Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

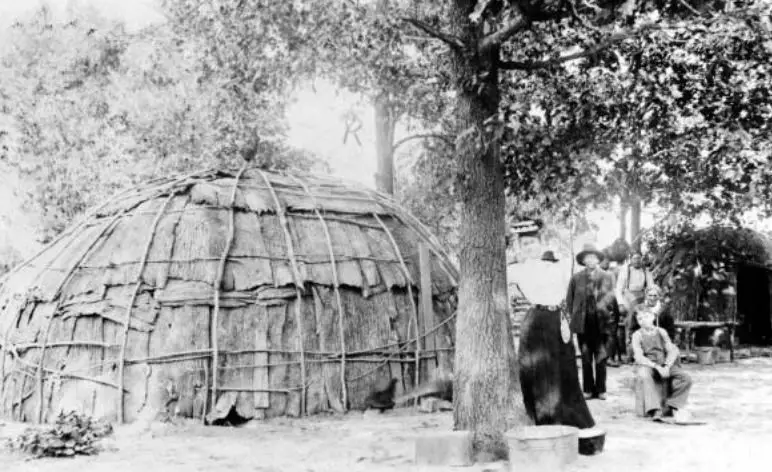

In the late 1940s, people using the border crossing linking Piedras Negras, Coahuila and Eagle Pass, Texas, beheld a curious sight under the bridge on the small floodplain of the Rio Grande on the American side. A small cluster of dome-like shacks numbering no more than two dozen or so, seemed to huddle under the international bridge and served as makeshift dwellings for a dejected people who were struggling to survive. These rounded shacks were made of bent branches of young trees, old plywood, and pieces of tarp and plastic. Some who made the crossing daily from Piedras Negras to Eagle Pass and back would hurl insults and throw trash at the squatters below. Others reacted with curiosity as they had never seen a shanty town full of rounded houses before. Little did they know they were looking at wikiups, and the ancestors of the people making them originally lived south of Lake Erie some 1,600 miles away. Passersby were also not aware that they were witnessing just a small part of one of the most incredible tales of indigenous survival and perseverance in the history of North America. After spending some four generations in Mexico, these members of a forgotten band of Kickapoo people found themselves north of the Rio Grande once again, albeit reluctantly.

In the late 1940s, people using the border crossing linking Piedras Negras, Coahuila and Eagle Pass, Texas, beheld a curious sight under the bridge on the small floodplain of the Rio Grande on the American side. A small cluster of dome-like shacks numbering no more than two dozen or so, seemed to huddle under the international bridge and served as makeshift dwellings for a dejected people who were struggling to survive. These rounded shacks were made of bent branches of young trees, old plywood, and pieces of tarp and plastic. Some who made the crossing daily from Piedras Negras to Eagle Pass and back would hurl insults and throw trash at the squatters below. Others reacted with curiosity as they had never seen a shanty town full of rounded houses before. Little did they know they were looking at wikiups, and the ancestors of the people making them originally lived south of Lake Erie some 1,600 miles away. Passersby were also not aware that they were witnessing just a small part of one of the most incredible tales of indigenous survival and perseverance in the history of North America. After spending some four generations in Mexico, these members of a forgotten band of Kickapoo people found themselves north of the Rio Grande once again, albeit reluctantly.

