Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

“I love the song of the mockingbird,

bird of four hundred voices;

I love the color of jade

and the unnerving perfume of flowers,

but I love my brother more;

mankind.”

So read the words – translated into English – written on Mexico’s former 100-peso note, one of the few examples of poetry on a banknote of a major world currency. The words are ancient and they date back to the mid-1400s. The poem on the reddish bill is accompanied by the likeness of its author, Nezahualcoyotl, one of the most intelligent and accomplished rulers in pre-Conquest Mexico. This important king ruled the wealthy and vital Kingdom of Texcoco, located on the eastern shores of the lake of the same name, which eventually became part of the Aztec Empire. Nezahualcoyotal lived a long life, from 1402 to 1472. During that time, he bore witness to and participated in some of the most important events in the history of ancient Mexico.

So read the words – translated into English – written on Mexico’s former 100-peso note, one of the few examples of poetry on a banknote of a major world currency. The words are ancient and they date back to the mid-1400s. The poem on the reddish bill is accompanied by the likeness of its author, Nezahualcoyotl, one of the most intelligent and accomplished rulers in pre-Conquest Mexico. This important king ruled the wealthy and vital Kingdom of Texcoco, located on the eastern shores of the lake of the same name, which eventually became part of the Aztec Empire. Nezahualcoyotal lived a long life, from 1402 to 1472. During that time, he bore witness to and participated in some of the most important events in the history of ancient Mexico.

On April 28, 1402, at the royal palace of Texcoco an heir to the throne was born. At birth he was called Ahcolmiztli, which comes from combining two Nahuatl words, miztli, meaning “puma” and Acolhua, the name of the ethnic group making up most of the Texcoco kingdom. So, this future king’s name literally meant “Puma of the Acolhua People.” In his later youth, Ahcolmiztli would change his name to Nezahualcoyotl. Many people have translated Nezahualcoyotl to mean “Hungry Coyote” or “Fasting Coyote.” Technically, both translations are incorrect. Nezahualcoyotl literally means, “Coyote Wearing a Fasting Collar.” In ancient central Mexico when people abstained from food in a formal fast, they would wear a collar made out of twisted bands of paper called a nezahualli so that everyone around them knew they were fasting. The name glyph of Nezahualcoyotl – what we might call a “royal cipher” in English – features a head of a coyote with the nezahualli fasting collar. So, “Hungry Coyote” is a little bit of a misnomer. Anyone who has been on a long-term fast can attest to the fact that after a few days of no food you just stop being hungry. So, anyone wearing the nezahualli was not necessarily “hungry.”

The royal family of the Kingdom of Texcoco was very happy to welcome the heir to the throne into their complex world. Nezahualcoyotl’s father was King Ixtilxoxitl the First whose reign was wracked by wars and other disputes with his neighbors. Like all kings throughout time, King Ixtilxoxitl sought a powerful alliance through marriage, and thus married Nezahualcoyotl’s mother, the Princess Matlalcihuatzin of Tenochtitlan, who was the daughter of Tenochtitlan’s king, Huitzilihuitl. So, the future king of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl, was therefore half Acolhua and half Mexica, or Aztec. The young prince had many advantages, but his parents raised him in a very austere way because Texcoco was always at a heightened state of alert. In 1409 when Nezahualcoyotl was seven years old his father Ixtilxoxitl became king of Texcoco. Tensions intensified within the first few years of his reign when King Ixtilxoxitl refused to continue to pay tribute to the Tepanec Empire whose capital, Azcapotzalco, was located on the western shores of Lake Texcoco. What amounted to extortion payments to a foreign ruler did not sit well with the father of the young Prince Nezahualcoyotl. King Ixtilxoxitl reached out to the king of Tenochtitlan for support and to broker a peace between the Tepanec Empire and Texcoco, but the king of Tenochtitlan refused because the royal family of that city had deeper ties through marriage with the Tepanecs. So, Nezahualcoyotl’s father either had to pay up or face the Tepanec Empire without any allies. Tezozomoc, the absolute ruler of the Tepanec Empire declared war against the Kingdom of Texcoco and gathered together an expeditionary force to invade Texcoco lands. Tezozomoc’s army did not only include warriors from the Tepanec Empire, but also included some Aztec or Mexica fighters given to the ruler by the king of Tenochtitlan. The Tepanec imperial army seemed like an overpowering force against Texcoco, but Nezahualcoyotl’s father was a brilliant military commander and pushed back the Tepanec forces. In fact, the Texcoco army even drove the Tepanec military back to their capital city of Azcapotzalco and laid siege to that city for several months but could not capture it. With no signs of the people of Azcapotzalco giving in, the Texcoco forces returned to their homeland. The entire time during this war, the young prince Nezahualcoyotl, who was a young teenager at the time, fought alongside his father and was valiant in battle. The war was not over with their retreat, however.

