Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

On May 17, 1853, California governor John Bigler signed a bill into law to deal with an increase in lawlessness caused by Mexican bandits throughout the new American state. The law stated that the war veteran Captain Harry Love, would assemble a team of no more than 20 men to be called the California Rangers to be paid $150 a month for no more than 3 months, to “capture, drive out of the country, or exterminate the desperate bands of highwaymen who placed in continual jeopardy both life and property.” The law was written with one specific person in mind, a notorious Mexican bandit named Joaquín Murrieta who had terrorized the California countryside since the first years of the gold rush. Many bounties had been placed on Murrieta’s head by various individuals and elements of law enforcement, but this 1853 law passed at a state level was serious business. Joaquín Murrieta was the stuff of legend, both during and after his life. He was feared and admired, and became one of the most controversial figures of northern Mexico and the new American West. This is his story.

On May 17, 1853, California governor John Bigler signed a bill into law to deal with an increase in lawlessness caused by Mexican bandits throughout the new American state. The law stated that the war veteran Captain Harry Love, would assemble a team of no more than 20 men to be called the California Rangers to be paid $150 a month for no more than 3 months, to “capture, drive out of the country, or exterminate the desperate bands of highwaymen who placed in continual jeopardy both life and property.” The law was written with one specific person in mind, a notorious Mexican bandit named Joaquín Murrieta who had terrorized the California countryside since the first years of the gold rush. Many bounties had been placed on Murrieta’s head by various individuals and elements of law enforcement, but this 1853 law passed at a state level was serious business. Joaquín Murrieta was the stuff of legend, both during and after his life. He was feared and admired, and became one of the most controversial figures of northern Mexico and the new American West. This is his story.

The confusion of the details of the life of Joaquín Murrieta begins with his birth. Some sources claim he was born in Hermosillo, the capital of the northern Mexican state of Sonora. Some researchers believe that he was born on a small rancho outside the town of Tapizuelas which is located in southern Sonora just north of the border with Sinaloa. There are many people with the last name Murrieta who still live in that area today who claim kinship with the legendary bandit. Still other sources cite that Joaquín Murrieta was born outside the north-central Sonoran town of Trincheras which is the site of a mysterious and expansive lost city described in Mexico Unexplained episode number 297: https://mexicounexplained.com/cerro-de-trincheras-lost-city-of-the-sonoran-desert/ And still other, vaguer sources claim that the famous bandit was born in California when it was still part of Mexico. Most researchers agree that Murrieta was born in either 1829 or 1830, nearly 20 years before the United States took over what is now known as the American Southwest. Some sources claim that Murrieta was from, “a respectable family,” but as this last name is common in Sonora and the exact names of Joaquín’s parents are not known, it is hard to make any firm conclusions about his parentage or deeper ancestry.

Murrieta appears in the history books again during the California Gold Rush of 1849. The US had recently acquired California in the Mexican War and the border as we know it today was very fluid and almost an afterthought back in Murrieta’s day. Joaquín and a small group from his town made the journey to the California gold fields after they had received word that Joaquín’s stepbrother who was also named Joaquín – specifically, Joaquín Manuel Carrillo Murrieta – had enjoyed great success in the mining camps. Among the small band crossing the harsh Altar Desert from Sonora was Joaquín’s young wife, Rosa Feliz. In some stories they are not married. In any event, when they got to California, the Murrieta party did not have the best of luck even though Joaquín and his group did manage to stake a claim and find gold.

Murrieta appears in the history books again during the California Gold Rush of 1849. The US had recently acquired California in the Mexican War and the border as we know it today was very fluid and almost an afterthought back in Murrieta’s day. Joaquín and a small group from his town made the journey to the California gold fields after they had received word that Joaquín’s stepbrother who was also named Joaquín – specifically, Joaquín Manuel Carrillo Murrieta – had enjoyed great success in the mining camps. Among the small band crossing the harsh Altar Desert from Sonora was Joaquín’s young wife, Rosa Feliz. In some stories they are not married. In any event, when they got to California, the Murrieta party did not have the best of luck even though Joaquín and his group did manage to stake a claim and find gold.