The Kickapoo were living in the southern Great Lakes area at the time of first European contact in the 1660s. French fur traders first encountered this people who called themselves the Kiwigapawa, which loosely translates into English as “Those who move from place to place,” or “The Wanderers.” The Kickapoo language is Algonquian and is related to some of the other languages spoken by indigenous people found at the time around the Great Lakes and Eastern Woodlands, such as Fox, Sauk and Shawnee. By the first few years of the 1800s the Kickapoo were already having run-ins with settlers from the fledgling United States. Their first treaty with the US was signed on June 7, 1803, which granted the Kickapoo land and hunting rights. There were 5 more treaties with the American government which eventually led to the Kickapoo relocating to a reservation in southwestern Missouri. That reservation lasted from 1820 to 1832 when the Kickapoo were moved on their own request to another reservation near Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The move was sparked by constant conflicts with American settlers squatting on their federally recognized tribal lands and the overall increase of American settler presence in southwestern Missouri. In the early 1830s many Kickapoos on the Kansas reservation were granted lands by the Mexican government to settle in Texas to serve as a buffer against other more warlike indigenous groups and American expansionism in the region. By the time of the Texas Revolution there were several hundred Kickapoos living in Texas. When Texas became independent, the new republic proclaimed all Indians living within its boundaries as hostile. The political solution was to drive all indigenous people out of Texas territory and kill those who resisted. This caused a mass migration of natives north across the Canadian River into Oklahoma including several hundred Kickapoos who were granted lands in Texas by the Mexican government just a few years before. While in Oklahoma, the former Texas Kickapoos met up with  Coacoochee, also known as Wild Cat, a celebrated Seminole leader who had been relocated to what was then known as Indian Territory. Coacoochee listened to the stories of the Kickapoos’ fair treatment under Mexican rule and had the idea to relocate some of his people to lands across the Rio Grande in Mexico. Under Coacoochee’s leadership, a few hundred Kickapoos and just a few dozen Seminoles made the dangerous trek through the enemy territory of Texas and arrived in the Mexican state of Coahuila in early 1848. Within a year, most of the Seminoles returned to Oklahoma while most of the Kickapoos decided to stay in Mexico. In 1850, a delegation of Kickapoo went to Mexico City endeavoring to obtain a gift of land on which to establish a permanent settlement. After a few weeks of negotiation, the Mexican government granted the Kickapoos a 17,000-acre tract of land which is still occupied by their descendants near the town of Santa Rosa, now called Muzquiz. The land grant was called the Hacienda del Nacimiento and is sometimes referred to the Ranchería del Nacimiento in official Mexican documents and histories. In exchange for the land, the Kickapoos agreed to help the Mexicans fight off Comanche and Apache raiding parties that were terrorizing northern Mexico at the time. For more information about the Mexican government’s wars with the Comanche and Apache peoples, please see Mexico Unexplained episodes number 212 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-comanche-wars-1821-1870/ and 277 https://mexicounexplained.com/apache-wars-with-mexico/. The Kickapoos of Nacimiento held up their end of the bargain and their community flourished. In the 1860s with a increase in the town’s population some groups of Kickapoos relocated to the Mexican states of Sonora and Durango where they established small farming settlements. The increase in population was not only from a higher birthrate among the Kickapoo settlers of Nacimiento but from immigration. In 1862, a group of a few dozen Kickapoos crossed the Rio Grande to avoid being caught in the crossfire of the Civil War and integrated peacefully into the community established by their Kickapoo cousins in Mexico. Word of this Kickapoo utopia at the edge of the Sierra Madre spread throughout Indian Country in the US and in September of 1864, some 700 Kickapoos from the Kansas reservation left to join the Mexican Kickapoos after enduring years of harassment by American settlers, the US government, and the railroads. While on their way through Texas, the group encountered an unexpected hostile force to impede them: The Confederate Army. Near present-day San Angelo, Texas, a half-hour battle ensued between the boys in gray and the natives during which 15 Kickapoos died. The Confederates lost twice as many men and eventually let the Kickapoos go on their way and pass through Texas.

Coacoochee, also known as Wild Cat, a celebrated Seminole leader who had been relocated to what was then known as Indian Territory. Coacoochee listened to the stories of the Kickapoos’ fair treatment under Mexican rule and had the idea to relocate some of his people to lands across the Rio Grande in Mexico. Under Coacoochee’s leadership, a few hundred Kickapoos and just a few dozen Seminoles made the dangerous trek through the enemy territory of Texas and arrived in the Mexican state of Coahuila in early 1848. Within a year, most of the Seminoles returned to Oklahoma while most of the Kickapoos decided to stay in Mexico. In 1850, a delegation of Kickapoo went to Mexico City endeavoring to obtain a gift of land on which to establish a permanent settlement. After a few weeks of negotiation, the Mexican government granted the Kickapoos a 17,000-acre tract of land which is still occupied by their descendants near the town of Santa Rosa, now called Muzquiz. The land grant was called the Hacienda del Nacimiento and is sometimes referred to the Ranchería del Nacimiento in official Mexican documents and histories. In exchange for the land, the Kickapoos agreed to help the Mexicans fight off Comanche and Apache raiding parties that were terrorizing northern Mexico at the time. For more information about the Mexican government’s wars with the Comanche and Apache peoples, please see Mexico Unexplained episodes number 212 https://mexicounexplained.com/the-comanche-wars-1821-1870/ and 277 https://mexicounexplained.com/apache-wars-with-mexico/. The Kickapoos of Nacimiento held up their end of the bargain and their community flourished. In the 1860s with a increase in the town’s population some groups of Kickapoos relocated to the Mexican states of Sonora and Durango where they established small farming settlements. The increase in population was not only from a higher birthrate among the Kickapoo settlers of Nacimiento but from immigration. In 1862, a group of a few dozen Kickapoos crossed the Rio Grande to avoid being caught in the crossfire of the Civil War and integrated peacefully into the community established by their Kickapoo cousins in Mexico. Word of this Kickapoo utopia at the edge of the Sierra Madre spread throughout Indian Country in the US and in September of 1864, some 700 Kickapoos from the Kansas reservation left to join the Mexican Kickapoos after enduring years of harassment by American settlers, the US government, and the railroads. While on their way through Texas, the group encountered an unexpected hostile force to impede them: The Confederate Army. Near present-day San Angelo, Texas, a half-hour battle ensued between the boys in gray and the natives during which 15 Kickapoos died. The Confederates lost twice as many men and eventually let the Kickapoos go on their way and pass through Texas.

