Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

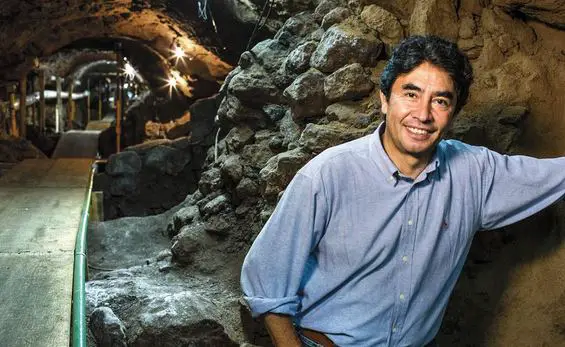

In the fall of the year 2003, a massive rainstorm swept over Teotihuacán, a pre-Aztec ancient city located 30 miles northeast of modern-day Mexico City. The rain caused mudflows and severe flooding at the site, a city that had withstood similar deluges in its 2,000-year history. An archaeologist for Mexico’s National Institute for Anthropology and History, Sergio Gómez, came in to work the day after the storm to survey the damage. Gómez noticed something interesting on the side of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, sometimes referred to as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl or the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl. The city’s third largest pyramid, on the southern terminus of the Avenue of the Dead, is home to carvings of plumed serpents and is part of the Ciudadela or Citadel complex. On the side of the temple Gómez discovered a sinkhole measuring about 3 feet across. The archaeologist got closer to the hole but was afraid of weakened earth around it, so he stood on part of the temple closest to the hole and shone a flashlight into the dark pit. He couldn’t make out anything, so he asked his colleagues to lower him down into a hole with a rope tied around his waist. Gómez found himself in the middle of a manmade tunnel with two ends blocked off by huge boulders. Digging would start 6 years later. Although this wasn’t the first tunnel to be discovered existing under the ruined city of Teotihuacán, what the Gómez team would eventually find would be considered one of the most important discoveries at an ancient Mexican site ever made.

In the fall of the year 2003, a massive rainstorm swept over Teotihuacán, a pre-Aztec ancient city located 30 miles northeast of modern-day Mexico City. The rain caused mudflows and severe flooding at the site, a city that had withstood similar deluges in its 2,000-year history. An archaeologist for Mexico’s National Institute for Anthropology and History, Sergio Gómez, came in to work the day after the storm to survey the damage. Gómez noticed something interesting on the side of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, sometimes referred to as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl or the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl. The city’s third largest pyramid, on the southern terminus of the Avenue of the Dead, is home to carvings of plumed serpents and is part of the Ciudadela or Citadel complex. On the side of the temple Gómez discovered a sinkhole measuring about 3 feet across. The archaeologist got closer to the hole but was afraid of weakened earth around it, so he stood on part of the temple closest to the hole and shone a flashlight into the dark pit. He couldn’t make out anything, so he asked his colleagues to lower him down into a hole with a rope tied around his waist. Gómez found himself in the middle of a manmade tunnel with two ends blocked off by huge boulders. Digging would start 6 years later. Although this wasn’t the first tunnel to be discovered existing under the ruined city of Teotihuacán, what the Gómez team would eventually find would be considered one of the most important discoveries at an ancient Mexican site ever made.

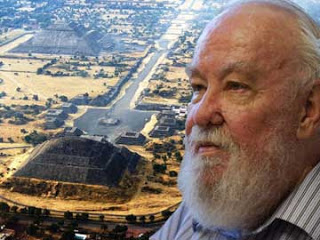

Considered to be the grandfather of Teotihuacán research, American archaeologist George Cowgill gives a good summary of the ancient city in the introduction to his scholarly paper, “Ritual Sacrifice and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacán, México.” Here are the words of the late Professor Cowgill:

“Teotihuacán is an immense Mesoamerican city that flourished in the Basin of México between about 100 B.C.E. and 650 C.E. For much of that time it covered about 20 square kilometers, with a population estimated around 100,000. Arrayed for over two kilometers along the broad Avenue of the Dead are the immense Sun and Moon Pyramids, the Ciudadela complex, and scores of smaller complexes of pyramids, platforms, and plazas. Surrounding this are over 2000 sizable and substantially built multi-apartment residential compounds. The extent of territory politically subjugated by Teotihuacán is still unclear, but its influences are manifest throughout nearly all of Mesoamerica. After more than a century of archaeological work, most of the ancient city remains unexcavated, and only a tiny fraction has been excavated according to modern standards.”

