Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In May of 1943, famous American clairvoyant and mystic Edgar Cayce went into a trance as he had done literally thousands of times before. The trance was induced to produce a reading for a slightly overweight, borderline-depressed, Pennsylvania housewife who was approaching middle age and wanted to get a better understanding of her place in the cosmic scheme of things. In this reading Cayce reviewed the woman’s past lives in which he saw her as a teacher, record keeper, interpreter of crystals and architect, among other things. One of the objectives of this reading was to give the Pennsylvania housewife some insight into her latent abilities from past lives that were not being used or developed in her current incarnation. Cayce mentioned that in one of her past lives she was a Maya priestess named Shekla. High Priestess Shekla lived in the Yucatán over a thousand years ago in a place called Ichakabal. Edgar Cayce’s readings were numbered and cataloged and reading number 3004-1 was that of the Pennsylvania housewife. It read:

In May of 1943, famous American clairvoyant and mystic Edgar Cayce went into a trance as he had done literally thousands of times before. The trance was induced to produce a reading for a slightly overweight, borderline-depressed, Pennsylvania housewife who was approaching middle age and wanted to get a better understanding of her place in the cosmic scheme of things. In this reading Cayce reviewed the woman’s past lives in which he saw her as a teacher, record keeper, interpreter of crystals and architect, among other things. One of the objectives of this reading was to give the Pennsylvania housewife some insight into her latent abilities from past lives that were not being used or developed in her current incarnation. Cayce mentioned that in one of her past lives she was a Maya priestess named Shekla. High Priestess Shekla lived in the Yucatán over a thousand years ago in a place called Ichakabal. Edgar Cayce’s readings were numbered and cataloged and reading number 3004-1 was that of the Pennsylvania housewife. It read:

“Before that the entity (meaning, the housewife) was in the Yucatan land, when there were those activities in which there were those groups that had caused dissension among the worshipers in the temple there of Ichakabal. In those activities we find whole groups of individuals being separated, and seeking for activities in other groups. The entity maintained that the activities there, in Ichakabal, were to be kept.”

