Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

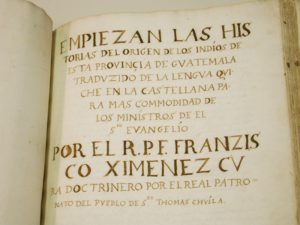

It was a hot day in Guatemala City in May of 1854. Two European adventurers – Karl Ritter von Scherzer and Moritz Wagner – had been traveling throughout the Caribbean, tropical Mexico and Guatemala for two years when they decided to explore the archives of the library at the Pontifical University of San Carlos Barromeo, now called the University of San Carlos Guatemala. The university was founded by the Spanish in 1676 and is the 4th oldest in the Americas. The Austrian and German were interested in taking a long look through the library’s oldest archives, hoping to find previously forgotten ancient texts to share with the modern world. They found just that: After days of research they discovered a manuscript dating to the early 1700s. The stacks of parchment had two columns of text, one written in the Quiché dialect of Maya, and one written in Spanish, a translation. Wagner and von Scherzer had discovered a detailed transcription of the creation story of the Maya as written by a Dominican Friar named Francisco Ximénez. Ximénez, born in Spain in 1666, had come to the tropical areas of New Spain to minister to the Maya and part of his task was to record everything he could from his new parishioners, including their history and their ancient religious beliefs. A good cleric and perhaps an even better anthropologist and historian, Ximénez eventually published a book in 1715 about the history of what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas and the country of Guatemala called, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Gvatemala. He also later wrote works on the languages of the Maya and a more detailed history of what the Spanish were then calling “The Kingdom of Guatemala.” What the European explorers found in the musty university archives on that May day in 1854 would later be called The Popol Vuh, and knowing the importance of the document they had found, Wagner and von Scherzer had the second half of the document painstakingly copied. When they went back to Europe, they had it published. As interest in archaeology and “lost civilizations” was starting to become popular in Europe in the middle of the 1800s, the publication of the second half of the newly found Maya creation story was a hit. It generated so much attention that in the following year – 1855 – a French abbot also visited the library at the Guatemalan university to take a look at the Ximénez manuscript, but unlike Wagner and von Scherzer, the French abbot did not make a copy of what he saw. Instead, he took the document, stealing it from the university, and

It was a hot day in Guatemala City in May of 1854. Two European adventurers – Karl Ritter von Scherzer and Moritz Wagner – had been traveling throughout the Caribbean, tropical Mexico and Guatemala for two years when they decided to explore the archives of the library at the Pontifical University of San Carlos Barromeo, now called the University of San Carlos Guatemala. The university was founded by the Spanish in 1676 and is the 4th oldest in the Americas. The Austrian and German were interested in taking a long look through the library’s oldest archives, hoping to find previously forgotten ancient texts to share with the modern world. They found just that: After days of research they discovered a manuscript dating to the early 1700s. The stacks of parchment had two columns of text, one written in the Quiché dialect of Maya, and one written in Spanish, a translation. Wagner and von Scherzer had discovered a detailed transcription of the creation story of the Maya as written by a Dominican Friar named Francisco Ximénez. Ximénez, born in Spain in 1666, had come to the tropical areas of New Spain to minister to the Maya and part of his task was to record everything he could from his new parishioners, including their history and their ancient religious beliefs. A good cleric and perhaps an even better anthropologist and historian, Ximénez eventually published a book in 1715 about the history of what is now the Mexican state of Chiapas and the country of Guatemala called, Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Gvatemala. He also later wrote works on the languages of the Maya and a more detailed history of what the Spanish were then calling “The Kingdom of Guatemala.” What the European explorers found in the musty university archives on that May day in 1854 would later be called The Popol Vuh, and knowing the importance of the document they had found, Wagner and von Scherzer had the second half of the document painstakingly copied. When they went back to Europe, they had it published. As interest in archaeology and “lost civilizations” was starting to become popular in Europe in the middle of the 1800s, the publication of the second half of the newly found Maya creation story was a hit. It generated so much attention that in the following year – 1855 – a French abbot also visited the library at the Guatemalan university to take a look at the Ximénez manuscript, but unlike Wagner and von Scherzer, the French abbot did not make a copy of what he saw. Instead, he took the document, stealing it from the university, and  brought it back to France. No additional translations were made of the parchments and after the abbot’s death the manuscript made its way into private hands. By the 1890s Ximénez’ document, along other written materials from colonial New Spain bundled into a 17,000-page collection, was sold to the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Popul Vuh was again “rediscovered” a few decades later and then published in English, thus exposing the Maya creation story to hundreds of millions of people. It is important to note that Ximénez wrote the document in about 1715, which was hundreds of years after the collapse of classic Maya civilization. The story he was told was coming from the descendants of the people who occupied the majestic ruins in the jungles of Mexico and Central America, many, many generations removed from the height of their civilization.

