Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

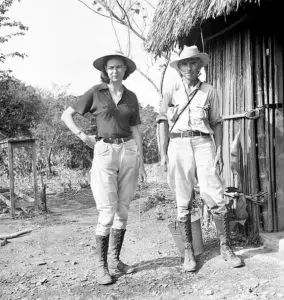

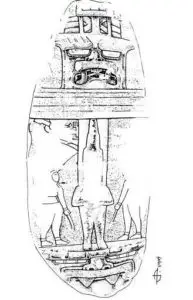

The date was January 16, 1939. American archaeologist Matthew Sterling was excited to be leading an in-depth expedition to a little-known ancient city called Tres Zapotes located in the Mexican state of Veracruz. This would be one of the 14 expeditions to different parts of the Americas led by Sterling, under of a joint venture between the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society. On that January day in 1939, Stirling and his team were exploring the many mounds along the Arroyo Hueyapan in the heart of Tres Zapotes. In front of one of the tallest mounds, next to an ancient altar, Sterling and his team discovered the lower half of a carved basalt monolith, or stela, that would be one of the most important finds of the American archaeologist’s career. Known as Stela C, this carved rock had an interesting image of a were-jaguar on one side, which was stylistically similar to what was being found at the time at major Olmec sites. This image has been interpreted by archaeologists to be a symbol of a powerful king who ruled the city. On another side of the stela Sterling noticed a series of bars and dots signifying a date that were familiar in the inscriptions of the Maya whose heartland was hundreds of miles to the east of the site. He copied down the writing and took it back to the base camp to show to his wife, Marion Sterling. Trained as an archaeologist in her own right and a constant companion of her husband on his many expeditions, Mrs. Sterling took to translating the date. As the top half of the stela was missing and so was part of one of the numbers indicating the time period called a baktun, Marion Sterling made an educated guess and came up with the date for Stela C. It read: September 3rd 32 BC. Thirty years later Mrs. Sterling’s judgment was validated when the top half of the stela was discovered, and the date was complete. The Sterling expedition had uncovered the earliest use of the Mesoamerican long-count calendar ever seen, only to be surpassed many decades later by Stela 2 at a small site called Chiapa de Corzo in the modern Mexican state of Chiapas, which has a confirmed date of December 6th 36 BC. At the time of the Stirling’s discovery of Stela C at Tres Zapotes, the Mesoamerican long-count dating system was previously thought to be the invention of the Maya, but this discovery in Veracruz re-wrote the history books, so to speak, and pushed its invention out of the Maya area and back in time. Under the Stirlings, the site of Tres Zapotes would yield many archaeological treasures, from hundreds of pieces of jade to thousands of fragments of pottery and sculpture to a few of the famous colossal Olmec stone heads as discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 80: https://mexicounexplained.com/olmec-colossal-stone-heads/. The multitude of artifacts came from Tres Zapotes’ long history of habitation, covering over 2,000 years. Some scholars believe that of all the cities of ancient Mexico it was the site that was occupied for the longest period of time. So, who lived at this place and what happened there?