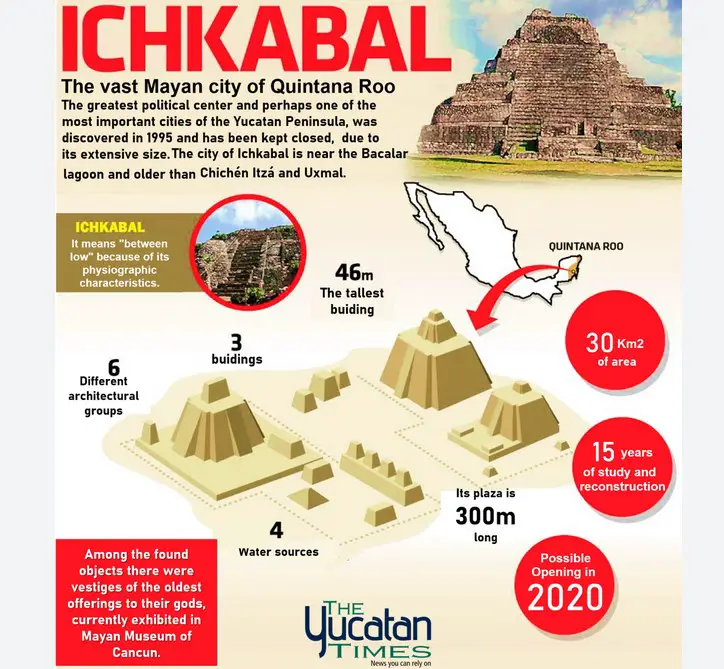

This may sound like a bunch of incoherent sentences open to interpretation, but Cayce researchers and Maya scholars alike are amazed that America’s so called “Sleeping Prophet” was naming an ancient Mexican lost city that had not yet been discovered and named. It was only in March of 1995 that a team of archaeologists named an important but previously unknown ruined city in the southern jungles of the Mexican state of Quintana Roo “Ichkabal.” The archaeologists had no idea of Cayce’s readings, and the name of the site means, “between two lows” owing to its construction on higher ground between two geographical depressions. Did Cayce just get lucky by coming up with the name of a future Maya ruin some 50 years before it was discovered? Are some people just reading into the reading? This is not the first time Mexico Unexplained has had an Edgar Cayce connection. Episode number 21 titled, “Is the Lost Library of Atlantis Located in the Yucatán?” looks into Cayce’s readings claiming that refugees from the sunken continent of Atlantis established a library in an ancient Maya city: https://mexicounexplained.com/lost-library-atlantis-located-yucatan/ Edgar Cayce was very familiar with this part of Mexico and claimed to have lived at least one past life among the ancient Maya. Cayce researchers have examined thoroughly the alleged prophet’s readings about the ancient Yucatán and some of the revelations Cayce had of the Maya civilization are uncanny. So, what do we know now about the vaguely referenced place, the recently discovered site of Ichkabal?

This may sound like a bunch of incoherent sentences open to interpretation, but Cayce researchers and Maya scholars alike are amazed that America’s so called “Sleeping Prophet” was naming an ancient Mexican lost city that had not yet been discovered and named. It was only in March of 1995 that a team of archaeologists named an important but previously unknown ruined city in the southern jungles of the Mexican state of Quintana Roo “Ichkabal.” The archaeologists had no idea of Cayce’s readings, and the name of the site means, “between two lows” owing to its construction on higher ground between two geographical depressions. Did Cayce just get lucky by coming up with the name of a future Maya ruin some 50 years before it was discovered? Are some people just reading into the reading? This is not the first time Mexico Unexplained has had an Edgar Cayce connection. Episode number 21 titled, “Is the Lost Library of Atlantis Located in the Yucatán?” looks into Cayce’s readings claiming that refugees from the sunken continent of Atlantis established a library in an ancient Maya city: https://mexicounexplained.com/lost-library-atlantis-located-yucatan/ Edgar Cayce was very familiar with this part of Mexico and claimed to have lived at least one past life among the ancient Maya. Cayce researchers have examined thoroughly the alleged prophet’s readings about the ancient Yucatán and some of the revelations Cayce had of the Maya civilization are uncanny. So, what do we know now about the vaguely referenced place, the recently discovered site of Ichkabal?

Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History, or INAH, was pleased to announce in October of 2023 that it had opened to the public the ruins of Ichkabal in the southern jungles of Quintana Roo state. The ruins were readied for tourists ahead of the construction of the eastern branch of the Tren Maya, or Maya Train, that will link 26 ancient Maya archaeological zones in the Yucatán Peninsula. Although the city itself dates back some 2,300 years, its discovery is quite recent.

In 1995, Alejandro Cano purchased land in the untouched tropical forest of the southern part of the state of Quintana Roo near the pueblo mágico, or “magical town” of Bacalar. Cano christened his future ranch “El Suspiro,” which means “The Sigh” in English. Some of Cano’s land bordered on an undeveloped part of the Ejido of Bacalar, which is communally owned by a number of families who live in the town of Bacalar. Cano was eager to explore the site of his future ranch when he noticed piles of stone covered in jungle several miles into the property. He had stumbled on a massive lost city deep in the tropical forests not even known to the people living in and around the town of Bacalar. Later archaeologists would determine that someone or a group of people made a vain attempt to loot the site sometime in the 1960s or 1970s but didn’t do much and probably gave up after working in the exhausting tropical heat and finding nothing. Besides the failed attempts of looters some 20 or 30 years before Alejandro Cano took possession of the site, the ruins that would later be called Ichkabal were untouched and unknown to anyone else. This was a huge city that had kept itself hidden beneath lush vegetation for hundreds of years. When Cano contacted INAH, they swore him to secrecy as they began sending researchers to the newly found city. Formal exploration commenced in 2003. After years of digging and surveying, the National Institute of Anthropology and History made a formal announcement of the discovery of Ichkabal only in April of 2009. They put renown Mexican archaeologist Enrique Hernández Nalda in charge of the project, and with a great push to increase research activity at the site, INAH set 2011 as the target year to open.