brought it back to France. No additional translations were made of the parchments and after the abbot’s death the manuscript made its way into private hands. By the 1890s Ximénez’ document, along other written materials from colonial New Spain bundled into a 17,000-page collection, was sold to the Newberry Library in Chicago. The Popul Vuh was again “rediscovered” a few decades later and then published in English, thus exposing the Maya creation story to hundreds of millions of people. It is important to note that Ximénez wrote the document in about 1715, which was hundreds of years after the collapse of classic Maya civilization. The story he was told was coming from the descendants of the people who occupied the majestic ruins in the jungles of Mexico and Central America, many, many generations removed from the height of their civilization.

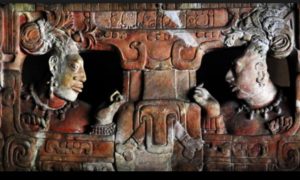

The book is divided into four parts and the Hero Twins, called Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, appear in the first two sections, as they are connected with the initial parts of the creation of the universe. According to the story, in the beginning there was a great stillness and water everywhere. There was no earth, no light, no plants, no animals and no people. Six gods, covered in blue feathers, emerged from the waters. These deities, along with the sky god, helped to create the earth. To separate the earth from the sky, the gods planted a ceiba tree, which grew up through the 13 levels of heaven and whose roots penetrated the 9 levels of the underworld. The great tree gave the gods room to create everything we now see on the earth today, first the plants, then the animals and then humans made out of mud. The humans had no souls, so the gods sent a flood and wiped them out. The gods then tried to make humans out of wood, but these humans were as defective as the ones made out of mud, so they, too were destroyed, with some of them surviving as monkeys in the jungle. The earth had plenty of plants and animals but there was no light as there was yet no sun or moon. A macaw bird called Vucub Caquix pretended to be the sun and the moon for the time being, giving light to the world. The bird had much wealth and was supreme among the animals of the earth, although he was a very greedy and despicable creature. While Vucub Caquix ruled the animals, two brothers were created, Vucub Hunahpú and Hun Hunahpú. They loved to play ball so much that the bouncing of their rubber ball disturbed the gods who lived in Xibalbá, the underworld. The gods wanted to end this noise, so they invited the brothers to a game down below. When the two arrived, they were killed and decapitated. Their heads were displayed in a cacao tree. When the underworld goddess Xquic walked by, the head of Hun Hunahpu spat on her and she became pregnant. After this, she was exiled to the earth’s surface and gave birth to two boys who would later be called the “Hero Twins,” Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. The twins had older half-brothers who hated them, and in one part of the story, the older siblings set the baby twins on an anthill as punishment for crying too much. The twins’ grandmother also did not like them, perhaps out of jealousy for their destiny and the powers she knew they would ultimately develop. The half-human, half-god twins had many adventures on the surface of the earth and like their father and uncle, they loved the Mesoamerican ball game. The twins also angered the gods living in the underworld by playing the game too loudly. The angry underworld lords tried to trick and kill the twins by luring them down to Xibalba. While there, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué faced monsters and perilous situations, including being trapped in a series of houses full of danger: the house of knives, the cold house, the jaguar house, the house of fire and the house of the rabid bats. The twins played ball games with the lords of the underworld and tried to use their athletic prowess to earn their return to the surface. At each test, the twins emerged victorious and they escaped Xibalba every time. In their last visit to the underworld, the Hero Twins defeated the gods at the ballgame and then recovered the bodies of their father and uncle and brought them to the surface of the earth.

