Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the United States in the 1800s there was great interest in the mysterious civilizations of ancient Mexico. As the science of archaeology had not yet been born, various theories circulated about the many ruined cities and how their builders were related to other ancient cultures throughout the world. Because there was no hard science behind most any of this, amateur academics, treasure hunters, adventurers and even religious figures at the time had a whole host of explanations for these lost cities and vanished civilizations of Mexico. One of the big figures studying and exploring the Maya region in the latter half of the 1800s was the French American Augustus LePlongeon. He and his wife Alice Dixon LePlongeon used a new technique called “psychic archaeology” to sense where things were buried and then put everything together in a story using a type of intuitive channeling of events from the past. For a more detailed description of the adventures of the LePlongeons in the Yucatan, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 110 called “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” https://mexicounexplained.com/lost-continent-mu-mexican-mother-civilization/ A big turning point in the research of the LePlongeons occurred when Augustus found, by psychic means, of course, a large reclining stone figure, 7 meters underground, which he called a Chac Mool, a name meaning “red or great jaguar paw” in Yucatec Maya. He immediately declared that Chac Mool had been a ruler of Chichén Itzá and he had seen this ruler depicted throughout the ruins on stone carvings and in murals. Le Plongeon tried to spirit the statue out of Mexico to get it to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in the United States but was thwarted by government officials who apprehended the Chac Mool and took it to Mexico City. There, it was exhibited as one of the most important finds of the century and part of the Mexican patrimony that would never leave the country. Since the initial discovery of this sculpture, there have been many more similar reclining statues unearthed in Mexico and Central America. Le Plongeon’s name for this carved stone figure stuck, and these sculptures are collectively known today as chacmools.

In the United States in the 1800s there was great interest in the mysterious civilizations of ancient Mexico. As the science of archaeology had not yet been born, various theories circulated about the many ruined cities and how their builders were related to other ancient cultures throughout the world. Because there was no hard science behind most any of this, amateur academics, treasure hunters, adventurers and even religious figures at the time had a whole host of explanations for these lost cities and vanished civilizations of Mexico. One of the big figures studying and exploring the Maya region in the latter half of the 1800s was the French American Augustus LePlongeon. He and his wife Alice Dixon LePlongeon used a new technique called “psychic archaeology” to sense where things were buried and then put everything together in a story using a type of intuitive channeling of events from the past. For a more detailed description of the adventures of the LePlongeons in the Yucatan, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 110 called “The Lost Continent of Mu and the Mexican Mother Civilization.” https://mexicounexplained.com/lost-continent-mu-mexican-mother-civilization/ A big turning point in the research of the LePlongeons occurred when Augustus found, by psychic means, of course, a large reclining stone figure, 7 meters underground, which he called a Chac Mool, a name meaning “red or great jaguar paw” in Yucatec Maya. He immediately declared that Chac Mool had been a ruler of Chichén Itzá and he had seen this ruler depicted throughout the ruins on stone carvings and in murals. Le Plongeon tried to spirit the statue out of Mexico to get it to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in the United States but was thwarted by government officials who apprehended the Chac Mool and took it to Mexico City. There, it was exhibited as one of the most important finds of the century and part of the Mexican patrimony that would never leave the country. Since the initial discovery of this sculpture, there have been many more similar reclining statues unearthed in Mexico and Central America. Le Plongeon’s name for this carved stone figure stuck, and these sculptures are collectively known today as chacmools.

