Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

24-year-old Henri de Saussure left his home in Geneva, Switzerland to undertake a grand adventure. The year was 1854. Saussure was already an accomplished entomologist – one who studies insects – with a special fascination for the order Hymenoptera, which includes wasps, bees, and ants. The young Swiss scholar was also a trained minerologist. He left Europe on a multi-year expedition to collect insects and started in the Caribbean before heading to Mexico and then the United States. Saussure found himself in a remote part of the Mexican state of Puebla in 1855, in the semi-arid highlands. In his detailed journals he claimed to have discovered a very large “lost city” about 60 miles northeast of the city of Puebla which had formidable walled fortifications, well-planned streets, and monumental architecture typical of many other ancient Mesoamerican sites. As he noted various pits and trenches dug by looters, Saussure was not the first person to set foot in this vast archaeological zone. In fact, he called the place “Canton” after hearing people living nearby the site call it “Cantona,” “Caltonal,” or “Caltonac.” The latter two names, come from combining two words from the ancient Aztec language, Nahuatl, calli, or “house” and tonalli, meaning “sun.” So, essentially the name of the site means, “House of the Sun.” The variations of the present name, “Cantona,” were by no means what the early inhabitants of this place called their city. As there have been no written records discovered at the site, and no identifiable references to Cantona by other cultures in ancient Mexico, modern people have no idea what the ancients called this place. By the time the Aztecs had arrived in the area, the site had long since been abandoned and they must have assigned the name Caltonal or Caltonac to this place much as they had given names to other ruined cities, like Teotihuacán. The site now known as Cantona did not appear in any Spanish colonial documents because it was so remote and no one was living in the ruined city at the time of the European arrival, not even squatters. It is only briefly mentioned in an obscure 1790 geographical dictionary of New Spain with no details given. So, the credit of sharing Cantona with the wider world can be given to the Swiss bug expert who published the notes of his journeys when he returned to Europe. No one – besides occasional treasure hunters – took any serious interest in the site between Saussan’s visit and the early 1900s. It was then when Mexican researcher Nicolás León, using Henri Saussan’s notes, arrived at Cantona and described in detail its structures and other surface features. In 1903 he published a text called, The Archaeological Monuments in Cantona, but it generated little interest. It would be almost 60 years before anyone else paid any attention to this remote set of ruins. In the early 1960s Paris-born Mexican architect Paul Gendrop took hundreds of photos of the site and made exhaustive measurements of structures at Cantona. At around the same time, Mexican archaeologist Eduardo Noguera conducted research at the site, specifically concentrating on ceramics. More work occurred here in the 1980s, specifically prepping Cantona for tourists. Cantona underwent its first large-scale excavations in 1992 sponsored by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History under the direction of Ángel García Cook and Beatriz Leonor Merino Carrión. Cantona is open to the general public today but sees very few visitors. In fact, people who live in towns just a few miles away know very little about what is in their very own backyard.

24-year-old Henri de Saussure left his home in Geneva, Switzerland to undertake a grand adventure. The year was 1854. Saussure was already an accomplished entomologist – one who studies insects – with a special fascination for the order Hymenoptera, which includes wasps, bees, and ants. The young Swiss scholar was also a trained minerologist. He left Europe on a multi-year expedition to collect insects and started in the Caribbean before heading to Mexico and then the United States. Saussure found himself in a remote part of the Mexican state of Puebla in 1855, in the semi-arid highlands. In his detailed journals he claimed to have discovered a very large “lost city” about 60 miles northeast of the city of Puebla which had formidable walled fortifications, well-planned streets, and monumental architecture typical of many other ancient Mesoamerican sites. As he noted various pits and trenches dug by looters, Saussure was not the first person to set foot in this vast archaeological zone. In fact, he called the place “Canton” after hearing people living nearby the site call it “Cantona,” “Caltonal,” or “Caltonac.” The latter two names, come from combining two words from the ancient Aztec language, Nahuatl, calli, or “house” and tonalli, meaning “sun.” So, essentially the name of the site means, “House of the Sun.” The variations of the present name, “Cantona,” were by no means what the early inhabitants of this place called their city. As there have been no written records discovered at the site, and no identifiable references to Cantona by other cultures in ancient Mexico, modern people have no idea what the ancients called this place. By the time the Aztecs had arrived in the area, the site had long since been abandoned and they must have assigned the name Caltonal or Caltonac to this place much as they had given names to other ruined cities, like Teotihuacán. The site now known as Cantona did not appear in any Spanish colonial documents because it was so remote and no one was living in the ruined city at the time of the European arrival, not even squatters. It is only briefly mentioned in an obscure 1790 geographical dictionary of New Spain with no details given. So, the credit of sharing Cantona with the wider world can be given to the Swiss bug expert who published the notes of his journeys when he returned to Europe. No one – besides occasional treasure hunters – took any serious interest in the site between Saussan’s visit and the early 1900s. It was then when Mexican researcher Nicolás León, using Henri Saussan’s notes, arrived at Cantona and described in detail its structures and other surface features. In 1903 he published a text called, The Archaeological Monuments in Cantona, but it generated little interest. It would be almost 60 years before anyone else paid any attention to this remote set of ruins. In the early 1960s Paris-born Mexican architect Paul Gendrop took hundreds of photos of the site and made exhaustive measurements of structures at Cantona. At around the same time, Mexican archaeologist Eduardo Noguera conducted research at the site, specifically concentrating on ceramics. More work occurred here in the 1980s, specifically prepping Cantona for tourists. Cantona underwent its first large-scale excavations in 1992 sponsored by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History under the direction of Ángel García Cook and Beatriz Leonor Merino Carrión. Cantona is open to the general public today but sees very few visitors. In fact, people who live in towns just a few miles away know very little about what is in their very own backyard.

