Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In 1987, the people of the remote village of El Macayal in the Mexican state of Veracruz wanted to come up with ways to increase their income. Because El Macayal is located on the floodplains of the Coatzacoalcos River system, the villagers were never lacking fresh water. The people of the village decided to raise fish commercially in artificial ponds that they would dig by hand near a local freshwater spring on the slopes of a hill they called Cerro Manatí, or Manatee Hill. Soon after they began digging in the muddy soil, they began to find interesting artifacts. These included pieces of old pottery, stone axes, rubber balls, assorted bones and some strange wooden objects that they assumed were old tree roots. The people involved in this fish pond project were finding too many interesting things and could not ignore the significance of what they were discovering. After unearthing hundreds of objects, the villagers decided to tell the authorities about their finds. They had hoped that if they had stumbled upon a major archaeological site that the government might develop the area into a draw for tourists and perhaps then the village of El Macayal would get electricity and other services like indoor plumbing and telephones. With bags full of artifacts, a handful of villagers made the long journey – about 100 miles – to the city of Veracruz to meet with officials in the state office of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH. When they had their meeting, the INAH officials showed mild interest in the discoveries at El Macayal and promised to follow up with the villagers at some future time. The people in the isolated village waited for months with not a word from INAH’s Veracruz office. More months passed, so the villagers decided to make the journey again, and this time with more artifacts and more impressive finds. The INAH people then decided to take notice, and within a few more months they sent archaeologists to the site outside the town of El Macayal which consisted of a hill surrounded by dismal swamps and shallow lagoons. An archaeologist working at the site was quoted as saying that digging here was like digging in “gelatina caliente” or, in English, “warm Jell-o.” Although difficult to get to and laborious to excavate, what was uncovered in the bogs in this remote part of Veracruz would help rewrite the history of ancient Mexico.

In 1987, the people of the remote village of El Macayal in the Mexican state of Veracruz wanted to come up with ways to increase their income. Because El Macayal is located on the floodplains of the Coatzacoalcos River system, the villagers were never lacking fresh water. The people of the village decided to raise fish commercially in artificial ponds that they would dig by hand near a local freshwater spring on the slopes of a hill they called Cerro Manatí, or Manatee Hill. Soon after they began digging in the muddy soil, they began to find interesting artifacts. These included pieces of old pottery, stone axes, rubber balls, assorted bones and some strange wooden objects that they assumed were old tree roots. The people involved in this fish pond project were finding too many interesting things and could not ignore the significance of what they were discovering. After unearthing hundreds of objects, the villagers decided to tell the authorities about their finds. They had hoped that if they had stumbled upon a major archaeological site that the government might develop the area into a draw for tourists and perhaps then the village of El Macayal would get electricity and other services like indoor plumbing and telephones. With bags full of artifacts, a handful of villagers made the long journey – about 100 miles – to the city of Veracruz to meet with officials in the state office of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH. When they had their meeting, the INAH officials showed mild interest in the discoveries at El Macayal and promised to follow up with the villagers at some future time. The people in the isolated village waited for months with not a word from INAH’s Veracruz office. More months passed, so the villagers decided to make the journey again, and this time with more artifacts and more impressive finds. The INAH people then decided to take notice, and within a few more months they sent archaeologists to the site outside the town of El Macayal which consisted of a hill surrounded by dismal swamps and shallow lagoons. An archaeologist working at the site was quoted as saying that digging here was like digging in “gelatina caliente” or, in English, “warm Jell-o.” Although difficult to get to and laborious to excavate, what was uncovered in the bogs in this remote part of Veracruz would help rewrite the history of ancient Mexico.

In the decades of ongoing research at El Manatí, archaeologists have constructed theories as to what was going on at the site and why. The consensus was that the natural sweetwater spring and the hill itself served as a sacred place which drew pilgrims and elites for centuries. Because of the artifacts found at the site, and because of its location and the dates involved, El Manatí was undoubtedly used and occupied by the Olmecs. Not much is known about the specifics of Olmec religion other than what researchers can assume based on what was known about religions from later times in ancient Mexico. There are certain themes that have been consistent across thousands of years and across different cultures from which these assumptions are based. The El Manatí site has a prominent hill and an abundant freshwater spring. Hills and mountains were held to be sacred spaces to most ancient Mexican cultures, and some of them even went so far as to create artificial ones in the form of pyramids and gigantic mounds. Cerro Manatí, as a natural hill among the swamps and lagoons of the region, stood out as something important. The spring on the hill is also significant. Wells and springs have had sacred meaning in ancient Mexico going all the way up to the Aztecs at the time of first contact with the Spanish. The Maya, considered the immediate inheritors of Olmec culture, also put profound importance on sacred springs, wells and watering holes. For more information about this concept as it related to the Maya specifically, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 251, “Cenotes of the Maya.” https://mexicounexplained.com/cenotes-of-the-maya/ Finally, the mineral hematite is found in abundance on the hill, and in many ancient Mexican cultures this natural substance was ground up to be used in a red pigment to symbolize blood.