For a more general overview of Teotihuacán, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 45. https://mexicounexplained.com//teotihuacan-lost-city-gods/

The Aztecs came upon a ruined Teotihuacán some six centuries after the city was abandoned. In the Codex Xolotl, an Aztec illustrated bark-paper book, Teotihuacán is represented by a glyph showing two pyramids over a cave with a person inside it. The Aztecs must have known of the cave and tunnel system underneath the ancient city long before the French archaeologist Desiré Charney explored the underground labyrinths in the 1870s. Local guides took Charney through a vast network of natural and manmade caverns. The Frenchman theorized that most of what he was seeing were remnants of ancient quarries where stones were cut to build the monumental architecture of the ancient city. He also noted that in some of the caves he saw stacks of bones, and possibly reminded of European catacombs, Charney thought that these vast underground spaces served the same purpose. In his book, Les anciennes villes du Nouveau Mond, or in English, “The Ancient Cities of the New World,” Charney describes an extensive network of caverns, large galleries and a rotunda filled with bones and artifacts. Another tunnel, whose entrance was a little over a mile from the Pyramid of the Sun, seemed to head toward the great pyramid in a straight line. Charney could only make it through a half mile into the tunnel and noted that it seemed to go on forever leading some to believe that it was a straight shot to some chambers underneath the city’s largest pyramid. The entrance to this long tunnel has not been rediscovered. In Charney’s day there were also rumors of a 40-mile-long tunnel heading out of the city to the southeast connecting Teotihuacán to the town of Amecameca at the foot of the snow-covered volcano Iztaccíhuatl. The existence of that tunnel has never been verified

The Aztecs came upon a ruined Teotihuacán some six centuries after the city was abandoned. In the Codex Xolotl, an Aztec illustrated bark-paper book, Teotihuacán is represented by a glyph showing two pyramids over a cave with a person inside it. The Aztecs must have known of the cave and tunnel system underneath the ancient city long before the French archaeologist Desiré Charney explored the underground labyrinths in the 1870s. Local guides took Charney through a vast network of natural and manmade caverns. The Frenchman theorized that most of what he was seeing were remnants of ancient quarries where stones were cut to build the monumental architecture of the ancient city. He also noted that in some of the caves he saw stacks of bones, and possibly reminded of European catacombs, Charney thought that these vast underground spaces served the same purpose. In his book, Les anciennes villes du Nouveau Mond, or in English, “The Ancient Cities of the New World,” Charney describes an extensive network of caverns, large galleries and a rotunda filled with bones and artifacts. Another tunnel, whose entrance was a little over a mile from the Pyramid of the Sun, seemed to head toward the great pyramid in a straight line. Charney could only make it through a half mile into the tunnel and noted that it seemed to go on forever leading some to believe that it was a straight shot to some chambers underneath the city’s largest pyramid. The entrance to this long tunnel has not been rediscovered. In Charney’s day there were also rumors of a 40-mile-long tunnel heading out of the city to the southeast connecting Teotihuacán to the town of Amecameca at the foot of the snow-covered volcano Iztaccíhuatl. The existence of that tunnel has never been verified

.

In the 1950s, French-American archaeologist René Millon theorized that the gigantic Pyramid of the Sun sat atop various subterranean chambers and a possible tunnel network. He began digging and found an underground blocked pit that he thought would lead to a gigantic tomb or elaborate royal burial. Millon stopped digging short of his goal of finding anything of consequence let alone the tunnel system he had hoped for. In 1971 archaeologists took Millon’s idea and started looking for a tunnel system connected with the Pyramid of the Sun. They did find an entrance to a tunnel that ran for over 300 feet. The tunnel took them to a series of chambers that branched off into the shape of a four-leaf clover which sat directly under the pyramid. Although blocked off, the tunnel had been accessed in ancient times and the chambers had been looted probably by either Toltec or Aztec treasure seekers. The 1971 archaeological team only found pottery fragments and small flecks of obsidian in the large clover-leaf shaped caverns. There was no elaborate tomb ala King Tut that René Millon had hoped to find decades before.

The tunnels underneath the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacán are a more recent discovery and have yet to be explored. The Moon pyramid is the second-largest pyramid at the site, located at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead and in front of the Plaza of the Moon. Burials have been found inside the pyramid which may have included sacrificial remains. Some of the remains have deformed skulls and were buried with grave objects made of green stone and jewelry. In 2018 tunnels and a chamber measuring 49 feet in diameter were discovered underneath the pyramid without ever using a pickaxe or shovel. Researchers from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History and the Institute of Geophysics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, mapped an image of the area beneath the Pyramid of the Moon using a technique called electrical resistance technology. About 26 feet beneath the pyramid they discovered the large chamber and a system of tunnels connected to it. Mexican archaeologist Verónica Ortega, director of the Integral Conservation Project for the Plaza of the Moon, believes that what her team will find inside the main chamber will most likely be more of what has been discovered already: burials and associated funerary objects. The conservation project is still in the process of submitting the proper plans and other paperwork to the Mexican authorities to do some actual digging. To use the process at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent as an example, Ortega may be waiting a good 5 years or more to get the various permits and permissions needed to do real physical excavations and investigations.

