The year was 1889. The place was a rancho between the Yaqui and Mayo Rivers in the southern part of the Mexican state of Sonora outside the town of Cabora. Teresa Urrea, the 16-year-old daughter of ranch owner Tomás Urrea, was dead. Young Teresa had fallen ill two weeks before and no one knew what was wrong with her. The members of the household went about the sad task of preparing for the teenage girl’s wake. On the day of the wake, while laid out in the coffin, Teresa gasped for air and sat up suddenly. The people in attendance were amazed and stories of the girl’s resurrection spread quickly throughout southern Sonora and northern Sinaloa. Not known at the time, Teresa had spent the previous 14 days in a cataleptic state. Catalepsy is a nervous condition characterized by muscular rigidity and the body’s inability to react to external stimuli. In a cataleptic condition, the body’s involuntary functions such as breathing or heartbeat, also slow down dramatically. So, instead of being sick and then dying, Teresa’s body seized up and her muscles couldn’t move, thus giving the appearance of death. When she came to, Teresa said boldly that they should not get rid of the coffin because an indigenous girl who worked on the Urrea ranch named Huila would be dead soon. Huila died the next day. When asked how she could have known this, Teresa explained that while she was in the cataleptic state she was receiving visions from angels, saints and the Virgin Mary herself. This very thoroughly witnessed series of events was the beginning of something that would change not only the life of Teresa Urrea but the history of northern Mexico.

The year was 1889. The place was a rancho between the Yaqui and Mayo Rivers in the southern part of the Mexican state of Sonora outside the town of Cabora. Teresa Urrea, the 16-year-old daughter of ranch owner Tomás Urrea, was dead. Young Teresa had fallen ill two weeks before and no one knew what was wrong with her. The members of the household went about the sad task of preparing for the teenage girl’s wake. On the day of the wake, while laid out in the coffin, Teresa gasped for air and sat up suddenly. The people in attendance were amazed and stories of the girl’s resurrection spread quickly throughout southern Sonora and northern Sinaloa. Not known at the time, Teresa had spent the previous 14 days in a cataleptic state. Catalepsy is a nervous condition characterized by muscular rigidity and the body’s inability to react to external stimuli. In a cataleptic condition, the body’s involuntary functions such as breathing or heartbeat, also slow down dramatically. So, instead of being sick and then dying, Teresa’s body seized up and her muscles couldn’t move, thus giving the appearance of death. When she came to, Teresa said boldly that they should not get rid of the coffin because an indigenous girl who worked on the Urrea ranch named Huila would be dead soon. Huila died the next day. When asked how she could have known this, Teresa explained that while she was in the cataleptic state she was receiving visions from angels, saints and the Virgin Mary herself. This very thoroughly witnessed series of events was the beginning of something that would change not only the life of Teresa Urrea but the history of northern Mexico.

Teresa Urrea was born in the small town of Ocoroni, Sinaloa, Mexico, on October 15, 1873. Her mother was a 14-year old ranch hand named Cayetana Chávez from the small town of Tehueco, Sinaloa. Teresa’s mother was indigenous, but sources are conflicted as to which indigenous group she belonged. Some claim Mayo, other sources say Yaqui, and still others say that she was from the same tribe that bore the name of the town where she was born: Tehueco. Teresa’s father was Tomás Urrea, a wealthy rancher on whose lands Cayetana Chávez worked. Don Tomás did not recognize Teresa Urrea as his daughter until she was 16 years old in the year 1889. Before that, Teresa was raised mostly by her aunt and her mother alternating living between the towns of Cabora and nearby Aquihuiquichi. She lived among the Mayo and Yaqui people and could understand at least one indigenous language. As a young girl, when Teresa’s body would freeze into one of its cataleptic states, she was seen in two different ways by those around who knew her: Either she needed to be committed to a hospital never to be seen again, or she was a special person given a special gift. Always after coming out of these prolonged seizures, young Teresa would claim that she had visions or that she received instructions from divine beings. The biographers and researchers are unsure what happened to Teresa’s mother at around the age of thirty when Teresa was sixteen. Some say she died, some say she just left the Urrea rancho. In any event, because Teresa’s mother was no longer in the picture, Tomás recognized Teresa as his and sent for her to come live with him in the main ranch house. It was a different life from the drafty and dusty shack she lived in with her aunt and mother. It took her some time to get used to the life of privilege that the social position of rancher’s daughter afforded her. In the first few days of her life in the ranch house she made friends with the indigenous girl mentioned earlier, Huila. Huila was the daughter of a local healer, a curandera, and she had heard of Teresa’s reputation of trances and mystical experiences. Huila thought that Teresa’s gifts of vision and prophesy could be combined with healing, and so she taught Teresa about local native herbal and spiritual practices used to cure the sick. At the time of Huila’s death Teresa had already had somewhat of a reputation for herbal healing and prophesy with the locals and the ranch workers. Teresa’s remarkable “resurrection” only increased her legitimacy in the eyes of the true believers, and word of miracles associated with her spread across northern Mexico like wildfire.