Archaeologists and other researchers divide the history of Cantona into four phases spanning about 2,000 years:

The Pre-Cantona Phase took place between about 1000 BC and 600 BC. During this time there were a few small villages at the 12-square-kilometer site but no stone buildings of any kind. Ceramic artifacts associated with this phase indicate that Cantona’s original inhabitants came from the Tehuacán Valley to the south and the valleys of Tlaxcala to the site’s immediate west. In the latter part of this phase, around 750 AD, the settlements at Cantona became more dense and urban, with adjoining housing being built. Also, the inhabitants of Cantona began building roads to connect the settlements at the site with each other and with villages farther away. It was near the end of this phase, in the 7th Century BC that the people of Cantona began exploiting the obsidian resources of the nearby Zaragoza-Oyameles Mountains. This drew much attention to the growing population center, and with the flow of obsidian through Catona came more wealth and more social and political stratification.

Researchers give the name “Cantona I” to the phase at the site dating from 600 BC to 50 AD. During this time the city exploded in population and the people of Cantona built much of the massive buildings still visible today. During Phase I Cantona became one of the largest cities in ancient Mexico, even rivalling the central Mexican powerhouse Teotihuacán to the west. Archaeologists believe that during this time the city drew people from the Gulf Coast of Veracruz and the Mexican highlands. Cantona’s trade networks extended for hundreds of miles. Because of threats of invasion from various foreign powers interested in taking over this vast trade network, the rulers of Cantona constructed elaborate and extensive fortifications, and a rigid system of city streets and roads extending away from the city. The city saw a building frenzy during Phase I to include plazas, pyramids and ball courts. Some archaeologists believe that during this time the city had a population of 80,000, and with such a dynamic and diverse population there was intense craft specialization as evidenced by the many workshops uncovered. There was also great social stratification, with a very wealthy ruling elite at the top. Some researchers believe that Cantona was such a great regional power in the years straddling BC and AD that it helped cause the downfall of Teotihuacán by denying it valuable obsidian and by cutting off its access to Gulf Coast trading areas and even trade with the lucrative Maya civilization. For more information about Teotihuacán, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 45 https://mexicounexplained.com/teotihuacan-lost-city-gods/

Researchers give the name “Cantona I” to the phase at the site dating from 600 BC to 50 AD. During this time the city exploded in population and the people of Cantona built much of the massive buildings still visible today. During Phase I Cantona became one of the largest cities in ancient Mexico, even rivalling the central Mexican powerhouse Teotihuacán to the west. Archaeologists believe that during this time the city drew people from the Gulf Coast of Veracruz and the Mexican highlands. Cantona’s trade networks extended for hundreds of miles. Because of threats of invasion from various foreign powers interested in taking over this vast trade network, the rulers of Cantona constructed elaborate and extensive fortifications, and a rigid system of city streets and roads extending away from the city. The city saw a building frenzy during Phase I to include plazas, pyramids and ball courts. Some archaeologists believe that during this time the city had a population of 80,000, and with such a dynamic and diverse population there was intense craft specialization as evidenced by the many workshops uncovered. There was also great social stratification, with a very wealthy ruling elite at the top. Some researchers believe that Cantona was such a great regional power in the years straddling BC and AD that it helped cause the downfall of Teotihuacán by denying it valuable obsidian and by cutting off its access to Gulf Coast trading areas and even trade with the lucrative Maya civilization. For more information about Teotihuacán, please see Mexico Unexplained Episode 45 https://mexicounexplained.com/teotihuacan-lost-city-gods/

The Cantona I Phase shifted to the Cantona II Phase around 50 AD. This phase lasted until around 600 AD. This was the time during which Cantona reached its peak. In the early centuries AD, the building at Cantona intensified. During this phase the rulers of Cantona constructed some 20 ball courts and temples were expanded. Luxury goods found at the site indicate that during this time Cantona had contact with both the Pacific and Gulf coasts, the Maya Lowlands all the way into modern-day Guatemala, and at least secondary contact with turquoise mines located in the modern American state of New Mexico. Cantona’s major export, as it had been for hundreds of years, was obsidian, but in Phase II it also exported many hand-crafted products and agricultural products as well. Closer to the end of the Cantona II Phase, the building of fortifications became more intense, as if the people of this massive city were trying desperately to defend themselves against a very persistent or powerful enemy.

