Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

In 1587 the Franciscan friar Alonso Ponce de Leon arrived in the part of New Spain now known as the Mexican state of Sinaloa. This was part of his grand 5-year tour to inspect the 166 Franciscan missions of New Spain as well as several run by the Dominicans, Augustinians, and the Jesuits. Father Alonso traveled from what is now the country of Nicaragua all the way up to what is now the Mexican state of Sonora. He traveled so extensively that he is often referred to as one of Mexico’s first tourists. As part of his role as inspector he was tasked with documenting everything, from conditions at the missions, to local flora and fauna, to the customs of the various and many indigenous groups he encountered along the way, including very vivid and thorough details about everything from native food preparation to music to farming techniques. Father Alonso had with him a personal secretary, a friar named Antonio de Ciudad Real who once served as the musical director or chorister for the infamous Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa who was responsible for the great Maya book burning of 1562 discussed in Mexico Unexplained Episode 106: https://mexicounexplained.com/great-maya-book-burning/ Ciudad Real compiled accounts of their journeys in a very large book called Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva Espana or, in English, Curious and Learned Treatise on the Wonders of New Spain. The work was rediscovered in the 1870s and parts of it have been republished and studied by scholars. There is currently no English translation of any of this lengthy work. In this book, the traveling clerics describe a gigantic monument made of seashells standing almost 90 feet tall cared for by local indigenous people referred to as the Totorames. The inland neighbors of these people called them the “Temuretes” which translates from their now-extinct language as “toads” because the Totorames lived near and on the water. Early Spanish accounts show the Totorames living in small chiefdoms or kingdoms along the Pacific coast. The kingdoms – numbering about 6 or 7 – interacted peacefully with one another, shared a common language and culture, and may have shared ceremonial sites. The villages in the Totorame kingdoms were each dedicated to a

In 1587 the Franciscan friar Alonso Ponce de Leon arrived in the part of New Spain now known as the Mexican state of Sinaloa. This was part of his grand 5-year tour to inspect the 166 Franciscan missions of New Spain as well as several run by the Dominicans, Augustinians, and the Jesuits. Father Alonso traveled from what is now the country of Nicaragua all the way up to what is now the Mexican state of Sonora. He traveled so extensively that he is often referred to as one of Mexico’s first tourists. As part of his role as inspector he was tasked with documenting everything, from conditions at the missions, to local flora and fauna, to the customs of the various and many indigenous groups he encountered along the way, including very vivid and thorough details about everything from native food preparation to music to farming techniques. Father Alonso had with him a personal secretary, a friar named Antonio de Ciudad Real who once served as the musical director or chorister for the infamous Archbishop of the Yucatán, Diego de Landa who was responsible for the great Maya book burning of 1562 discussed in Mexico Unexplained Episode 106: https://mexicounexplained.com/great-maya-book-burning/ Ciudad Real compiled accounts of their journeys in a very large book called Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva Espana or, in English, Curious and Learned Treatise on the Wonders of New Spain. The work was rediscovered in the 1870s and parts of it have been republished and studied by scholars. There is currently no English translation of any of this lengthy work. In this book, the traveling clerics describe a gigantic monument made of seashells standing almost 90 feet tall cared for by local indigenous people referred to as the Totorames. The inland neighbors of these people called them the “Temuretes” which translates from their now-extinct language as “toads” because the Totorames lived near and on the water. Early Spanish accounts show the Totorames living in small chiefdoms or kingdoms along the Pacific coast. The kingdoms – numbering about 6 or 7 – interacted peacefully with one another, shared a common language and culture, and may have shared ceremonial sites. The villages in the Totorame kingdoms were each dedicated to a  principal activity, either fishing, agriculture, or the gathering of salt. A Totorame fishing technique of constructing fencelike barriers out of young mangrove branches and placing them in the lagoons and estuaries to catch fish is still in use by locals today. As to the published account of the friars Ponce and Ciudad Real, in their thousands of pages of written material, the unique shell pyramid of the Totorames seemed to be lost among all the other details of the many places they visited. If anyone wanted to deliberately search for El Calón, they would have been hard pressed to do so just from these 16th Century descriptions. There were Totorame villages nearby, and it was near the coastal area of lagoons and estuaries close to what is now the border of Nayarit and Sinaloa. Although Ponce and Ciudad Real never mention the indigenous name of the pyramid complex, the river by the site was called Auchén, but that name is lost to history and its very meaning is unknown. After the Spanish thoroughly conquered the area, the gigantic pyramid made of shells slowly succumbed to Mother Nature. The Totorame people died off or blended in with the ever-growing mestizo population around them, and knowledge of this sacred place was lost. By the time the Piramide de Conchas or Shell Pyramid was rediscovered in 1968, it looked like so many older lost monuments. It appeared to be just a strange hill covered with vegetation and dirt. As El Calón is in a somewhat inaccessible area, even the modern-day locals were unaware of its existence, and of course, had no idea why it was there or who built it.