The date was January 16, 1939. American archaeologist Matthew Sterling was excited to be leading an in-depth expedition to a little-known ancient city called Tres Zapotes located in the Mexican state of Veracruz. This would be one of the 14 expeditions to different parts of the Americas led by Sterling, under of a joint venture between the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society. On that January day in 1939, Stirling and his team were exploring the many mounds along the Arroyo Hueyapan in the heart of Tres Zapotes. In front of one of the tallest mounds, next to an ancient altar, Sterling and his team discovered the lower half of a carved basalt monolith, or stela, that would be one of the most important finds of the American archaeologist’s career. Known as Stela C, this carved rock had an interesting image of a were-jaguar on one side, which was stylistically similar to what was being found at the time at major Olmec sites. This image has been interpreted by archaeologists to be a symbol of a powerful king who ruled the city. On another side of the stela Sterling noticed a series of bars and dots signifying a date that were familiar in the inscriptions of the Maya whose heartland was hundreds of miles to the east of the site. He copied down the writing and took it back to the base camp to show to his wife, Marion Sterling. Trained as an archaeologist in her own right and a constant companion of her husband on his many expeditions, Mrs. Sterling took to translating the date. As the top half of the stela was missing and so was part of one of the numbers indicating the time period called a baktun, Marion Sterling made an educated guess and came up with the date for Stela C. It read: September 3rd 32 BC. Thirty years later Mrs. Sterling’s judgment was validated when the top half of the stela was discovered, and the date was complete. The Sterling expedition had uncovered the earliest use of the Mesoamerican long-count calendar ever seen, only to be surpassed many decades later by Stela 2 at a small site called Chiapa de Corzo in the modern Mexican state of Chiapas, which has a confirmed date of December 6th 36 BC. At the time of the Stirling’s discovery of Stela C at Tres Zapotes, the Mesoamerican long-count dating system was previously thought to be the invention of the Maya, but this discovery in Veracruz re-wrote the history books, so to speak, and pushed its invention out of the Maya area and back in time. Under the Stirlings, the site of Tres Zapotes would yield many archaeological treasures, from hundreds of pieces of jade to thousands of fragments of pottery and sculpture to a few of the famous colossal Olmec stone heads as discussed in Mexico Unexplained episode number 80: https://mexicounexplained.com/olmec-colossal-stone-heads/. The multitude of artifacts came from Tres Zapotes’ long history of habitation, covering over 2,000 years. Some scholars believe that of all the cities of ancient Mexico it was the site that was occupied for the longest period of time. So, who lived at this place and what happened there?

Located between the Tuxtla Mountains and the fertile delta of the Papaloapan River, the site of Tres Zapotes had immediate access to forested uplands and the swamps and streams of the broad Veracruz lowlands. The mountains nearby also provided resources, including stone for building and sculpture. The site had a fairly regular water source running through it, the Arroyo Hueyapan. The climate classification for Tres Zapotes is “tropical monsoon” with an average daily high temperature of almost 78 degrees, so the area has a year-round growing season. The location of the site was optimal for trade, and the archaeological record supports the notion that Tres Zapotes traded with many different cultures – from as far away as modern-day Guatemala – across the thousands of years it was occupied.

Located between the Tuxtla Mountains and the fertile delta of the Papaloapan River, the site of Tres Zapotes had immediate access to forested uplands and the swamps and streams of the broad Veracruz lowlands. The mountains nearby also provided resources, including stone for building and sculpture. The site had a fairly regular water source running through it, the Arroyo Hueyapan. The climate classification for Tres Zapotes is “tropical monsoon” with an average daily high temperature of almost 78 degrees, so the area has a year-round growing season. The location of the site was optimal for trade, and the archaeological record supports the notion that Tres Zapotes traded with many different cultures – from as far away as modern-day Guatemala – across the thousands of years it was occupied.

Archaeologists believe that Tres Zapotes was founded by the Olmecs around 1500 BC. It emerged as a center of power in the far western part of the Olmec homeland at around 900 BC during what scholars call the Middle Formative Period. The first monumental buildings appeared at Tres Zapotes around 500 BC. The rise of this site began around the same time as the decline of the other major Olmec centers to the east, notably the cities of San Lorenzo and La Venta. It is unknown whether Tres Zapotes took on refugees from these failing cities or if it just existed on its own and simply continued the Olmec traditions while the other sites collapsed. Archaeologists consider Tres Zapotes to be one of the “capitals” of the Olmecs, although the Olmec civilization appears to be somewhat like the Maya and little like the Aztec in that each city functioned as a separate political entity. There is even evidence at Tres Zapotes that the city was split among ruling families or other political factions. This theory becomes clearer during what scholars call the Epi-Olmec period, which seems to have been the heyday of the city of Tres Zapotes.

