Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In 1887, a year after the organization’s founding, the American Kennel Club had an interesting dog on its registry of purebreds. The dog’s name was “Mee Too” and its listed breed was “Mexican Hairless.” Americans paid little attention to this type of dog until October 19, 1940 when a Mexican Hairless dog named “Chinito Junior” became an American Kennel Club champion. The owner of the 1940 champion dog, an eccentric New York socialite named Valetska Radtke, must have wowed the AKC with her unusual canine, but the interest in this breed in the United States was either short-lived or nonexistent. By 1959 the American Kennel Club dropped the “Mexican Hairless” breed from its stud book because officials thought the dog to be extinct or at least too rare to be of any consequence. While not entirely accurate, there was some truth to the idea of the scarcity of the Mexican Hairless, known for centuries in Mexico as the xoloitzcuintli. From Spanish Colonial times to the early 20th Century the dog became more difficult to find and only existed in remote areas in purebred form. Dating back well over 3,000 years, the xoloitzcuintli, or xolo for short, had interbred with a wide variety of European dogs over the years and many believed that this iconic Mexican animal would not last through the 20th Century. Mexican painter Diego Rivera was a huge advocate of the xolo and realized the importance of keeping this symbol of Mexico alive. Rivera went beyond just making the wider public aware of the dog through his paintings. In 1925 he started the first kennel to breed xolos, hand-picking the finest examples he could find to breed and thus continue the ancient bloodlines. The trajectory of this breed altered in the mid-1950s. Between 1954 and 1956, a small band of dog lovers vowed to rescue the xolo from the brink of extinction. Headed by British Chihuahua expert Norman Pelham Wright and underwritten by a European countess, the Xoloitzcuintli Expedition went to the Rio Balsas area of the Mexican state of Guerrero to collect specimens of the dogs. With ten canines they began a serious breeding program. To reestablish xolos as a recognized breed with the American Kennel Club, the Xoloitzcuintli Club of America organized itself in 1986. By January 2011, The xolo was fully reinstated into the AKC and became eligible for competition in the Non-Sporting Group. There are currently some 30,000 xoloitzcuintlis in the United States and the unusual canine is now recognized as the national dog of Mexico.

In 1887, a year after the organization’s founding, the American Kennel Club had an interesting dog on its registry of purebreds. The dog’s name was “Mee Too” and its listed breed was “Mexican Hairless.” Americans paid little attention to this type of dog until October 19, 1940 when a Mexican Hairless dog named “Chinito Junior” became an American Kennel Club champion. The owner of the 1940 champion dog, an eccentric New York socialite named Valetska Radtke, must have wowed the AKC with her unusual canine, but the interest in this breed in the United States was either short-lived or nonexistent. By 1959 the American Kennel Club dropped the “Mexican Hairless” breed from its stud book because officials thought the dog to be extinct or at least too rare to be of any consequence. While not entirely accurate, there was some truth to the idea of the scarcity of the Mexican Hairless, known for centuries in Mexico as the xoloitzcuintli. From Spanish Colonial times to the early 20th Century the dog became more difficult to find and only existed in remote areas in purebred form. Dating back well over 3,000 years, the xoloitzcuintli, or xolo for short, had interbred with a wide variety of European dogs over the years and many believed that this iconic Mexican animal would not last through the 20th Century. Mexican painter Diego Rivera was a huge advocate of the xolo and realized the importance of keeping this symbol of Mexico alive. Rivera went beyond just making the wider public aware of the dog through his paintings. In 1925 he started the first kennel to breed xolos, hand-picking the finest examples he could find to breed and thus continue the ancient bloodlines. The trajectory of this breed altered in the mid-1950s. Between 1954 and 1956, a small band of dog lovers vowed to rescue the xolo from the brink of extinction. Headed by British Chihuahua expert Norman Pelham Wright and underwritten by a European countess, the Xoloitzcuintli Expedition went to the Rio Balsas area of the Mexican state of Guerrero to collect specimens of the dogs. With ten canines they began a serious breeding program. To reestablish xolos as a recognized breed with the American Kennel Club, the Xoloitzcuintli Club of America organized itself in 1986. By January 2011, The xolo was fully reinstated into the AKC and became eligible for competition in the Non-Sporting Group. There are currently some 30,000 xoloitzcuintlis in the United States and the unusual canine is now recognized as the national dog of Mexico.