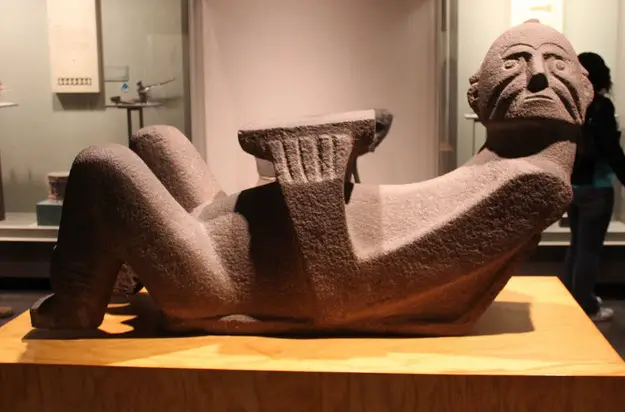

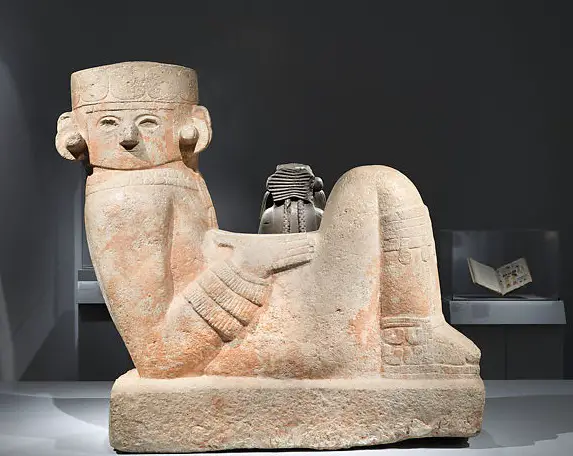

So, what exactly does a chacmool look like? Mary Ellen Miller of Yale University published a good description in her article titled “A Re-examination of the Mesoamerican Chacmool” in the March 1985 edition of The Art Bulletin. Miller states:

“The distinctive posture of the chacmool is what allows the many sculptures to be united under one term, regardless of their origin. In all cases, the figure reclines on his back, his knees bent and his body on a single axis from neck to toes. The elbows rest on the ground and support the torso creating tension as the figure strains to sit upright. The hands meet at the chest, usually holding either a disc or a vessel. The head rotates 90 degrees from the axis of the body to present a frontal face. This recumbent position represents the antithesis of aggression: it is helpless and almost defenseless humble and acquiescent.”

Since the first discovery of a chacmool by LePlongeon in 1875, there have been at least 30 of these figures found from the western Mexican state of Michoacán all the way down through Central America. All chacmools fit the general style that Mary Ellen Miller wrote about, but each sculpture is different, as if exhibiting its own distinct personality. All date to what archaeologists and other researchers refer to as the Terminal Classic Period beginning at around 800 AD. Consequently, no such reclining sculptures have ever been found at the central Mexican powerhouse of Teotihuacán, or at any of the Maya sites during the height of Classic Maya civilization. By default, they were unknown to the much earlier Olmec civilization, considered to be by some as the “Mother Civilization” of ancient Mesoamerica. Some archaeologists believe that the chacmool imagery began sometime with the Classic Maya, but this is open to a lot of speculation and interpretation. Chacmools have been found at the Toltec capital of Tula which leads some to believe that the whole concept of the chacmool began with the Toltec civilization. Fourteen chacmools have so far been discovered at the Maya site of Chichén Itzá and date to the Postclassic phase of that city, at which time most researchers believe the city had either direct Toltec influence or experienced a sort of cultural diffusion from the Toltec region of central Mexico. Chacmools have popped up here and there throughout Mesoamerica. One was found in Veracruz, at the archaeological site of Cempoala, for example, and another one was found at a remote site in Michoacán. The farthest south a chacmool was ever found was at the site of Las Mercedes in Costa Rica. In 1943 the first Aztec chacmool was excavated in the heart of Mexico City, near the modern-day intersection of Venustiano Carranza and Pino Suarez. The second Aztec chacmool was discovered with the unearthing of the Templo Mayor complex in Mexico City in the 1960s. This sculpture is showing his teeth in a non-threatening way and is painted various colors, mostly blues and reds with a golden medallion painted on his chest. The Templo Mayor chacmool is the only one painted that is known to exist. Some chacmools may exist in private collections outside of Mexico. Many chacmools found in museums cannot be adequately traced back to a specific ancient city as some were illegally taken or have come off private landholdings.

Since the first discovery of a chacmool by LePlongeon in 1875, there have been at least 30 of these figures found from the western Mexican state of Michoacán all the way down through Central America. All chacmools fit the general style that Mary Ellen Miller wrote about, but each sculpture is different, as if exhibiting its own distinct personality. All date to what archaeologists and other researchers refer to as the Terminal Classic Period beginning at around 800 AD. Consequently, no such reclining sculptures have ever been found at the central Mexican powerhouse of Teotihuacán, or at any of the Maya sites during the height of Classic Maya civilization. By default, they were unknown to the much earlier Olmec civilization, considered to be by some as the “Mother Civilization” of ancient Mesoamerica. Some archaeologists believe that the chacmool imagery began sometime with the Classic Maya, but this is open to a lot of speculation and interpretation. Chacmools have been found at the Toltec capital of Tula which leads some to believe that the whole concept of the chacmool began with the Toltec civilization. Fourteen chacmools have so far been discovered at the Maya site of Chichén Itzá and date to the Postclassic phase of that city, at which time most researchers believe the city had either direct Toltec influence or experienced a sort of cultural diffusion from the Toltec region of central Mexico. Chacmools have popped up here and there throughout Mesoamerica. One was found in Veracruz, at the archaeological site of Cempoala, for example, and another one was found at a remote site in Michoacán. The farthest south a chacmool was ever found was at the site of Las Mercedes in Costa Rica. In 1943 the first Aztec chacmool was excavated in the heart of Mexico City, near the modern-day intersection of Venustiano Carranza and Pino Suarez. The second Aztec chacmool was discovered with the unearthing of the Templo Mayor complex in Mexico City in the 1960s. This sculpture is showing his teeth in a non-threatening way and is painted various colors, mostly blues and reds with a golden medallion painted on his chest. The Templo Mayor chacmool is the only one painted that is known to exist. Some chacmools may exist in private collections outside of Mexico. Many chacmools found in museums cannot be adequately traced back to a specific ancient city as some were illegally taken or have come off private landholdings.