Conflicting stories abound regarding what happened next. Some say that American miners were jealous of Murrieta’s success, so they beat him up after tying him to a chair and made him watch as they tortured and killed his wife. In another story, Joaquín Murrieta and his older half brother were accused of stealing horses by the Americans and in this version his brother was killed by an angry mob along with Rosa Feliz, and Joaquín was badly beaten. In historical records of the fledgling state of California, there is a legal action against a man named Joaquín Murrieta who was accused of being a horse thief, but the other details of what happened to his brother and his wife Rosa Feliz cannot be found in any official written history at the time. In any case, the events that happened after Joaquín arrived in California and had moderate success in gold mining led Murrieta to the life of lawlessness, seeking revenge against those who harmed and killed members of his family. According to historian Frank Latta, in his 1980 book, Joaquín Murrieta and His Horse Gangs, Murrieta put together a large gang organized into smaller bands headed by close friends and family members. The gang had two purposes: to exact revenge on the people who killed or hurt Murrieta’s family and friends, and to engage in an illegal cross-border horse trade. The gang would steal horses from the American side and transport them across the Mexican border along with wild mustangs that were illegally rounded up. Murrieta’s business of rounding up mustangs was technically illegal because the new state of California extracted a tax for each mustang gathered from the wild. In the press and even in official government documents, the gang was referred to as The Gang of the Five Joaquíns. The leaders included Joaquín Ocomorenia, Joaquín Valenzuela, Joaquín Botellier, Joaquín Carrillo, and of course, Joaquín Murrieta. In the 1853 legislation mentioned earlier, Murrieta was erroneously referred to as “Joaquín Muriati.”

The gang accomplished what it set out to do and killed most of the people who originally wronged Joaquín Murrieta and beyond. During the early days of the state of California, especially in the mining camps, there was a lot of prejudice and discrimination against Mexicans, especially those who became successful. Although property owned by Mexicans who had been in California before it became part of the United States was technically protected by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, many Mexicans were pushed off their lands by Anglo-American settlers, and there were many injustices committed against Mexican people in California at the time. These many injustices fueled Joaquín Murrieta’s folk hero status among the Mexican people who saw him and his men as vehicles to right the wrongs that they had seen and experienced. Within a short period of time – only a few years – the gangs Murrieta started had been a source of grave concern to the newly formed American political structure of California. This is why there had to be a law that specifically mentioned Murrieta and his men in order to put an end to this supposed menace. Many Mexicans, who felt powerless under the new regime, cheered on and even assisted Murrieta in his many exploits.

The gang accomplished what it set out to do and killed most of the people who originally wronged Joaquín Murrieta and beyond. During the early days of the state of California, especially in the mining camps, there was a lot of prejudice and discrimination against Mexicans, especially those who became successful. Although property owned by Mexicans who had been in California before it became part of the United States was technically protected by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, many Mexicans were pushed off their lands by Anglo-American settlers, and there were many injustices committed against Mexican people in California at the time. These many injustices fueled Joaquín Murrieta’s folk hero status among the Mexican people who saw him and his men as vehicles to right the wrongs that they had seen and experienced. Within a short period of time – only a few years – the gangs Murrieta started had been a source of grave concern to the newly formed American political structure of California. This is why there had to be a law that specifically mentioned Murrieta and his men in order to put an end to this supposed menace. Many Mexicans, who felt powerless under the new regime, cheered on and even assisted Murrieta in his many exploits.

There is an important sidebar to mention here that often gets overlooked by historians and other researchers. Although the banditry the Five Joaquíns Gang engaged in never touched the lives of Mexicans in a negative way, it was not restricted to whites. The gang also attacked Chinese mining camps, killing and stealing. In fact, the final tally of killings, based on official accounts taken in 1853, included a total of 13 Anglo-Americans and 28 Chinese. The Joaquíns, therefore, killed twice as many Chinese as whites.