The book is divided into four parts and the Hero Twins, called Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, appear in the first two sections, as they are connected with the initial parts of the creation of the universe. According to the story, in the beginning there was a great stillness and water everywhere. There was no earth, no light, no plants, no animals and no people. Six gods, covered in blue feathers, emerged from the waters. These deities, along with the sky god, helped to create the earth. To separate the earth from the sky, the gods planted a ceiba tree, which grew up through the 13 levels of heaven and whose roots penetrated the 9 levels of the underworld. The great tree gave the gods room to create everything we now see on the earth today, first the plants, then the animals and then humans made out of mud. The humans had no souls, so the gods sent a flood and wiped them out. The gods then tried to make humans out of wood, but these humans were as defective as the ones made out of mud, so they, too were destroyed, with some of them surviving as monkeys in the jungle. The earth had plenty of plants and animals but there was no light as there was yet no sun or moon. A macaw bird called Vucub Caquix pretended to be the sun and the moon for the time being, giving light to the world. The bird had much wealth and was supreme among the animals of the earth, although he was a very greedy and despicable creature. While Vucub Caquix ruled the animals, two brothers were created, Vucub Hunahpú and Hun Hunahpú. They loved to play ball so much that the bouncing of their rubber ball disturbed the gods who lived in Xibalbá, the underworld. The gods wanted to end this noise, so they invited the brothers to a game down below. When the two arrived, they were killed and decapitated. Their heads were displayed in a cacao tree. When the underworld goddess Xquic walked by, the head of Hun Hunahpu spat on her and she became pregnant. After this, she was exiled to the earth’s surface and gave birth to two boys who would later be called the “Hero Twins,” Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. The twins had older half-brothers who hated them, and in one part of the story, the older siblings set the baby twins on an anthill as punishment for crying too much. The twins’ grandmother also did not like them, perhaps out of jealousy for their destiny and the powers she knew they would ultimately develop. The half-human, half-god twins had many adventures on the surface of the earth and like their father and uncle, they loved the Mesoamerican ball game. The twins also angered the gods living in the underworld by playing the game too loudly. The angry underworld lords tried to trick and kill the twins by luring them down to Xibalba. While there, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué faced monsters and perilous situations, including being trapped in a series of houses full of danger: the house of knives, the cold house, the jaguar house, the house of fire and the house of the rabid bats. The twins played ball games with the lords of the underworld and tried to use their athletic prowess to earn their return to the surface. At each test, the twins emerged victorious and they escaped Xibalba every time. In their last visit to the underworld, the Hero Twins defeated the gods at the ballgame and then recovered the bodies of their father and uncle and brought them to the surface of the earth.

Arguably, the twins’ most heroic deed happened on the earth’s surface. Hunahpú took his blowgun and hit the gigantic macaw Vucub Caquix with a poison dart and caused him to fall out of his tree. The bird was not dead and was able to maul the arm of Hunahpú. The twins later tricked the macaw into giving Hunahpú’s arm back and Vucub Caquix later died of shame and thus ended his tyrannical rule over the animals on the earth. The macaw left his great wealth and power to his two demonic sons, Zipacna and Cabrakan, also known as “Creator of Mountains” and “Earthquake.” The Hero Twins tricked the two to their deaths, and the reign of the macaw family over the earth was over. Because the gigantic macaw had been pretending to be both the sun and the moon, his death and the death of his inheritors meant the earth was now left with no light. In some versions of the creation story, the twins put the bodies of their father and uncle up in the sky to become the sun and the moon. In other versions the twins climbed to the top of the gigantic ceiba tree to become the sun and moon themselves while their father became the god of corn. With ample light and a balance in the heavens and on earth, the gods were free to create the third and more permanent version of humans out of two types of corn meal, and those humans had souls. They also had the ability to worship the gods and had the skills to keep track of the calendar and of history, and thus they would remember the Hero Twins.

Arguably, the twins’ most heroic deed happened on the earth’s surface. Hunahpú took his blowgun and hit the gigantic macaw Vucub Caquix with a poison dart and caused him to fall out of his tree. The bird was not dead and was able to maul the arm of Hunahpú. The twins later tricked the macaw into giving Hunahpú’s arm back and Vucub Caquix later died of shame and thus ended his tyrannical rule over the animals on the earth. The macaw left his great wealth and power to his two demonic sons, Zipacna and Cabrakan, also known as “Creator of Mountains” and “Earthquake.” The Hero Twins tricked the two to their deaths, and the reign of the macaw family over the earth was over. Because the gigantic macaw had been pretending to be both the sun and the moon, his death and the death of his inheritors meant the earth was now left with no light. In some versions of the creation story, the twins put the bodies of their father and uncle up in the sky to become the sun and the moon. In other versions the twins climbed to the top of the gigantic ceiba tree to become the sun and moon themselves while their father became the god of corn. With ample light and a balance in the heavens and on earth, the gods were free to create the third and more permanent version of humans out of two types of corn meal, and those humans had souls. They also had the ability to worship the gods and had the skills to keep track of the calendar and of history, and thus they would remember the Hero Twins.

