Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

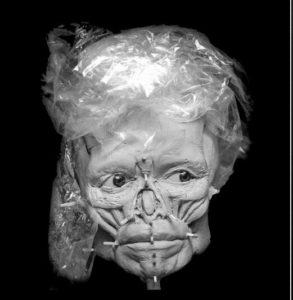

In the year 2010, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History asked Élisabeth Daynès, a noted French sculptor, to help bring life to bones recently uncovered in the Yucatán. In her sunlight-filled studio in Paris, Daynès approached her task seriously. This was not the first time she was asked to reconstruct a face from a mere skull. In her sculpting career spanning over 25 years she took on many interesting assignments, including one from National Geographic five years before to rebuild the face of Ancient Egypt’s King Tut. The Mexican skull was part of the remains of what paleoanthropologists have called La Señora de las Palmas, or “The Lady of Las Palmas,” in English. The skull before Daynès presented her with some interesting questions, and over the course of the few weeks that she worked on the face the artist’s mind wandered. Before her were the remains of a woman who lived before the last Ice Age ended, possibly 13,000 years ago. Scientists concluded that the Señora de las Palmas had died when she was in her mid forties to early fifties, slightly older than Élisabeth Daynès herself. Did this prehistoric Mexican woman live to see her great-grandchildren? As a woman living so long ago, what was her everyday life like? As someone of this advanced age for her times, was she a wise leader of her people? Daynès finished her work ahead of schedule, much to the delight of her employers back in Mexico City. Later that year, for her work on the Señora de las Palmas and other projects, Élisabeth Daynès would win the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize, the most prestigious award given to artists in science art related to paleontology.

In the year 2010, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History asked Élisabeth Daynès, a noted French sculptor, to help bring life to bones recently uncovered in the Yucatán. In her sunlight-filled studio in Paris, Daynès approached her task seriously. This was not the first time she was asked to reconstruct a face from a mere skull. In her sculpting career spanning over 25 years she took on many interesting assignments, including one from National Geographic five years before to rebuild the face of Ancient Egypt’s King Tut. The Mexican skull was part of the remains of what paleoanthropologists have called La Señora de las Palmas, or “The Lady of Las Palmas,” in English. The skull before Daynès presented her with some interesting questions, and over the course of the few weeks that she worked on the face the artist’s mind wandered. Before her were the remains of a woman who lived before the last Ice Age ended, possibly 13,000 years ago. Scientists concluded that the Señora de las Palmas had died when she was in her mid forties to early fifties, slightly older than Élisabeth Daynès herself. Did this prehistoric Mexican woman live to see her great-grandchildren? As a woman living so long ago, what was her everyday life like? As someone of this advanced age for her times, was she a wise leader of her people? Daynès finished her work ahead of schedule, much to the delight of her employers back in Mexico City. Later that year, for her work on the Señora de las Palmas and other projects, Élisabeth Daynès would win the John J. Lanzendorf PaleoArt Prize, the most prestigious award given to artists in science art related to paleontology.

No rivers flow on the flat surface of the Yucatán Peninsula. When rains fall over the Yucatán, the water disappears into the thick limestone of the peninsula. Water flows through extensive cave systems beneath the surface, eventually making its way out to sea. For millennia humans living in the Yucatán gained access to fresh water through cenotes, massive sinkholes in the limestone. Without this access to water, the Maya civilization never would have existed, and any human habitation in the region would have been kept to a minimum. The massive subterranean labyrinth through which the life-giving fresh water currently flows was formed two to three million years ago during the Pleistocene and now comprises several thousands of miles of caves. During the times of worldwide glaciation and lower sea levels, many of these caves were void of water as they were above sea level. The present-day sea level was reached some 6,600 years ago at which time the caves remained permanently waterlogged with the fresh water seeping through the surface and moving out to sea. Finds within the past dozen years in these underwater caves appear to put human habitation in the Yucatán to before the deglaciation and sea-level rise to thousands of years before the rise of the Classic Maya civilization.

No rivers flow on the flat surface of the Yucatán Peninsula. When rains fall over the Yucatán, the water disappears into the thick limestone of the peninsula. Water flows through extensive cave systems beneath the surface, eventually making its way out to sea. For millennia humans living in the Yucatán gained access to fresh water through cenotes, massive sinkholes in the limestone. Without this access to water, the Maya civilization never would have existed, and any human habitation in the region would have been kept to a minimum. The massive subterranean labyrinth through which the life-giving fresh water currently flows was formed two to three million years ago during the Pleistocene and now comprises several thousands of miles of caves. During the times of worldwide glaciation and lower sea levels, many of these caves were void of water as they were above sea level. The present-day sea level was reached some 6,600 years ago at which time the caves remained permanently waterlogged with the fresh water seeping through the surface and moving out to sea. Finds within the past dozen years in these underwater caves appear to put human habitation in the Yucatán to before the deglaciation and sea-level rise to thousands of years before the rise of the Classic Maya civilization.

