Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

People the world over are fascinated with the Classic Maya. The monumental architecture of their impressive cities draws countless tourists to these fascinating Mesoamerican sites. At the height of its civilization, the ancient Maya were masters in astronomy, art, and mathematics. Their writing system survives to tell tales of kings and battles and homage paid to the gods. By 900 AD most of Classic Maya civilization had collapsed and a majority of the once-mighty cities were abandoned. There was a brief renaissance of Maya culture at the famous city of Chichén Itzá after most of its neighbors fell apart but by about 1100 AD that city, too, had been abandoned. The high civilization associated with ancient people was never to be seen again after this time. So, what happened in the Maya area between the disintegration of Chichén Itzá in the 12th Century and the arrival of the Europeans in the early 1500s?

People the world over are fascinated with the Classic Maya. The monumental architecture of their impressive cities draws countless tourists to these fascinating Mesoamerican sites. At the height of its civilization, the ancient Maya were masters in astronomy, art, and mathematics. Their writing system survives to tell tales of kings and battles and homage paid to the gods. By 900 AD most of Classic Maya civilization had collapsed and a majority of the once-mighty cities were abandoned. There was a brief renaissance of Maya culture at the famous city of Chichén Itzá after most of its neighbors fell apart but by about 1100 AD that city, too, had been abandoned. The high civilization associated with ancient people was never to be seen again after this time. So, what happened in the Maya area between the disintegration of Chichén Itzá in the 12th Century and the arrival of the Europeans in the early 1500s?

From the ashes of the old city states and dynasties of the Yucatán emerged what archaeologists and historians refer to as the League of Mayapán. Researchers are still unclear how to label this “League.” Was it a group of associated states? Was it a confederation? Was it a series of chiefdoms or primitive kingdoms whose rulers were interrelated? It seems that after Chichén Itzá collapsed, there was a void to fill and the city of Mayapán rose to the occasion. According to native sources after the Conquest, this city was built after the surviving Maya nobility in the Yucatán decided to come together and construct a regional capital city. The city still exists today, in ruins and open to the public, located 25 miles southeast of Merida, the modern-day capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. The construction of Mayapán took place around 1150 AD. No written records – no glyphs or complete texts on monumental architecture – exist from this time to give exact dates or the exact form of government. Archaeologists are still trying to work out the timeline of events in the early phases of the League of Mayapán. According to oral histories recorded by the Spanish, the first king of  Mayapán who was tasked with overseeing the administration of this loose confederation of allied states, came from the Cocom family, a wealthy and powerful royal line that stretched back to the Classic Maya civilization of the pre-900s. Royal families ruling the associated states were obligated to send one member to Mayapán to serve on an administrative council for the league. Some researchers believe that these royal delegates were also potential hostages used in political bargaining if their respective states ever got out of line. Some oral accounts of Mayapán also mention the Xiu family along with the Cocoms. The Xius supposedly ruled the area around the new city of Mayapán long before the Cocoms rose to prominence. Some stories claim that the Xius were the direct descendants of the rulers of Uxmal and had dominated the western Yucatán since around 500 AD. For more information about this ancient Maya site, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 185 “Uxmal, Lost City of the Dwarf” https://mexicounexplained.com/uxmal-lost-city-of-the-dwarf/ In any case, the council made up of the noble representatives most likely ruled the league, headed by a member of the Cocom family as a sort of paramount ruler or administrator. That position of the supreme ruler was formally called the Jalach winik. He most likely shared some of his power with the aj k’in or high priest. The noble representatives who came from the various regions of the Yucatán to serve on the council most likely had specific roles they filled, much like heads of committees in modern democratic republics. There was probably a lot of infighting and rivalry at Mayapán by these nobles who were jockeying for positions or busy currying favors. It is unknown to what degree the relationships among the federated city states were antagonistic or peaceful. Archaeologists do know for sure that in the mid-1400s the city of Mayapán was sacked, burned, and abandoned. Oral tradition surviving after the Spanish Conquest claims that a member of the Xiu family named Ah Xupan led a rebellion in which the city was destroyed and every member of the Cocom family was executed except for one of the sons of the king who was on a diplomatic mission to a small Maya kingdom located in modern-day Honduras. According to these oral tales, this all happened in the year 1441 which would loosely correlate to the archaeological evidence that the city of Mayapán was burned to the ground sometime in the mid-1400s. After a good run of about 300 years, the League of Mayapán dissolved and a new political structure would emerge in the Yucatán Peninsula.

