Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Sometime in the late 1820s a portly French pastry chef known to history as Remontel opened a bakery in the town of Tacubaya which was then on the outskirts of Mexico City. The locals enjoyed Monsieur Remontel’s cream puffs and other sugary baked goods, but the pastry chef endured constant harassment from Mexican officers who were stationed in the town. The taunting and name-calling escalated to threats of physical violence against Remontel and in 1832 his beautiful Parisian-inspired pastry shop was completely ransacked. The angry French chef did not appeal to local authorities. He did not speak with those higher up in the Mexican military hierarchy. He didn’t even petition the French diplomatic corps stationed in Mexico City for help. Chef Remontel went directly to King Louis Philippe of France to ask for assistance. The French king proved sympathetic to the plight of his subject in that faraway land, so he appointed a small committee to investigate the chef’s claims. The king’s aides discovered many other abuses against French nationals in Mexico, including various lootings of French-owned businesses and even the execution of a French citizen accused of piracy. With claims of damages totaling into the millions of francs, the French monarch instructed his Prime Minister, Louis-Mathieu Molé, to demand that the Mexican government pay 600,000 pesos or 3 million French Francs as reparations. Of those 600,000 pesos, 60,000 of them would go to the Monsieur Remontel, the Tacubaya pastry chef who started this all. The chef’s shop was only worth about 1,000 pesos, and the Mexican government scoffed at such overblown monetary demands. Mexican president Anastasio Bustamante ignored all communications from France. The French responded with military force.

Sometime in the late 1820s a portly French pastry chef known to history as Remontel opened a bakery in the town of Tacubaya which was then on the outskirts of Mexico City. The locals enjoyed Monsieur Remontel’s cream puffs and other sugary baked goods, but the pastry chef endured constant harassment from Mexican officers who were stationed in the town. The taunting and name-calling escalated to threats of physical violence against Remontel and in 1832 his beautiful Parisian-inspired pastry shop was completely ransacked. The angry French chef did not appeal to local authorities. He did not speak with those higher up in the Mexican military hierarchy. He didn’t even petition the French diplomatic corps stationed in Mexico City for help. Chef Remontel went directly to King Louis Philippe of France to ask for assistance. The French king proved sympathetic to the plight of his subject in that faraway land, so he appointed a small committee to investigate the chef’s claims. The king’s aides discovered many other abuses against French nationals in Mexico, including various lootings of French-owned businesses and even the execution of a French citizen accused of piracy. With claims of damages totaling into the millions of francs, the French monarch instructed his Prime Minister, Louis-Mathieu Molé, to demand that the Mexican government pay 600,000 pesos or 3 million French Francs as reparations. Of those 600,000 pesos, 60,000 of them would go to the Monsieur Remontel, the Tacubaya pastry chef who started this all. The chef’s shop was only worth about 1,000 pesos, and the Mexican government scoffed at such overblown monetary demands. Mexican president Anastasio Bustamante ignored all communications from France. The French responded with military force.

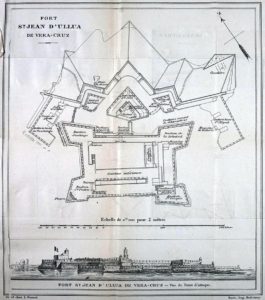

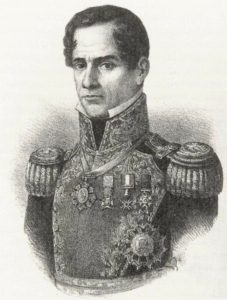

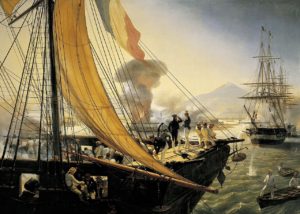

The first French intervention in Mexico is now known to history as the Pastry War. The conflict lasted from November of 1838 to March of 1839 and began with a massive naval blockade cutting off all of Mexico’s eastern ports. The French fleet under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Baudin stretched from the Yucatan to the Rio Grande. On November 27, 1838 the French began bombing the fort of San Juan de Ulúa located on a reef in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the city of Veracruz, Mexico’s chief port on its eastern seaboard. The fortress was considered invulnerable to naval attacks and earned the nickname, “The Gibraltar of the Indies.” However, the 186 obsolete and undermaintained guns and the 800 poorly-equipped and half-ill soldiers at San Juan de Ulúa were no match for the superior naval forces of the French. The fort fell the next day and the Mexican government formally declared war on France and ordered all French citizens out of Mexico. In an interesting twist of history, former army general and Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, was living on a ranch near the city of Veracruz at the time of the attack. The government in Mexico City called upon him and General Mariano Arista to lead 3,200 troops to fight the French at Veracruz. When he heard the news of the troops heading for the coast, the French fleet commander prepared to take the city of Veracruz with the intention of capturing General Santa Anna. In the early morning hours of December 5, 1838, the French landed 1,500 troops under the command of the 20-year-old Prince François de Joinville, the third son of the French King Louis-Phillipe. The prince’s forces attacked the Mexican military compound, catching Santa Anna and Arista off guard, but the Mexicans put up a fight. Although General Arista was captured by the French, Santa Anna managed to escape and fled to an old monastery that had been converted to an army barracks. Santa Anna regrouped