In the early 2000s a team led by Arturo González of the Museo del Desierto in Saltillo, Coahuila, explored several cave systems in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo in the northeastern third of the Yucatán Peninsula. The team explored a cave system called Naranjal, which extends almost 25 kilometers and has 8 entrances located near the Maya archaeological site of Tulum. The Naranjal system connects with another underwater cave system called Ox Bel Ha. González published his first findings in the year 2008. His 2008 report contained the data and extremely technical conclusions surrounding the discovery of two skeletons along with prehistoric hearths and the bones of extinct animals, mostly Ice Age megafauna. The Señora de las Palmas was one of the two intact skeletons discovered by researchers during the initial phases of González’s project. The other skeleton was found about 1 kilometer away from the señora and was nicknamed Eva de Naharon, after the Cave of Naharon, which is part of the northern section of the Naranjal underwater cavern system. Eva was a much younger woman, about 20 to 30 years old at the time of her death, but still considered to be quite mature for her time. The skeletons of both Eva and the more matronly señora were found articulated and intact, leading researchers to believe that the two women were given funerals and were buried in the cave before it slowly filled up with water many hundreds of years later. The Quintana Roo underwater cave database of human remains now contains 10 individuals, one of the best such study samples of prehistoric humans in the world. What are some of the conclusions of the scientists regarding these finds?

In the early 2000s a team led by Arturo González of the Museo del Desierto in Saltillo, Coahuila, explored several cave systems in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo in the northeastern third of the Yucatán Peninsula. The team explored a cave system called Naranjal, which extends almost 25 kilometers and has 8 entrances located near the Maya archaeological site of Tulum. The Naranjal system connects with another underwater cave system called Ox Bel Ha. González published his first findings in the year 2008. His 2008 report contained the data and extremely technical conclusions surrounding the discovery of two skeletons along with prehistoric hearths and the bones of extinct animals, mostly Ice Age megafauna. The Señora de las Palmas was one of the two intact skeletons discovered by researchers during the initial phases of González’s project. The other skeleton was found about 1 kilometer away from the señora and was nicknamed Eva de Naharon, after the Cave of Naharon, which is part of the northern section of the Naranjal underwater cavern system. Eva was a much younger woman, about 20 to 30 years old at the time of her death, but still considered to be quite mature for her time. The skeletons of both Eva and the more matronly señora were found articulated and intact, leading researchers to believe that the two women were given funerals and were buried in the cave before it slowly filled up with water many hundreds of years later. The Quintana Roo underwater cave database of human remains now contains 10 individuals, one of the best such study samples of prehistoric humans in the world. What are some of the conclusions of the scientists regarding these finds?

To date these bones researchers relied on a combination of scientific testing of the actual bones and correlating the findings with what was found alongside the bones, specifically, charcoal from pit fires and the bones of the prehistoric animals discovered. The fact that the bones had spent so much time underwater posed problems for traditional Carbon-14 testing to give an accurate date range for the individuals. González and his team had a hard time finding measurable organic components to the bones. A hearth existed near where the team found the bones of the Señora de las Palmas. The dates on the charcoal from the pit fire as received from the lab go back 9,000 years. Animal bones in the hearths and found throughout the cave system also help to set the context. Many of these animals started to become extinct some 12,000 years ago. Mexican archaeologist Carmen Rojas Sandoval working for the National Institute of Anthropology and History presented a paper in August of 2017 detailing her findings of the bones of ancient animals found in the cenotes and caves of the northeastern Yucatán Peninsula. She  showed that bones 23 different animals were found alongside those of the humans. These included those of extinct horses, camelids, giant bears, saber tooth tigers, peccaries and a giant armadillo, among others. Rojas even discovered a new species of giant sloth. To honor the local ancient Maya civilization, she gave the sloth the scientific name Xibalbaonyx oviceps, with “Xibalbá” referring to the ancient Maya underworld identified with the caves.

showed that bones 23 different animals were found alongside those of the humans. These included those of extinct horses, camelids, giant bears, saber tooth tigers, peccaries and a giant armadillo, among others. Rojas even discovered a new species of giant sloth. To honor the local ancient Maya civilization, she gave the sloth the scientific name Xibalbaonyx oviceps, with “Xibalbá” referring to the ancient Maya underworld identified with the caves.