Mayapán who was tasked with overseeing the administration of this loose confederation of allied states, came from the Cocom family, a wealthy and powerful royal line that stretched back to the Classic Maya civilization of the pre-900s. Royal families ruling the associated states were obligated to send one member to Mayapán to serve on an administrative council for the league. Some researchers believe that these royal delegates were also potential hostages used in political bargaining if their respective states ever got out of line. Some oral accounts of Mayapán also mention the Xiu family along with the Cocoms. The Xius supposedly ruled the area around the new city of Mayapán long before the Cocoms rose to prominence. Some stories claim that the Xius were the direct descendants of the rulers of Uxmal and had dominated the western Yucatán since around 500 AD. For more information about this ancient Maya site, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 185 “Uxmal, Lost City of the Dwarf” https://mexicounexplained.com/uxmal-lost-city-of-the-dwarf/ In any case, the council made up of the noble representatives most likely ruled the league, headed by a member of the Cocom family as a sort of paramount ruler or administrator. That position of the supreme ruler was formally called the Jalach winik. He most likely shared some of his power with the aj k’in or high priest. The noble representatives who came from the various regions of the Yucatán to serve on the council most likely had specific roles they filled, much like heads of committees in modern democratic republics. There was probably a lot of infighting and rivalry at Mayapán by these nobles who were jockeying for positions or busy currying favors. It is unknown to what degree the relationships among the federated city states were antagonistic or peaceful. Archaeologists do know for sure that in the mid-1400s the city of Mayapán was sacked, burned, and abandoned. Oral tradition surviving after the Spanish Conquest claims that a member of the Xiu family named Ah Xupan led a rebellion in which the city was destroyed and every member of the Cocom family was executed except for one of the sons of the king who was on a diplomatic mission to a small Maya kingdom located in modern-day Honduras. According to these oral tales, this all happened in the year 1441 which would loosely correlate to the archaeological evidence that the city of Mayapán was burned to the ground sometime in the mid-1400s. After a good run of about 300 years, the League of Mayapán dissolved and a new political structure would emerge in the Yucatán Peninsula.

