Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

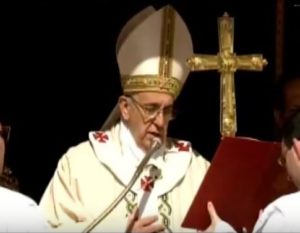

It was a sunny spring day in Rome. The date was Sunday, May 12, 2013. Pope Francis had been head of the Catholic Church for only a month and was already participating in a canonization ceremony which had been scheduled months before by his predecessor, Pope Benedict the Sixteenth. The Argentine pope scanned the crowd at Saint Peter’s Square and noticed many humble looking people clad in bright sarapes and indigenous dress alongside nuns wearing the crisp white habits of their order which seemed to radiate their own light in the midday Italian sun. The sisters and colorfully attired Mexicans had made the long journey to Rome to witness one of their own made into a saint, a nun who lived an extraordinary life, a woman born Anastasia Guadalupe García Zavala, in the Guadalajara suburb of Zapopan in 1878. “Madre Lupita,” as she was also known, would share the stage that day with many others whom the pope would declare saints: a Colombian woman who set up jungle missionaries to minister to the indigenous, and the 800 Martyrs of Otranto, a group who died at the hands of Ottoman invaders of the Italian town of Otranto in 1480, choosing death by beheading instead of a forced mass conversion to Islam. While the ceremonies surrounding the proclamations of saints can sometimes be solemn affairs, the Mexicans in Saint Peter’s Square that day felt a light sense of joy in their hearts upon seeing Madre Lupita getting the recognition she deserved. By the end of the day the Mexicans had their second female saint: Saint María Guadalupe García Zavala, Angel to the Poor.

It was a sunny spring day in Rome. The date was Sunday, May 12, 2013. Pope Francis had been head of the Catholic Church for only a month and was already participating in a canonization ceremony which had been scheduled months before by his predecessor, Pope Benedict the Sixteenth. The Argentine pope scanned the crowd at Saint Peter’s Square and noticed many humble looking people clad in bright sarapes and indigenous dress alongside nuns wearing the crisp white habits of their order which seemed to radiate their own light in the midday Italian sun. The sisters and colorfully attired Mexicans had made the long journey to Rome to witness one of their own made into a saint, a nun who lived an extraordinary life, a woman born Anastasia Guadalupe García Zavala, in the Guadalajara suburb of Zapopan in 1878. “Madre Lupita,” as she was also known, would share the stage that day with many others whom the pope would declare saints: a Colombian woman who set up jungle missionaries to minister to the indigenous, and the 800 Martyrs of Otranto, a group who died at the hands of Ottoman invaders of the Italian town of Otranto in 1480, choosing death by beheading instead of a forced mass conversion to Islam. While the ceremonies surrounding the proclamations of saints can sometimes be solemn affairs, the Mexicans in Saint Peter’s Square that day felt a light sense of joy in their hearts upon seeing Madre Lupita getting the recognition she deserved. By the end of the day the Mexicans had their second female saint: Saint María Guadalupe García Zavala, Angel to the Poor.

The future saint was born to an upper-middle-class merchant family in the state of Jalisco on April 27, 1878. She was named Anastasia, but went by María, one of the names assigned to her at her christening. María’s father, Fortino García, owned a store selling religious merchandise located next to the Cathedral of Zapopan, now the Basilica of Our Lady of Zapopan. Please see Mexico Unexplained Episode #56 to learn more about the Virgin of Zapopan. As a young girl, María would accompany her father to the family’s religious goods store and would always stop into the cathedral to pray to the Virgin there or to take contemplative walks on the cathedral’s grounds. María’s daily visits to one of the most visited Catholic shrines in Mexico exposed her to many aspects of humanity. People came to the shrine to pray out of desperation for a loved one or for an impossible situation. The extremely poor, the handicapped, or indigenous people newly arrived from the countryside were regular fixtures at the front steps of the building, begging for assistance and hoping for miracles. María witnessed the extremes of generosity and poverty on a daily basis and what she experienced would influence her for the rest of her life. No one else in the García family had the enthusiasm for visiting the cathedral as did the young María, and she became known for her devotion and deep faith, even at a young age. Through her adolescence she maintained her religious devotions and grew into a beautiful young woman. At age 23, María was engaged to a handsome up-and-coming young businessman named Gustavo Arreola. At a dance, right before she was to be married, she called off the engagement and told Gustavo that she had a different calling and wanted to pursue a life of religious devotion. It was at this point when María contacted her spiritual advisor, Father Cipriano Iñiguez and talked to him about her change of plans and told him of a strong urge she had for service within a religious order. Father Iñiguez told María that for the longest time he wanted to establish an order to help in hospitals to tend to the sick and dying. After months of planning together, on October 13, 1901, Father Iñiguez and María García Zavala founded a new order officially named The Congregation of the Handmaids of Saint Margaret Mary and the Poor. The patroness of the congregation, Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque, was a 17th Century French nun who was part of the order of The Poor Ladies, Sisters of Saint Clare, known informally as The Poor Clares.