The bones of the Señora de las Palmas and the others found in the underwater caves of the Yucatán may help re-write the history of the peopling of the Americas. Scientists are looking carefully at the cave finds and comparing them to the bones from similar finds throughout the hemisphere dating to the same time period. Human remains from the Ice Age and before have been found at a site in Brazil called Lagoa Santa and at Sabana de Bogotá in Colombia. In Mexico, some specimens dating to this time were also discovered outside of Mexico City. Due to many similarities among the specimens, scientists and are calling these people as a group, “Paleoamericans.” By examining the morphology, or the forms of the bones, one can see marked differences between these ancient Paleoamericans and modern-day Native American populations, such as the Maya, specifically in the shape of the head. The ancient and modern-day Maya, for example, have similar cranial structures to modern-day Native Americans found throughout the Americas and with populations in modern-day China and northern Asia. The skull morphology of the specimens found in the  Yucatán caves, of the so-called “Paleoamericans,” is more like that of modern-day Austro-melanesian groups. The Señora de las Palmas and her contemporaries seem to have more in common with people in southeast Asia than they do with modern-day Native Americans. These findings have led to the “Two Component Model” postulated by the Argentine paleoanthropologist Héctor Pucciarelli in the year 2004. According to Pucciarelli’s theory, the Americas were first colonized in two successive waves from Asia. The first one migrated through the Bering Passage from southeast Asia about 12,000 years ago. These Paleoamericans were also the ancestors of modern Austronesians. Austronesian people today are found in modern-day Indonesia and the southeast Asian mainland. According to this “Two Component Model,” the Paleoamericans were replaced by a second wave to come into the Americas 9,000 years ago. This second wave were the ancestors of modern-day Native Americans and the northern Asian groups. According to Pucciarelli, the replacement was exceedingly fast and occurred without any sort of genetic mixing of the two groups. Thus, according to the latest scientific theories, the people whose remains were discovered in the underwater cave systems were not related to the ancient Maya or to any modern-day inhabitants of the Yucatán.

Yucatán caves, of the so-called “Paleoamericans,” is more like that of modern-day Austro-melanesian groups. The Señora de las Palmas and her contemporaries seem to have more in common with people in southeast Asia than they do with modern-day Native Americans. These findings have led to the “Two Component Model” postulated by the Argentine paleoanthropologist Héctor Pucciarelli in the year 2004. According to Pucciarelli’s theory, the Americas were first colonized in two successive waves from Asia. The first one migrated through the Bering Passage from southeast Asia about 12,000 years ago. These Paleoamericans were also the ancestors of modern Austronesians. Austronesian people today are found in modern-day Indonesia and the southeast Asian mainland. According to this “Two Component Model,” the Paleoamericans were replaced by a second wave to come into the Americas 9,000 years ago. This second wave were the ancestors of modern-day Native Americans and the northern Asian groups. According to Pucciarelli, the replacement was exceedingly fast and occurred without any sort of genetic mixing of the two groups. Thus, according to the latest scientific theories, the people whose remains were discovered in the underwater cave systems were not related to the ancient Maya or to any modern-day inhabitants of the Yucatán.

Re-writing the history books on the peopling of the Americas has some challenges. Whenever new discoveries are made, no matter how thorough and well-documented they are, the pioneering researchers have the barriers of dogma and orthodoxy to break through. Those doing research on the Paleoamericans have to make their case to their peers and to the world at large. Many refuse  to accept new theories or alternative hypotheses, especially when lifetime careers are at stake. The researchers investigating the wealth of the underwater caves in the Yucatán are also racing against the clock to find new specimens. As the word got out about the Señora de las Palmas and the other skeletons, looters and vandals were quick to get to the caves. For example, in 2009 diver Harry Gust photographed and described human remains in a cave system accessed by the Chan Hol Cenote just 8 meters below the surface. When researchers returned to Chan Hol to the exact location of the intact human skeleton for further study, they had found the area vandalized with most of the bones, including the skull, missing. As there are thousands of cenotes throughout the Yucatán and many cave systems unknown or largely unexplored, it will be very difficult to protect potential finds from fossil hunters and souvenir seekers. It’s unknown at this point just how much has already been lost.

to accept new theories or alternative hypotheses, especially when lifetime careers are at stake. The researchers investigating the wealth of the underwater caves in the Yucatán are also racing against the clock to find new specimens. As the word got out about the Señora de las Palmas and the other skeletons, looters and vandals were quick to get to the caves. For example, in 2009 diver Harry Gust photographed and described human remains in a cave system accessed by the Chan Hol Cenote just 8 meters below the surface. When researchers returned to Chan Hol to the exact location of the intact human skeleton for further study, they had found the area vandalized with most of the bones, including the skull, missing. As there are thousands of cenotes throughout the Yucatán and many cave systems unknown or largely unexplored, it will be very difficult to protect potential finds from fossil hunters and souvenir seekers. It’s unknown at this point just how much has already been lost.

The story of the Señora de las Palmas continues to unfold, however. With more discoveries and keener scientific methods perhaps a clearer picture of the peoples of Ice Age Mexico will reveal itself sometime soon. For now, there is still a lot of speculation and many theories seeking to explain the mysteries discovered in these underwater caves of the Yucatán.

REFERENCES

Graf, Kelly E., Caroline V. Keltron and Michael R. Waters (eds.) Paleoamerican Odyssey. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2014. Buy the book here: https://amzn.to/2Z9v1nD