In 1995, Alejandro Cano purchased land in the untouched tropical forest of the southern part of the state of Quintana Roo near the pueblo mágico, or “magical town” of Bacalar. Cano christened his future ranch “El Suspiro,” which means “The Sigh” in English. Some of Cano’s land bordered on an undeveloped part of the Ejido of Bacalar, which is communally owned by a number of families who live in the town of Bacalar. Cano was eager to explore the site of his future ranch when he noticed piles of stone covered in jungle several miles into the property. He had stumbled on a massive lost city deep in the tropical forests not even known to the people living in and around the town of Bacalar. Later archaeologists would determine that someone or a group of people made a vain attempt to loot the site sometime in the 1960s or 1970s but didn’t do much and probably gave up after working in the exhausting tropical heat and finding nothing. Besides the failed attempts of looters some 20 or 30 years before Alejandro Cano took possession of the site, the ruins that would later be called Ichkabal were untouched and unknown to anyone else. This was a huge city that had kept itself hidden beneath lush vegetation for hundreds of years. When Cano contacted INAH, they swore him to secrecy as they began sending researchers to the newly found city. Formal exploration commenced in 2003. After years of digging and surveying, the National Institute of Anthropology and History made a formal announcement of the discovery of Ichkabal only in April of 2009. They put renown Mexican archaeologist Enrique Hernández Nalda in charge of the project, and with a great push to increase research activity at the site, INAH set 2011 as the target year to open.

As is often the case in Mexico, things did not go according to plan and the excavations at Ichkabal fell behind schedule. There were many factors that contributed to the 12 years of delays in opening this significant Maya “lost city” to the public. First, there was the lack of resources. A monumental city needs monumental financing, and the Mexican government’s budget was stretched thin and could not provide the necessary funds for a speedy but thorough excavation. The state of Quintana Roo was asked to contribute, but it, too, was strapped for cash. In addition, on April 14, 2010, the archaeologist in charge of Ichkabal, Enrique Hernández Nalda, died of lung cancer, leaving the project without a leader. This caused a complete shutdown of all activity at the site for many months. To add to all of this, some 25 square kilometers of the Ichkabal Archaeological Zone extended across Alejandro Cano’s property boundary and into the communal lands of the Ejido of Bacalar. The elders in charge of the ejido did not want to negotiate with the Mexican government to sell off part of their lands in order that they be included in a new local tourist attraction. Eventually, the ejido leaders did relent and were well compensated at the end of the negotiations. The 21st Century story of Ichkabal shows the importance of including local indigenous communities in cooperative development of cultural resources. Without the concessions made to the Ejido of Bacalar, this magnificent city would probably have never been open to the public.

What does the site of Ichkabal look like and what do researchers know about its history? The story of this large Maya city is still unfolding, and new information is added to its history on a weekly basis. Archaeologists believe that Ichkabal started as a small farming community sometime around 300 BC. As previously mentioned, the name Ichkabal means, “Between two Lows,” because it is on higher ground between two geographical depressions or lowland areas. The depressions even now are somewhat swampy, and evidence in the archaeological record shows how the ancient Maya shunted the water off to agricultural areas. With good soils and a control of water resources, the population grew, and the story of Ichkabal seemed to parallel the histories of other Maya city-states in the region. Ichkabal grew in importance, its rulers built monumental architecture, the elites warred with neighboring kingdoms, and by the 900s, the city was abandoned and left to the elements. Unlike other Maya cities, though, owing to its remoteness, there was not a squatter community living there after the Classic Maya collapse, and the renaissance of the Maya in the northern part of the Yucatán – as seen at places like Chichén Itzá – never made it as far south as Ichkabal. By the time Chichén Itzá was conquered by Mayapán in the 13th Century, Ichkabal had already long disappeared under a blanket of thick tropical vegetation.