The future saint was born to an upper-middle-class merchant family in the state of Jalisco on April 27, 1878. She was named Anastasia, but went by María, one of the names assigned to her at her christening. María’s father, Fortino García, owned a store selling religious merchandise located next to the Cathedral of Zapopan, now the Basilica of Our Lady of Zapopan. Please see Mexico Unexplained Episode #56 to learn more about the Virgin of Zapopan. As a young girl, María would accompany her father to the family’s religious goods store and would always stop into the cathedral to pray to the Virgin there or to take contemplative walks on the cathedral’s grounds. María’s daily visits to one of the most visited Catholic shrines in Mexico exposed her to many aspects of humanity. People came to the shrine to pray out of desperation for a loved one or for an impossible situation. The extremely poor, the handicapped, or indigenous people newly arrived from the countryside were regular fixtures at the front steps of the building, begging for assistance and hoping for miracles. María witnessed the extremes of generosity and poverty on a daily basis and what she experienced would influence her for the rest of her life. No one else in the García family had the enthusiasm for visiting the cathedral as did the young María, and she became known for her devotion and deep faith, even at a young age. Through her adolescence she maintained her religious devotions and grew into a beautiful young woman. At age 23, María was engaged to a handsome up-and-coming young businessman named Gustavo Arreola. At a dance, right before she was to be married, she called off the engagement and told Gustavo that she had a different calling and wanted to pursue a life of religious devotion. It was at this point when María contacted her spiritual advisor, Father Cipriano Iñiguez and talked to him about her change of plans and told him of a strong urge she had for service within a religious order. Father Iñiguez told María that for the longest time he wanted to establish an order to help in hospitals to tend to the sick and dying. After months of planning together, on October 13, 1901, Father Iñiguez and María García Zavala founded a new order officially named The Congregation of the Handmaids of Saint Margaret Mary and the Poor. The patroness of the congregation, Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque, was a 17th Century French nun who was part of the order of The Poor Ladies, Sisters of Saint Clare, known informally as The Poor Clares.

From the patron saint of the order Sister María drew her example of living a simple and humble existence. She joyfully embraced poverty and was often heard saying, “Be poor with the poor,” while ministering to the sick and needy. In the early days of the new order, María worked out of a small run-down building that served as their hospital. She welcomed patients who had no money to pay for their care and tended to them both physically and spiritually. As news of her good works spread, more young women showed interest in joining the Handmaids. Father Iñiguez soon made María the Superior General of the order and she was thereafter known as “Madre Lupita.” True to her motto, “Be poor with the poor,” Madre Lupita and her sisters would often beg on the street to raise funds for their medical facilities. The sisters would retire to the hospital when the basic needs of the facilities were met and didn’t ask of others any more than they needed. As the Handmaids of Saint Mary Margaret and the Poor grew, they expanded their reach out of their hospital and into the community, often working in the local parishes to teach catechism classes or to assist with elderly or sick parishioners.