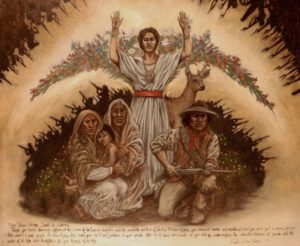

Within a few months of her famous 14-day cataleptic state, Teresa started drawing large crowds of people to the Urrea Ranch. She would lay her hands on people to diagnose unknown illnesses. Sometimes Teresa’s healings included a combination of the laying on of her hands with rubbing the affected area with a mixture of earth and her own saliva. In certain rare cases Teresa would mix her own blood with dirt along with herbs, as she had learned from her friend Huila. A subtle scent of roses was said to emanate from Teresa, and some attempted to collect her sweat or tears to use as perfume. As Teresa considered her powers to be divine gifts, she did not charge for her treatments. Teresa Urrea’s humility and her quiet but intense charisma eventually drew thousands to the Cabora ranch to be cured or simply just to witness a miracle.

Within a few months of her famous 14-day cataleptic state, Teresa started drawing large crowds of people to the Urrea Ranch. She would lay her hands on people to diagnose unknown illnesses. Sometimes Teresa’s healings included a combination of the laying on of her hands with rubbing the affected area with a mixture of earth and her own saliva. In certain rare cases Teresa would mix her own blood with dirt along with herbs, as she had learned from her friend Huila. A subtle scent of roses was said to emanate from Teresa, and some attempted to collect her sweat or tears to use as perfume. As Teresa considered her powers to be divine gifts, she did not charge for her treatments. Teresa Urrea’s humility and her quiet but intense charisma eventually drew thousands to the Cabora ranch to be cured or simply just to witness a miracle.

Teresa had an uncanny natural ability to address masses of people. She traveled to nearby towns and other ranches to talk before large groups in the open air. Sometimes she shared her predictions and sometimes she shared her thoughts on social issues. Before a crowd of hundreds, she predicted a massive flood and declared which areas would be spared. A flood came, as she had foretold, with the areas left untouched by water just as she had described in her public prediction. In her speeches Teresa often spoke out against abuses of the Catholic Church and emphasized the individual’s direct connection to the divine, casting away the need for clergy or any other intermediaries. As the church was aligned with the government at the time, some people saw Teresa’s comments as borderline sedition. By the end of 1889, just months after her miraculous rise from the dead, Teresa was being called “La Santa de Cabora,” or “The Saint of Cabora.” Another name for her was “Santa Niña,” or, “Holy girl.” Also, by the end of the year 1889 Teresa Urrea was getting the attention of higher-up Mexican government officials after the national press began covering her activities, specifically the Mexico City newspaper El Monitor Republicano.

As Teresa Urrea’s popularity as a folk saint grew throughout northern Mexico, entire towns began petitioning her for help. The village of Tomochic, Chihuahua called on Teresa after suffering from a long drought and experiencing socio-economic and political instability. On December 7, 1891, Teresa arrived at Tomochic, gave one of her inspiring speeches and then violence erupted between townsfolk and government officials. A second revolt on the day after Christmas caused 40 federal troops to be called to the area to quell the unrest. Teresa fled the town to escape possible arrest, but by then the national government, under the leadership of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz saw the folk saint as a rabble rouser and a threat to law and order. A well-organized group of Mayo people invoked the name of Santa Teresa Urrea during an attack on the town of Navojoa, Sonora on May 15, 1892. The insurgents took the plaza and killed several military officers to protest the discrimination and exploitation they suffered at the hands of the government and the landowners. As they claimed that Teresa Urrea was responsible for stirring up the discontent of the indigenous people of the region, The Díaz government called for Teresa Urrea’s arrest and exile.

As Teresa Urrea’s popularity as a folk saint grew throughout northern Mexico, entire towns began petitioning her for help. The village of Tomochic, Chihuahua called on Teresa after suffering from a long drought and experiencing socio-economic and political instability. On December 7, 1891, Teresa arrived at Tomochic, gave one of her inspiring speeches and then violence erupted between townsfolk and government officials. A second revolt on the day after Christmas caused 40 federal troops to be called to the area to quell the unrest. Teresa fled the town to escape possible arrest, but by then the national government, under the leadership of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz saw the folk saint as a rabble rouser and a threat to law and order. A well-organized group of Mayo people invoked the name of Santa Teresa Urrea during an attack on the town of Navojoa, Sonora on May 15, 1892. The insurgents took the plaza and killed several military officers to protest the discrimination and exploitation they suffered at the hands of the government and the landowners. As they claimed that Teresa Urrea was responsible for stirring up the discontent of the indigenous people of the region, The Díaz government called for Teresa Urrea’s arrest and exile.