principal activity, either fishing, agriculture, or the gathering of salt. A Totorame fishing technique of constructing fencelike barriers out of young mangrove branches and placing them in the lagoons and estuaries to catch fish is still in use by locals today. As to the published account of the friars Ponce and Ciudad Real, in their thousands of pages of written material, the unique shell pyramid of the Totorames seemed to be lost among all the other details of the many places they visited. If anyone wanted to deliberately search for El Calón, they would have been hard pressed to do so just from these 16th Century descriptions. There were Totorame villages nearby, and it was near the coastal area of lagoons and estuaries close to what is now the border of Nayarit and Sinaloa. Although Ponce and Ciudad Real never mention the indigenous name of the pyramid complex, the river by the site was called Auchén, but that name is lost to history and its very meaning is unknown. After the Spanish thoroughly conquered the area, the gigantic pyramid made of shells slowly succumbed to Mother Nature. The Totorame people died off or blended in with the ever-growing mestizo population around them, and knowledge of this sacred place was lost. By the time the Piramide de Conchas or Shell Pyramid was rediscovered in 1968, it looked like so many older lost monuments. It appeared to be just a strange hill covered with vegetation and dirt. As El Calón is in a somewhat inaccessible area, even the modern-day locals were unaware of its existence, and of course, had no idea why it was there or who built it.

In 1968, Stuart D. Scott of the State University of New York at Buffalo was surveying 25 linear miles of waterway comprising most of the Estuary of Teacapán in southern Sinaloa. He noticed the strange hill and decided to investigate. Clearing away some of the brush and dirt, Scott realized that this was not a hill but was a manmade structure comprised almost entirely of seashells. The professor had seen many ancient maritime middens or trash heaps of discarded seashells, but this was too symmetrical, and way too large. Also, many of the shells, mostly local mollusks, had not even been opened, which indicated this was not just a refuse heap. Another field season with more graduate students in tow would lead to more finds and revelations. Cursory digs into the pyramid would uncover various artifacts including pottery jars, pieces of obsidian, and a few luxury goods. Most of these artifacts were found in an interior chamber with clay floors. During the same field season, the researchers would also find other similar sites nearby, but smaller, and there seemed to be too much for them to study.

In 1968, Stuart D. Scott of the State University of New York at Buffalo was surveying 25 linear miles of waterway comprising most of the Estuary of Teacapán in southern Sinaloa. He noticed the strange hill and decided to investigate. Clearing away some of the brush and dirt, Scott realized that this was not a hill but was a manmade structure comprised almost entirely of seashells. The professor had seen many ancient maritime middens or trash heaps of discarded seashells, but this was too symmetrical, and way too large. Also, many of the shells, mostly local mollusks, had not even been opened, which indicated this was not just a refuse heap. Another field season with more graduate students in tow would lead to more finds and revelations. Cursory digs into the pyramid would uncover various artifacts including pottery jars, pieces of obsidian, and a few luxury goods. Most of these artifacts were found in an interior chamber with clay floors. During the same field season, the researchers would also find other similar sites nearby, but smaller, and there seemed to be too much for them to study.