From the patron saint of the order Sister María drew her example of living a simple and humble existence. She joyfully embraced poverty and was often heard saying, “Be poor with the poor,” while ministering to the sick and needy. In the early days of the new order, María worked out of a small run-down building that served as their hospital. She welcomed patients who had no money to pay for their care and tended to them both physically and spiritually. As news of her good works spread, more young women showed interest in joining the Handmaids. Father Iñiguez soon made María the Superior General of the order and she was thereafter known as “Madre Lupita.” True to her motto, “Be poor with the poor,” Madre Lupita and her sisters would often beg on the street to raise funds for their medical facilities. The sisters would retire to the hospital when the basic needs of the facilities were met and didn’t ask of others any more than they needed. As the Handmaids of Saint Mary Margaret and the Poor grew, they expanded their reach out of their hospital and into the community, often working in the local parishes to teach catechism classes or to assist with elderly or sick parishioners.

By 1911, with Madre Lupita’s order financially stable and things finally looking up for the sisters, the political situation in Mexico changed for the worse. There was much uncertainty in the early days of the Mexican Revolution, especially with regard to the status of the Catholic Church. For most of Mexico’s history there has existed a struggle between secular and clerical power. The government historically had always sought to limit the power of the Church and throughout the 19th Century the Church was subject to halfhearted attempts to limit its power and wealth. By the beginning of the 20th Century, those who overthrew the old order ruling Mexico wanted to have a much stricter control over church authority and many restrictive provisions were written into the new constitution. Church and state relations remained uneasy at best until the Cristero War in the 1920s. Madre Lupita found herself in the middle of this brutal conflict also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada, which lasted between 1926 and 1929 and pitted Catholic lay people and clergymen against the forces of the anti-Catholic, anti-clerical central government in Mexico City headed by President  Plutarco Calles. Calles sought to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the new Constitution of 1917. Under these laws restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. As a consequence, Madre Lupita and the Handmaids gave up wearing the nun’s habit and dressed as modest laypeople, but continued their hospital work unabated. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacán. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. During the Cristero War, Madre Lupita did two things of note. She sheltered “rebel” priests in her hospital facilities, including the Mexican government’s most wanted man, the Archbishop of Guadalajara, Francisco Orozco y Jiménez. Madre Lupita, as a consummate humanitarian, also did not take sides in the fight; she opened up her hospital facilities to everyone and even treated injured and dying government soldiers who had fought against the Catholic Church. It was this gesture – of welcoming and treating anyone in need – that afforded her the protection of the local government garrison which should have been her sworn enemy. By 1928, the Cristero War ended and hundreds of thousands of people were dead on both sides. Madre Lupita’s order emerged from the conflict even stronger than before. In the 1930s and 1940s the order expanded throughout Mexico and ministered to the poor and helpless in the most desperate areas of the country. Nuns continued to live in the new convents as per Madre Lupita’s motto, “Be poor with the poor,” with an emphasis on tireless, compassionate care for those in most need.

Plutarco Calles. Calles sought to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the new Constitution of 1917. Under these laws restrictions were placed on the Catholic clergy and the power of the Church was further limited. Popular religious celebrations were suppressed in local communities along with the number of priests allowed to serve in Mexico as a whole. As a consequence, Madre Lupita and the Handmaids gave up wearing the nun’s habit and dressed as modest laypeople, but continued their hospital work unabated. A few uprisings happened in 1926 and full-scale violence ensued by 1927, most notably in the countryside of the states of Zacatecas, Jalisco and Michoacán. Most clergy did not take part in violence, although many defied the authorities and continued performing Catholic rites. The Church hierarchy in Mexico tacitly supported the grassroots rebellion and the authorities in Rome condemned the Mexican government. During the Cristero War, Madre Lupita did two things of note. She sheltered “rebel” priests in her hospital facilities, including the Mexican government’s most wanted man, the Archbishop of Guadalajara, Francisco Orozco y Jiménez. Madre Lupita, as a consummate humanitarian, also did not take sides in the fight; she opened up her hospital facilities to everyone and even treated injured and dying government soldiers who had fought against the Catholic Church. It was this gesture – of welcoming and treating anyone in need – that afforded her the protection of the local government garrison which should have been her sworn enemy. By 1928, the Cristero War ended and hundreds of thousands of people were dead on both sides. Madre Lupita’s order emerged from the conflict even stronger than before. In the 1930s and 1940s the order expanded throughout Mexico and ministered to the poor and helpless in the most desperate areas of the country. Nuns continued to live in the new convents as per Madre Lupita’s motto, “Be poor with the poor,” with an emphasis on tireless, compassionate care for those in most need.