The first French intervention in Mexico is now known to history as the Pastry War. The conflict lasted from November of 1838 to March of 1839 and began with a massive naval blockade cutting off all of Mexico’s eastern ports. The French fleet under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Baudin stretched from the Yucatan to the Rio Grande. On November 27, 1838 the French began bombing the fort of San Juan de Ulúa located on a reef in the Gulf of Mexico overlooking the city of Veracruz, Mexico’s chief port on its eastern seaboard. The fortress was considered invulnerable to naval attacks and earned the nickname, “The Gibraltar of the Indies.” However, the 186 obsolete and undermaintained guns and the 800 poorly-equipped and half-ill soldiers at San Juan de Ulúa were no match for the superior naval forces of the French. The fort fell the next day and the Mexican government formally declared war on France and ordered all French citizens out of Mexico. In an interesting twist of history, former army general and Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, was living on a ranch near the city of Veracruz at the time of the attack. The government in Mexico City called upon him and General Mariano Arista to lead 3,200 troops to fight the French at Veracruz. When he heard the news of the troops heading for the coast, the French fleet commander prepared to take the city of Veracruz with the intention of capturing General Santa Anna. In the early morning hours of December 5, 1838, the French landed 1,500 troops under the command of the 20-year-old Prince François de Joinville, the third son of the French King Louis-Phillipe. The prince’s forces attacked the Mexican military compound, catching Santa Anna and Arista off guard, but the Mexicans put up a fight. Although General Arista was captured by the French, Santa Anna managed to escape and fled to an old monastery that had been converted to an army barracks. Santa Anna regrouped  and led a quick counterattack. The Mexicans were outgunned once again with much of the artillery fire coming from the French fleet in Veracruz harbor. Shot fired from an onboard cannon hit Santa Anna’s horse which collapsed on top of him, severely injuring his leg. With many casualties and many more injured, the Mexican military evacuated Veracruz. At the time of the blockade and the invasion, the French had the sea power but lacked the troops to occupy any big swaths of Mexican territory and had no immediate plans for a march on Mexico City. The closest French garrisons were located on the French West Indian islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, on the other end of the Caribbean almost 3,000 miles away. France had not planned for the hostilities to go beyond merely flexing its naval muscle; the French government thought that Mexico would cave in to their demands. The British offered their assistance to help mediate and to prevent escalations of hostilities on both sides. The British government dispatched their Northern American squadron to the Gulf of Mexico. Spearheading the France-Mexico negotiations was a future member of Queen Victoria’s Privy Council, British ambassador to the United States, Richard Pakenham. Before being named ambassador to the US, Pakenham served as a secretary to the British diplomatic legation in Mexico City and was well connected in Mexican political circles. The French blockade continued throughout the negotiations and the Mexican government eventually relented. A peace treaty was signed on March 9, 1839, giving better protection to French citizens in Mexico and forcing the nation of Mexico to pay the full amount of 600,000 pesos originally demanded before hostilities commenced. Monsieur Remontel enjoyed a refurbished bakery and continued to create his wonderful French pastries to the delight of his Mexican customers, unmolested.

and led a quick counterattack. The Mexicans were outgunned once again with much of the artillery fire coming from the French fleet in Veracruz harbor. Shot fired from an onboard cannon hit Santa Anna’s horse which collapsed on top of him, severely injuring his leg. With many casualties and many more injured, the Mexican military evacuated Veracruz. At the time of the blockade and the invasion, the French had the sea power but lacked the troops to occupy any big swaths of Mexican territory and had no immediate plans for a march on Mexico City. The closest French garrisons were located on the French West Indian islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, on the other end of the Caribbean almost 3,000 miles away. France had not planned for the hostilities to go beyond merely flexing its naval muscle; the French government thought that Mexico would cave in to their demands. The British offered their assistance to help mediate and to prevent escalations of hostilities on both sides. The British government dispatched their Northern American squadron to the Gulf of Mexico. Spearheading the France-Mexico negotiations was a future member of Queen Victoria’s Privy Council, British ambassador to the United States, Richard Pakenham. Before being named ambassador to the US, Pakenham served as a secretary to the British diplomatic legation in Mexico City and was well connected in Mexican political circles. The French blockade continued throughout the negotiations and the Mexican government eventually relented. A peace treaty was signed on March 9, 1839, giving better protection to French citizens in Mexico and forcing the nation of Mexico to pay the full amount of 600,000 pesos originally demanded before hostilities commenced. Monsieur Remontel enjoyed a refurbished bakery and continued to create his wonderful French pastries to the delight of his Mexican customers, unmolested.

