Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

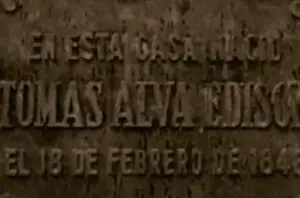

On a humble home located at 19 Calle Hidalgo in the town of Sombrerete, in the western part of the Mexican state of Zacatecas for many years there was a bronze plaque which read, translated into English:

On a humble home located at 19 Calle Hidalgo in the town of Sombrerete, in the western part of the Mexican state of Zacatecas for many years there was a bronze plaque which read, translated into English:

“Tomás Alva Edison was born in this house on February 18, 1848.”

The American Thomas Edison – known for creating such technological marvels as the light bulb, the phonograph and the motion picture camera – held over 1,000 patents and is considered to be one of the most important and prolific inventors in the history of the world. The history books state that the inventor, whose full name was Thomas Alva Edison, was born in Milan, Ohio on February 11, 1847 and moved to Michigan when he was either 6 or 7. According to the same accepted historical sources, Edison’s father – Samuel Edison – was from Canada, born in Nova Scotia, and his mother – Nancy Elliott – hailed from rural New York State. Thomas’ father, Samuel, was supposedly involved in a plot to overthrow the government of Canada and escaped to the United States sometime in the 1830s. The family name, “Edison,” was once “Edeson” and is of Dutch origin. Although it was customary at the time for a boy to get his mother’s maiden name as his middle name, Edison’s middle name was Alva, which was a common first name for boys in mid-19th Century America. Edison’s early life is full of many inconsistencies and over the years there has been much speculation about the inventor’s true origins and the activities of his father in the decades before the inventor’s birth. Thomas Edison never had an American birth certificate for researchers to examine, which was not all that uncommon in the young United States of the 1840s. Even when Thomas Edison was alive there were rumors and even articles appearing in the Mexican press claiming that America’s most famous inventor was not born in America at all. In this episode we will explore the possible evidence of Edison’s origins in Mexico and his deep family history in that country. It’s important to note here part of Anthony Taylor’s introduction to every episode of Mexico Unexplained: “This series presents information based partly on theory and conjecture. The podcaster’s purpose it to suggest some possible explanations but not necessarily the only ones to the subjects we will examine.”

According to verifiable sources, in the 1840s, the decade Thomas Alva Edison was born, there were three families with combinations of the surname “Alva” in Sombrerete, Zacatecas. “Alva” is sometimes spelled with a “b” instead of a “v” and is a common Hispanic last name even to this day. The Alva families found in the records of Sombrerete, Zacatecas, in the first half of the 1800s were the Alva-Arias, Alva-Santini, and Alva-Edison families. Listed in church records was a man named Samuel Alva married to a woman named Nancy Edison, an American or Englishwoman. They had a son named Tomás. There are records that Tomás Alva went to school in Sombrerete and many students and a few teachers remembered him. In an 1899 interview with a Durango newspaper called El Sol, former elementary school teacher José Guadalupe Ponce told reporters that he had Thomas Edison as a student in his class in Sombrerete some 40 years hence, but his name then was Tomás Alva. The Alva-Edison family was not originally from Zacatecas, according to local records. Tomás’ father Samuel was a mining engineer who came from a small town located northeast of Mexico City in the state of México called San Martín de las Pirámides. The town is so named because it is a stone’s throw from the archaeological site of Teotihuacán. The Alva family has lived in the town of San Martín de las Pirámides and the neighboring pueblito of Santa María Palapa for centuries. In fact, in some documents, Tomás’ father’s name is listed as Samuel Alva Ixtlixóchitl. The last name Ixtlixóchitl can be traced to the minor nobility of the Kingdom of Texcoco long before the Spanish arrived in the Basin of Mexico. Texcoco was absorbed into the Aztec Empire in the 1400s and its noble house was allowed to continue its local rule. Even after the Spanish Conquest the members of the Texcoco nobility were able to keep their Nahuatl surnames, such as Ixtlixóchitl. For an interesting aside on the noble families of Texcoco please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 133. https://mexicounexplained.com//the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/