After a 2-year illness, Madre Lupita passed away on June 24, 1963 at the age of 85. In her 6 decades of service to the underserved, she helped hundreds of thousands of people. At the time of Madre Lupita’s death, her order operated 11 facilities throughout Mexico. By 2017 that number has doubled and has expanded to countries outside of Mexico. The Handmaids of Saint Margaret Mary and the Poor now have hospitals in Peru, Italy, Greece and even Iceland.

After a 2-year illness, Madre Lupita passed away on June 24, 1963 at the age of 85. In her 6 decades of service to the underserved, she helped hundreds of thousands of people. At the time of Madre Lupita’s death, her order operated 11 facilities throughout Mexico. By 2017 that number has doubled and has expanded to countries outside of Mexico. The Handmaids of Saint Margaret Mary and the Poor now have hospitals in Peru, Italy, Greece and even Iceland.

Soon after Madre Lupita’s death, people who prayed to her had claimed actually to have experienced the spirit of Madre Lupita or had a visit from her. A patient in one of the Handmaids’ facilities named Abraham Arceo Higaresa who had suffered from pacreatitis was one such person. After intense prayer to Madre Lupita for her help in curing him, Abraham reported smelling a sweet fragrance and then felt 100% better. He astounded doctors by being completely healed. This was one of the two required miracles needed for Madre Lupita’s promotion to sainthood. The miracle was reviewed by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and approved after a lengthy process by Pope John Paul the Second on December 20, 2003. In a ceremony in Saint Peter’s Square on April 25, 2004, the pope pronounced Madre Lupita “beatified,” which is the last stop before canonization. To a large crowd, Pope John Paul the Second declared:

“With deep faith, unlimited hope, and great love for Christ, Mother ‘Lupita’ sought her own sanctification beginning with the love for the Heart of Christ and fidelity to the Church. In this way she lived the motto which she left to her daughters: ‘Charity to the point of sacrifice and perseverance until death’.”

“With deep faith, unlimited hope, and great love for Christ, Mother ‘Lupita’ sought her own sanctification beginning with the love for the Heart of Christ and fidelity to the Church. In this way she lived the motto which she left to her daughters: ‘Charity to the point of sacrifice and perseverance until death’.”

Today, Saint María Guadalupe García Zavala enjoys great veneration throughout Mexico and her popularity is growing especially among the youth of Mexico who look upon her as a grandmotherly figure. Many more miracles are ascribed to her intercession and many people throughout Mexico continue to be inspired by her example of piety, sacrifice and dedication to those most in need.

REFERENCES (This is not a formal bibliography)

“Saint María Guadalupe García Zavala,” in Our Sunday Visitor, 15 May 2013.

“Catholic Heroes… Mother María Guadalupe García Zavala,” by Carole Breslin, in The Wanderer

21 June 2016

Wikipedia

3 thoughts on “Madre Lupita, Mexican Saint & Angel to the Poor”

Today mother Lupita appeared to me at a Spanish catholic mass and told me she would “guide” my 80 year old mother in this life remaining and into the next. I didn’t know who the Mexican woman was, dark eyes grey hair cut shorter with bangs cut and to the side, her calm demeanor was comforting. She was dressed in a traditional Mexican dress, green with multicolored flowers across the front. She said her name was “Lupita” or Lupe. I thanked her for taking over this guidance of my mother for me, as she said “in this life and on into the next”. When I got home from church I googled any Catholic saints with that name and found her. Looking closely at her face I think this is her she did not wear a habit but traditional Mexican dress. I read that the nuns gave up their habits because of the political turmoil and adopted the traditional Mexican dress to continue their hospital work. Madre Lupita is the patron saint of nurses. My mom ther was a nurse most of her life beginning in her early 20s until her mid 70s. I was comforted by this message and believe I can rest easy now knowing my mother is in her care.

Thank you very much for sharing your story with us here.

I I am an Oblateof Saint Francis DeSales And have worked in Merida Yucatán for 30 years with the maya.. I enjoyed reading about the feast of Saint Maria Guadalupe and her connection with stSaint Margaret Mary. I would like to know more about the connection between Saint Margaret Mary and Saint Maria Guadalupe.