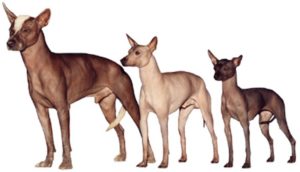

Not all xolos are hairless. The ones classified as “hairless” often have whisker-like hairs growing on their heads, paws or tails, but are generally smooth. The non-hairless Xoloitzcuintlis look as sleek as their hairless counterparts and come with a shiny, close-fitting and short coat. The hairless and the furred varieties can come from the same litter. The skin of the hairless xolo is more like a hide and requires maintenance with oils and lotions to keep it moist and to safeguard the dog from the sun. The colors of the dogs range from light brown to black, and the hairless variety gets darker with more sun exposure. Their bodies are usually lean and muscular, and their ears are like a bat’s and stick up. Xolos have long necks and almond-shaped eyes. The hairless variety usually has bad teeth. Xolos can range in weight from 10 to 50 pounds. Like the poodle, xoloitzuintlis come in three sizes: Standard, miniature and toy. The standard measures between 18 inches to 23 inches at the shoulder while the miniature measures 14 inches to 18 inches tall. The smaller toy variety measures only 10 inches to 14 inches at the shoulder. The dogs are said to have a primitive temperament because they have not been bred over the years to have docile qualities. They are alert, intelligent, have high energy, and also have keen hunting and social instincts. Although they get along great with other dogs, xolos may be very wary of unfamiliar humans and need to be socialized early if the dog owner has children in the family. They are also very clean and sometimes groom themselves like cats. Even the xolos with fur have a hard time tolerating cold weather. The xolo may also experience a great deal of sensitivity to loud noises.

Not all xolos are hairless. The ones classified as “hairless” often have whisker-like hairs growing on their heads, paws or tails, but are generally smooth. The non-hairless Xoloitzcuintlis look as sleek as their hairless counterparts and come with a shiny, close-fitting and short coat. The hairless and the furred varieties can come from the same litter. The skin of the hairless xolo is more like a hide and requires maintenance with oils and lotions to keep it moist and to safeguard the dog from the sun. The colors of the dogs range from light brown to black, and the hairless variety gets darker with more sun exposure. Their bodies are usually lean and muscular, and their ears are like a bat’s and stick up. Xolos have long necks and almond-shaped eyes. The hairless variety usually has bad teeth. Xolos can range in weight from 10 to 50 pounds. Like the poodle, xoloitzuintlis come in three sizes: Standard, miniature and toy. The standard measures between 18 inches to 23 inches at the shoulder while the miniature measures 14 inches to 18 inches tall. The smaller toy variety measures only 10 inches to 14 inches at the shoulder. The dogs are said to have a primitive temperament because they have not been bred over the years to have docile qualities. They are alert, intelligent, have high energy, and also have keen hunting and social instincts. Although they get along great with other dogs, xolos may be very wary of unfamiliar humans and need to be socialized early if the dog owner has children in the family. They are also very clean and sometimes groom themselves like cats. Even the xolos with fur have a hard time tolerating cold weather. The xolo may also experience a great deal of sensitivity to loud noises.

One of the most curious things about this dog breed might be its name. It has three different spellings and the word “xoloitzcuintli” is often shortened to “xolo” by non-Mexicans and Mexicans alike for ease of pronunciation. The word is from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire which still has over a million speakers today. Xoloitzcuintli is a combination of two words, “Xolotl” and “itzcuintle.” “Itzcuintle” means “dog” in English and Xolotl was an Aztec god. It’s important to look at the god Xolotl and what role the xoloitzcuintli played in ancient Mexican myths and legends.

