Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Exotic items from what is now central and southern Mexico have been found in the archaeological records of the Pueblo people in the American Southwest and those civilizations that came before them, such as the Hohokam of modern-day Arizona and the Chaco Culture of the Four Corners area. Trade networks extended throughout the Southwest, linking this 36,000 square-mile area to other regions including Mesoamerica. Items of foreign origin found by archaeologists include copper bells, remains of macaws and other tropical birds, corn-grinding tools, platform mounds, ball courts, and certain crops like maize, beans, and squash. This southern influence is also seen in pottery styles and artistic symbols, like the T-shaped doorways and headdresses found in both regions. Human figurines made of clay discovered in the Salt River and Gila River valleys of Arizona that are attributed to the Hohokam culture look strikingly like those being produced in central Mexico at the same time. Archaeologists, who are often reluctant to attribute distant similarities to long-distance contact, believe the similarities in the figurines are not coincidental.

Exotic items from what is now central and southern Mexico have been found in the archaeological records of the Pueblo people in the American Southwest and those civilizations that came before them, such as the Hohokam of modern-day Arizona and the Chaco Culture of the Four Corners area. Trade networks extended throughout the Southwest, linking this 36,000 square-mile area to other regions including Mesoamerica. Items of foreign origin found by archaeologists include copper bells, remains of macaws and other tropical birds, corn-grinding tools, platform mounds, ball courts, and certain crops like maize, beans, and squash. This southern influence is also seen in pottery styles and artistic symbols, like the T-shaped doorways and headdresses found in both regions. Human figurines made of clay discovered in the Salt River and Gila River valleys of Arizona that are attributed to the Hohokam culture look strikingly like those being produced in central Mexico at the same time. Archaeologists, who are often reluctant to attribute distant similarities to long-distance contact, believe the similarities in the figurines are not coincidental.

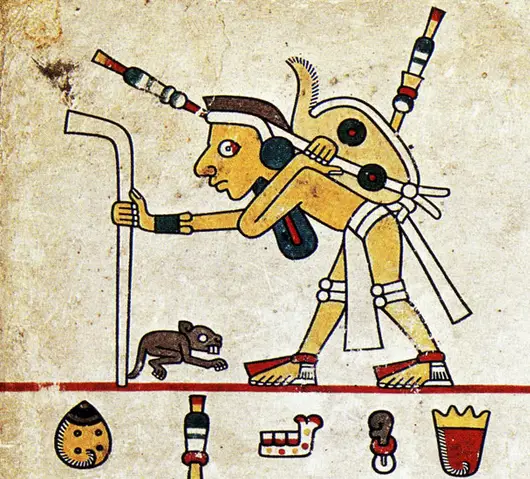

The concept of a Great Horned Serpent, like the Mesoamerican Quetzalcoatl, is found in Puebloan art and stories and even extends to the Great Plains and Mississippi Valley. Another artistic example is what has been called the Kokopelli, a famous image that crossed over into the “Santa Fe Style” that was all the rage beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Kokopelli is a mythical figure from Southwestern Native American cultures, often depicted as a humpbacked flute player with long, flowing hair. Revered by the Hopi, Zuni, and other  Pueblo tribes, Kokopelli symbolizes fertility, joy, and the spirit of music. This iconic character is believed to bring good fortune, abundant crops, and healthy babies, and is frequently featured in pottery, rock art, and textiles. As a cultural symbol, Kokopelli also represents storytelling and the sharing of knowledge and traditions through music and dance. Some researchers believe that Kokopelli could have been based on a real person, possibly a Toltec traveler who visited what is now the American Southwest over a thousand years ago. Others believe he could have been a generic representation of the pochteca, the long-distance Aztec traders often seen with packs on their backs. The theory of cultural diffusion may also explain cultural similarities between the pre-contact, complex civilizations of North America and their Mesoamerican and Central American counterparts. The Great American Southwest might be seen as an extension of “Greater Mesoamerica,” connected through indirect trade routes. The similar aesthetics are compelling, showing general likenesses while having specific differences. Without a doubt there must have been some contact, either directly or indirectly between the peoples of the American Southwest and the peoples of the complex civilizations of central and southern Mexico, and researchers are still piecing together the story. What do we know now?

Pueblo tribes, Kokopelli symbolizes fertility, joy, and the spirit of music. This iconic character is believed to bring good fortune, abundant crops, and healthy babies, and is frequently featured in pottery, rock art, and textiles. As a cultural symbol, Kokopelli also represents storytelling and the sharing of knowledge and traditions through music and dance. Some researchers believe that Kokopelli could have been based on a real person, possibly a Toltec traveler who visited what is now the American Southwest over a thousand years ago. Others believe he could have been a generic representation of the pochteca, the long-distance Aztec traders often seen with packs on their backs. The theory of cultural diffusion may also explain cultural similarities between the pre-contact, complex civilizations of North America and their Mesoamerican and Central American counterparts. The Great American Southwest might be seen as an extension of “Greater Mesoamerica,” connected through indirect trade routes. The similar aesthetics are compelling, showing general likenesses while having specific differences. Without a doubt there must have been some contact, either directly or indirectly between the peoples of the American Southwest and the peoples of the complex civilizations of central and southern Mexico, and researchers are still piecing together the story. What do we know now?