The tunnels underneath the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacán are a more recent discovery and have yet to be explored. The Moon pyramid is the second-largest pyramid at the site, located at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead and in front of the Plaza of the Moon. Burials have been found inside the pyramid which may have included sacrificial remains. Some of the remains have deformed skulls and were buried with grave objects made of green stone and jewelry. In 2018 tunnels and a chamber measuring 49 feet in diameter were discovered underneath the pyramid without ever using a pickaxe or shovel. Researchers from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History and the Institute of Geophysics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, or UNAM, mapped an image of the area beneath the Pyramid of the Moon using a technique called electrical resistance technology. About 26 feet beneath the pyramid they discovered the large chamber and a system of tunnels connected to it. Mexican archaeologist Verónica Ortega, director of the Integral Conservation Project for the Plaza of the Moon, believes that what her team will find inside the main chamber will most likely be more of what has been discovered already: burials and associated funerary objects. The conservation project is still in the process of submitting the proper plans and other paperwork to the Mexican authorities to do some actual digging. To use the process at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent as an example, Ortega may be waiting a good 5 years or more to get the various permits and permissions needed to do real physical excavations and investigations.

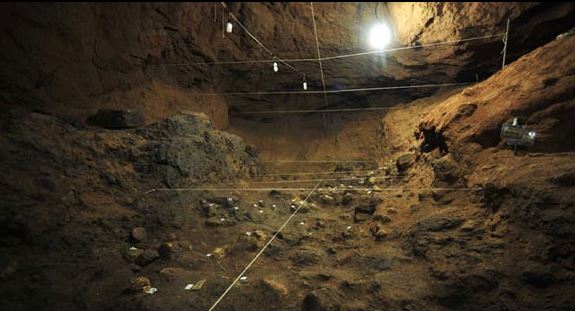

And what exactly became of Sergio Gómez and his team at the Temple of the Feathered Serpent? What were those important discoveries? The sinkhole that appeared in the fall of 2003 was not the entrance to the tunnel leading under the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. With the same ground penetrating radar later used at the Pyramid of the Moon, Gómez and his team spent years thoroughly mapping the subsurface tunnels and chambers before they had permission to dig. They also used two small robots, called Tlaloc I and Tlaloc II to explore the tunnels before humans ventured into them. The robots were equipped with infrared cameras and laser scanners that produced 3-D images to assist the archaeologists in mapping. By September of 2010 Gómez and a team of 30 highly trained specialists were the first people in the temple’s tunnels in perhaps 1,800 years. They entered the vertical shaft entrance which went down over 30 feet deep and was located only about 6 feet from one of the sides of the building. The tunnel that connects to the bottom of the entrance shaft goes nearly 300 feet until it ends in a series of underground chambers. Excavation of the tunnels was done at a snail’s pace and with extreme care. Small hand shovels were used in many instances and dirt was carefully sifted for even the tiniest of artifact fragments. At the end of the excavation process over 1,000 tons of dirt and rock had been removed over the course of many months. The intense manual labor and the great deal of time it had taken over the seven years from discovery to completion of the excavation was definitely worth it. What Gómez and his team discovered was absolutely breathtaking, at least to archaeologists.