According to verifiable sources, in the 1840s, the decade Thomas Alva Edison was born, there were three families with combinations of the surname “Alva” in Sombrerete, Zacatecas. “Alva” is sometimes spelled with a “b” instead of a “v” and is a common Hispanic last name even to this day. The Alva families found in the records of Sombrerete, Zacatecas, in the first half of the 1800s were the Alva-Arias, Alva-Santini, and Alva-Edison families. Listed in church records was a man named Samuel Alva married to a woman named Nancy Edison, an American or Englishwoman. They had a son named Tomás. There are records that Tomás Alva went to school in Sombrerete and many students and a few teachers remembered him. In an 1899 interview with a Durango newspaper called El Sol, former elementary school teacher José Guadalupe Ponce told reporters that he had Thomas Edison as a student in his class in Sombrerete some 40 years hence, but his name then was Tomás Alva. The Alva-Edison family was not originally from Zacatecas, according to local records. Tomás’ father Samuel was a mining engineer who came from a small town located northeast of Mexico City in the state of México called San Martín de las Pirámides. The town is so named because it is a stone’s throw from the archaeological site of Teotihuacán. The Alva family has lived in the town of San Martín de las Pirámides and the neighboring pueblito of Santa María Palapa for centuries. In fact, in some documents, Tomás’ father’s name is listed as Samuel Alva Ixtlixóchitl. The last name Ixtlixóchitl can be traced to the minor nobility of the Kingdom of Texcoco long before the Spanish arrived in the Basin of Mexico. Texcoco was absorbed into the Aztec Empire in the 1400s and its noble house was allowed to continue its local rule. Even after the Spanish Conquest the members of the Texcoco nobility were able to keep their Nahuatl surnames, such as Ixtlixóchitl. For an interesting aside on the noble families of Texcoco please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 133. https://mexicounexplained.com//the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/

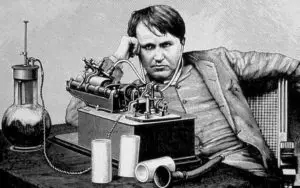

According to the legend, rumor, conspiracy theory or however one wants to label this alternative history, the young Tomás Alva immigrated to the United States either with or without his parents when he was between the ages of 12 and 20. It was well accepted during his lifetime that Thomas Edison suffered from partial hearing loss and that was the reason for his occasional mispronunciation of words and unusual way of speaking. The hearing loss supposedly occurred when Edison was a boy, when he was throttled by the ears by an angry train conductor. Those who subscribe to the alternative history of Edison claim that this story was a cover for the fact that English was not the famous inventor’s first language. A curious piece of trivia about Thomas Edison is that he did indeed speak fluent Spanish. When one of Edison’s assistants overheard him speaking Spanish one day and asked him about it, Edison replied that he learned the language in preparation for a conference in Brazil that he wound up never attending. An interesting thing to note is that the language spoken in Brazil is Portuguese and not Spanish and Edison probably made up the story on the fly so as to quell the curiosity of the assistant.

According to the legend, rumor, conspiracy theory or however one wants to label this alternative history, the young Tomás Alva immigrated to the United States either with or without his parents when he was between the ages of 12 and 20. It was well accepted during his lifetime that Thomas Edison suffered from partial hearing loss and that was the reason for his occasional mispronunciation of words and unusual way of speaking. The hearing loss supposedly occurred when Edison was a boy, when he was throttled by the ears by an angry train conductor. Those who subscribe to the alternative history of Edison claim that this story was a cover for the fact that English was not the famous inventor’s first language. A curious piece of trivia about Thomas Edison is that he did indeed speak fluent Spanish. When one of Edison’s assistants overheard him speaking Spanish one day and asked him about it, Edison replied that he learned the language in preparation for a conference in Brazil that he wound up never attending. An interesting thing to note is that the language spoken in Brazil is Portuguese and not Spanish and Edison probably made up the story on the fly so as to quell the curiosity of the assistant.

