Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In the realm of Maya archaeology, the names Stephens and Catherwood are legendary. The two Americans traveled together through the Yucatán and Central America in the 1840s and were oftentimes the first non-locals to explore ruined ancient cities. One such city was Kabah, located 87 miles south of Mérida, the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. While in a nearby town the two had heard of Kabah from a local and set off to find it. John Lloyd Stephens wrote detailed descriptions of his travels with Catherwood in a popular book at the time titled Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. He describes their approach to the ruins of Kabah on an old milpa or cornfield path. He writes:

In the realm of Maya archaeology, the names Stephens and Catherwood are legendary. The two Americans traveled together through the Yucatán and Central America in the 1840s and were oftentimes the first non-locals to explore ruined ancient cities. One such city was Kabah, located 87 miles south of Mérida, the capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán. While in a nearby town the two had heard of Kabah from a local and set off to find it. John Lloyd Stephens wrote detailed descriptions of his travels with Catherwood in a popular book at the time titled Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. He describes their approach to the ruins of Kabah on an old milpa or cornfield path. He writes:

“Following this path toward the field of ruins, the teocalis is the first object that meets the eye, grand, picturesque, ruined, and covered with trees like the House of the Dwarf at Uxmal towering above every other object on the plain. It is about 180 feet square at the base and rises in a pyramidal form to the height to 80 feet. At the foot is a range of ruined apartments. The steps are all fallen, and the sides present a surface of loose stones difficult to climb except on one side where the ascent is rendered practicably by the aid of a tree. The top presents a grand view. I ascended it for the first time toward evening, when the sun was about setting, and the ruined buildings were casting lengthened shadows over the plain. At the north South and east the view was bounded by a range of hills. In part of the field was a clearing, in which stood a deserted rancho, and the only indication that we were in the vicinity of man was the distant church in the village of Nohcacab.

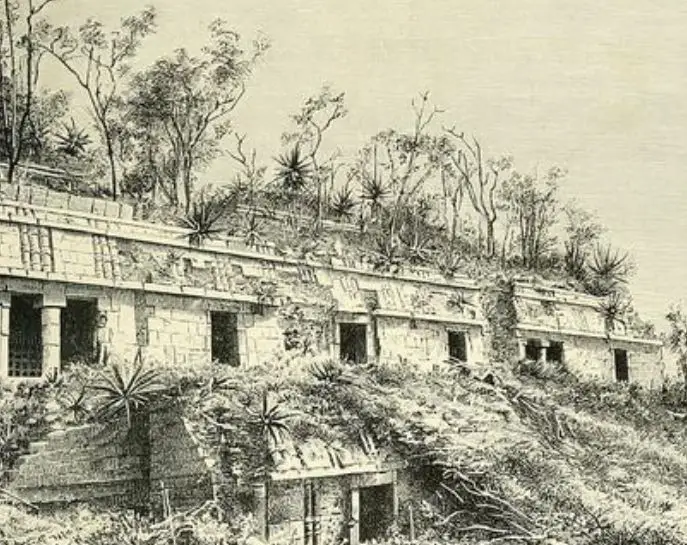

Leaving this mound, again taking the milpa path, and following it to the distance of three or four hundred yards, we reach the foot of a terrace twenty feet high, the edge of which is overgrown with trees; ascending this, we stand on a platform two hundred feet in width by one hundred and forty-two feet deep and facing us is the building represented in Plate XV. On the right of the platform, as we approach this building, is a high range of structures, ruined and overgrown with trees, with an immense back wall built on the outer line of the platform, perpendicular to the bottom of the terrace. On the left is another range of ruined buildings, not so grand as those on the right, and in the center of the platform is a stone enclosure twenty-seven feet square and seven feet high, like that surrounding the picote at Uxmal; but the layer of stones around the base was sculptured, and, on examination, we found a continuous line of hieroglyphics.”

“In the center of the platform is a range of stone steps forty feet wide and twenty in number, lending to an upper terrace, on which stands the building. This building is one hundred and fifty-one feet in front, and the moment we saw it we were struck with the extraordinary richness and ornament of its façade. In all the buildings of Uxmal, without a single exception, up to the cornice which runs over the doorway the façades are of plain stone: but this was ornamented from the very foundation, two layers under the lower cornice, to the top.”