The Cantona III Phase beginning around 600 AD and lasting until about 950 AD sees an even more desperate attempt by the city to defend itself. It was during this period that a military elite took control of the city and human sacrifices increased. This change in governmental authority was a reaction to many external pressures and some of the internal pressures coming from its high population and dense urbanization. During this more militaristic phase, art ceased to be made at Cantona along with the creation of religious figurines and effigies. The city, it seems, was in some serious trouble.

The last phase of the Cantona chronology was brief and lasted from about 950 to about 1050 AD. Called “Cantona IV”, this phase dealt mostly with the site’s abandonment. A series of droughts and invasions from northern Chichimec tribes caused people to lose faith in the government. During this century or so of Phase IV the city’s population plummeted to only a few thousand people. The Chichimeca invaders who seemed to torment the remaining people at Cantona with their successive raids had no desire to take over the city or to populate it with their own people. By 1050 AD Cantona was completely abandoned.

The last phase of the Cantona chronology was brief and lasted from about 950 to about 1050 AD. Called “Cantona IV”, this phase dealt mostly with the site’s abandonment. A series of droughts and invasions from northern Chichimec tribes caused people to lose faith in the government. During this century or so of Phase IV the city’s population plummeted to only a few thousand people. The Chichimeca invaders who seemed to torment the remaining people at Cantona with their successive raids had no desire to take over the city or to populate it with their own people. By 1050 AD Cantona was completely abandoned.

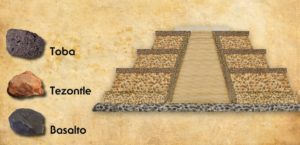

So, what does the current archaeological site of Cantona look like? It’s important to note that only 1-10% of the site has been excavated, but much of the monumental architecture and the city’s many buildings, walls, platforms, and pyramids have been cleared of the high desert scrub plants that took over after its abandonment. Only a small portion of the site’s 12 square kilometers is open to tourists. Nothing at Cantona was built with mortar or plaster. Series of carved stones were stacked one on top another to form even the largest buildings. The Acropolis is located on Cantona’s highest point where the elites lived and where the bulk of the important civic-ceremonial buildings are found. The city has an intricate network of some 500 narrow walkways that controlled foot traffic within Cantona. The largest road called “First Avenue” by archaeologists, stretches some 1,840 feet long. Besides the low pyramids and public plazas, some 3,000 individual patios have been identified which helps researchers to estimate population. The most stunning feature of the site  must be the high and thick walls used to defend the city. Also, to date, archaeologists have uncovered 27 ball courts at Cantona, most of them located near the center of the city. Of special note is a miniature ball court, about a third of the size of the average size of a court at Cantona. Some researchers believe that it served some ritual purpose, while others believe it was a special training center for small children. A more fringe theory entertains the idea that the tiny ball court was reserved for dwarfs, but there were most likely not enough dwarfs in the region to field two ball court teams. For more information about the Mesoamerican ball game, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 53: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-mesoamerican-ballgame/

must be the high and thick walls used to defend the city. Also, to date, archaeologists have uncovered 27 ball courts at Cantona, most of them located near the center of the city. Of special note is a miniature ball court, about a third of the size of the average size of a court at Cantona. Some researchers believe that it served some ritual purpose, while others believe it was a special training center for small children. A more fringe theory entertains the idea that the tiny ball court was reserved for dwarfs, but there were most likely not enough dwarfs in the region to field two ball court teams. For more information about the Mesoamerican ball game, please see Mexico Unexplained episode number 53: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-mesoamerican-ballgame/

Attached to the Cantona archaeological zone is the nearby Tzinacamóztoc Cave, which has drawn a lot of attention from researchers. The four-and-a-half-mile lava tube in the side of a volcanic hill called the Los Humeros caldera contains an interesting artificial rock structure on the cave floor underneath a natural skylight. The structure includes a pentagon-shaped enclosure around a central mound which is topped by a basalt slab resembling an altar. Detailed measurements and computer modeling indicate that this was used as an astronomical observatory and was tied to the Mesoamerican calendar. No artifacts have yet been found in this cave and no one knows if this unique observatory pre-dates the settlement of Cantona or what role it played in the religious or civic life of the city. Exactly who built this deep inside the lava tube remains a mystery.

The ancient city of Cantona dominated the eastern area of Mexico for many centuries, had a massive population and played a significant role in the history of ancient Mexico. Very few people have even heard of this important place and much research is yet to be done here to unravel Cantona’s many mysteries.

REFERENCES

García Cook, Angel, and Merino Carrión, Beatriz Leonor 1998 “Cantona: urbe prehispánica en el altiplano central de México.” Latin American Antiquity 9(3):191–216.

INAH Website (in Spanish)