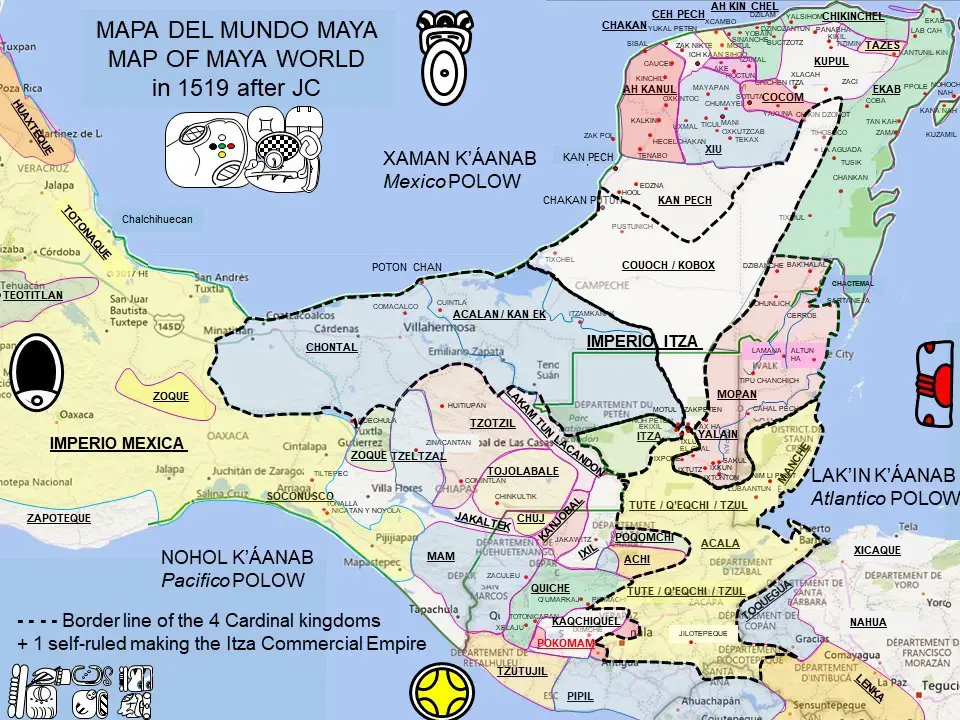

After the fall of Mayapán, the Yucatán reorganized itself into a group of 17 independent kingdoms or chiefdoms called Kuchkabals. A Kuchkabal was divided into municipalities or counties called betalibs ruled by a batab, who was also a military leader. Each Kuchkabal was headed by a male ruler called Halach Uinik, but some of these new countries experimented with a more representational form of government. A few were ruled, at various times in their histories, by what would look somewhat like a modern-day Senate or House of Representatives. The betalibs, or counties, would send delegates to the capital city to sit in the legislative body to rule the Kuchkabal instead of being subject to an absolute monarch. Most of these new political entities were ruled by one strongman or a small group of leaders from the old noble families. Here are the names of the 17 Kuchkabals of the pre-Hispanic Yucatán: Ekab, Chakan Putum, Ah Canul, Ceh Pech, Tutul-Xiu, Sotuta, Hocaba, Chakan, Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, Tazes, Chickinchel, Uaymil, Chetumal, Cochuah, Can Pech and Calotmul. Each Kuchkabal was fully independent. Each had a capital city that was the center of commerce and government, but these cities did not even come close to the monumental stone metropolises of the Classic Maya of 500 years before. It is not known if or to what extent that these political entities had treaties of friendship, economic relations, or formal alliances among one another. From the oral traditions and the physical evidence found in the archaeological record, the Kuchkabals of the Yucatán did war amongst themselves. Boundaries between these polities may have been shifting or very ambiguous, especially in dense forest territory. It is almost impossible for modern researchers to draw solid lines on a map to delineate the Kuchkabals.

After the fall of Mayapán, the Yucatán reorganized itself into a group of 17 independent kingdoms or chiefdoms called Kuchkabals. A Kuchkabal was divided into municipalities or counties called betalibs ruled by a batab, who was also a military leader. Each Kuchkabal was headed by a male ruler called Halach Uinik, but some of these new countries experimented with a more representational form of government. A few were ruled, at various times in their histories, by what would look somewhat like a modern-day Senate or House of Representatives. The betalibs, or counties, would send delegates to the capital city to sit in the legislative body to rule the Kuchkabal instead of being subject to an absolute monarch. Most of these new political entities were ruled by one strongman or a small group of leaders from the old noble families. Here are the names of the 17 Kuchkabals of the pre-Hispanic Yucatán: Ekab, Chakan Putum, Ah Canul, Ceh Pech, Tutul-Xiu, Sotuta, Hocaba, Chakan, Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, Tazes, Chickinchel, Uaymil, Chetumal, Cochuah, Can Pech and Calotmul. Each Kuchkabal was fully independent. Each had a capital city that was the center of commerce and government, but these cities did not even come close to the monumental stone metropolises of the Classic Maya of 500 years before. It is not known if or to what extent that these political entities had treaties of friendship, economic relations, or formal alliances among one another. From the oral traditions and the physical evidence found in the archaeological record, the Kuchkabals of the Yucatán did war amongst themselves. Boundaries between these polities may have been shifting or very ambiguous, especially in dense forest territory. It is almost impossible for modern researchers to draw solid lines on a map to delineate the Kuchkabals.

The wealthiest and most powerful of the post-League of Mayapán chiefdoms was Cupul. Located in the north-central part of the peninsula, Cupul’s territory included Chichén Itzá which was still being occupied even though it had lost its glory centuries before. For most of its history Cupul was landlocked and fought with its neighbor to the north – Chikinchel – for access to the sea. There is record of Cupul at one point having access to or at least permission to access the salt beds on the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, but this may have been temporary or Cupul might have lost a small war with its northern neighbor that ended its access in a more formal way. Cupul’s capital city of Zakí would later become the Spanish city of Valladolid which is now one of Mexico’s pueblos magicos renowned for its colonial charm.