“In the center of the platform is a range of stone steps forty feet wide and twenty in number, lending to an upper terrace, on which stands the building. This building is one hundred and fifty-one feet in front, and the moment we saw it we were struck with the extraordinary richness and ornament of its façade. In all the buildings of Uxmal, without a single exception, up to the cornice which runs over the doorway the façades are of plain stone: but this was ornamented from the very foundation, two layers under the lower cornice, to the top.”

In the last part Stephens was describing the Palace of the Masks, known in Yucatec Maya as the Codz Poop, which loosely translates to “Rolled Matting,” in English. This is due to the massive repetition of the stone mosaic designs on the face of the building that are interspersed between the hundreds of faces of the curled-nose rain god Chaac. Most would agree that this is quite possibly the most ornate and unique building in the entire Maya world. Each mask of Chaac on the outside wall of the palace is comprised of 30 carefully carved mosaic stones. Archaeologists have found evidence of copal incense in the noses of the stone Chaac masks. One can only imagine the ceremony and pageantry surrounding this building in the height of Kabah’s importance.

So, when exactly did this magnificent city flourish? The ancients started building at the site in the Third Century BC. The main flurry of monumental building at Kabah took place between 600 and 1000 AD with its apex around 900 AD. The oldest date thus found anyplace in the city reads a date of 987 AD. Kabah seemed to last a little longer than most other cities in the Yucatán through the Maya Collapse and no one knows exactly why. Kabah is one of the few ancient Maya sites whose modern name is the same as the name it called itself in its heyday. The name “Kabah” means “strong hand” in an older dialect of Maya. Some researchers suggest that the name was shortened and at one time the city called itself Kabahaucan which loosely translates to “royal snake in the hand.” There is a curious masculine male stone statue at the site – either a man or a deity – known to archaeologists as “M1.” This bold, muscular figure is clenching his fist, and this is believed to be a physical representation of the name of the site, either “Strong Hand” or “Royal Snake in Hand.” As with other Maya city states at the time, Kabah made war off and on with its neighbors, and valiant battles and the triumphs of Kabah’s kings are beautifully illustrated throughout the city on the sides of public monuments. At different times in its history, Kabah may have either been under the influence of or was directly controlled by Uxmal which is only some 15 miles to its northwest. For more information about this ancient Maya kingdom, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 181 titled, “Uxmal: Lost City of the Dwarf.” https://mexicounexplained.com/uxmal-lost-city-of-the-dwarf/ Archaeologists are a bit puzzled why people began building a settlement at the site of Kabah in the early centuries BC. There are few local resources to exploit and there is no reliable water source – no cenote or river – in the immediate vicinity. The lack of immediate ground or surface water was probably why there was such a big emphasis on the rain god Chaac at Kabah. The city, with a population numbering into the thousands at its height, was nearly 100% reliant on rainwater, and many water catchment systems were incorporated throughout the city that still exist today. A prolonged drought in the area may have led to the city’s abandonment and also may have had a hand in the overall collapse of the Maya civilization. Researchers are still trying to understand what happened here, but it is clear by around 1100 AD Kabah was abandoned.

So, when exactly did this magnificent city flourish? The ancients started building at the site in the Third Century BC. The main flurry of monumental building at Kabah took place between 600 and 1000 AD with its apex around 900 AD. The oldest date thus found anyplace in the city reads a date of 987 AD. Kabah seemed to last a little longer than most other cities in the Yucatán through the Maya Collapse and no one knows exactly why. Kabah is one of the few ancient Maya sites whose modern name is the same as the name it called itself in its heyday. The name “Kabah” means “strong hand” in an older dialect of Maya. Some researchers suggest that the name was shortened and at one time the city called itself Kabahaucan which loosely translates to “royal snake in the hand.” There is a curious masculine male stone statue at the site – either a man or a deity – known to archaeologists as “M1.” This bold, muscular figure is clenching his fist, and this is believed to be a physical representation of the name of the site, either “Strong Hand” or “Royal Snake in Hand.” As with other Maya city states at the time, Kabah made war off and on with its neighbors, and valiant battles and the triumphs of Kabah’s kings are beautifully illustrated throughout the city on the sides of public monuments. At different times in its history, Kabah may have either been under the influence of or was directly controlled by Uxmal which is only some 15 miles to its northwest. For more information about this ancient Maya kingdom, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode number 181 titled, “Uxmal: Lost City of the Dwarf.” https://mexicounexplained.com/uxmal-lost-city-of-the-dwarf/ Archaeologists are a bit puzzled why people began building a settlement at the site of Kabah in the early centuries BC. There are few local resources to exploit and there is no reliable water source – no cenote or river – in the immediate vicinity. The lack of immediate ground or surface water was probably why there was such a big emphasis on the rain god Chaac at Kabah. The city, with a population numbering into the thousands at its height, was nearly 100% reliant on rainwater, and many water catchment systems were incorporated throughout the city that still exist today. A prolonged drought in the area may have led to the city’s abandonment and also may have had a hand in the overall collapse of the Maya civilization. Researchers are still trying to understand what happened here, but it is clear by around 1100 AD Kabah was abandoned.