An often-cited product that was allegedly traded directly between the peoples of ancient New Mexico and those of modern-day central Mexico is turquoise. New Mexico is full of old turquoise mines dating well into prehistory. Some current mining areas have been in operation for many hundreds of years. New research shows that the turquoise used by the Aztecs might not have come from the Southwestern US, as scientists previously believed. This new research calls into question just how much the Aztecs traded with their neighbors 1,200 miles to the north. For thousands of years, people from central Mexico to the Southwestern US have loved turquoise for its pretty blue-green color. Scientists used to think that the Aztecs got their turquoise by trading with people in the American Southwest. This made sense because other items like macaw bones, rubber balls, cacao, pyrite mirrors and copper bells have been found in the Southwestern US, showing that some trade happened after 900 AD. When the Spanish first arrived in the New World, they observed that there were no turquoise mines in central Mexico, but the Aztecs used a lot of turquoise for a variety of things. During the peak of the Aztec Empire, from 1430 to 1519, they used turquoise to decorate ceremonial items, jewelry, and weapons. This stone was very important to them and even had a special place in their culture, including being mentioned in songs and poems. A 16th-century Aztec document, the Codex Mendoza, records that conquered provinces sent turquoise to the Aztec capital. These provinces were in parts of modern-day Guerrero, Puebla, Oaxaca, and Veracruz. No mines for turquoise exist in those areas today and there is no evidence that they ever existed in those areas. Scientists assumed that people from the Southwestern US traded their turquoise for goods from Mexico and farther south, so the provinces in the Codex Mendoza were importing the turquoise they sent to the Aztec capital as tribute. New chemical tests show that the turquoise in Aztec and Mixtec artifacts doesn’t match the turquoise from the Southwestern US. The question arises: how do we know where turquoise comes from?

An often-cited product that was allegedly traded directly between the peoples of ancient New Mexico and those of modern-day central Mexico is turquoise. New Mexico is full of old turquoise mines dating well into prehistory. Some current mining areas have been in operation for many hundreds of years. New research shows that the turquoise used by the Aztecs might not have come from the Southwestern US, as scientists previously believed. This new research calls into question just how much the Aztecs traded with their neighbors 1,200 miles to the north. For thousands of years, people from central Mexico to the Southwestern US have loved turquoise for its pretty blue-green color. Scientists used to think that the Aztecs got their turquoise by trading with people in the American Southwest. This made sense because other items like macaw bones, rubber balls, cacao, pyrite mirrors and copper bells have been found in the Southwestern US, showing that some trade happened after 900 AD. When the Spanish first arrived in the New World, they observed that there were no turquoise mines in central Mexico, but the Aztecs used a lot of turquoise for a variety of things. During the peak of the Aztec Empire, from 1430 to 1519, they used turquoise to decorate ceremonial items, jewelry, and weapons. This stone was very important to them and even had a special place in their culture, including being mentioned in songs and poems. A 16th-century Aztec document, the Codex Mendoza, records that conquered provinces sent turquoise to the Aztec capital. These provinces were in parts of modern-day Guerrero, Puebla, Oaxaca, and Veracruz. No mines for turquoise exist in those areas today and there is no evidence that they ever existed in those areas. Scientists assumed that people from the Southwestern US traded their turquoise for goods from Mexico and farther south, so the provinces in the Codex Mendoza were importing the turquoise they sent to the Aztec capital as tribute. New chemical tests show that the turquoise in Aztec and Mixtec artifacts doesn’t match the turquoise from the Southwestern US. The question arises: how do we know where turquoise comes from?

Turquoise forms near copper deposits when water with copper and aluminum passes through rock. The turquoise takes on the chemical makeup of the surrounding rocks. Geologists can figure out where turquoise came from by comparing its chemicals to those of known rock formations, especially looking at ratios of elements like strontium and lead. Geologist Alyson Thibodeau and her team tested turquoise tiles from offerings in the Sacred Precinct of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital. Most of these tiles were offerings to the gods and were found in the southern half of the Templo Mayor. They also tested five tiles from Mixtec mosaics found at an archaeological site in Oaxaca. The ratio of strontium in the rocks decreases as you move south from Arizona and New Mexico to Guerrero in Mexico. Most Aztec turquoise tiles had strontium ratios too low to have come from Arizona or New Mexico. The lead ratios were also a better match with places in Mexico, such as the modern states of Michoacán, Guerrero, Jalisco, or Veracruz.