The royal family of the Kingdom of Texcoco was very happy to welcome the heir to the throne into their complex world. Nezahualcoyotl’s father was King Ixtilxoxitl the First whose reign was wracked by wars and other disputes with his neighbors. Like all kings throughout time, King Ixtilxoxitl sought a powerful alliance through marriage, and thus married Nezahualcoyotl’s mother, the Princess Matlalcihuatzin of Tenochtitlan, who was the daughter of Tenochtitlan’s king, Huitzilihuitl. So, the future king of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl, was therefore half Acolhua and half Mexica, or Aztec. The young prince had many advantages, but his parents raised him in a very austere way because Texcoco was always at a heightened state of alert. In 1409 when Nezahualcoyotl was seven years old his father Ixtilxoxitl became king of Texcoco. Tensions intensified within the first few years of his reign when King Ixtilxoxitl refused to continue to pay tribute to the Tepanec Empire whose capital, Azcapotzalco, was located on the western shores of Lake Texcoco. What amounted to extortion payments to a foreign ruler did not sit well with the father of the young Prince Nezahualcoyotl. King Ixtilxoxitl reached out to the king of Tenochtitlan for support and to broker a peace between the Tepanec Empire and Texcoco, but the king of Tenochtitlan refused because the royal family of that city had deeper ties through marriage with the Tepanecs. So, Nezahualcoyotl’s father either had to pay up or face the Tepanec Empire without any allies. Tezozomoc, the absolute ruler of the Tepanec Empire declared war against the Kingdom of Texcoco and gathered together an expeditionary force to invade Texcoco lands. Tezozomoc’s army did not only include warriors from the Tepanec Empire, but also included some Aztec or Mexica fighters given to the ruler by the king of Tenochtitlan. The Tepanec imperial army seemed like an overpowering force against Texcoco, but Nezahualcoyotl’s father was a brilliant military commander and pushed back the Tepanec forces. In fact, the Texcoco army even drove the Tepanec military back to their capital city of Azcapotzalco and laid siege to that city for several months but could not capture it. With no signs of the people of Azcapotzalco giving in, the Texcoco forces returned to their homeland. The entire time during this war, the young prince Nezahualcoyotl, who was a young teenager at the time, fought alongside his father and was valiant in battle. The war was not over with their retreat, however.

In early 1418, Emperor Tezozomoc of the Tepanecs regrouped and marched with a larger army into the Kingdom of Texcoco. The Tepanecs arrived at the capital city of Texcoco, eliminating all resistance along the way. The city of Texcoco soon fell and the Tepanecs executed most of the ruling elite class, but the young prince Nezahualcoyotl escaped with his father King Ixtilxoxitl and a handful of others, fleeing to the hills to the east. The Tepanecs were hot on their trail and when they were closing in, the king of Texcoco told his son Nezahualcoyotl to hide in a tree. The young prince did, and from that terrible vantage point he saw the capture and execution of his father. Nezahualcoyotl then became a fugitive with a bounty on his head. Emperor Tezozomoc of the Tepanecs wanted Nezahualcoyotl to be captured and brought to the Tepanec capital for a public execution. In the years on the run Nezahualcoyotl pretended to be a commoner and joined the army of the small Kingdom of Huexotzinco to the east – near modern-day Puebla – where he honed his military skills and planned for his return to Texcoco. Remember, Nezahualcoyotl was half Aztec and his mother was part of the ruling family of Tenochtitlan. His aunts arranged for his return to central Mexico, paying bribes to allow him safe passage disguised as an Aztec merchant. Soon after Nezahualcoyotl arrived in the Aztec capital, the old emperor of the Tepanecs, Tezozomoc, died and was succeeded by his son, Maxtla, who said he would allow Nezahualcoyotl to return to Texcoco under certain conditions. When Nezahualcoyotl found out that the new Tepanec emperor was plotting to kill him, he went into exile again.