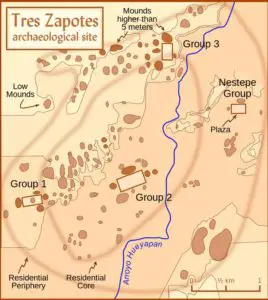

With the other Olmec centers of power gone by about 400 BC, Tres Zapotes became the major political presence in what was then the traditional Olmec homeland. Over time the culture slightly changed, and this is why scholars have classified this period as something new, the Epi-Olmec. In Tres Zapotes and the surrounding region elements of culture under this new tradition became more advanced and other parts lacked the sophistication of the older Olmec civilization. The advanced art and architecture of the Olmecs seemed a bit cruder during this Epi-Olmec era. This time, though, saw the flowering of the calendar system and Mesoamerica’s first writing system. Although unrefined compared to the later writing systems of ancient Mexico, a basic hieroglyphic script called Isthmian or Epi-Olmec got its start in Tres Zapotes and the surrounding area. Very few examples of this unique writing style exist on various monuments and artifacts, but it is clear that it served as the foundation for the Maya writing system used extensively a few centuries later. For more information about the Maya writing system, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 16 https://mexicounexplained.com/writing-ancient-maya-history-words/ . It was during the Epi-Olmec period from about 400 BC to around 200 AD when most of the 160 mounds and platforms were built at Tres Zapotes. The site has 4 mound groups, referred to as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3 and the Nestepe Group. The mound groups consisted mostly of royal residences and small temples. Group 2 is the largest such grouping and is located more of less in the center of the site. The other mound groups are located about 1 mile from Group 2 and from each other. Researchers have concluded that this clustering meant that during the Epi-Olmec phase Tres Zapotes was most likely fractured politically with 4 independent royal families ruling over the city and designated portions of the surrounding areas in a decentralized fashion. During the Epi-Olmec period, the archaeological record shows very few artifacts coming from outside the region, indicating that long-distant trade was rare or possibly non-existent. As mentioned earlier, monuments and most every other type of art, including functional pottery, lacked the fine artistic style for which the Olmecs of the immediate past were known. Some claim that the basalt used in some of the larger carvings was of an inferior quality and thus harder to work with, while others claim that the lack of attention to the finer things indicated a harsher and more austere existence at Tres Zapotes during the Epi-Olmec times.

With the other Olmec centers of power gone by about 400 BC, Tres Zapotes became the major political presence in what was then the traditional Olmec homeland. Over time the culture slightly changed, and this is why scholars have classified this period as something new, the Epi-Olmec. In Tres Zapotes and the surrounding region elements of culture under this new tradition became more advanced and other parts lacked the sophistication of the older Olmec civilization. The advanced art and architecture of the Olmecs seemed a bit cruder during this Epi-Olmec era. This time, though, saw the flowering of the calendar system and Mesoamerica’s first writing system. Although unrefined compared to the later writing systems of ancient Mexico, a basic hieroglyphic script called Isthmian or Epi-Olmec got its start in Tres Zapotes and the surrounding area. Very few examples of this unique writing style exist on various monuments and artifacts, but it is clear that it served as the foundation for the Maya writing system used extensively a few centuries later. For more information about the Maya writing system, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 16 https://mexicounexplained.com/writing-ancient-maya-history-words/ . It was during the Epi-Olmec period from about 400 BC to around 200 AD when most of the 160 mounds and platforms were built at Tres Zapotes. The site has 4 mound groups, referred to as Group 1, Group 2, Group 3 and the Nestepe Group. The mound groups consisted mostly of royal residences and small temples. Group 2 is the largest such grouping and is located more of less in the center of the site. The other mound groups are located about 1 mile from Group 2 and from each other. Researchers have concluded that this clustering meant that during the Epi-Olmec phase Tres Zapotes was most likely fractured politically with 4 independent royal families ruling over the city and designated portions of the surrounding areas in a decentralized fashion. During the Epi-Olmec period, the archaeological record shows very few artifacts coming from outside the region, indicating that long-distant trade was rare or possibly non-existent. As mentioned earlier, monuments and most every other type of art, including functional pottery, lacked the fine artistic style for which the Olmecs of the immediate past were known. Some claim that the basalt used in some of the larger carvings was of an inferior quality and thus harder to work with, while others claim that the lack of attention to the finer things indicated a harsher and more austere existence at Tres Zapotes during the Epi-Olmec times.

