Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

On July 11, 1598, Don Juan de Oñate and his caravan of over a thousand people entered the village of Ohkay Owingeh in the upper Rio Grande Valley. It was here where he would establish the capital of the new Kingdom of New Mexico. After years of planning, great personal expense and considerable bureaucratic hassle from both Mexico City and Madrid, New Mexico was finally a reality with Oñate as its first Spanish governor. The Spanish explorer Coronado had passed through here nearly 60 years before, fueled by legendary cities full of fabulous riches, known at the time as the Seven Cities of Gold or the Seven Cities of Cibola, which were supposedly located in the Rio Grande Valley. For more information about these legends, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 27: https://mexicounexplained.com/seven-cities-gold/ Oñate had staked a great personal fortune to follow in Coronado’s footsteps in hopes of discovering abundant mineral wealth and with the possibilities of undiscovered rich native kingdoms rooted deeply in the back of his mind. There was much blank space on the map north of what is now the modern Mexican state of Chihuahua and Don Juan, who was born in Zacatecas, had spent most of his life preparing for this expedition of colonization and exploration penetrating deep into the heart of North America. The village of Ohkay Owingeh, which means “Place of the Strong People” in the Tewa language, was renamed San Juan de los Caballeros on July 12, 1598, in honor of Don Juan de Oñate’s patron saint, Saint John the Baptist. The newcomers started to settle in and to build something new in this far-flung territory of Spain located nearly 1,500 miles from Mexico City. In September of the same year, 1598, a curious person showed up at San Juan Pueblo. He was indigenous but didn’t look like the inhabitants of the Rio Grande Valley. He introduced himself in Spanish to the first Europeans he saw in the village and called himself Jusepe Gutiérrez. He was immediately brought before Governor Oñate.

On July 11, 1598, Don Juan de Oñate and his caravan of over a thousand people entered the village of Ohkay Owingeh in the upper Rio Grande Valley. It was here where he would establish the capital of the new Kingdom of New Mexico. After years of planning, great personal expense and considerable bureaucratic hassle from both Mexico City and Madrid, New Mexico was finally a reality with Oñate as its first Spanish governor. The Spanish explorer Coronado had passed through here nearly 60 years before, fueled by legendary cities full of fabulous riches, known at the time as the Seven Cities of Gold or the Seven Cities of Cibola, which were supposedly located in the Rio Grande Valley. For more information about these legends, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 27: https://mexicounexplained.com/seven-cities-gold/ Oñate had staked a great personal fortune to follow in Coronado’s footsteps in hopes of discovering abundant mineral wealth and with the possibilities of undiscovered rich native kingdoms rooted deeply in the back of his mind. There was much blank space on the map north of what is now the modern Mexican state of Chihuahua and Don Juan, who was born in Zacatecas, had spent most of his life preparing for this expedition of colonization and exploration penetrating deep into the heart of North America. The village of Ohkay Owingeh, which means “Place of the Strong People” in the Tewa language, was renamed San Juan de los Caballeros on July 12, 1598, in honor of Don Juan de Oñate’s patron saint, Saint John the Baptist. The newcomers started to settle in and to build something new in this far-flung territory of Spain located nearly 1,500 miles from Mexico City. In September of the same year, 1598, a curious person showed up at San Juan Pueblo. He was indigenous but didn’t look like the inhabitants of the Rio Grande Valley. He introduced himself in Spanish to the first Europeans he saw in the village and called himself Jusepe Gutiérrez. He was immediately brought before Governor Oñate.