In Mexico, left alone by government authorities and encroaching land and business interests, the Kickapoo thrived. It was estimated that they numbered about 1,200 people by the year 1870. Perhaps with American mistreatment still in their minds, by the early 1870s the Mexican Kickapoo began crossing into Texas and started raiding, much like the Comanche and the Apache, capturing horses and cattle from Texas ranches and causing property destruction in their wake. Crossing the international line back into Mexico was safe for the Kickapoos for a while, until 1873 when US Army Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie decided to disregard international law. Colonel Mackenzie pursued the Kickapoos all the way back to their ranchería at Nacimiento. The colonel killed over a hundred people and burned down most everything in the well-established indigenous settlement. Some Kickapoo leaders were taken back across the Rio Grande into Texas to be tried and imprisoned. Later that same year, 1873, a civilian commission went to Nacimiento to try to convince tribal members to relocate to the United States. Many people from Nacimiento – some of whom were born in Mexico and had never even set foot on US soil – agreed to be relocated to Indian Territory, which would later become Oklahoma. The next year, 1874, an entire Kickapoo settlement that had been established in Chihuahua decided to disband and move to what was promised to be a better life across the Rio Grande. The Chihuahua group split between Indian Territory and the Kansas Kickapoo reservation. Only about 500 Kickapoos remained in Mexico, most under close watch living in the village at Nacimiento. The Mexican Kickapoo ceased all raiding and went back to a peaceful existence on their land grant. In 1878, yet another group of Kickapoo from the US decided to make the move to join their brethren across the Rio Grande. This time it was because many tribal members had been defrauded of their land allotments guaranteed by the US government by treaty, and they knew of the independence they would have if they went south to join up with the Mexican Kickapoo. This new group of about 80 people tried settling lands near Nacimiento but were not welcomed by Mexican authorities. The Mexican government offered them a miserable piece of land in Coahuila far away from Nacimiento and the group refused. Half of this group of 80 went back to Kansas and the other half went west to Chihuahua. In the 1880s the US government again tried to repatriate all Kickapoos from Mexico with promises of tracts of land and farm equipment. Some left to relocate in Indian Territory, but the majority remained.

In Mexico, left alone by government authorities and encroaching land and business interests, the Kickapoo thrived. It was estimated that they numbered about 1,200 people by the year 1870. Perhaps with American mistreatment still in their minds, by the early 1870s the Mexican Kickapoo began crossing into Texas and started raiding, much like the Comanche and the Apache, capturing horses and cattle from Texas ranches and causing property destruction in their wake. Crossing the international line back into Mexico was safe for the Kickapoos for a while, until 1873 when US Army Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie decided to disregard international law. Colonel Mackenzie pursued the Kickapoos all the way back to their ranchería at Nacimiento. The colonel killed over a hundred people and burned down most everything in the well-established indigenous settlement. Some Kickapoo leaders were taken back across the Rio Grande into Texas to be tried and imprisoned. Later that same year, 1873, a civilian commission went to Nacimiento to try to convince tribal members to relocate to the United States. Many people from Nacimiento – some of whom were born in Mexico and had never even set foot on US soil – agreed to be relocated to Indian Territory, which would later become Oklahoma. The next year, 1874, an entire Kickapoo settlement that had been established in Chihuahua decided to disband and move to what was promised to be a better life across the Rio Grande. The Chihuahua group split between Indian Territory and the Kansas Kickapoo reservation. Only about 500 Kickapoos remained in Mexico, most under close watch living in the village at Nacimiento. The Mexican Kickapoo ceased all raiding and went back to a peaceful existence on their land grant. In 1878, yet another group of Kickapoo from the US decided to make the move to join their brethren across the Rio Grande. This time it was because many tribal members had been defrauded of their land allotments guaranteed by the US government by treaty, and they knew of the independence they would have if they went south to join up with the Mexican Kickapoo. This new group of about 80 people tried settling lands near Nacimiento but were not welcomed by Mexican authorities. The Mexican government offered them a miserable piece of land in Coahuila far away from Nacimiento and the group refused. Half of this group of 80 went back to Kansas and the other half went west to Chihuahua. In the 1880s the US government again tried to repatriate all Kickapoos from Mexico with promises of tracts of land and farm equipment. Some left to relocate in Indian Territory, but the majority remained.