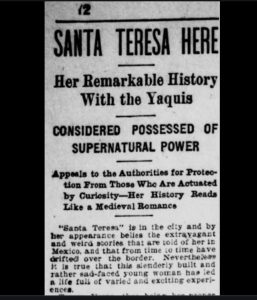

On May 19, 1892, Santa Teresa was apprehended and, without trial, was exiled to the United States, where she initially resided in Nogales, Arizona, in a house provided by her followers. There, as in all the places where she lived, Teresa continued to cure many people for free, especially Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Even in exile, she continued to influence her people. In November of 1895 Teresa relocated to Solomonville, Arizona. In this small mining town there lived two other high-profile Mexican exiles who were banished by the government of Porfirio Díaz, Lauro Aguirre and Flores Chapa. The two started a Spanish-language newspaper called El Independiente which actively called for the overthrow of the Díaz regime. Teresa Urrea helped with the newspaper and although her feet were now firmly planted in the United States, in 1896 she was again associated with another rebellion in Sonora. On August 12, Yaqui fighters stormed the Customs House in Nogales, on the Mexican side of the border to protest abuses by the government. During the attack, the indigenous attackers were heard shouting: “Long live the Saint of Cabora!” In addition, photos of her were found among the belongings of the Yaquis killed in the attack. Some fighters wore her photo over their hearts for added protection. The association of this event with Teresa significantly increased her image as a revolutionary. In the minds of some US and Mexican citizens the  idea prevailed that a woman who was worshiped by people like the Yaquis, and who apparently exercised mystical control over this uncontrollable group, must be a witch. Although Teresa used her powers for the “sacred” purpose of healing, it was considered that she applied them to charm the feared Yaquis into destroying the established social order and attacking the good citizens of both the US and Mexico. Consequently, some called Teresa Urrea the Nogales Witch. In 1896, Teresa moved again, and this time relocated to El Paso, Texas. It was here where Lauro Aguirre also moved his newspaper El Independiente. In the following years, the Mexican government tried to blame Teresa for many other minor uprisings and skirmishes fought by the indigenous and dispossessed mestizos against the ruling authorities. A New York Times article attributed over 1,000 deaths on the border and beyond to Teresa’s influence. Although Teresa made a public statement denouncing all violence in the El Paso Herald, in January of 1897 under direct orders from President Porfirio Díaz the Mexican government tried to kill her. She went into hiding.

idea prevailed that a woman who was worshiped by people like the Yaquis, and who apparently exercised mystical control over this uncontrollable group, must be a witch. Although Teresa used her powers for the “sacred” purpose of healing, it was considered that she applied them to charm the feared Yaquis into destroying the established social order and attacking the good citizens of both the US and Mexico. Consequently, some called Teresa Urrea the Nogales Witch. In 1896, Teresa moved again, and this time relocated to El Paso, Texas. It was here where Lauro Aguirre also moved his newspaper El Independiente. In the following years, the Mexican government tried to blame Teresa for many other minor uprisings and skirmishes fought by the indigenous and dispossessed mestizos against the ruling authorities. A New York Times article attributed over 1,000 deaths on the border and beyond to Teresa’s influence. Although Teresa made a public statement denouncing all violence in the El Paso Herald, in January of 1897 under direct orders from President Porfirio Díaz the Mexican government tried to kill her. She went into hiding.

In the year 1900, at the age of 27 Teresa Urrea married a man named Lupe Rodriguez who was a Yaqui miner. The press would later claim that Teresa’s marriage was a trick arranged by the Mexican government after word got out that her new husband tried to force her on a train that would take her back into Mexico. The marriage dissolved and the Santa de Cabora moved to California to help a sick boy who had meningitis. While in San Francisco Teresa contracted with a pharmaceutical company to go on a lengthy public tour as a healer. The tour never failed to draw large crowds, but the pace was demanding and there were logistical complications with traveling and setting up events that Teresa couldn’t tolerate. She eventually fell in love with her translator and bore him a daughter in 1902. They moved to Los Angeles where she continued her advocacy for social causes alongside her healing. In 1904 Teresa and her American husband had another child and bought a house after relocating to Ventura, California. The miraculous healer, sadly, died of tuberculosis at the age of 32. She was buried in Clifton, Arizona and her devotion continued long after her death. Scholars have yet to assess the full impact that this woman had on the cultural and political landscape of northern Mexico and the southwestern US during very troubled times.

REFERENCES

Domenq, Brianda. Veredas del Olvido: Teresa Urrea, la Santa de Cabora. Moorpark, CA: Floricanto Press, 2020. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3tAvnV8

Koshatka Seaman, Jennifer. Borderlands Curanderos: The Worlds of Santa Teresa Urrea and Don Pedrito Jaramillo. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2021. We are Amazon affiliates. Buy the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/391TAu8