This brief and unremarkable war had many important and long-lasting after-effects. For one, France showed the world that it was a naval power to be reckoned with. Lord Wellington, the British general who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo decades before the Pastry War, even mentioned in the House of Lords that the French capture of the Mexican fort of San Juan de Ulúa was the only example in history of a major fort totally subdued by a naval squadron. Indeed, like many wars, this small conflict showcased new military technologies including new types of guns and mortar bombs. France used steamships for the first time in war, as auxiliary or support vessels. The Mexican invasion also added to the prestige of the French royal family. France welcomed home the young Prince François as a national hero, having led the invading column into Veracruz and having captured General Arista with his own hand. The prince would enjoy a brief but distinguished naval career before marrying Princess Francisca, the sister of Dom Pedro Segundo, Emperor of Brazil.

This brief and unremarkable war had many important and long-lasting after-effects. For one, France showed the world that it was a naval power to be reckoned with. Lord Wellington, the British general who defeated Napoleon at Waterloo decades before the Pastry War, even mentioned in the House of Lords that the French capture of the Mexican fort of San Juan de Ulúa was the only example in history of a major fort totally subdued by a naval squadron. Indeed, like many wars, this small conflict showcased new military technologies including new types of guns and mortar bombs. France used steamships for the first time in war, as auxiliary or support vessels. The Mexican invasion also added to the prestige of the French royal family. France welcomed home the young Prince François as a national hero, having led the invading column into Veracruz and having captured General Arista with his own hand. The prince would enjoy a brief but distinguished naval career before marrying Princess Francisca, the sister of Dom Pedro Segundo, Emperor of Brazil.

The person who used the Pastry War to his advantage even more than the French prince was none other than General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna himself. Disgraced and blamed for the loss of Texas, Santa Anna enjoyed a quiet life of retirement secluded on his ranch near Veracruz at the time of the French intervention. He saw an opportunity and used the Pastry War to catapult himself back into the good graces of Mexico. Even though Santa Anna could not defend Veracruz and was defeated in his counterattack, many Mexicans saw him as a hero defending the nation. The fact that he suffered severe injuries and he almost died after doctors amputated his leg, only amplified his hero status. Santa Anna’s leg was even buried with great pomp and circumstance and given full military honors. The general would never let people forget the great sacrifice he made for his country. The already weak central government in Mexico City could not survive the aftermath of the war and on March 20, 1839, less than two weeks after Mexico signed the peace treaty with France, Santa Anna led a coup to take over the presidency. Many welcomed him back as same sort of savior to fix things although he faced immediate opposition from those who would raise rebel armies that he would eventually crush. Despite the surge of his popularity that made his return to the presidency somewhat easy, Santa Anna could not hold on to power for very long. Many politicians elected to the 1842 Mexican Congress opposed him, and Santa Anna’s proposal to restore a  depleted treasury by raising taxes did not go over well. Many states stopped dealing with the federal government and the Yucatán and the city of Nuevo Laredo even declared themselves independent republics at this time. The pressure against Santa Anna increased as the country effectively collapsed, and by December of 1844 he fled Mexico City. Federal forces loyal to a new president captured Santa Anna in the State of Veracruz and in 1845 he was exiled in Cuba, but not for long.

depleted treasury by raising taxes did not go over well. Many states stopped dealing with the federal government and the Yucatán and the city of Nuevo Laredo even declared themselves independent republics at this time. The pressure against Santa Anna increased as the country effectively collapsed, and by December of 1844 he fled Mexico City. Federal forces loyal to a new president captured Santa Anna in the State of Veracruz and in 1845 he was exiled in Cuba, but not for long.

Mexico repaid some of the debts as per the Pastry War peace treaty but not all of them, and the French used the unpaid debts as part of an excuse to justify another invasion of Mexico in 1861 known as The Second French Intervention. This action is more well known to Mexican students of history and even those with a mild interest in Mexican history. It produced such things as the second Mexican Empire of the French-backed Emperor Maximilian and the famous Battle of Puebla, which is celebrated to this day as Cinco de Mayo. When thinking of French involvement in Mexico, few have heard of the little-known 5-month war which happened decades before.

The Pastry War of Mexico remains a mere footnote in many Mexican history books, although it played a huge role in the shaping of the country. It’s amazing how a disgruntled portly pastry chef who literally had the ear of the emperor could have influenced history to such a great degree.

REFERENCES

Various online sources in English and Spanish.