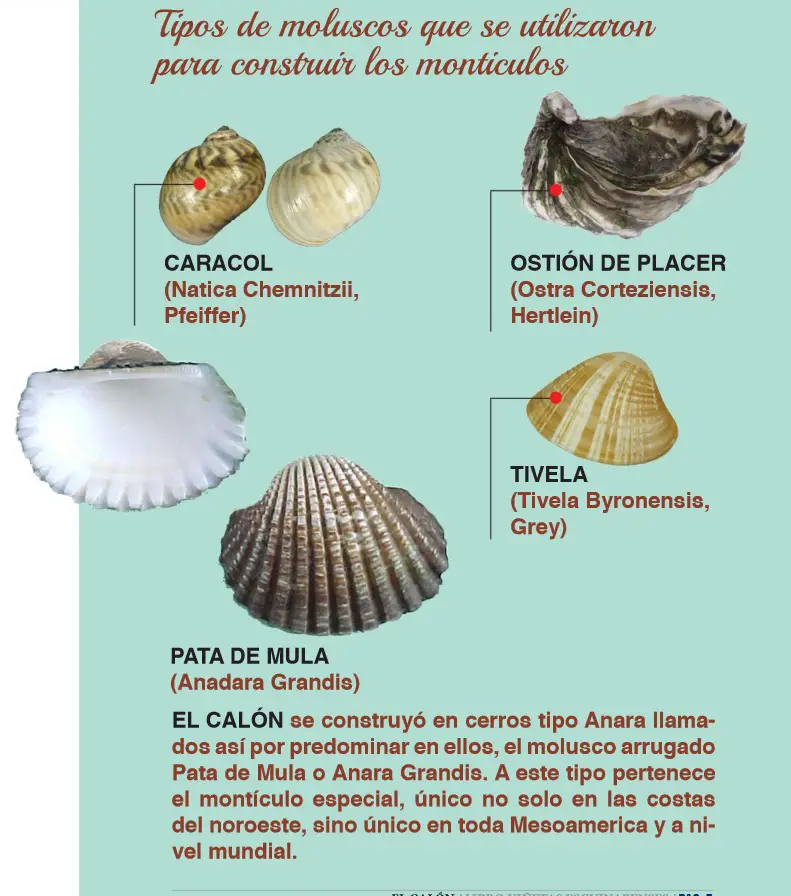

The site of the large seashell pyramid has since been christened El Calón and is now open to tourists, although it is still difficult to get to, accessible only by boat and a short hike through mangrove swamps and forest. In the year 2017 Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History – or INAH – out of Mexico City beefed up its presence in the state of Sinaloa and took a keener interest in the Piramide de Conchas and the surrounding sites. Luis Alfonso Grave Tirado is the principal scholar investigating the ancient maritime cultures of the region who is on INAH’s payroll. Grave Tirado and his team estimate that the main pyramid at El Calón was built using over 275 million seashells. The shells are mostly clam and oyster, including an overabundance of a local variety called pata de mula. Archaeologists estimate that it took 100 years to finish the large pyramid at El Calón. Several samples of shells and other organic materials extracted from the pyramid gave some interesting dates in the 1970s when researchers were trying to date the site. Original estimates of dates went back to before 2000 BC, but the 21st-Century official story coming from the National Institute of Anthropology and History dates the site’s earliest construction to around 500 AD, with its heyday around 800 AD. The construction corresponds to what archaeologists call “The Aztatlán Horizon Period” of western coastal Mexico. No one knows if the ancestors of the Totorame people who were described by the Spanish as being caretakers of the pyramid were the ones who actually built it. Those theorists who claim that the pyramid is really 4,000 years old believe that an unknown seafaring people from Central America may have been responsible for El Calón’s construction. Researchers are still trying to piece together a timeline for the shell pyramid and the other sites nearby.

The seashell pyramid is some 75 feet tall and measures 300 feet by 240 feet at its base. The top of the pyramid has a flat surface measuring 45 feet by 45 feet. It is unknown what sort of structure, if any, existed on the top of the pyramid. If the other pyramids in ancient Mexico are any indication, El Calón’s Piramide de Conchas probably had a temple on top or some other ceremonial building associated with rituals to ensure a good harvest from the sea. The top of the pyramid offers sweeping views of the Sierra Madres, the local estuaries and lagoons, as well as the Pacific Ocean. The pyramid itself is made up of successive layers of shells and packed earth each measuring about 1 foot thick. In some cases throughout the immediate area a mixture of crushed shells and clay was also used in the building process. The closest stones to be used for building are located some 3 weeks away on foot, so there was no stone used in the construction of the pyramid or in any of the much smaller structures at El Calón. This seashell pyramid, like its other ancient cousins in Mexico, is aligned 15.5 degrees east of north. Besides the alignment and the fact that it was used for religious rituals, the shell pyramid of El Calón is unique in Mexico. In the state of Tabasco, on the Gulf Coast, there are some smaller platform structures constructed in the same way, but nothing quite this big and no pyramids. As an interesting aside, shell platforms similar in construction to those found in Tabasco and at El Calón have also been found in the American state of Florida. Archaeologists hesitate in making any connections.

The seashell pyramid is some 75 feet tall and measures 300 feet by 240 feet at its base. The top of the pyramid has a flat surface measuring 45 feet by 45 feet. It is unknown what sort of structure, if any, existed on the top of the pyramid. If the other pyramids in ancient Mexico are any indication, El Calón’s Piramide de Conchas probably had a temple on top or some other ceremonial building associated with rituals to ensure a good harvest from the sea. The top of the pyramid offers sweeping views of the Sierra Madres, the local estuaries and lagoons, as well as the Pacific Ocean. The pyramid itself is made up of successive layers of shells and packed earth each measuring about 1 foot thick. In some cases throughout the immediate area a mixture of crushed shells and clay was also used in the building process. The closest stones to be used for building are located some 3 weeks away on foot, so there was no stone used in the construction of the pyramid or in any of the much smaller structures at El Calón. This seashell pyramid, like its other ancient cousins in Mexico, is aligned 15.5 degrees east of north. Besides the alignment and the fact that it was used for religious rituals, the shell pyramid of El Calón is unique in Mexico. In the state of Tabasco, on the Gulf Coast, there are some smaller platform structures constructed in the same way, but nothing quite this big and no pyramids. As an interesting aside, shell platforms similar in construction to those found in Tabasco and at El Calón have also been found in the American state of Florida. Archaeologists hesitate in making any connections.