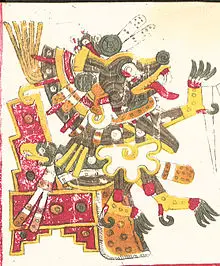

Archaeologists have long discovered dog remains in burials from commoners to the elites throughout ancient Mexico. Xolo bones have even been found underneath the Templo Mayor or main temple in the former Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, now the center of modern Mexico City. The ancients saw the xolos as a bridge from this life to the next. In many cases on the death of a family member, the survivors would sacrifice a dog that was close to the deceased and bury it along with him or her. The loyal dog of the earthly life would help its master travel to the afterlife, the Aztec underworld called Mictlan. The god Xolotl is the main guide of all things to and through Mictlan, including the sun whom he accompanies every day in a ceremonial daily “death.” The god Xolotl is often represented as a dog-headed man, or a skeleton. Sometimes ancient artists portrayed him as a hideous monster with feet going backwards. Xolotl usually does not have eyes in his many artistic depictions. As the legends go, when a group of old gods sacrificed themselves to create a new world – the present world we are now in – the dog-headed Xolotl wept so much that he literally cried his eyes out. When crossing over to Mictlan, the newly dead must ford a very deep river. The dogs, along with Xolotl himself, help people navigate this dangerous waterway to cross over to their new lives. In the ancient Aztec belief system, the spirits of the dogs are recycled. According to the legends the xoloitzcuintlis with patchy hair – the ones prone to win “ugly dog” competitions nowadays – are the dogs that have been reincarnated many times and have made the journey to the underworld often. The elites thus desired the patchy-haired dogs more than the sleek and completely hairless ones because these dogs had more experience with all things afterlife.

Archaeologists have long discovered dog remains in burials from commoners to the elites throughout ancient Mexico. Xolo bones have even been found underneath the Templo Mayor or main temple in the former Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, now the center of modern Mexico City. The ancients saw the xolos as a bridge from this life to the next. In many cases on the death of a family member, the survivors would sacrifice a dog that was close to the deceased and bury it along with him or her. The loyal dog of the earthly life would help its master travel to the afterlife, the Aztec underworld called Mictlan. The god Xolotl is the main guide of all things to and through Mictlan, including the sun whom he accompanies every day in a ceremonial daily “death.” The god Xolotl is often represented as a dog-headed man, or a skeleton. Sometimes ancient artists portrayed him as a hideous monster with feet going backwards. Xolotl usually does not have eyes in his many artistic depictions. As the legends go, when a group of old gods sacrificed themselves to create a new world – the present world we are now in – the dog-headed Xolotl wept so much that he literally cried his eyes out. When crossing over to Mictlan, the newly dead must ford a very deep river. The dogs, along with Xolotl himself, help people navigate this dangerous waterway to cross over to their new lives. In the ancient Aztec belief system, the spirits of the dogs are recycled. According to the legends the xoloitzcuintlis with patchy hair – the ones prone to win “ugly dog” competitions nowadays – are the dogs that have been reincarnated many times and have made the journey to the underworld often. The elites thus desired the patchy-haired dogs more than the sleek and completely hairless ones because these dogs had more experience with all things afterlife.

The Aztecs were not the only culture in ancient Mexico to revere the Xoloitzcuintli. The Toltecs and the Maya and assorted smaller cultures in central Mexico also held the dog in high regard. Since the Maya had a written language, we can see a dog god like Xolotl existing a thousand years before the hieght of the Aztec Empire. In a famous bark paper book called The Dresden Codex, ancient Maya artists depicted a dog god carrying a lightning bolt and it is associated with death. He comes down from the shadows and shepherds souls to the next life, much like the Aztec god. In the Maya myths, the dog god is also responsible for giving fire to mankind, a sort of canine version of Prometheus. Sometimes the dog god is referred to as “Lightening Beast” in Classic Maya inscriptions.