What does the site of Ichkabal look like and what do researchers know about its history? The story of this large Maya city is still unfolding, and new information is added to its history on a weekly basis. Archaeologists believe that Ichkabal started as a small farming community sometime around 300 BC. As previously mentioned, the name Ichkabal means, “Between two Lows,” because it is on higher ground between two geographical depressions or lowland areas. The depressions even now are somewhat swampy, and evidence in the archaeological record shows how the ancient Maya shunted the water off to agricultural areas. With good soils and a control of water resources, the population grew, and the story of Ichkabal seemed to parallel the histories of other Maya city-states in the region. Ichkabal grew in importance, its rulers built monumental architecture, the elites warred with neighboring kingdoms, and by the 900s, the city was abandoned and left to the elements. Unlike other Maya cities, though, owing to its remoteness, there was not a squatter community living there after the Classic Maya collapse, and the renaissance of the Maya in the northern part of the Yucatán – as seen at places like Chichén Itzá – never made it as far south as Ichkabal. By the time Chichén Itzá was conquered by Mayapán in the 13th Century, Ichkabal had already long disappeared under a blanket of thick tropical vegetation.

Given the recency of its discovery and the fact that only a tiny fraction of the city has been excavated, archaeologists can only guess at how large Ichkabal was during its height, which was estimated to be around the year 700 AD. Researchers theorize that the city proper once covered 50 square kilometers, not including outlying agricultural settlements. In a rush to prepare for the site’s opening to tourists, much of the excavation work at Ichkabal has been limited to the central plaza which measures some 300 feet long by 150 feet wide and is located in the civic-ceremonial heart of the city. The plaza is flanked by several monumental buildings, including three pyramids and a structure nicknamed “Cinco Hermanos.” The three pyramids have the  unglamorous names of Building 4, Building 1 and Building 5. The largest of these is Building 4 which rises to a height of 120 feet high and has a base of 600 feet, thus making it larger than El Castillo, the pyramid also known as the Temple of Kukulcán at Chichén Itzá. Architecture here is done mostly in what researchers call the Petén style found in northern Guatemala and the southern Yucatán Peninsula. There are many smaller buildings at Ichkabal that still remain under the protection of the jungle, and have only been mapped. South of the main plaza there is a rectangular reservoir that still holds water called La Laguna de los Siete Colores, or “The Lake of the Seven Colors,” in English. The reservoir measures 240 feet long by 180 feet wide and its shores are reinforced by cut limestone blocks, almost making it look like a gigantic swimming pool. Throughout the site there are glyphs and various illustrations of historical and mythical scenes, but they have yet to be interpreted. Most of the concentrated effort at Ichkabal, as previously mentioned, has been to get the ruins tourist-ready and that means restoring the monumental buildings first. Eventually, the stones will speak and the history of Ichkabal will write itself through the reading of its surviving written record and by interpreting the other visual images at the site in the coming decades. And will Ichkabal eventually tell the story of the Maya priestess Shekla as revealed in the 1940s by America’s “Sleeping Prophet,” Edgar Cayce? Perhaps time will tell.

unglamorous names of Building 4, Building 1 and Building 5. The largest of these is Building 4 which rises to a height of 120 feet high and has a base of 600 feet, thus making it larger than El Castillo, the pyramid also known as the Temple of Kukulcán at Chichén Itzá. Architecture here is done mostly in what researchers call the Petén style found in northern Guatemala and the southern Yucatán Peninsula. There are many smaller buildings at Ichkabal that still remain under the protection of the jungle, and have only been mapped. South of the main plaza there is a rectangular reservoir that still holds water called La Laguna de los Siete Colores, or “The Lake of the Seven Colors,” in English. The reservoir measures 240 feet long by 180 feet wide and its shores are reinforced by cut limestone blocks, almost making it look like a gigantic swimming pool. Throughout the site there are glyphs and various illustrations of historical and mythical scenes, but they have yet to be interpreted. Most of the concentrated effort at Ichkabal, as previously mentioned, has been to get the ruins tourist-ready and that means restoring the monumental buildings first. Eventually, the stones will speak and the history of Ichkabal will write itself through the reading of its surviving written record and by interpreting the other visual images at the site in the coming decades. And will Ichkabal eventually tell the story of the Maya priestess Shekla as revealed in the 1940s by America’s “Sleeping Prophet,” Edgar Cayce? Perhaps time will tell.

REFERENCES

INAH Website

Cayce’s Associate for Research and Englightenment