was produced by the villages and could force any indigenous person within those villages to work for him in whatever capacity at will. One might think that the indigenous people would have revolted in the face of this system of quasi-slavery. The fact is, many peoples who were living under Aztec domination immediately before the Spanish arrived were used to paying tribute to the Aztec emperor or sending people from their villages to the Aztec capital on the whims of the emperor, so this Spanish feudal system was really nothing new. The holders of encomiendas became incredibly affluent, and some men who offered exceptional service to the Spanish Empire became holders of multiple encomiendas. Some encomenderos ruled their lands like private kingdoms, and their children, the second generation, grew up in a fabulous world of incredible wealth.

First, we need to define some terms and explain what life was like in Mexico in 1566. By the mid-1500s, New Spain had become a very prosperous colony of Spain. The second generation had come of age – the sons and daughters of the original conquistadors, settlers and colonizers – and made up the brand-new Mexico-born elite class of the colony. Many of these of the second generation were wealthy beyond measure, enjoying privileges and grand lifestyles not seen among the noble class back in Spain. In order to settle the new country, the king of Spain rewarded handsomely the conquerors and the first settlers and colonizers of the newly discovered lands. Many of the first Spaniards in the new land benefitted enormously from the encomienda system. The encomienda system had its origins in medieval Spain’s feudal system. In New Spain, the Spanish king or resident royal authority in the form of the viceroy, would grant large tracts of land to the encomendero which would include a portion of the labor of the indigenous people living on that land. For example, if a large tract of land given to a conquistador included 4 native villages within its boundaries, the grantee or encomendero would get a portion of whatever the labor was produced by the villages and could force any indigenous person within those villages to work for him in whatever capacity at will. One might think that the indigenous people would have revolted in the face of this system of quasi-slavery. The fact is, many peoples who were living under Aztec domination immediately before the Spanish arrived were used to paying tribute to the Aztec emperor or sending people from their villages to the Aztec capital on the whims of the emperor, so this Spanish feudal system was really nothing new. The holders of encomiendas became incredibly affluent, and some men who offered exceptional service to the Spanish Empire became holders of multiple encomiendas. Some encomenderos ruled their lands like private kingdoms, and their children, the second generation, grew up in a fabulous world of incredible wealth.

By the middle of the 1500s many people in Spain became aware of the unlimited opportunities in New Spain, and that drew the attention of members of the lower ranks of the noble class in Spain who were intrigued by the stories of unlimited riches. Many higher-born Spaniards started to relocate to Mexico but were appalled at what they saw when they got there. Most of the Mexico-born elite class was seen as uppity upstarts in the eyes of the newcomers. Some newly arrived nobles who had spent time at the Spanish court were astonished to see members of the merchant class or landed class living lives better than those of the king and higher-ranking Spanish royalty. The second generation of this New World ruling class not only lacked noble blood and deep family connections back in Europe, but some were also products of mixed-race unions and were either mestizo or mulato. While the Mexico-born elites controlled society and trade in the prosperous colony, the administration of New Spain, the actual government, starting with the viceroy, was composed of political appointees from the nobles classes of Spain who had little experience in the New World. There was an incredible amount of resentment coming from those who just got off the boat toward the descendants of those who pioneered, sacrificed and built New Spain into the land of prosperity that these minor nobles just walked into. The tension between these groups grew. Because of reports from the newcomers going back to the home country, Spain wanted a bigger piece of the wealth to help support its floundering treasury and bloated bureaucracy back home. Then came the New Laws that ended the ability for the encomendero to pass his encomienda down to his children. Under the new legislation, when an encomendero died, his lands and the entirety of his property would revert to the crown, thus enriching Spanish coffers and denying the sons of the encomenderos what was seen as their rightful inheritance. This angered the New Spain elite class. Many people knew that something must be done but didn’t know exactly what to do or how to do it. Enter the son of conquistador Hernán Cortés, a popular and well-connected young man named Martín Cortés.

By the middle of the 1500s many people in Spain became aware of the unlimited opportunities in New Spain, and that drew the attention of members of the lower ranks of the noble class in Spain who were intrigued by the stories of unlimited riches. Many higher-born Spaniards started to relocate to Mexico but were appalled at what they saw when they got there. Most of the Mexico-born elite class was seen as uppity upstarts in the eyes of the newcomers. Some newly arrived nobles who had spent time at the Spanish court were astonished to see members of the merchant class or landed class living lives better than those of the king and higher-ranking Spanish royalty. The second generation of this New World ruling class not only lacked noble blood and deep family connections back in Europe, but some were also products of mixed-race unions and were either mestizo or mulato. While the Mexico-born elites controlled society and trade in the prosperous colony, the administration of New Spain, the actual government, starting with the viceroy, was composed of political appointees from the nobles classes of Spain who had little experience in the New World. There was an incredible amount of resentment coming from those who just got off the boat toward the descendants of those who pioneered, sacrificed and built New Spain into the land of prosperity that these minor nobles just walked into. The tension between these groups grew. Because of reports from the newcomers going back to the home country, Spain wanted a bigger piece of the wealth to help support its floundering treasury and bloated bureaucracy back home. Then came the New Laws that ended the ability for the encomendero to pass his encomienda down to his children. Under the new legislation, when an encomendero died, his lands and the entirety of his property would revert to the crown, thus enriching Spanish coffers and denying the sons of the encomenderos what was seen as their rightful inheritance. This angered the New Spain elite class. Many people knew that something must be done but didn’t know exactly what to do or how to do it. Enter the son of conquistador Hernán Cortés, a popular and well-connected young man named Martín Cortés.