Beyond the meaning ascribed to xolos in myths and legends, the dogs served many practical and even some magical purposes in the daily lives of the people of ancient Mexico. Much of what we know about the role of xoloitzcuintlis in the lives of the ancient Mesoamerican peoples comes from early Spanish accounts during colonial days immediately after the conquest. Spanish chroniclers described the multiple uses of these dogs. Besides the usual garbage disposal and alarm roles that dogs still play in all Latin American countries to this day, xolos were companions and used to hunt wild turkeys and deer. They were also a food source. Conquistador Hernán Cortés himself even described a lavish Aztec banquet in which young xoloitzcuintli meat was a prized delicacy. The dog also had medicinal and mystical properties. Because of its high body temperature, xolos were used as a sort of hot water bottle for the sick. The dogs were also believed to ease the pain of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. On cold nights in the Mexican highlands, dogs usually slept with humans to keep the family warm.

Beyond the meaning ascribed to xolos in myths and legends, the dogs served many practical and even some magical purposes in the daily lives of the people of ancient Mexico. Much of what we know about the role of xoloitzcuintlis in the lives of the ancient Mesoamerican peoples comes from early Spanish accounts during colonial days immediately after the conquest. Spanish chroniclers described the multiple uses of these dogs. Besides the usual garbage disposal and alarm roles that dogs still play in all Latin American countries to this day, xolos were companions and used to hunt wild turkeys and deer. They were also a food source. Conquistador Hernán Cortés himself even described a lavish Aztec banquet in which young xoloitzcuintli meat was a prized delicacy. The dog also had medicinal and mystical properties. Because of its high body temperature, xolos were used as a sort of hot water bottle for the sick. The dogs were also believed to ease the pain of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. On cold nights in the Mexican highlands, dogs usually slept with humans to keep the family warm.

Some researchers who are more on the “fringe” have likened the dog representations of the ancient Mexican god Xolotl to the jackal-headed god Anubis of ancient Egypt. Does a similarity in canine gods suggest an ancient Mexico ancient Egypt connection? The head of the god Anubis looks eerily like a xoloitzcuitli with its tall, bat-like ears, thin neck and longer snout. Some artistic representations of the gods Xolotl and Anubis are very hard to tell apart from one another. Like the Aztec god Xolotl, Anubis also served as a guide for souls to the underworld. In addition, Anubis judged a person at the time of death to see if he or she was worthy to make the journey. The god is also associated with embalming and cemeteries. Critics are quick to point out that canines have been companions to humans for millennia and the fact that dogs accompany people as guides to the underworld in two cultures which supposedly had no contact with each other is just a coincidence. To those who want to believe, of course, there are no such things as coincidences or chance happenings. Some believe that these dog-god myths originated in the New World and were transported to ancient Egypt  thousands of years ago. For more information about ancient Mexico as the mother civilization of the Old World, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 110, “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-continent-mu-mexican-mother-civilization/ Some similarities aside, notable differences exist between Xolotl and Anubis that may derail the idea of ancient contact between these faraway civilizations. For now, Xolotl and the xolotzcuintli will stand on their own and continue to serve as powerful symbols of Mexican pride and an enduring heritage.

thousands of years ago. For more information about ancient Mexico as the mother civilization of the Old World, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 110, “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” https://mexicounexplained.com//lost-continent-mu-mexican-mother-civilization/ Some similarities aside, notable differences exist between Xolotl and Anubis that may derail the idea of ancient contact between these faraway civilizations. For now, Xolotl and the xolotzcuintli will stand on their own and continue to serve as powerful symbols of Mexican pride and an enduring heritage.

REFERENCES

AKC Web site

Wikipedia