In the decades of ongoing research at El Manatí, archaeologists have constructed theories as to what was going on at the site and why. The consensus was that the natural sweetwater spring and the hill itself served as a sacred place which drew pilgrims and elites for centuries. Because of the artifacts found at the site, and because of its location and the dates involved, El Manatí was undoubtedly used and occupied by the Olmecs. Not much is known about the specifics of Olmec religion other than what researchers can assume based on what was known about religions from later times in ancient Mexico. There are certain themes that have been consistent across thousands of years and across different cultures from which these assumptions are based. The El Manatí site has a prominent hill and an abundant freshwater spring. Hills and mountains were held to be sacred spaces to most ancient Mexican cultures, and some of them even went so far as to create artificial ones in the form of pyramids and gigantic mounds. Cerro Manatí, as a natural hill among the swamps and lagoons of the region, stood out as something important. The spring on the hill is also significant. Wells and springs have had sacred meaning in ancient Mexico going all the way up to the Aztecs at the time of first contact with the Spanish. The Maya, considered the immediate inheritors of Olmec culture, also put profound importance on sacred springs, wells and watering holes. For more information about this concept as it related to the Maya specifically, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 251, “Cenotes of the Maya.” https://mexicounexplained.com/cenotes-of-the-maya/ Finally, the mineral hematite is found in abundance on the hill, and in many ancient Mexican cultures this natural substance was ground up to be used in a red pigment to symbolize blood.

Chronologically, archaeologists have broken down the El Manatí site into three phases or timeframes. The Manatí A Phase began around 1700 BC and spanned about a hundred years, lasting until about 1600 BC. The second era at the site has been labeled the Manatí B Phase. This phase began in 1700 BC and ended about 1050 BC, a period of about 550 years. The third and final phase is named after the neighboring village and is called the Macayal Phase. This lasted about one hundred and fifty years and went from 1050 BC to about 900 BC. The phase breakdown is based on the types of artifacts found at the site. El Manatí has no permanent structures or monumental art or architecture of any kind. There are no pyramids, palaces, or gigantic Atlantean sculptures.

Chronologically, archaeologists have broken down the El Manatí site into three phases or timeframes. The Manatí A Phase began around 1700 BC and spanned about a hundred years, lasting until about 1600 BC. The second era at the site has been labeled the Manatí B Phase. This phase began in 1700 BC and ended about 1050 BC, a period of about 550 years. The third and final phase is named after the neighboring village and is called the Macayal Phase. This lasted about one hundred and fifty years and went from 1050 BC to about 900 BC. The phase breakdown is based on the types of artifacts found at the site. El Manatí has no permanent structures or monumental art or architecture of any kind. There are no pyramids, palaces, or gigantic Atlantean sculptures.

The wealth of artifacts thus recovered at El Manatí is amazing by any archaeological standard. These artifacts were not haphazardly thrown into the swamp or buried carelessly on the side of the hill. Rather, they were carefully arranged which implies thought and ritual intent. Some of the first things discovered when the villagers began digging their fish ponds were stone axes. These axes were made of various substances, including serpentine, jade, andesite and schist, which were considered to be exotic materials and not sourced locally. These imported substances required elaborate trade networks in order to end up at El Manatí and cost a great deal to produce. In the later phase at the site, ceremonial axes were offered with a limestone chopping block attached. Archaeologist are baffled at the meaning behind these.

Archaeologists are not in agreement about the presence of infant bones and remains of unborn babies found ritually buried at the site. Some believe that the babies and fetuses were made as offerings to the gods after death or they might have been buried at El Manatí because it was a sacred and special place. Other researchers theorize that the infants and unborn babies may have been sacrificed to the gods, as the skeletons have not been found intact, but were discovered dismembered. Those who espouse this theory link the ritual sacrifice of children to the rain and water god Tlaloc among the Aztecs to the water-related sacrifices at El Manatí. At other sites throughout the Olmec world, archaeologists have unearthed sculptures of crying babies. Some researchers believe that baby tears may have invoked the rain gods in the belief systems of many ancient Mexicans including the Olmecs. At the El Manatí site there could be a tie-in with infant sacrifice and appealing to the Olmec rain or water gods.

In the El Manatí swamps archaeologist found the earliest examples of rubber seen anywhere in Mexico thus far. In 1989, 14 rubber balls were unearthed at the site, and they correspond to El Manatí’s earliest phase, dating to around 1700 BC. The balls were made from the sap or milky latex of the rubber tree and combined with juice from a flowering plant that is a member of the morning glory family. Archaeologists are divided as to what they think the presence of the balls meant. The rubber balls are much like those used in the Mesoamerican ball game but also may have had some deeper ritual significance. In some ancient Mexican cultures, the latex sap of the rubber tree represented blood, and in some rituals was used in the place of human blood. When the Spanish arrived in central Mexico some physical representations of local water deities were adorned with papers splashed in latex from the rubber tree. As finished rubber has also been associated with various water gods, it makes sense that finely crafted rubber artifacts would be found at a site like El Manatí.