Jusepe told a fascinating tale in broken Spanish alternating with Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec Empire that many people on the Oñate expedition could understand. Jusepe was born in Culiacán, which is now the capital city of the modern Mexican state of Sinaloa. Jusepe’s parents were Mexica or Aztec from the Valley of Mexico who were servants to a family of Spaniards and had relocated to the western part of New Spain. So how did this humble Nahua man end up so far from home? New Mexico must have seemed like the ends of the earth in the late 16th Century. Jusepe told Oñate of a failed and illegal expedition north that he took part in. Two men, Antonio Gutiérrez de Humaña and Francisco Leyba de Bonilla, left the northern fringes of New Spain with a handful of companions sometime in 1594, bound for New Mexico and points beyond. This expedition was unsanctioned by the royal authorities in Mexico City, and no one had gone into what would later be called New Mexico on an official basis since Coronado’s expedition in the early 1540s. Jusepe told governor Oñate that after arriving in New Mexico, the small group spent about a year in the village of Po-Wo-Geh-Owingeh, “The Place Where the Water Cuts Through,” now known as San Ildefonso Pueblo. While spending time in the pueblo the Humaña and Leyba expedition  was dazzled by stories of great cities to the east where kings drank out of cups of gold that hung from trees. Food was plentiful in these cities and the surrounding plains were the home to herds of gigantic cattle. The Humaña/Leyba group had heard stories of this mythical place which was called “Quivira” by the members of Coronado’s expedition. It was also a name that featured prominently on Spanish maps of North America used to denote the vast area north of the modern US state of Texas. Just a few years before, Jusepe and the others made the journey to this land of Quivira, which took well over a month, and were amazed at the massive city they found stretching some 25 miles long and serving as the home to over 20,000 people. Archaeologists today believe that the city Jusepe called “The Great Settlement” was the ancient city of Etzanoa, located near modern day Arkansas City, Kansas at the confluence of the Arkansas and the Walnut Rivers. The Spaniards called the people at “The Great Settlement” “Quivirans” although we know now that they were the Wichita People whose descendants still live in the area. These Quivirans lived in large huts made of straw and wood and although there was abundant food to support the large population at Etzanoa, there wasn’t the gold and riches the Spaniards expected. The people of “The Great Settlement” told the newcomers that they needed to go farther afield to encounter the real wealth, so the expedition turned north. Somewhere along the way, Humaña and Leyba fought and Jusepe abandoned the expedition, retracing the trail back to New Mexico. While somewhere in the eastern part of the modern American state of New Mexico, Jusepe was captured by the Apache and lived among them for a year, even learning their language. Jusepe did not know what became of the rest of the people on the Humaña/Leyba expedition. He assumed they were either captured or they died of starvation, but there was an outside chance that they might have made it to that part of the land of Quivira that had all the gold and riches promised in the fanciful stories.

was dazzled by stories of great cities to the east where kings drank out of cups of gold that hung from trees. Food was plentiful in these cities and the surrounding plains were the home to herds of gigantic cattle. The Humaña/Leyba group had heard stories of this mythical place which was called “Quivira” by the members of Coronado’s expedition. It was also a name that featured prominently on Spanish maps of North America used to denote the vast area north of the modern US state of Texas. Just a few years before, Jusepe and the others made the journey to this land of Quivira, which took well over a month, and were amazed at the massive city they found stretching some 25 miles long and serving as the home to over 20,000 people. Archaeologists today believe that the city Jusepe called “The Great Settlement” was the ancient city of Etzanoa, located near modern day Arkansas City, Kansas at the confluence of the Arkansas and the Walnut Rivers. The Spaniards called the people at “The Great Settlement” “Quivirans” although we know now that they were the Wichita People whose descendants still live in the area. These Quivirans lived in large huts made of straw and wood and although there was abundant food to support the large population at Etzanoa, there wasn’t the gold and riches the Spaniards expected. The people of “The Great Settlement” told the newcomers that they needed to go farther afield to encounter the real wealth, so the expedition turned north. Somewhere along the way, Humaña and Leyba fought and Jusepe abandoned the expedition, retracing the trail back to New Mexico. While somewhere in the eastern part of the modern American state of New Mexico, Jusepe was captured by the Apache and lived among them for a year, even learning their language. Jusepe did not know what became of the rest of the people on the Humaña/Leyba expedition. He assumed they were either captured or they died of starvation, but there was an outside chance that they might have made it to that part of the land of Quivira that had all the gold and riches promised in the fanciful stories.

Where did the legend of Quivira come from exactly? The word “Quivira” first appears in the chronicles of the Coronado expedition when a Plains Indian residing at Pecos Pueblo told stories of his native country far to the east. This man was nicknamed “The Turk” by Coronado. The Turk described the faraway place “as a land rich in gold, silver and fabrics.” Although The Turk did not call his homeland “Quivira”, the Spanish started calling it that. Scholars argue about where the name came from. Some believe it was a Spanish misinterpretation of a Plains Indian place name. Others believe that the name has its roots in Arabic, like so many geographical place names back in Spain. In this case, the Arabic word quivír signifies “great”, as in the name of the large river flowing through Seville called Guádalquivir. There is another explanation for the origin of the name Quivira. The motto of the Coronado expedition was “Quién viverá, verá,” meaning in English, “He who lives, will see.” Coronado’s men shortened that phrase to “Quién viverá” and then to “Qui’viverá.” Ultimately, this became, simply “Quivira” and then was used to describe the kingdom they were going to find that they thought would rival the one conquered by Hernán Cortés just 20 years earlier. The Coronado expedition headed east and encountered agriculturally rich villages in what is now central Kansas, but they did not find the golden empire they were looking for. When Coronado returned to Mexico City, the viceroy proclaimed that he would not fund any more expeditions looking for this land of Quivira, but in the viceregal capital of New Spain the stories and rumors about this place persisted and those wanting to make a fortune or a name for themselves dreamt of heading for the mythical land.