The long tunnel ended in two large chambers, the North Chamber and the South Chamber. The walls and the ceilings of these large rooms were coated in a glitter of magnetite, hematite and iron pyrite, or fool’s gold. When light shines on these surfaces, it almost looks like one is looking at the shimmering stars of the night sky. The floors of the chambers were made to look like miniature landscapes, with little mountain peaks and valleys, complete with small stream beds and lakes filled with liquid mercury, a rare find but not entirely unheard of in ancient Mexico. They teotihuacanos made the liquid mercury by crushing cinnabar ore, heating it, creating vaporized mercury, and then gathering its condensation in liquid. Situated in this miniature landscape were 4 small greenstone statues looking up at one focal point on the ceiling, perhaps at the very point where the ancients believed where the various planes of the universe meet. In their sifting of the soils  and throughout their general exploration of the tunnel and chambers, the archaeological team found some 100,000 objects and pieces of objects. These included a wide array of things: Bones of gigantic cats, wooden masks with jade inlays, necklaces, rings, human figurines, crocodile teeth, exotic shells from the Caribbean, jaguar carvings, crystals carved into human eyes, pottery of all shapes and sizes, and even a box containing an arrangement of beetle wings. Although there were fragments of human skin discovered, there were no other human remains or burials. Perhaps the most curious discovery was an abundance of small metalized spheres, hundreds of them, found in the North and South Chambers. They measured from a fraction of an inch to over 5 inches across. Called by some, “mini disco balls,” these small globes were made of clay and coated with jarosite a golden mineral formed in ore deposits by the oxidation of iron sulfides, specifically pyrite. The esteemed Teotihuacán researcher, Professor George Cowgill, although not part of the Gómez project team gave statements to the press about the strange spheres. Cowgill said, “Pyrite was certainly used by the teotihuacanos and other ancient Mesoamerican societies. Originally the spheres would have shone brilliantly. They are indeed unique, but I have no idea what they mean.” Since Cowgill’s remarks a few people have stepped up to offer alternative theories on what these small shiny orbs were used for. Were they sacred offerings to the gods? Did they serve as some sort of currency or measure of wealth? Were they used to illuminate the dark tunnels and chambers somehow like lightbulbs? What Cowgill said a few decades ago still holds true today: only a fraction is known about the history and culture of the ancient city of Teotihuacán. A site of this magnitude requires a great deal of work. Perhaps in a few years the story will be clearer when Verónica Ortega gets the green light on her project and her team is allowed to explore the newly found tunnels under the Pyramid of the Moon. What will eventually be found in those tunnels and chambers may completely change our understanding of this magnificent civilization, or it may just further intensify the mystery.

and throughout their general exploration of the tunnel and chambers, the archaeological team found some 100,000 objects and pieces of objects. These included a wide array of things: Bones of gigantic cats, wooden masks with jade inlays, necklaces, rings, human figurines, crocodile teeth, exotic shells from the Caribbean, jaguar carvings, crystals carved into human eyes, pottery of all shapes and sizes, and even a box containing an arrangement of beetle wings. Although there were fragments of human skin discovered, there were no other human remains or burials. Perhaps the most curious discovery was an abundance of small metalized spheres, hundreds of them, found in the North and South Chambers. They measured from a fraction of an inch to over 5 inches across. Called by some, “mini disco balls,” these small globes were made of clay and coated with jarosite a golden mineral formed in ore deposits by the oxidation of iron sulfides, specifically pyrite. The esteemed Teotihuacán researcher, Professor George Cowgill, although not part of the Gómez project team gave statements to the press about the strange spheres. Cowgill said, “Pyrite was certainly used by the teotihuacanos and other ancient Mesoamerican societies. Originally the spheres would have shone brilliantly. They are indeed unique, but I have no idea what they mean.” Since Cowgill’s remarks a few people have stepped up to offer alternative theories on what these small shiny orbs were used for. Were they sacred offerings to the gods? Did they serve as some sort of currency or measure of wealth? Were they used to illuminate the dark tunnels and chambers somehow like lightbulbs? What Cowgill said a few decades ago still holds true today: only a fraction is known about the history and culture of the ancient city of Teotihuacán. A site of this magnitude requires a great deal of work. Perhaps in a few years the story will be clearer when Verónica Ortega gets the green light on her project and her team is allowed to explore the newly found tunnels under the Pyramid of the Moon. What will eventually be found in those tunnels and chambers may completely change our understanding of this magnificent civilization, or it may just further intensify the mystery.

This show is dedicated to Dr. George Cowgill (1929-2018). I was lucky enough to have him as my professor twice and even had the privilege of a few long discussions with him in his office. I appreciated your gently wisdom and your many contributions (and your wry sense of humor!). RIP.

This show is dedicated to Dr. George Cowgill (1929-2018). I was lucky enough to have him as my professor twice and even had the privilege of a few long discussions with him in his office. I appreciated your gently wisdom and your many contributions (and your wry sense of humor!). RIP.

REFERENCES

Cowgill, George. “Ritual Sacrifice and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid at Teotihuacán, México,” FAMSI, 2002.

El Templo de Quetzalcóatl. Arqueología Mexicana 1(1):21-26, 1993 (In Spanish)

Rossella Lorenz. “Robot Finds Mysterious Spheres in Ancient Temple.” NBC.com, 30 Apr 2013.

Wikipedia

One thought on “The Mysterious Tunnels of Teotihuacán”

Bien hecho, macho 😉 Pero sería más interesante y valuable para todos, si también traduces tu página web a los idiomas mas favoritos: espaniol, frances, alemán, japonés, chino