This means ancient people probably didn’t bring lots of turquoise south to Mexico and Central America through trade. While other items like cacao and macaws show some long-distance trade, it wasn’t a huge amount. These items could have passed through several dozen hands on their way from the heartland of the Aztec Empire to places like Chaco Canyon in New Mexico or Mesa Verde in Colorado. Researchers are still puzzled because there are still no known turquoise deposits in central or southern Mexico today. Thibodeau and her team think the turquoise mines that supplied the Aztecs were used up before the Europeans arrived. Without these mines, geologists can only say the turquoise came from a general area in Mesoamerica, not an exact spot. Thibodeau and her team want to study turquoise from other Mesoamerican cultures, like the Toltec, Maya, Mixtec, and Tarascan, to learn more about how they mined, traded, and used turquoise because they recognize that their sample size was not extensive. More research on this specific well-traded luxury good is warranted.

This means ancient people probably didn’t bring lots of turquoise south to Mexico and Central America through trade. While other items like cacao and macaws show some long-distance trade, it wasn’t a huge amount. These items could have passed through several dozen hands on their way from the heartland of the Aztec Empire to places like Chaco Canyon in New Mexico or Mesa Verde in Colorado. Researchers are still puzzled because there are still no known turquoise deposits in central or southern Mexico today. Thibodeau and her team think the turquoise mines that supplied the Aztecs were used up before the Europeans arrived. Without these mines, geologists can only say the turquoise came from a general area in Mesoamerica, not an exact spot. Thibodeau and her team want to study turquoise from other Mesoamerican cultures, like the Toltec, Maya, Mixtec, and Tarascan, to learn more about how they mined, traded, and used turquoise because they recognize that their sample size was not extensive. More research on this specific well-traded luxury good is warranted.

As is the case in modern times, culture often travels along with traded goods. The idea of cultural diffusion briefly mentioned earlier explains the common traits seen between ancient North American civilizations and those in central and southern Mexico. The spread of ideas and goods wasn’t stopped by geographical barriers like the Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts or the Rio Grande. Items and concepts flowed through these areas, much like how trade happened along the Silk Road or through the Sahara Desert of northern Africa. The American Southwest can be considered part of a larger Mesoamerican region by default because of its interconnected trade routes. This explains why there are many similarities in the artifacts and cultures of these two areas that are separated by a vast distance. Besides the artifacts discussed previously, such as copper bells and tropical parrots, the Pueblo people, like the Hopi, have many cultural similarities with the ancient Mesoamericans, including similar pottery styles, architectural features, and symbols. While turquoise was most likely sent from north to south, most cultural influence went the opposite way, spreading north from the complex civilizations of central Mexico. Interestingly, there appear to be some linguistic similarities across these vast geographical areas which may tie them together, with words having near-identical meanings in different languages. The Hopi call their horned serpent spirit Polokon, while the Zuni of western New Mexico name it Kolowisi. Some linguists believe these names are related to the Maya name for their feathered serpent god, Kukulkán. Zuni is considered what scholars call a “language isolate,” and is unrelated to any other known language. However, some theorize it might be connected to some Maya dialects, potentially belonging to the Punutian language family. The Hopi language is definitely related to  Mexican Nahuatl, both originating from the widespread Uto-Aztecan linguistic group which comes from a much older breakaway when the Nahua-speaking peoples migrated south. For example, the Hopi word for ‘eagle’ is kwahu, and ‘house’ or ‘shelter’ is ki, closely resembling the Mexica words cuauhtl and calli, respectively. Rain gods of the American Southwest and deities related to fire and death, such as the Hopi’s Masau’u, show a distinct southern influence. The Navajo people also share traditions with the Pueblo peoples and the ancient Mesoamericans. They have stories about the Hero Twins, a common theme in Mesoamerican mythology, with evidence of the telling of the creation story involving these twins dating back almost 2,000 years in the Maya area.

Mexican Nahuatl, both originating from the widespread Uto-Aztecan linguistic group which comes from a much older breakaway when the Nahua-speaking peoples migrated south. For example, the Hopi word for ‘eagle’ is kwahu, and ‘house’ or ‘shelter’ is ki, closely resembling the Mexica words cuauhtl and calli, respectively. Rain gods of the American Southwest and deities related to fire and death, such as the Hopi’s Masau’u, show a distinct southern influence. The Navajo people also share traditions with the Pueblo peoples and the ancient Mesoamericans. They have stories about the Hero Twins, a common theme in Mesoamerican mythology, with evidence of the telling of the creation story involving these twins dating back almost 2,000 years in the Maya area.

The influence from Mesoamerica on the Southwest is seen in the large communities like Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, which have some features found in central Mexican cities such as Teotihuacan. Knowing nothing about far-reaching trade routes, ironically, in the 19th century, American settlers thought the Aztecs had built the ruins they found in the Southwest, giving them names like ‘Montezuma Castle’ and ‘Aztec Ruins.’

The intriguing connections between the American Southwest and ancient Mexico reveal complex networks of shared history, culture, and language. From the striking similarities in artifacts and mythical creatures to the overlapping linguistic roots and trade networks, it’s clear that these two faraway regions were far more interconnected than previously believed. By exploring these connections, we gain a deeper understanding of the cultural diffusion that shaped the identities and traditions of these various ancient civilizations.