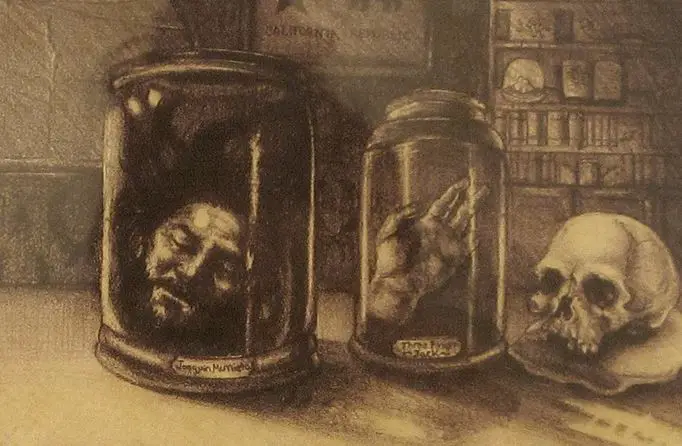

The formation of the California Rangers would put an end to this bandit problem. Mexican War veteran and the head of the Rangers, Captain Harry Love, eventually took care of the situation, or did he? According to a mixture of facts and questionable tall tales, on July 25, 1853, Captain Love and a group of Rangers encountered a group of armed Mexican horsemen outside the town of Coalinga in modern-day Fresno County. After a brief shoot-out, three Mexicans were killed. Among them was supposedly Joaquín Murrieta, and another was a man named Manuel García, also known in the mining camps as “Three-Fingered Jack.” This is where the story becomes a bit murky. Although there were some popular illustrations of Joaquín Murrieta in the press at the time, no one knew what he really looked like, and that included Captain Love. The Rangers were sure that they had killed García, aka Three-Fingered Jack, but some researchers believe that Joaquín Murrieta did not really die that hot July day in 1853. Captain Love cut off the head of the alleged Murrieta and severed the hand from the dead García and put them in jars of alcohol to prove that the outlaws had been killed. This evidence was enough for Love and the Rangers to collect the bounty on the bandits and to bask in the glory of ridding California of the Murrieta scourge. The jars would later be paraded throughout California and for $1.00 spectators from San Francisco to Los Angeles could gawk at the relics. Some at the time claimed that Love and the Rangers happened upon a group of innocent mustang wranglers and killed some of them later bribing witnesses to give false testimony just to get the reward money. A month after the murders a letter appeared in the San Francisco Alta California Daily from an anonymous man from Los Angeles trying to expose Love’s fakery and fraud. In 1854, the California legislature ignored all counter claims to the  authenticity of the killings and awarded the California Rangers an additional $5,000 for what was hailed as the end of Mexican banditry in California. Doubts persisted, though, and some 25 years later, Joaquín Murrieta’s sister came forward and said that the head in the jar that was paraded throughout California was not the head of her brother. Others spoke up at the time and claimed to have seen Murrieta alive, both in California and across the border either in Baja or in his native Sonora. Not a single sighting had ever been verified. What about possible DNA tests to be done on the head in the jar and comparing the results with those of close relatives? The jar with Murrieta’s supposed head in it was destroyed during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire. Many researchers have tried to track the trail of Murrieta after the supposed execution by Captain Love and the Califotnia Rangers, but no one has been successful in doing so. This may prove as difficult as verifying many of the details of the bandit’s life, which have been embellished and added to over time and have taken on lives of their own.

authenticity of the killings and awarded the California Rangers an additional $5,000 for what was hailed as the end of Mexican banditry in California. Doubts persisted, though, and some 25 years later, Joaquín Murrieta’s sister came forward and said that the head in the jar that was paraded throughout California was not the head of her brother. Others spoke up at the time and claimed to have seen Murrieta alive, both in California and across the border either in Baja or in his native Sonora. Not a single sighting had ever been verified. What about possible DNA tests to be done on the head in the jar and comparing the results with those of close relatives? The jar with Murrieta’s supposed head in it was destroyed during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fire. Many researchers have tried to track the trail of Murrieta after the supposed execution by Captain Love and the Califotnia Rangers, but no one has been successful in doing so. This may prove as difficult as verifying many of the details of the bandit’s life, which have been embellished and added to over time and have taken on lives of their own.