The Hero Twins were said to represent a kind of duality often associated with male and female in other cultures. Hunahpú, for example, excelled on the earth’s surface while Xbalanqué was the more powerful of the two in the underworld. One became the sun, one became the moon. Their roles were complimentary and the twins worked well in tandem.

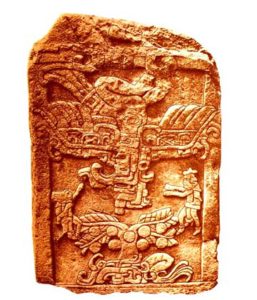

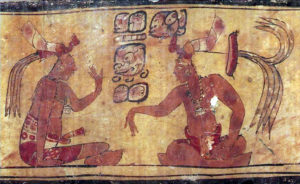

As previously mentioned, what we know of the triumphs and tragedies of the Hero Twins comes from a Spanish colonial source many centuries removed from the classical, monument-building Maya. What evidence exists of the Hero Twins stories from an earlier epoch in Maya history? In the modern Mexican state of Chiapas at a site called Izapa, there are two monumental stone carvings called stelae that clearly depict the twins in their battle with the gigantic macaw Vucub Caquix. One of the carvings, known as Stela 1, shows the Hero Twins in the presence of the bird, and even depicts Hunahpú’s injured arm. Stela 25 shows the scene of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué underneath the bird once again, and in this carving Hunahpú is clearly shooting Vacub Caquix with his blowgun. Both monuments date back to about 500 AD. In a more recent Maya record, the Dresden Codex, we also see clear depiction of the twins, and this bark paper book, the oldest book in the Americas, dates back to the 1300s. The Hero Twins most likely have been with the Maya people for thousands of years.

As previously mentioned, what we know of the triumphs and tragedies of the Hero Twins comes from a Spanish colonial source many centuries removed from the classical, monument-building Maya. What evidence exists of the Hero Twins stories from an earlier epoch in Maya history? In the modern Mexican state of Chiapas at a site called Izapa, there are two monumental stone carvings called stelae that clearly depict the twins in their battle with the gigantic macaw Vucub Caquix. One of the carvings, known as Stela 1, shows the Hero Twins in the presence of the bird, and even depicts Hunahpú’s injured arm. Stela 25 shows the scene of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué underneath the bird once again, and in this carving Hunahpú is clearly shooting Vacub Caquix with his blowgun. Both monuments date back to about 500 AD. In a more recent Maya record, the Dresden Codex, we also see clear depiction of the twins, and this bark paper book, the oldest book in the Americas, dates back to the 1300s. The Hero Twins most likely have been with the Maya people for thousands of years.

Researchers who believe in a greater Maya influence are quick to point out that Hero Twin stories exist in the legends of many North American tribes. Perhaps the most extensively documented story comes from the Navajo of the American Southwest. Their hero twins, Monster Slayer and Born for Water, were sons of Changing Woman and battled monsters and faced dangers similar to Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. The Ho-Chunk or Winnebago people of the northern US also have a similar story of the two sons of Red Horn who go on to have adventures much like the Hero Twins, including retrieving the remains of their father and uncle. In the North American archaeological record, at Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma, a neck pendant made of shell was discovered, and attributed to the prehistoric Wichita, which features a very Maya-looking male twin scene. The stories and artifacts do raise some interesting questions. It’s unknown if the legend of the Hero Twins emerged out of North America and found its way to the jungles of ancient Mexico, or the other way around, or if the similarities are just a series of strange coincidences.

Researchers who believe in a greater Maya influence are quick to point out that Hero Twin stories exist in the legends of many North American tribes. Perhaps the most extensively documented story comes from the Navajo of the American Southwest. Their hero twins, Monster Slayer and Born for Water, were sons of Changing Woman and battled monsters and faced dangers similar to Hunahpú and Xbalanqué. The Ho-Chunk or Winnebago people of the northern US also have a similar story of the two sons of Red Horn who go on to have adventures much like the Hero Twins, including retrieving the remains of their father and uncle. In the North American archaeological record, at Spiro Mounds in Oklahoma, a neck pendant made of shell was discovered, and attributed to the prehistoric Wichita, which features a very Maya-looking male twin scene. The stories and artifacts do raise some interesting questions. It’s unknown if the legend of the Hero Twins emerged out of North America and found its way to the jungles of ancient Mexico, or the other way around, or if the similarities are just a series of strange coincidences.

REFERENCES:

The Popol Vuh by Dennis Tedlock.