Many saw Martín as the uncrowned king of New Spain. He was born in 1532 on the Cortés properties in Cuernavaca, in the modern Mexican state of Morelos. His mother was Doña Juana de Zúñiga who hailed from middle and lower Spanish noble houses. Her father was the count of Aguilar de Inestrillas and her mother was brother to the Duke of Béjar. Doña Juana de Zúñiga was the third wife of the conquistador Hernán Cortés. His first wife bore him no children and later died. He had a second, more unofficial union with Doña Marina, known as La Malinche, the translator of the expedition to Tenochtitlan. For more information about the Malinche, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 20: https://mexicounexplained.com/mysterious-dona-marina-important-woman-mexican-history/ With Doña Marina, Hernán Cortés had a son, his first son, also named Martín which has confused people over the centuries. This Martín is known as El Mestizo and was seen as “illegitimate” because the conquistador was not officially married to Malinche at the time. The second Martín would later receive the conquistador’s titles and lands and is the topic of discussion here. This Martín grew up in the life of luxury and had an air of superiority and high confidence that irked the Spaniards of noble birth who were arriving to New Spain at the time. This Martín was known as Don Martín because of his rank and importance in the colony. Don Martín spent most of his youth in Spain and as a young man he befriended Prince Philip, son of Spain’s King Charles I. Martín and the prince fought side by side in the rebellious Spanish Netherlands and became friends and confidants. When King Charles abdicated, the prince became King Philip II of Spain, thus giving the young Cortés an ally of the highest kind which he would use later in life. Don Martín and his two brothers returned to New Spain in 1563 and were embraced by all the second-generation New Spain elites who hosted elaborate parties for them. At the time of his return, Don Martín was the richest man in New Spain, as he inherited his father’s multiple encomiendas and the title of Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca. Many saw the mere bravado and arrogant self-confidence of Don Martín as a challenge to the established order. Members of the bureaucratic class of New Spain were keeping a close eye on him.

On July 31, 1564 things would change dramatically for Don Martín Cortés. The viceroy of New Spain, Luís de Velasco, died. While waiting for a replacement to come from Spain, the Mexico City Council elected Don Martín Captain General, thus giving him the governmental power that he had since been lacking.

In the absence of a viceroy, those in the colonial government who resented the Mexico-born wealthy elite class felt worried that they would lose their grip on power. Many of the appointed noble European-born bureaucrats were paranoid and afraid of revolt from the local elite class. Rumors began to circulate about a plot to overthrow Spanish authority coming from the ranks of the encomienda class. Accusations circulated. These accusations led to a series of arrests and unlawful detentions. Many people were tortured to obtain bogus confessions of a plot that included or was headed by Don Martín himself. In all, 89 people were rounded up and accused of participating in this conspiracy. Among them were some of the most influential people in New Spain, including a member of another important family in Mexican history, a man named Cristobal Oñate. His cousin’s son, Juan, would lead the first colonization party to Spanish New Mexico in 1598. Many of the 89 supposed plotters were charged with treason, conspiracy, bribery, extortion, and obstruction of justice, among other things. Punishments assigned to the accused ranged from beheading to banishment to the imposition of fines. Some lost all their property, their reputations and their legacies for their children. It only became evident after some of the executions had taken place that there was no substance to this supposed plot at all. Alleged witnesses were coerced or tortured into saying what the prosecution wanted to hear. There were many procedural issues that were disregarded, such as obtaining testimony of witnesses in court under oath, instead of accepting written statements from witnesses. After the execution of the Ávila brothers mentioned earlier, the wives of the brothers journeyed to Spain and pleaded their husbands’ cases to the crown to try to restore their property and the inheritances due their children. The unrelenting women were successful at court and helped bring the many injustices of the conspiracy trial to light.

In the absence of a viceroy, those in the colonial government who resented the Mexico-born wealthy elite class felt worried that they would lose their grip on power. Many of the appointed noble European-born bureaucrats were paranoid and afraid of revolt from the local elite class. Rumors began to circulate about a plot to overthrow Spanish authority coming from the ranks of the encomienda class. Accusations circulated. These accusations led to a series of arrests and unlawful detentions. Many people were tortured to obtain bogus confessions of a plot that included or was headed by Don Martín himself. In all, 89 people were rounded up and accused of participating in this conspiracy. Among them were some of the most influential people in New Spain, including a member of another important family in Mexican history, a man named Cristobal Oñate. His cousin’s son, Juan, would lead the first colonization party to Spanish New Mexico in 1598. Many of the 89 supposed plotters were charged with treason, conspiracy, bribery, extortion, and obstruction of justice, among other things. Punishments assigned to the accused ranged from beheading to banishment to the imposition of fines. Some lost all their property, their reputations and their legacies for their children. It only became evident after some of the executions had taken place that there was no substance to this supposed plot at all. Alleged witnesses were coerced or tortured into saying what the prosecution wanted to hear. There were many procedural issues that were disregarded, such as obtaining testimony of witnesses in court under oath, instead of accepting written statements from witnesses. After the execution of the Ávila brothers mentioned earlier, the wives of the brothers journeyed to Spain and pleaded their husbands’ cases to the crown to try to restore their property and the inheritances due their children. The unrelenting women were successful at court and helped bring the many injustices of the conspiracy trial to light.

Don Martín Cortés also went to Spain to plead his case and was severely sanctioned despite there being no concrete evidence against him. His friend the king spared his life but the monarch needed to send a message to others who would think of plotting real rebellions against him in his overseas realms. King Philip II divested Don Martín of most of his immense holdings. Although Cortés spent most of his life fighting to get back what was his, the little he had left was eventually handed down to his son who also received his title of Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca. Don Martín eventually died in Spain in the year 1589 never seeing his beloved homeland again.

REFERENCES

Flint, Shirley Cushing. “Treason or Travesty: The Martín Cortés Conspiracy Reexamined.” The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, 2008