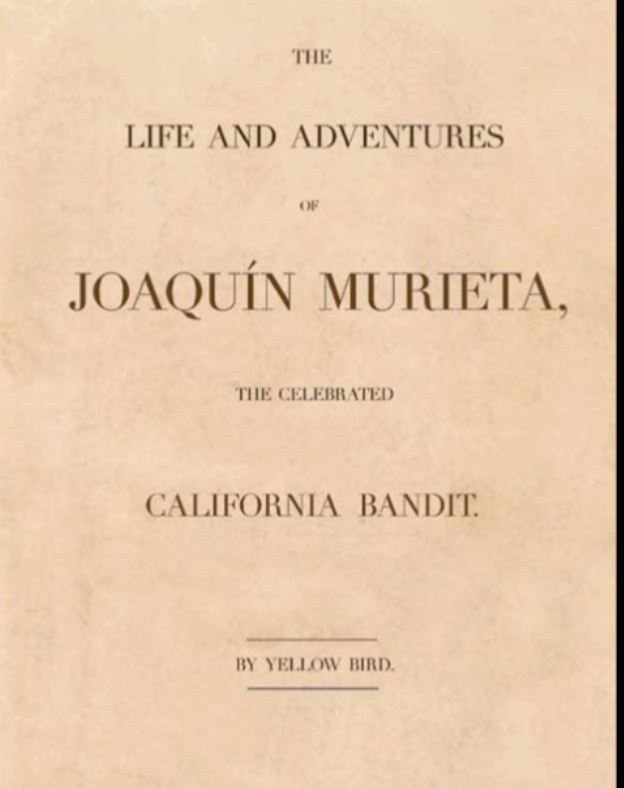

The biggest source of information that historians have to draw on regarding the life and times of Joaquín Murrieta is a book published in 1854, the year of his death. The book was titled The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit. The book deserves some brief mentioning because of how important it was. It is considered a work of historical fiction and mixes verifiable facts with legends and is presented in the form of a novel. It was written by a man named John Rollin Ridge who wrote the book under the pen name Yellow Bird. Born with the name Chees-quat-a-law-ny in 1827, Ridge was Cherokee. The book, therefore, is the first novel ever to be written by a Native American and also the first novel ever to be written in California under American occupation. Among the legendary elements and elaborations which were also seen in the popular press at the time, there are numerous important facts in this book that historians continue to use to aid in their research on the enigmatic figure of Joaquín Murrieta. Ridge’s book also set the stage for a throng of short stories and magazine articles that spanned from coast to coast and across many decades fueling the imagination of the lawlessness of the Wild West. Some believe that that character of Zorro was based on Murrieta. Popular culture scholars make the case that Murrieta-Zorro later evolved into the Lone Ranger and then Batman, taking elements of the Joaquín Murrieta story well into the 21st Century. Murrieta and derivations of him are still seen in stories, comics, songs, Japanese anime and online blogs. He has become an enduring folk hero and fighter for justice among certain elements of the modern-day Mexican American community. While the fact that Murrieta died at the hands of the California Rangers in July of 1853 may be in dispute, there is no doubt that his legend lives on.

REFERENCES

Mariotte, Jeffrey J. and Peter Murrieta. Blood and Gold: The Legend of Joaquín Murrieta. Tucson: Sundown Press, 2021. We are Amazon affiliates. Order the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3t2Ji73

Ridge, John Rollin. The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit. New York: Penguin Classics, 2018. We are Amazon affiliates. Order the book on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/3DEHWnR

2 thoughts on “Joaquín Murrieta, Legendary Mexican Bandit”

Robert, these podcasts are really high quality and very interesting. Surprised more people don’t comment. Can you do a long version for each subject group so they will play one after another without bed to keep selecting the next podcast . Thanks Adam

Hi Adam, Thanks for your comments and your interest. I am not sure how to go about stringing the podcasts together like that in this format. I am also surprised more people don’t comment, but I am even more surprised that after over 7 years of weekly shows I have so little to show for it all.