Before formal state-issued birth certificates were common in Mexico, church records were used as quasi-official documents and recorded births, baptisms, marriages and deaths. In Mexico, at the time of Thomas Edison’s birth in the 1840s, birth records would have been kept at the local parish. In 1859, under the presidency of Benito Juárez, one of the Reform Laws was to create the Civil State Tribunals. These tribunals would use the church records to make formal legal documents, recording births especially, so that indigenous people could exercise their rights in court. At the time of Edison’s rise to fame in the 1870s and 1880s, townsfolk in Sombrerete, Zacatecas claimed to have seen the church and civil records that indicated the birth of a Tomás Alva in Sombrerete. This was the basis for putting the plaque on the house on Hidalgo Street mentioned earlier. Unfortunately, the hall of records for the town of Sombrerete was burned to the ground in May of 1911 during the Mexican Revolution and the local parish was also ransacked. Regrettably, no birth records survive in the town of Sombrerete before the onset of the Revolution.

In the 1930s letters surfaced in San Martín de las Pirámides – the birthplace of Tomás Alva’s father Samuel – reportedly from the American inventor dating to 1926 or 1927. Thomas Edison would have been 80 years old at the time the letters were written and just a few years away from his death in 1931. Now in the National Archives in Mexico City and not available to the public for examination, the letters are reportedly written in Spanish by Thomas Edison himself. Apparently, Edison was trying to track down distant relatives in San Martín de las Pirámides and the nearby village of Santa María Palapa. Why the letters are off limits to researchers is anyone’s guess, but news of the letters did catch the attention of the curious in the years immediately after Edison’s death. In the mid-1940s an American research team went to Mexico to investigate the rumors of Edison’s Mexican heritage. With the records at Sombrerete, Zacatecas gone, the researchers went to San Martín de las Pirámides and visited the town church. If they could not find the actual birth records of Thomas Alva Edison perhaps they could find birth or marriage records for his parents or even other clues about the Alva or Ixtlixóchitl families that would tie them to the famous inventor. After weeks of investigating, the American team returned to the United States and said they could find no evidence that Edison was Mexican. America would have its brilliant mythical hero for its civic pantheon.

In the 1930s letters surfaced in San Martín de las Pirámides – the birthplace of Tomás Alva’s father Samuel – reportedly from the American inventor dating to 1926 or 1927. Thomas Edison would have been 80 years old at the time the letters were written and just a few years away from his death in 1931. Now in the National Archives in Mexico City and not available to the public for examination, the letters are reportedly written in Spanish by Thomas Edison himself. Apparently, Edison was trying to track down distant relatives in San Martín de las Pirámides and the nearby village of Santa María Palapa. Why the letters are off limits to researchers is anyone’s guess, but news of the letters did catch the attention of the curious in the years immediately after Edison’s death. In the mid-1940s an American research team went to Mexico to investigate the rumors of Edison’s Mexican heritage. With the records at Sombrerete, Zacatecas gone, the researchers went to San Martín de las Pirámides and visited the town church. If they could not find the actual birth records of Thomas Alva Edison perhaps they could find birth or marriage records for his parents or even other clues about the Alva or Ixtlixóchitl families that would tie them to the famous inventor. After weeks of investigating, the American team returned to the United States and said they could find no evidence that Edison was Mexican. America would have its brilliant mythical hero for its civic pantheon.

A group of Mexican researchers did not trust the findings of the Americans, so they retraced the steps of the team’s research, starting at the small parish in San Martín de las Pirámides. They found something quite curious in the ecclesiastical records, which amounted to a big old book with all the dates of births, baptisms, marriages and deaths of the town going back a good century and a half. The pages that would have documented the Alva family in San Martín were torn out. The priest in charge of the office matters of the church could not offer any explanation as to why these were the only pages missing in this massive book of records. Did the pages intentionally disappear to cover up an unwanted truth, or was it mere coincidence that these were the only pages missing? If this was part of a cover-up to erase Thomas Edison’s real identity, why? Are there more reasons for this that go beyond simple national pride? Is the whole story just a fanciful tall tale based on the wishful thinking of a handful of Mexicans? You decide.

REFERENCES

De la Pena Gil, Adolfo. “Edison nacio en Mexico.” In El Teosofo, Oct. 1956, pp. 49-54. (in Spanish)

El Sol newspaper archives.

“Mito o Realidad” blog, 4 May 2012.