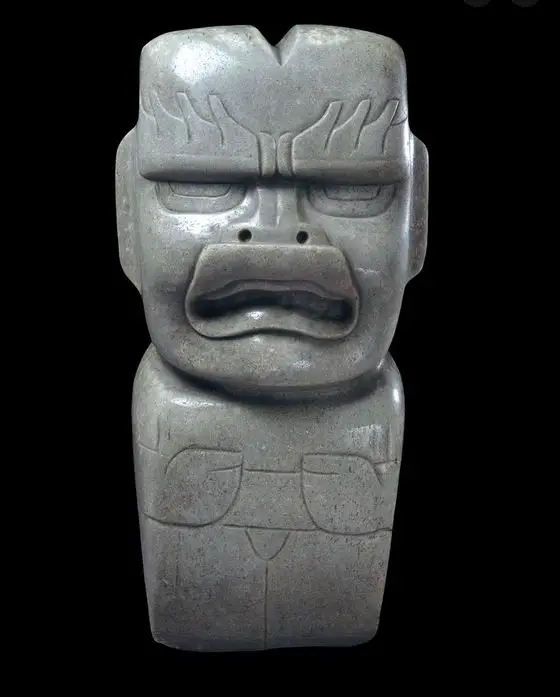

Perhaps the most amazing class of artifacts yet uncovered at El Manatí is the carved wooden heads which were thought to be old roots when they were first discovered by the villagers creating their fishponds. These carved heads are the earliest examples of wooden artifacts to have survived into modern times discovered in Mexico, and they date back to about 1200 BC. Just like ancient artifacts and human remains found in bogs in northern Europe, the stable temperature and specific conditions at the time of their burial halted the natural decay of these unique wooden artifacts. So far, 37 total carvings have been discovered. Made from wood from either the ceiba or hog plum trees, the sculptures have elongated faces much like distinct stone carvings and clay figurines found throughout the Olmec heartland. “Elongated faces” are not to be confused with “elongated skulls,” which are found in other parts of the world across various cultures. These carvings seem to be slight caricatures of what could have been real, living people with distinct personalities evident in their facial expressions. Each sculpture is unique, and while following a similar style, researchers agree that each sculpture was carved by a different set of hands. The carvings were ritually wrapped in mats made of vegetable fibers which may have represented some sort of shrouding or funerary wrapping. These amazing wooden sculptures were often associated with burials of the infant bones previously mentioned. Once again, archaeologists are not in agreement as to what these carvings represented. Were they depictions of ancestors? Were they rulers? Were they artistic renditions of water spirits or gods? Two of these carvings from El Manatí ended up in Germany in the mid-1990s by way of ancient artifact traffickers. They were being shown at a museum displaying the Bavarian State Archaeological Collection when a Mesoamerican scholar noticed them. After some delicate international diplomacy, the heads were repatriated to Mexico in 2018.

Perhaps the most amazing class of artifacts yet uncovered at El Manatí is the carved wooden heads which were thought to be old roots when they were first discovered by the villagers creating their fishponds. These carved heads are the earliest examples of wooden artifacts to have survived into modern times discovered in Mexico, and they date back to about 1200 BC. Just like ancient artifacts and human remains found in bogs in northern Europe, the stable temperature and specific conditions at the time of their burial halted the natural decay of these unique wooden artifacts. So far, 37 total carvings have been discovered. Made from wood from either the ceiba or hog plum trees, the sculptures have elongated faces much like distinct stone carvings and clay figurines found throughout the Olmec heartland. “Elongated faces” are not to be confused with “elongated skulls,” which are found in other parts of the world across various cultures. These carvings seem to be slight caricatures of what could have been real, living people with distinct personalities evident in their facial expressions. Each sculpture is unique, and while following a similar style, researchers agree that each sculpture was carved by a different set of hands. The carvings were ritually wrapped in mats made of vegetable fibers which may have represented some sort of shrouding or funerary wrapping. These amazing wooden sculptures were often associated with burials of the infant bones previously mentioned. Once again, archaeologists are not in agreement as to what these carvings represented. Were they depictions of ancestors? Were they rulers? Were they artistic renditions of water spirits or gods? Two of these carvings from El Manatí ended up in Germany in the mid-1990s by way of ancient artifact traffickers. They were being shown at a museum displaying the Bavarian State Archaeological Collection when a Mesoamerican scholar noticed them. After some delicate international diplomacy, the heads were repatriated to Mexico in 2018.

Research is ongoing at El Manatí and Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History has put a tight lid on this place. The site is not open to tourists, and may never be, so the people of the nearby village of El Macayal never realized the boon to their economy that they thought would result from bringing their precious artifacts to the attention of the authorities. Their discovery, however, to Mexico and to the rest of the world, is priceless.

REFERENCES

Grove, David C. “El Manatí: ‘Like Digging in Warm Jell-O’ (1987– 1993)”. Discovering the Olmecs: An Unconventional History, New York, USA: University of Texas Press, 2021, pp. 116-125.

Ortiz, Ponciano, and María del Carmen Rodríguez. “The Sacred Hill of El Manatí: A Preliminary Discussion of the Site’s Ritual Paraphernalia.” Studies in the History of Art, vol. 58, 2000, pp. 74–93.