While Cupul was the wealthiest and most powerful of the Kuchkabals, the northeastern kingdom of Ekab was probably the most important because it contained famous and popular religious pilgrimage sites. Ekab was one of the Kuchkabals that had a representative government in the form of a legislative body made up of the batabs or rulers of the municipalities or counties. The legislative body met at the capital city of Ekab located on the coast in the far northeastern corner of the Yucatán Peninsula. While the districts, or betalibs, making up the country of Ekab were supposed to be equal, the betalib of Cozumel was the most influential at the national level due to the pilgrimage sites mentioned earlier. The island of Cozumel attracted worshippers from as far away as modern-day Nicaragua and Michoacán in western Mexico. The pilgrims were paying homage to the moon goddess Ix Chel, who was also the patroness of childbirth, weaving and medicine. On the island there was a temple and a statue to Ix Chel where worshippers, mostly women, would listen to an oracle who was a priest sitting inside the statue. For more information about this goddess, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 78: https://mexicounexplained.com/moon-goddesses-ancient-mexicans/

Another Kuchkabal of note worth mentioning was Chakán Putum, located in the southwestern part of the Yucatán. This Kuchkabal was the largest, and its land area comprised over 20% of all the land of the Kuchkabals. It’s capital city, also called Chakán Putum, was described by the first Europeans to see it, as “a city of 8,000 houses.” Chakán Putum was resource rich, and its most economically viable product was fish. A fleet of 2000 boats would go out into the Gulf of Mexico to fish and since the country had many navigable rivers and lakes, fishing was important in the interior of Chakán Putum as well. The territory of this political entity bordered the lands of the Chontal Maya to the southwest, a loose association of villages and small cities with a much weaker and more informal political structure than that of the Kuchkabals of the Yucatán.

Another Kuchkabal of note worth mentioning was Chakán Putum, located in the southwestern part of the Yucatán. This Kuchkabal was the largest, and its land area comprised over 20% of all the land of the Kuchkabals. It’s capital city, also called Chakán Putum, was described by the first Europeans to see it, as “a city of 8,000 houses.” Chakán Putum was resource rich, and its most economically viable product was fish. A fleet of 2000 boats would go out into the Gulf of Mexico to fish and since the country had many navigable rivers and lakes, fishing was important in the interior of Chakán Putum as well. The territory of this political entity bordered the lands of the Chontal Maya to the southwest, a loose association of villages and small cities with a much weaker and more informal political structure than that of the Kuchkabals of the Yucatán.

August 14, 1502, marked the beginning of the end of the Kuchkabals, just 60 years after the fall of the League of Mayapán. Christopher Columbus onboard the Santa María during his 4th voyage to the New World anchored off the coast of modern-day Honduras. It was there where he encountered a merchant vessel from the Kuchkabal of Ekab. Word spread throughout the Maya world of the arrival of these foreigners. Nine years after Columbus, in 1511, a Spanish ship plying the Caribbean was caught in a storm and shipwrecked on Ekab territory. The survivors of the vessel were captured by the Maya and sold into slavery. In 1517 Francisco Hernández de Córdoba landed on Isla Mujeres, also in Ekab territory, and from there explored the interior of the Yucatán, encountering fierce resistance. Famous conquistador Hernán Cortés even stopped on the shores of the Kuchkabal Ekab on his way to conquer the Aztecs. After the subjugation of the Aztec Empire, Spanish interest in the Yucatán grew and between 1527 and 1547 the entire peninsula was conquered. Thus ended a somewhat brief experiment of independent chiefdoms and indigenous autonomy in general in the Yucatán.

REFERENCES

Andrews, Anthony P. “The Political Geography of the Sixteenth Century Yucatan Maya: Comments and Revisions.” In Journal of Anthropological Research 40 (4): 589-596. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, Winter 1984.

Coe, Michael D. The Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993. We are Amazon affiliates. Purchase the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3GfEBvG

One thought on “The Maya World Between Collapse and Conquest”

this article is very useful, thank you for making a good article