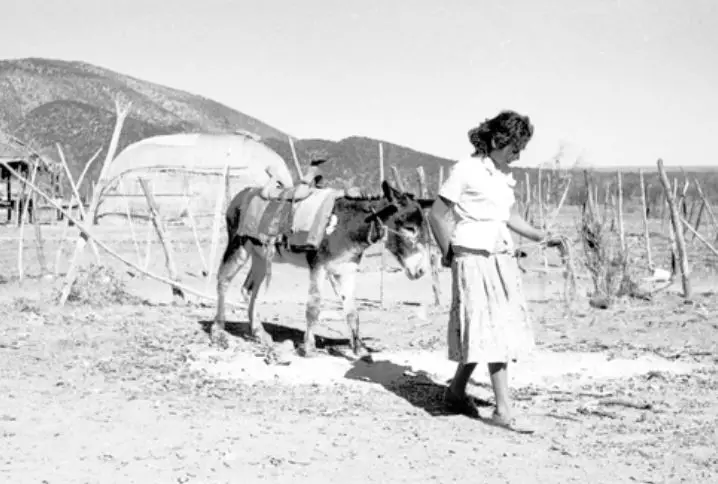

From the 1890s to the 1940s the Mexican Kickapoo lived in relative isolation but had intermittent contact with their counterparts in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. While the Kickapoos in the States slowly became modernized, living an existence somewhat disconnected from the outside world allowed the Mexican branch of the Kickapoo to preserve their culture and language much as it had existed when they lived in their ancestral homeland around the Great Lakes.

As a curious aside, part of Kickapoo culture that survived in Mexico but not in the United States is what anthropologists call the Kickapoo “Whistled Speech.” According to Robert E. Ritzenthaler and Frederick A. Peterson in their 1954 article published in American Anthropologist about this form of communication, entire conversations can take place between people in whistles approximating the pitch, accent, and cadence of the Kickapoo language. According to the authors in the article:

“The hands are cupped, and air blown into the cavity between the knuckles of the thumbs placed against the lips vertically. Three fingers of the right hand are cupped so that the ends rest near the base of the index finger of the left hand. The fingers of the left hand control the aperture at the back of the hand, opening and closing to further control the tone produced by the oral cavity and the lips.”

What changed the world of the Mexican Kickapoos forever was a 7-year drought that began in 1946 which caused them to migrate north of the Rio Grande to look for seasonal agricultural work. The wikiup encampment under the bridge at Eagle Pass was the product of the Mexican Kickapoo drought exodus. Some who left for work in the US during this time never returned to Nacimiento. Some stayed in the Eagle Pass area and would later form what is now known as the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. The Texas branch of Mexican Kickapoo would get federal recognition from the US government in 1983 and in 1985 all borderland Kickapoo were given the option of US or Mexican citizenship. 145 tribal members decided to become US citizens and some 500 remained citizens of Mexico. A few miles south of the site of the former wikiup shantytown under the international bridge, The Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas was granted 118 acres of land for a reservation where the multi-million-dollar Lucky Eagle Casino now stands. Meanwhile in Mexico, less than 75 Kickapoos currently live in the town of Nacimiento. With help from the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City there is a race to preserve the language and culture of the Mexican Kickapoo but some fear this very unique culture will not last two more generations on Mexican soil. Time will tell.

What changed the world of the Mexican Kickapoos forever was a 7-year drought that began in 1946 which caused them to migrate north of the Rio Grande to look for seasonal agricultural work. The wikiup encampment under the bridge at Eagle Pass was the product of the Mexican Kickapoo drought exodus. Some who left for work in the US during this time never returned to Nacimiento. Some stayed in the Eagle Pass area and would later form what is now known as the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas. The Texas branch of Mexican Kickapoo would get federal recognition from the US government in 1983 and in 1985 all borderland Kickapoo were given the option of US or Mexican citizenship. 145 tribal members decided to become US citizens and some 500 remained citizens of Mexico. A few miles south of the site of the former wikiup shantytown under the international bridge, The Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas was granted 118 acres of land for a reservation where the multi-million-dollar Lucky Eagle Casino now stands. Meanwhile in Mexico, less than 75 Kickapoos currently live in the town of Nacimiento. With help from the National Institute of Anthropology and History out of Mexico City there is a race to preserve the language and culture of the Mexican Kickapoo but some fear this very unique culture will not last two more generations on Mexican soil. Time will tell.

REFERENCES

Delatorre, Felipe A. and Dolores L. Delatorre. The Mexican Kickapoo Indians. New York: Dover Publications, 1991. We are Amazon affiliates. To buy the book on Amazon click here: https://amzn.to/3t3mfK9

Goggin, John M. “The Mexican Kickapoo Indians.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 7, no. 3 (1951): 314–27.

Ritzenthaler, Robert E., and Frederick A. Peterson. “Courtship Whistling of the Mexican Kickapoo Indians.” American Anthropologist 56, no. 6 (1954): 1088–89.

Website of the Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas: https://kickapootexas.org/