In addition to the three-tiered Palace of the Masks previously described, Kabah contains many other impressive structures and architectural elements. Most of the site was fashioned in what researchers call the Puuc style, common among the Classic Maya sites throughout the Puuc region of the Yucatán. Kabah also has some elements of the Chenes style which came later to the region. Two gigantic stone arches mark the entrances to the city. There are three main building clusters at Kabah. The Eastern Group contains the Palace of the Masks at its southern end. This group includes a plaza and in that plaza is what archaeologists call the Hieroglyphic Altar. This was briefly mentioned in the passage by John Lloyd Stephens. This altar, really a low platform structure, contains almost 150 stone blocks with ancient inscriptions detailing Kabah’s history. Because of the variety in styles, researchers believe that multiple artists created the Hieroglyphic Altar possibly over many decades. All the inscriptions have not yet been translated and may prove to be a treasure trove of information. The Northwest Group, sometimes called the North Group,  sits on a ridge which forms the highest point of the city. The structures of this group overlook Kabah to the east with direct view to the Palace of the Masks. These buildings were most likely reserved for members of the noble or priestly classes. Among these unrestored buildings is Kabah’s Great Pyramid. It is near this pyramid where the sacbe, or slightly raised stone causeway, begins that goes all the way to the city of Uxmal nearly 15 miles away. To the West of the Northwest Group is the appropriately named West Group, containing two clusters of buildings now undergoing restoration. On the wall of one of the structures of the West Group is a series of painted red hands of various sizes and hues. Scholars are baffled as to their meaning.

sits on a ridge which forms the highest point of the city. The structures of this group overlook Kabah to the east with direct view to the Palace of the Masks. These buildings were most likely reserved for members of the noble or priestly classes. Among these unrestored buildings is Kabah’s Great Pyramid. It is near this pyramid where the sacbe, or slightly raised stone causeway, begins that goes all the way to the city of Uxmal nearly 15 miles away. To the West of the Northwest Group is the appropriately named West Group, containing two clusters of buildings now undergoing restoration. On the wall of one of the structures of the West Group is a series of painted red hands of various sizes and hues. Scholars are baffled as to their meaning.

Stephens and Catherwood noted something exceptional at Kabah that deserves special attention. When they arrived and started clearing the vegetation at the site, they discovered several large wooden door jambs and lintels that were completely intact and elaborately carved. The 2 Americans were astonished to see massive wooden items like these that had survived the many centuries of exposure to the elements. The  explorers removed some of these beautifully carved wooden pieces and others were whisked away by later collectors and museum procurers. Many are now lost or have become damaged in the care of others. Archaeologists today are as amazed as Stephens and Catherwood were at how these hardwood pieces were carved with rudimentary stone tools.

explorers removed some of these beautifully carved wooden pieces and others were whisked away by later collectors and museum procurers. Many are now lost or have become damaged in the care of others. Archaeologists today are as amazed as Stephens and Catherwood were at how these hardwood pieces were carved with rudimentary stone tools.

Kabah was declared a Yucatán State Park in 1993, and at that time only a fraction of the city had been cleared of forest growth. Even though serious restoration of the site began in the year 2003, most of Kabah is still unexplored and overgrown with only the East Group – home to the Palace of the Masks – fully open to tourists. With much exploration and research still to be done here, Kabah has yet to reveal its many untold secrets.

REFERENCES

Stephens, John L. Incidents of Travel in Yucatan. New York: Dover Publications, 1963. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3HlVSmM

Wikipedia