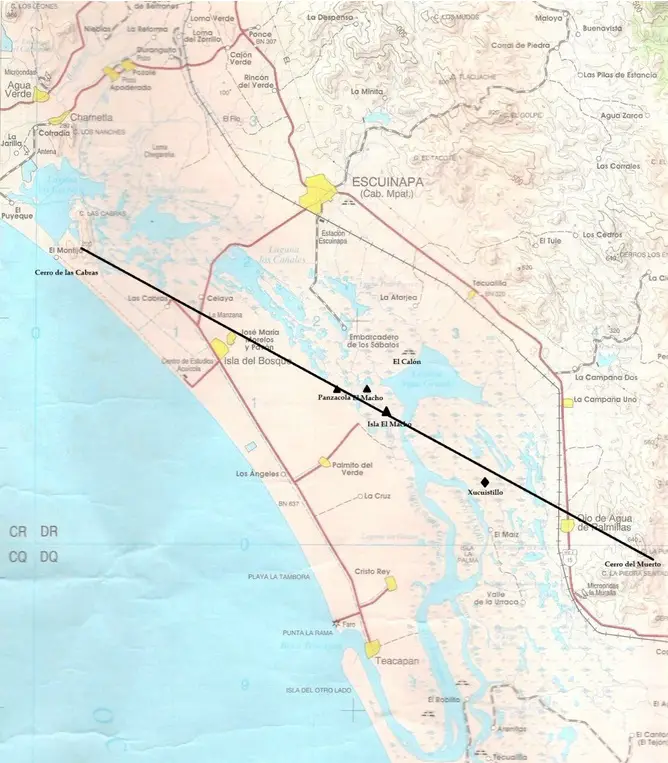

In the early decades of the 21st Century much work has been done at neighboring sites in southern Sinaloa built in the same fashion as El Calón and dating to the same time period. Four notable sites are Xicuistillo, El Macho, Isla El Macho and Panzacola (not to be confused with Pensacola, Florida). Of specific interest to current INAH scholars is the site of Isla El Macho. It contains 4 structures entirely made of shells in its civic-ceremonial center. One is a curious U-shaped building that puzzles archaeologists. Another interesting structure is a Mesoamerican ball court, perhaps the only ball court ever made from seashells in the history of Mexico. Luis Alfonso Grave Tirado is quick to point out that these shell sites fall on an axis between two mountains that were considered sacred by the indigenous people living in the area at the time of the Conquest. The mountains are called Cerro de las Cabras and Cerro de Muerto. Again, the original native names of these mountains are lost and the meaning of the alignment is also unknown.

Excavations are ongoing at all the Sinaloa shell sites and interesting finds are constantly being made, thus adding to our understanding of the area in prehistory. Although the makers of El Calón left behind no written records or elaborately decorated public monuments, that which they did leave behind still has a lot to tell modern people. For example, in March of 1998, an elaborate stone head was unearthed near the base of the great shell pyramid. Was this a ruler, a god, or was it an imported luxury good? Elaborate feather works have been discovered at El Calón as well with origins around modern-day Tlaxcala in central Mexico. Obsidian objects traced to the Zacatecas area were also found inside the shell pyramid. Researchers theorize that the ancient people of the area traded dry fish – especially shrimp – and salt with the rest of ancient Mexico, so there was definitely trade and possibly cultural exchange between this remote coastal area and the rest of Mesoamerica. The full story of this mysterious place is still being slowly pieced together.

Excavations are ongoing at all the Sinaloa shell sites and interesting finds are constantly being made, thus adding to our understanding of the area in prehistory. Although the makers of El Calón left behind no written records or elaborately decorated public monuments, that which they did leave behind still has a lot to tell modern people. For example, in March of 1998, an elaborate stone head was unearthed near the base of the great shell pyramid. Was this a ruler, a god, or was it an imported luxury good? Elaborate feather works have been discovered at El Calón as well with origins around modern-day Tlaxcala in central Mexico. Obsidian objects traced to the Zacatecas area were also found inside the shell pyramid. Researchers theorize that the ancient people of the area traded dry fish – especially shrimp – and salt with the rest of ancient Mexico, so there was definitely trade and possibly cultural exchange between this remote coastal area and the rest of Mesoamerica. The full story of this mysterious place is still being slowly pieced together.

REFERENCES

Grave Tirado, Luis Alfonso. El Calón, un espacio sagrado en las marismas del sur de Sinaloa. Mexico City: UNAM, 2010 (in Spanish)