Tres Zapotes moved into the Mesoamerican Classic era and although the site had not yet been abandoned, archaeologists have noted another shift in cultures. Around 100 to 200 AD things began to change in the region once again. While during the Olmec times Tres Zapotes had been in the far western part of the Olmec civilization’s homeland, by the early centuries AD it had become part of the southern edge of a somewhat different culture referred to in the literature as the Classic Veracruz Culture or the Gulf Coast Classic Culture. Other cities to the north rose in prominence at this time but Tres Zapotes held its own. There was an increase in building at the site that coincided with a resumption of long-distance trade with other cultures. Throughout the Classic Veracruz Culture there was more social hierarchy than the previous Epi-Olmec culture and wealth was more concentrated in the hands of a few elites. Power became more centralized, much as it had been in the Olmec civilization some 2,000 years earlier. We see an increase in craft specialization at this time, the importing of luxury goods from a thousand miles away, and a more formalized and intense religious structure. Perhaps as a means of social control and to legitimize the status of the elites, there was more of a focus on religious ritual at Tres Zapotes during the Classic Veracruz, including an increase in ceremonies involving human sacrifice. The Mesoamerican ballgame became very popular at this time as well, thus following a historical theme of the importance of sports during times of social inequality. For more information about the Mesoamerican ballgame, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 53. Art during this period in the history of Tres Zapotes became more refined and distinct. In the early centuries AD we find the curious wheeled animal figurines, and statues with smiling triangular features which the later Totonac civilization would copy and refine. In some of the art and artifacts of the Classic Veracruz, researchers have noted a distinctive scrolling pattern that may have been part of a pictographic written language, whose meaning is not understood today. Classic Veracruz culture existed at the same time as the Classic Maya and also coexisted with the height of the city of Teotihuacan in the central highlands of Mexico. The archaeological record at Tres Zapotes shows influence from these distant cultures most likely the result of the increased long-distance trade discussed earlier.

Tres Zapotes moved into the Mesoamerican Classic era and although the site had not yet been abandoned, archaeologists have noted another shift in cultures. Around 100 to 200 AD things began to change in the region once again. While during the Olmec times Tres Zapotes had been in the far western part of the Olmec civilization’s homeland, by the early centuries AD it had become part of the southern edge of a somewhat different culture referred to in the literature as the Classic Veracruz Culture or the Gulf Coast Classic Culture. Other cities to the north rose in prominence at this time but Tres Zapotes held its own. There was an increase in building at the site that coincided with a resumption of long-distance trade with other cultures. Throughout the Classic Veracruz Culture there was more social hierarchy than the previous Epi-Olmec culture and wealth was more concentrated in the hands of a few elites. Power became more centralized, much as it had been in the Olmec civilization some 2,000 years earlier. We see an increase in craft specialization at this time, the importing of luxury goods from a thousand miles away, and a more formalized and intense religious structure. Perhaps as a means of social control and to legitimize the status of the elites, there was more of a focus on religious ritual at Tres Zapotes during the Classic Veracruz, including an increase in ceremonies involving human sacrifice. The Mesoamerican ballgame became very popular at this time as well, thus following a historical theme of the importance of sports during times of social inequality. For more information about the Mesoamerican ballgame, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 53. Art during this period in the history of Tres Zapotes became more refined and distinct. In the early centuries AD we find the curious wheeled animal figurines, and statues with smiling triangular features which the later Totonac civilization would copy and refine. In some of the art and artifacts of the Classic Veracruz, researchers have noted a distinctive scrolling pattern that may have been part of a pictographic written language, whose meaning is not understood today. Classic Veracruz culture existed at the same time as the Classic Maya and also coexisted with the height of the city of Teotihuacan in the central highlands of Mexico. The archaeological record at Tres Zapotes shows influence from these distant cultures most likely the result of the increased long-distance trade discussed earlier.

Ironically, a few centuries after the fall of Teotihuacan and around the time of the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization, the city of Tres Zapotes lost its place in the sun. By about 900 AD the city was all but abandoned with some squatters hanging on through the ensuing centuries. The 2,000+ year run of Tres Zapotes has ended. As it was one of the longest-lasting inhabited cities in ancient Mexico, there is still much to learn from this site and discoveries are made here with each new dig permitted by the Mexican government. With such a long and intense history Tres Zapotes still has many stories yet to tell.

REFERENCES

Coe, Michael D., et al. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership Princeton, NJ: Harry Abrams, 1996. We are Amazon affiliates. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/32OMDcI

Diehl, Richard A. The Olmecs: America’s First Civilization. London: Thames & Hudson, 2004. We are Amazon affiliates. Get the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3dO8o2Q