Although there are some 30 to 50 chachmools thought to exist, researchers still debate their meaning, although some solid interpretations are now gaining wider acceptance among Mesoamerican archaeologists. The first interpretation came from the one who gave the sculpture its name, the first discoverer of this genre, the French American antiquarian and adventurer Augustus LePlongeon. LePlongeon stated, “It is not an idol, but a true portrait of a man who has lived an earthly life. I have seen him represented in battle, in councils and in court receptions.” His interpretation was based on channeling the spirits of the ancient Maya as part of his method of psychic archaeology used at Chichén Itzá and other places. To LePlongeon, not only was the sculpture of a real person but this mythical ruler Chac Mool was also known as Prince Coh. Chac Mool was the brother of Prince Aac, the evil lord of Uxmal. Prince Aac defeated Chac Mool in mortal combat and Chac Mool’s widow came to rule the kingdom as Queen Móo. The territory of Chichén Itzá and its surroundings became known as the Kingdom of Móo. Queen Móo was then forced to marry her evil brother-in-law Prince Aac, at which point she fled to Egypt where she was revered as the goddess Isis.

While the LePlongeon “inventive” interpretation of the chachmool may have been gripping to read about in the late 1880s, serious scholarly attention given to these statues did not begin until the latter half of the 20th Century. Researchers who began studying chacmools put forth the idea that the sculptures functions varied on culture, geography, and the time period during which they were fashioned. There is great consensus among archaeologists that chacmools were not worshipped as they were not found in the inner sanctums of temples or other holy places. Researchers now believe that chacmools may have served three different functions.

While the LePlongeon “inventive” interpretation of the chachmool may have been gripping to read about in the late 1880s, serious scholarly attention given to these statues did not begin until the latter half of the 20th Century. Researchers who began studying chacmools put forth the idea that the sculptures functions varied on culture, geography, and the time period during which they were fashioned. There is great consensus among archaeologists that chacmools were not worshipped as they were not found in the inner sanctums of temples or other holy places. Researchers now believe that chacmools may have served three different functions.

The first theory is that the chacmool was a simple offering table and received gifts from the devout seeking supernatural assistance. The offerings could have been food, alcoholic beverages, tobacco, feathers, cacao beans or incense. The chacmool found in Costa Rica is holding a form of metate or corn grinding stone in its hands which is resting on his belly in typical fashion. This would seem to be a receptacle for offerings of food. In Nahuatl, the Aztecs called a small table for offerings a tlamanalco. In some cases, the chacmool may have functioned as a sort of public tlamanalco.

The second and third interpretations of the function of chacmools have to do with human sacrifice. This is a much-maligned topic, especially among certain revisionists or those who wish to have a more romantic view of the Aztecs and their empire. A chacmool from Tlaxcala has a carving of a bloodied heart on its underside which has led some researchers to believe that a chacmool served as an offering table for what the Nahua-speaking peoples called a cuauhxicalli. A cuauhxicalli was a receptacle to receive blood and hearts in human sacrifice. The scholars who back this second interpretation believe that after a victim was sacrificed, an offering was made in the removable cuauhxicalli and placed on the center of the chacmool, on that flat surface or slightly indented area on the figure’s belly.