Where did the legend of Quivira come from exactly? The word “Quivira” first appears in the chronicles of the Coronado expedition when a Plains Indian residing at Pecos Pueblo told stories of his native country far to the east. This man was nicknamed “The Turk” by Coronado. The Turk described the faraway place “as a land rich in gold, silver and fabrics.” Although The Turk did not call his homeland “Quivira”, the Spanish started calling it that. Scholars argue about where the name came from. Some believe it was a Spanish misinterpretation of a Plains Indian place name. Others believe that the name has its roots in Arabic, like so many geographical place names back in Spain. In this case, the Arabic word quivír signifies “great”, as in the name of the large river flowing through Seville called Guádalquivir. There is another explanation for the origin of the name Quivira. The motto of the Coronado expedition was “Quién viverá, verá,” meaning in English, “He who lives, will see.” Coronado’s men shortened that phrase to “Quién viverá” and then to “Qui’viverá.” Ultimately, this became, simply “Quivira” and then was used to describe the kingdom they were going to find that they thought would rival the one conquered by Hernán Cortés just 20 years earlier. The Coronado expedition headed east and encountered agriculturally rich villages in what is now central Kansas, but they did not find the golden empire they were looking for. When Coronado returned to Mexico City, the viceroy proclaimed that he would not fund any more expeditions looking for this land of Quivira, but in the viceregal capital of New Spain the stories and rumors about this place persisted and those wanting to make a fortune or a name for themselves dreamt of heading for the mythical land.

Some 60 years after Coronado, once firmly established in New Mexico, governor Oñate put together his own expedition in search of Quivira. It was June of 1601 when the expedition to the eastern plains began. Oñate left his lieutenant-governor and captain-general in charge of the New Mexico colony, a man named Francisco de Sosa Peñalosa. Oñate journeyed past Galisteo Pueblo and across the Pecos River to the edge of the Great Plains. A member of the expedition wrote this in his diary about the part of the trip that took them through the Texas panhandle and across what is now known as the Canadian River:

“We found it green and delightful, bordered everywhere by vines and fruit trees, whereupon we came to realize that it was one of the best rivers that we had seen anywhere in the Indies.”