In early 1418, Emperor Tezozomoc of the Tepanecs regrouped and marched with a larger army into the Kingdom of Texcoco. The Tepanecs arrived at the capital city of Texcoco, eliminating all resistance along the way. The city of Texcoco soon fell and the Tepanecs executed most of the ruling elite class, but the young prince Nezahualcoyotl escaped with his father King Ixtilxoxitl and a handful of others, fleeing to the hills to the east. The Tepanecs were hot on their trail and when they were closing in, the king of Texcoco told his son Nezahualcoyotl to hide in a tree. The young prince did, and from that terrible vantage point he saw the capture and execution of his father. Nezahualcoyotl then became a fugitive with a bounty on his head. Emperor Tezozomoc of the Tepanecs wanted Nezahualcoyotl to be captured and brought to the Tepanec capital for a public execution. In the years on the run Nezahualcoyotl pretended to be a commoner and joined the army of the small Kingdom of Huexotzinco to the east – near modern-day Puebla – where he honed his military skills and planned for his return to Texcoco. Remember, Nezahualcoyotl was half Aztec and his mother was part of the ruling family of Tenochtitlan. His aunts arranged for his return to central Mexico, paying bribes to allow him safe passage disguised as an Aztec merchant. Soon after Nezahualcoyotl arrived in the Aztec capital, the old emperor of the Tepanecs, Tezozomoc, died and was succeeded by his son, Maxtla, who said he would allow Nezahualcoyotl to return to Texcoco under certain conditions. When Nezahualcoyotl found out that the new Tepanec emperor was plotting to kill him, he went into exile again.

When in his second exile, Nezahualcoyotl felt even more determined to regain his kingdom. The new king of Tenochtitlan, Itzcoatl, was tired of having the Tepanecs as his bad neighbors and was more sympathetic to Nezahualcoyotl’s cause than his father had been. With some help from Itzcoatl, Nezahualcoyotl raised an army from various political entities throughout the Valley of Mexico and even recruited men who knew him in the faraway Kingdom of Huexotzinco where he once served in their army. Nezahualcoyotl managed to unite the peoples of Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Tlacopan, Tlaxcala, Chalco and Huexotzinco into one fighting force to take care of the Tepanec situation once and for all. The army of nearly 100,000 men under the leadership of Nezahualcoyotl was victorious and captured the Tepanec capital of Azcapotzalco with ease. Most of the peoples of central Mexico had been united against a common enemy for the very first time. Nezahualcoyotl returned to Texcoco as king. The kingdom became part of what was later called the Triple Alliance which would eventually evolve into the Aztec Empire.