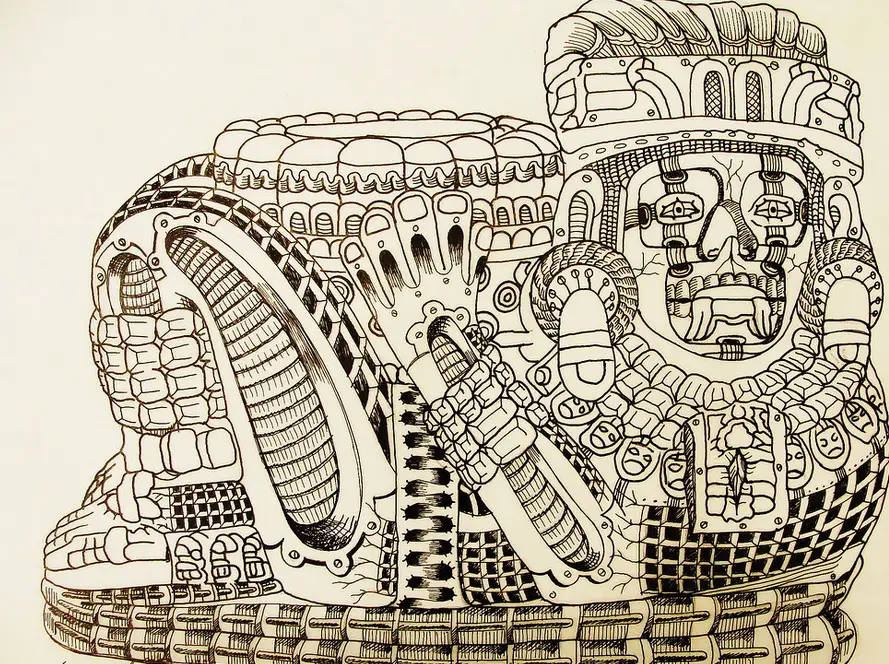

The last most widely discussed theory on the purpose of the chacmool has the sculpture as serving as an actual sacrificial table called a techcatl in the Nahuatl language. Victims were stretched across the middle of the chacmool and their hearts were extracted. The main source for this theory comes from a manuscript called the Crónica Mexicayotl written by an Aztec source a few decades after the Conquest. In this crónica, the author describes war captives being sacrificed on a large stone that was sculpted in partially human form with a twisted head. This is the only surviving colonial account of a possible use of a chacmool and the document itself has been called into question, with various scholars arguing over authorship or whether it is even an authentic chronicle written by an indigenous scholar in the 1500s. The association with the god Tlaloc at the Templo Mayor in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán is used by the human sacrifice theorists to further the theory of chacmools used as tables for human sacrifice. Some of the water imagery carved on many chacmools make the sculpture appear as if it is floating on water. This water imagery may symbolize a state in between the earthly and the supernatural realms, suggesting the chacmools may have been messengers to or intermediaries with the gods. The author and Yale professor Mary Ellen Miller previously mentioned also tends to believe that the chacmool was connected with human sacrifice, either as a table for the offering bowls of hearts and blood, or as a place where sacrifices actually took place. She notes that the reclining, defenseless position of the chacmool, with its bent elbows and knees is the position of many depictions of captives in ancient Mesoamerican art. The only thing that these researchers are missing, it seems, is the logistical problems the chacmool faces if it is used as a sacrificial table. Most chachmools have too small a middle surface area to serve this function. It would be nearly impossible to drape a victim over one of the sculptures to sacrifice that unlucky person to the gods. Yet, the theory persists.

The last most widely discussed theory on the purpose of the chacmool has the sculpture as serving as an actual sacrificial table called a techcatl in the Nahuatl language. Victims were stretched across the middle of the chacmool and their hearts were extracted. The main source for this theory comes from a manuscript called the Crónica Mexicayotl written by an Aztec source a few decades after the Conquest. In this crónica, the author describes war captives being sacrificed on a large stone that was sculpted in partially human form with a twisted head. This is the only surviving colonial account of a possible use of a chacmool and the document itself has been called into question, with various scholars arguing over authorship or whether it is even an authentic chronicle written by an indigenous scholar in the 1500s. The association with the god Tlaloc at the Templo Mayor in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán is used by the human sacrifice theorists to further the theory of chacmools used as tables for human sacrifice. Some of the water imagery carved on many chacmools make the sculpture appear as if it is floating on water. This water imagery may symbolize a state in between the earthly and the supernatural realms, suggesting the chacmools may have been messengers to or intermediaries with the gods. The author and Yale professor Mary Ellen Miller previously mentioned also tends to believe that the chacmool was connected with human sacrifice, either as a table for the offering bowls of hearts and blood, or as a place where sacrifices actually took place. She notes that the reclining, defenseless position of the chacmool, with its bent elbows and knees is the position of many depictions of captives in ancient Mesoamerican art. The only thing that these researchers are missing, it seems, is the logistical problems the chacmool faces if it is used as a sacrificial table. Most chachmools have too small a middle surface area to serve this function. It would be nearly impossible to drape a victim over one of the sculptures to sacrifice that unlucky person to the gods. Yet, the theory persists.

As with many artifacts from ancient Mexico, the chacmool is still somewhat mysterious and open to a wide range of interpretations by archaeologists and other researchers. As more is discovered, more will be learned, and perhaps one day we will know the real purpose of this very enigmatic sculpture.

REFERENCES

Miller, Mary Ellen. “A Re-Examination of the Mesoamerican Chacmool.” The Art Bulletin 67, no. 1 (1985): 7–17.