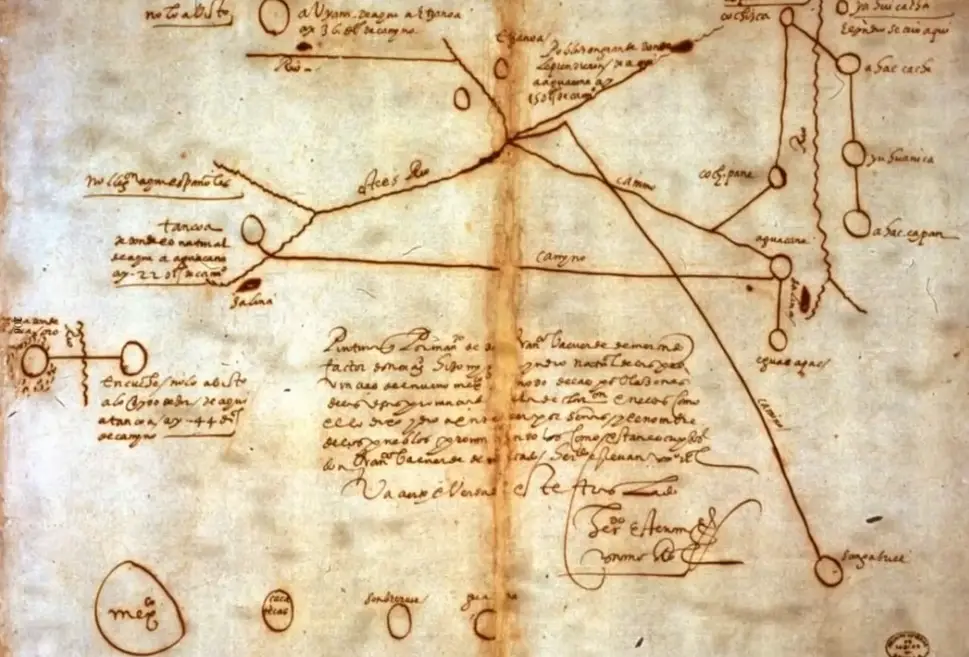

Oñate headed north and encountered the large herds of buffalo described by Coronado. When the expedition made it to the Arkansas River, Oñate proclaimed that they had finally made it to the land of Quivira. The tired group of Spaniards eventually made it to Jusepe’s “Great Settlement” and were equally as disappointed as Humaña and Leyba must have been when they did not find the gold, silver and chests full of precious jewels that they had dreamed about from the stories they had heard. The large round houses thatched with prairie grass in the massive, well-organized city  were impressive, along with the large fields of corn and squash, but this was nothing to write to the king of Spain about. The tens of thousands of souls were ripe for saving, and the land had great agricultural promise, but beyond that, the province of Quivira was too far away and not economically viable to plant a permanent Spanish colony there. The nagging feeling of “more beyond” still gnawed at Oñate, though, and he thought of another angle that might allow for more reinforcements and other resources to be sent his way. He noticed that the people of status in the “Great Settlement” and in other larger villages nearby were wearing seashells for adornment. Oñate reasoned that just north of them must have been the fabled Strait of Anian, also known later to the English as the Northwest Passage, that was said to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Confirming the existence of this waterway would give Spain a great commercial and strategic advantage. The people of the plains did tell of huge bodies of water to the north, but the seashells they were wearing ended up in the central plains from old trade networks that came from the Texas gulf coast and not from those northern bodies of water that were probably the Great Lakes. Oñate eventually returned to New Mexico, bringing some Wichita youths with him, and he was eager to report his findings to the viceroy. He sent the youths to Mexico City with a small envoy. One of the Wichita boys – later christened “Miguel” – ended up drawing a map of Quivira to the delight of the viceroy and his staff. The map still exists. After traveling nearly 2,000 miles, young Miguel and his companions ended up being servants to wealthy Spanish families in Mexico City, never to see their homeland again.

were impressive, along with the large fields of corn and squash, but this was nothing to write to the king of Spain about. The tens of thousands of souls were ripe for saving, and the land had great agricultural promise, but beyond that, the province of Quivira was too far away and not economically viable to plant a permanent Spanish colony there. The nagging feeling of “more beyond” still gnawed at Oñate, though, and he thought of another angle that might allow for more reinforcements and other resources to be sent his way. He noticed that the people of status in the “Great Settlement” and in other larger villages nearby were wearing seashells for adornment. Oñate reasoned that just north of them must have been the fabled Strait of Anian, also known later to the English as the Northwest Passage, that was said to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Confirming the existence of this waterway would give Spain a great commercial and strategic advantage. The people of the plains did tell of huge bodies of water to the north, but the seashells they were wearing ended up in the central plains from old trade networks that came from the Texas gulf coast and not from those northern bodies of water that were probably the Great Lakes. Oñate eventually returned to New Mexico, bringing some Wichita youths with him, and he was eager to report his findings to the viceroy. He sent the youths to Mexico City with a small envoy. One of the Wichita boys – later christened “Miguel” – ended up drawing a map of Quivira to the delight of the viceroy and his staff. The map still exists. After traveling nearly 2,000 miles, young Miguel and his companions ended up being servants to wealthy Spanish families in Mexico City, never to see their homeland again.

Scholars still debate the whole Quivira narrative. Was there more to this fabulous kingdom to the east? Some believe that the natives were making up stories just to get the Spanish away from them and lost in the Great Plains, never to be seen again. Others think the stories behind Quivira might have been based on something more tangible. About 1,000 years before the Europeans arrived, what has been called the Mississippian people had large urban centers in modern-day Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas and Kentucky, with one notable city, Cahokia, having over 40,000 inhabitants at its height. With its pyramids and ceremonial sites, perhaps Cahokia is the Quivira of legend, the wealthy city to the east, but we may never know.

REFERENCES

The following is an excellent book! You can get it on Amazon here (we are Amazon affiliates): https://amzn.to/3VJL0HR

Simmons, Marc. The Last Conquistador: Juan de Oñate and the Settling of the Far Southwest. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.