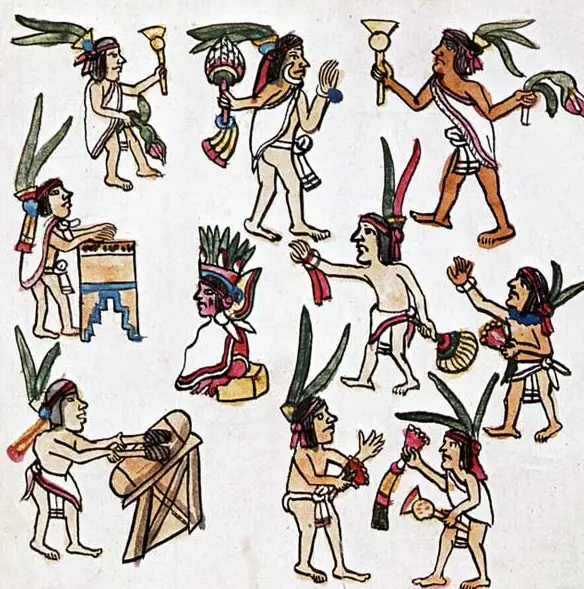

Nezahualcoyotl ruled Texcoco from 1429 to his death in 1472, a period of almost 43 years. In the early years of his reign, he sought to reestablish order in the Kingdom of Texcoco, adopting the legal system of the Mexica that he had learned about while staying in Teochtitlan. Texcoco had always been a wealthy kingdom and the money flowing into the capital city helped fund public works projects, including a massive system of dikes that separated the brackish waters from the fresh waters of Lake Texcoco. History records this dike system as being designed by Nezahualcoyotl himself. In addition to the dikes, the capital city had an extensive and elaborate aqueduct system. Visitors marveled at Texcoco’s beautiful palaces and temples, its exquisite public sculptures, and magnificent flowering gardens. As the central valleys of Mexico were at peace for the first time in centuries, the Kingdom of Texcoco flourished as a center of art and culture. Some historians refer to Texcoco as “The Athens of the New World.” As a promoter of the arts, Nezahualcoyotl established ancient Mexico’s largest library, often compared to the Library of Alexandria, that included codices and other books and manuscripts from all over Mesoamerica. The library was said to contain thousands of documents from various cultures and time periods, but after the Spanish Conquest there was nothing written about it, and no one knows where the contents of that library ended up. Nezahualcoyotl also founded the Texcoco Academy of Music which invited musicians from all over Mesoamerica to attend. Qualified students came from as far away as the Maya areas some 700 miles away to study there. At court, King Nezahualcoyotl cultivated an elite class of artists, scholars, musicians and poets known collectively as the tlamatini. At this time, during the rule of Nezahualcoyotl, Texcoco set the cultural standard for other ancient Mexican cities and kingdoms to aspire to.

Nezahualcoyotl ruled Texcoco from 1429 to his death in 1472, a period of almost 43 years. In the early years of his reign, he sought to reestablish order in the Kingdom of Texcoco, adopting the legal system of the Mexica that he had learned about while staying in Teochtitlan. Texcoco had always been a wealthy kingdom and the money flowing into the capital city helped fund public works projects, including a massive system of dikes that separated the brackish waters from the fresh waters of Lake Texcoco. History records this dike system as being designed by Nezahualcoyotl himself. In addition to the dikes, the capital city had an extensive and elaborate aqueduct system. Visitors marveled at Texcoco’s beautiful palaces and temples, its exquisite public sculptures, and magnificent flowering gardens. As the central valleys of Mexico were at peace for the first time in centuries, the Kingdom of Texcoco flourished as a center of art and culture. Some historians refer to Texcoco as “The Athens of the New World.” As a promoter of the arts, Nezahualcoyotl established ancient Mexico’s largest library, often compared to the Library of Alexandria, that included codices and other books and manuscripts from all over Mesoamerica. The library was said to contain thousands of documents from various cultures and time periods, but after the Spanish Conquest there was nothing written about it, and no one knows where the contents of that library ended up. Nezahualcoyotl also founded the Texcoco Academy of Music which invited musicians from all over Mesoamerica to attend. Qualified students came from as far away as the Maya areas some 700 miles away to study there. At court, King Nezahualcoyotl cultivated an elite class of artists, scholars, musicians and poets known collectively as the tlamatini. At this time, during the rule of Nezahualcoyotl, Texcoco set the cultural standard for other ancient Mexican cities and kingdoms to aspire to.

In addition to designing and personally supervising the building projects in his kingdom, Nezahualcoyotl is best known for his poetry. He created many poems in Classical Nahuatl that were recited by bards at public festivals and events. These poems survived through the oral tradition until they were written down in the late 1500s and early 1600s by some of Nezahualcoyotl’s descendants. Notable among them were Fernando Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl and Juan Bautista Pomar. Some of Nezahualcoyotl’s poems include “Song of Springtime,” “He, Alone,” “I am Sad,” “I am Wealthy,” “Be Joyful,” and “The Struggle.”

Nezahualcoyotl was said to have fathered over 140 children with various wives and concubines. At the age of 62 he and his primary wife had a child called Nezahualpilli who would be his designated successor and the second-to-last true king of Texcoco. Nezahualcoyotl passed away peacefully at the royal palace of Texcoco on June 4, 1472. He left behind a legacy unmatched among the rulers of ancient Mexico and his impact on ancient Mesoamerican art and culture cannot be adequately assessed.

For more about the royal dynasty of Texcoco, please see this Mexico Unexplained episode: https://mexicounexplained.com/the-tragic-history-of-the-house-of-texcoco/

REFERENCES

Bowles, David. “Kings and Queens of Texcoco” Medium.com, 12 Aug 2019.

Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961.